Last year, the NIH announced that at the direction of Congress, the organization would tighten rules for reporting sexual and workplace harassment by investigators funded by the NIH.

This was seen as a step in the right direction—to try to close the loopholes that have contributed to the ability of these types of perpetrators to continue in their careers and advance with no repercussions.

These new rules are meant to stop the pervasive culture of “failing up” and “pass the harasser” that has perpetuated within health care and academia for years. The hierarchal structure and male-dominated leadership in academic medicine can contribute to an environment more conducive to sexual harassment.

Academic medicine has the highest incidence of gender and sexual harassment, compared to other scientific fields with 30-70% of female physicians, and as many as 50% of medical students reporting being sexually harassed.

By implementing DARVO—an acronym for deny, attack, and reverse victim and offender—falling back on hierarchal traditions, citing the “old boys club” or discounting behavior as “locker room talk,” it often feels like accountability for acts of harassment, sexual or otherwise, is a pipe dream.

Time and time again, we have seen male leaders “fail up” after sexual harassment comes to light, and the victims are often left with a scarlet letter that unfortunately results in the demise of many promising careers.

When the banner is raised and accountability is called for, it is often the women who have been harassed calling for justice, and, unfortunately, justice is not often served. These new NIH rules were meant to prevent this from happening.

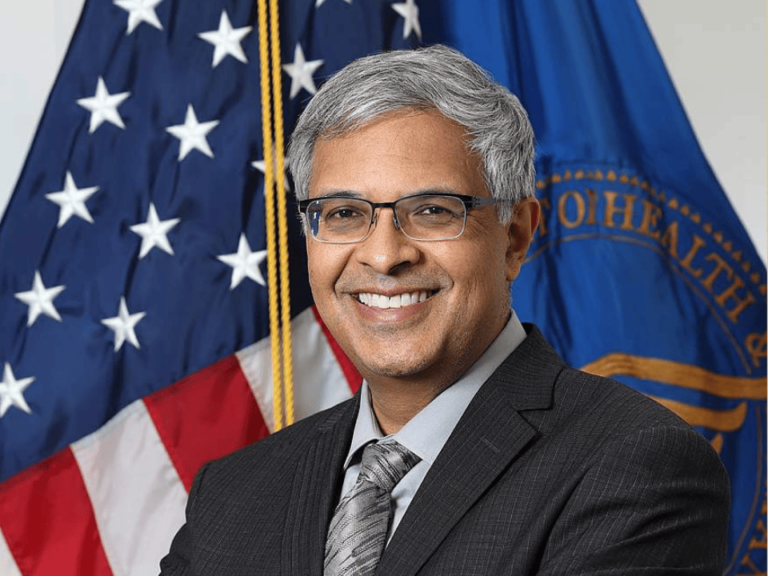

It was predicted that this policy may not be as effective and did not go as far as it needed to in order to move towards real culture change, and unfortunately it seems that prediction thus far is coming true. It does not seem the policies have had the needed impact, and it may be up to potential incoming NIH Director Dr. Monica Bertagnolli to revisit and retool the new rules to make the policy and interventions more impactful.

Some concerns that were brought up early on included that the NIH would need to go further to hold individuals and organizations accountable. Case in point: The high-profile case of David Gilbert, a researcher awarded $2.5 million in grants who transferred institutions while a sexual harassment investigation was ongoing. None of this deterred Gilbert from continuing on in his well-funded career, despite the allegations eventually being proven to be true. This was taking place during the time the NIH claimed to be further cracking down on these issues.

In 2022, when Congress wrote a tightened policy into law making it mandatory for institutions to inform the NIH of disciplinary action taken against harassers regardless of whether this resulted in transferring a grant between institutions, Gilbert was not one of those named or impacted (The Cancer Letter, May 19, 2023).

In many cases, the severity of violations does not line up with an appropriate level of disciplinary actions undertaken by the individual institutions.

And if significant enough disciplinary actions are not undertaken, these harassers continue to harass, and grow their careers, with a slap on the wrist and no repercussions undertaken from the NIH, or any other regulatory body.

The pervasive culture of academia is often to protect the harasser, especially if the individual is largely grant funded, a big name, or has power. By bullying the accuser, silencing supporters, and minimizing the impact of the harassment, these types of predators continue to wreak endless havoc on the careers of others, and contribute to a toxic work environment.

Ask most women in academic medicine and they will be able to name multiple examples they have personally experienced of harassment that was never addressed. Many times, those who are the victims of this type of behavior feel powerless, and a recent incident that occurred at a national ACOG conference depicts the long-lasting impact this type of abuse can have on not only the victim, but also on family members.

If the NIH wants to have a meaningful impact and not only address workplace harassment, but also work towards culture change so this behavior is not only not tolerated, but it is appropriately dealt with, there are many more steps that needed to be undertaken.

Simply, transparency is key, and reinforcing policies across the board, with substantive actions taken to address workplace harassment and discrimination are necessary.

Follow-up and continuous evaluation of the organization and policies in place, as well as regular surveys to employees to ensure of a culture of harassment is not the norm, and then acting on the results of these surveys, would be necessary.

Ensuring accountability and making employees feel comfortable reporting incidents, with no fear of repercussions is necessary to ensure these types of perpetrators do not simply move to other institutions and continue their bad behavior.

If appointed, Dr. Monica Bertagnolli has an opportunity as the next NIH director to foster a culture of transparency and true accountability for these types of behaviors. Repercussions are often necessary even if the institution at which the individual works does not deem a leave of absence necessary or an appropriate punishment.

The NIH should require institutions to inform the agency when a harassment investigation begins, and provide the information uncovered by such investigations. The penalty and outcome of these investigations should be reviewed by a committee external to the organization in order to have an objective decision and outcomes.

The #MeToo movement has made it clear that, for too long, organizations have been willing to overlook bad behavior if the individual continues to be an effective contributor to the institution, whether financially, through grant funding, accolades and awards, or in other ways. Unfortunately, that incentivizes organizations to overlook bad behavior and instead implement ineffective reprimands that are not commensurate with the acts.

As proposed by Dr. Esther Choo and colleagues, organizations should use standardized and validated instruments to annually and anonymously survey their employees. Survey data should then be reported throughout the organization, with strategies then implemented on how to improve. Not only are secure methods for reporting harassment needed, but follow-through is imperative.

When harassment is brought to light, there must be real consequences if the investigation concludes that harassment has indeed occurred. And these types of interventions, when initiated, should be reported to the NIH so they can follow along with the institution, and ensure bad actors are not continually rewarded when their misbehavior is downplayed by the institution.

Those who have been harassed will only come forward if they feel not only that they will be protected, but also that in bringing these issues to light, there will be real consequences for the perpetrator. Individuals must no longer be allowed to “fail up” or be offered an option for quiet retirement or reassignment elsewhere.

To be sure, all those accused are innocent until proven guilty, and due process is necessary when these investigations are undertaken. But until a process exists where institutions and individuals can be held accountable for delivering punishments that fit the crimes, the policy and decisions must be handled by those independent from the organization if we want true justice to be served.

If appointed, Dr. Bertagnolli has an opportunity to pioneer a true culture shift in academia, with accountability for bad actors, and protection and support for victims.

We all hope she is up to the challenge.