On Dec. 21, 1973, Jerry D. Boyd ran the first printing of a little newsletter that would become The Cancer Letter.

Today, 50 years later, those eight pages brimming with stories of oncopolitics, research funding, appointments, and NCAB recommendations seem remarkably familiar. Just look at our most-read stories of 2023: the names have changed, but the overarching themes have not (The Cancer Letter, Dec. 15, 2023).

La plus ça change, la plus c’est la même chose. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

When Jerry retired in 1990, he joked that there’d be no job at The Cancer Letter for a new generation—if only because he believed that cancer itself could be a relic of history. He would have been delighted to close up shop upon receiving news that cancer was, as they used to say, “solved.”

Jerry was as enthusiastic as he was impatient: “Chuck, don’t give this statistical significance crap, just tell me whether it works,” he once said to Charles Moertel, the Mayo Clinic expert in colorectal cancer, a proponent of rigorous clinical trials, and a member and chairman of the FDA Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee.

Jerry died Sept. 24, 2019, at 91 (The Cancer Letter, Sept. 27, 2019).

Jerry would find it remarkable that The Cancer Letter, his big idea on eight little pages, has now documented half a century of cancer progress—something he called “the story of the century.” And some of those stories have gone straight into the history books.

Over the course of our 50th anniversary year, we’ll be looking back at how much the field has (and hasn’t) changed, the stories we’ve told, and the impact The Cancer Letter has had.

A community in need of a paper

Following the signing of the National Cancer Act of 1971, Jerry, who had been covering NCI for the Blue Sheet, a now defunct policy newsletter focused on health care, saw that the emerging cancer community needed a community newspaper.

As a former sports writer who had previously run a community newspaper in California, Jerry had keen news judgment, a sense of local politics, and a knack for keeping score.

To me, a journalist, the progress in cancer survival and in understanding human biology during the last 20 years has seemed to be the story of the century.

Jerry Boyd

“I talked to the publisher and said that I think we ought to devote a section of the Blue Sheet just to NCI and play down some of these other institutes that aren’t getting much money,” Jerry said in an oral history shortly before his death. “And he thought about it and he said, ‘I don’t think we will. I don’t think there’s enough money in there to support, or potential money in subscriptions, to support that kind of a dedication which would be the space plus at least one salary.’

“I said that I thought that maybe I might try it myself.”

He did just that. And with a stack of printed up sample issues, he walked into a January 1974 National Cancer Advisory Board meeting and walked out with his first check.

The check—for $100—was from John Ultmann, then director of the University of Chicago Cancer Research Center.

“I didn’t do any market research amounting to anything. The only marketing that I really did for The Cancer Letter is to take the first issue to one of the NCAB meetings,” Jerry said.

However, he also mailed the first two issues out as samples to AACR members.

Reflecting on that first issue in 2019, Jerry speculated that his reporting had a role in the 1974 renewal of the National Cancer Act:

The very first story was that the Secretary of Health under Nixon was still a little burnt up about being overridden on that $100 million extra money. He told me that he was going to oppose renewing that National Cancer Act of 1971.

It only had one year authorization, and he was going to oppose renewing it, so I put that as the lead story in that sample issue.

Now, I wouldn’t swear to it, it was that issue or the real first issue, but it was right in there, and people got excited about that. All this stuff had just gotten started, and they’re going to lose their support for it. No way.

Here comes a load of mail again. It wasn’t nearly as many as Ann Landers would produce, but we didn’t need to bring her out on it again, because just our subscriber list… Well, they weren’t subscribers yet, but our mailing list got back and responded enough to it that they convinced the secretary to back off, and Ted Kennedy got into it and started haggling away and the National Cancer Act had no problem getting renewed.

Now, that’s when we realized we had enough subscriptions to begin with.

Jerry’s timing couldn’t have been better: A nascent field, exploding with activity and promise, finds itself on the brink of losing everything. But, now, when most newsletters have disappeared, it’s clear that Jerry brought something special to the table.

The first issue has now been fully digitized, and The Cancer Letter’s full archive, from 1973 through today, provides a week-by-week history of how oncology got where it is today.

That first issue didn’t get many subscribers, Jerry’s wife and business partner, Julie, said to The Cancer Letter. “But then we put out a second issue and subscriptions just rolled in. Jerry was right, researchers were eager to get that access.”

She encouraged Jerry to take the risk.

“Jerry was thinking about getting a side job and running The Cancer Letter in the evenings,” she said. “And I said, ‘No, Jerry, you don’t do well working for somebody else. You need to be your own boss.’ We were a team that way—we helped each other.”

By 1975, Jerry said, “we got a very high renewal rate. They started coming in pretty good numbers, too. It wasn’t long until we had over a thousand.”

From 8 pages to 70

Four decades ago, it was possible to delineate the clinical news from the political. Today, this line is porous. This convergence of two oncologies driven by patient expectations, increasing complexity and expense of novel therapies, Big Data, emergence of immunologic and precision therapies, and increasing reliance on biomarkers. It’s all one big story of systemic change, and The Cancer Letter has been on top of it.

Paul Goldberg

As Jerry read the National Cancer Act of 1971, he recognized that this new law would permanently change the way oncology consumed information.

“There was a lot of controversy about the targeted research vs. investigators presenting their own ideas,” Julie said. “There was an opening for someone to get that information to the researchers.”

As experienced newspaper entrepreneurs, the Boyds knew what it would take to publish a newspaper, and they decided against it. Newspapers required a lot of equipment, Julie said. “But with the newsletter, all you needed was a typewriter, basically.”

Entire industries needed to get news from Washington quickly and efficiently, and, without the internet, how else would you learn about RFPs, the latest rules and regs, and news tidbits on hirings and firings—inside the beltway and out? Newsletters provided a solution—and as soon as the internet came in, almost all of them went away.

Strictly speaking, The Cancer Letter has not been a newsletter since the 1990s. For one, we became an investigative news publication. Investigations, we have learned, rarely lend themselves to an 8-page format.

The Cancer Letter’s 8-page issues arose out of limitations of the printing process. Today, we have no such limitations, and can sometimes exceed 60 pages. The most recent issue was 70 pages long.

Hearing that number, Julie joked, “Jerry would probably say ‘Paul talks too much,’” referring to Paul Goldberg, editor and publisher of The Cancer Letter since 2011. “But you’re getting in more opinions and articles by other people that we didn’t do. Paul has expanded the scope of the newsletter.”

The Boyds retired in 1990, passing the publication to their daughter, Kirsten Boyd Goldberg, who served as editor and publisher until 2010 (The Cancer Letter, Jan. 7, 2011).

“Keeping up with the technology is what has kept The Cancer Letter relevant all these years,” Julie said. In 50 years, The Cancer Letter has evolved into a digital-first magazine.

In 1992, the same year the first commercial dial-up modem was released, The Cancer Letter launched its first website. By 1998, issues became available for download online. By 2008, the print edition had been eliminated entirely.

The content has evolved as well. “Journalism is not about compilation of fact. It’s about understanding what really matters,” Paul Goldberg wrote in an editorial in 2018. “It’s also about convening—understanding what people are arguing about, and making those arguments more informed, more spirited.

“Four decades ago, it was possible to delineate the clinical news from the political. Today, this line is porous. This convergence of two oncologies driven by patient expectations, increasing complexity and expense of novel therapies, Big Data, emergence of immunologic and precision therapies, and increasing reliance on biomarkers. It’s all one big story of systemic change, and The Cancer Letter has been on top of it.”

The story of the century

At the time of the signing of the National Cancer Act, the specialty of clinical oncology didn’t exist. The “C word” was usually a prequel to the “D word.” Death.

Some doctors, hematologists mostly, treated cancer, and in 1964 these dreamers formed the American Society of Clinical Oncology. These were seven “chemotherapists” having lunch in a small room at the Edgewater Beach Hotel in Chicago (The Cancer Letter, June 3, 2022). Board certification for oncologists wouldn’t begin until 1973. The phases of clinical research—phase I (dose finding), II (biological activity) and III (efficacy)—would emerge in the seventies.

Today, in the clinic, an oncologist may encounter a 12-year survivor of metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer, a disease that a decade ago killed its victims within seven to nine months.

“To me, a journalist, the progress in cancer survival and in understanding human biology during the last 20 years has seemed to be the story of the century,” Jerry wrote in a 1991 editorial commemorating the 20th anniversary of the National Cancer Act.

In the 50 years since that first issue, The Cancer Letter has had a unique role in the field, and recapping it is akin to writing a history book. What follows is a short history of oncology, as seen in real time through The Cancer Letter’s headlines:

Definitions, debates, and delineations

Source: Lasker Foundation

When the young field was building new definitions and ethical constructs, The Cancer Letter was there. Names like Gordon Zubrod, Emil Frei, J Freireich, Frank Rauscher, Charles Moertel, and other giants duked it out on the pages of each issue.

If some of these arguments sound familiar, it’s because many of the issues they address are ongoing. In oncology, debate over fundamental structures is eternal. Here are some early highlights:

- Zinder Report Asks VCP To Switch Most Research To Grants, Spread Work Among More Scientists, Change Review Groups, March 22, 1974 (Viral oncology archive)

- AACR, ASCO Members Concerned Over Ethics, Social Issues, And What To Do About Them, May 16, 1975

- When Is A Cancer Cured? NCI Suggest One-Year Survival Rates Useful In Determining Advances, Aug. 1, 1975

- Historical Vs. Current Controls: Comparability, Ethical Issues Argued By Moertel, Freireich, April 20, 1979

- “Great Charlie Moertel Shootout” In Tucson Draws Laughs, Criticism, April 17, 1981

- NCI Intramural Budget: Well-Funded Labs, High Costs, Or Deceiving Appearances?, April 21, 1994

Source: NCI

In 1980, Vincent T. DeVita, Jr. became the NCI director. In this role, he provided stable leadership and imposed a consistent vision on the nascent institute over the ensuing eight years. This vision included advancing treatment—as well as laying the groundwork for evidence-based cancer prevention:

- Fisher, Bonadonna Studies Still Fuel DeVita’s Optimism; Carbon Lists Six Basic Research Needs, July 15, 1977

- DeVita Appointment Now Official; Calls For New Chemoprevention Program, More Applied Prevention, July 18, 1980

- Chemoprevention Clinical Trials To Starts In 1982 If Greenwald, DRCCA Board Can Move Fast Enough, Aug. 28, 1981

- Agreement Reached On Most CCOP Issues; First RFA To Be Out March, Awards To Be Made In Fiscal 1983, Jan. 22, 1982

- NCI Implementing Changes In Organ Site Program, Directing Grant applications To NIH Study Sections, Oct. 15, 1982

- CCOPs At Six Months: Some Exceeding Patient Goals, Most Are Meeting Schedules, March 30, 1984

The criteria FDA uses to approve cancer drugs have been the subject of debate since well before the passing of the National Cancer Act of 1971. Many of these debates have played out in The Cancer Letter, and continue to this day:

- Freireich’s Seven Laws To Protect Against Obstacles To Clinical Research, May 14, 1976

- Chabner, FDA’s Temple Continue Disagreement Over Drug Approval, Feb. 10, 1989

- FDA, NCI Seek Compromise On Survival Endpoints, June 16, 1989

- Improved NCI Relations With FDA Cited As Model For Government Accord, Lasagna Committee Says, April 20, 1990

- FDA Oncology Division Director Says Goal to Make Review Process “Predictable”, Aug. 2, 1996

- An “insurgency” targets randomized trials, demands access to investigational drugs, Aug. 5, 2005

- We ask FDA to explain “dangling” accelerated approvals—and this week’s ODAC agenda, April 30, 2021

- Pazdur at FDA-ASCO workshop: Failure to optimize the dose is akin to building a house on quicksand, May 6, 2022

From the beginning in oncology, great promises were made. Sometimes these promises exceeded the scientific realities:

- Reorganization, Money Will Cure Cancer In 21st Century, NCLAC Report Promises, Sept. 28, 2001

- Alliteration And Prayer Were His Tools For Making Progress Possible For People, May 19, 2006

- Scrutiny of caBIG Exposes Conflicts, Bonanza For Contractors, March 18, 2011

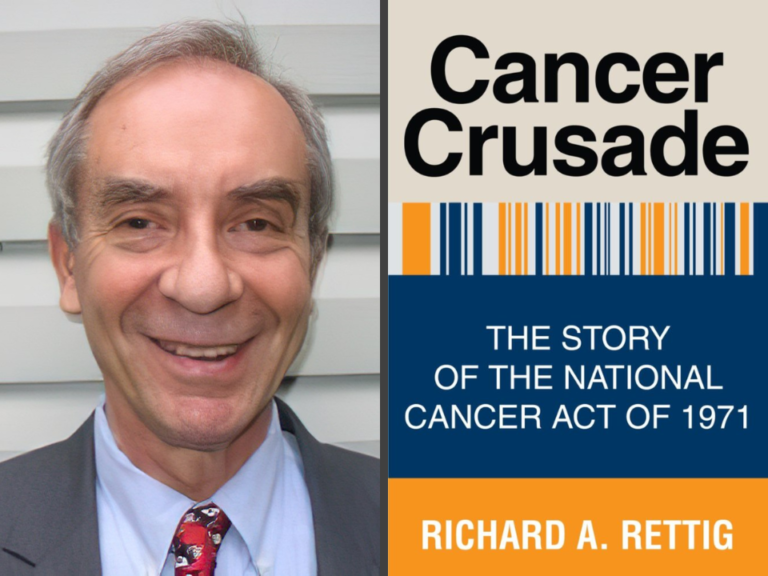

- DeVita: 50 Years of Stories On Cancer Wars and Skirmishes, Nov. 6, 2015

- Book Review: DeVita’s History of Oncology Told with Candor and Optimism, Nov. 6, 2015

Practice-changing discoveries

Over the past 50 years, as scientific understanding of cancer developed, The Cancer Letter was there.

As cooperative groups were reporting practice-changing findings, we were in the front row at press conferences, and on the phone with Bernie Fisher and other pioneers as their studies put an end to radical mastectomies, established the efficacy of adjuvant therapy, and laid the groundwork for chemoprevention:

- Breast Cancer Report To The Profession Suddenly Is a Report To The Nation; Treatment Progress Noted, Oct. 4, 1974

- Breast Cancer A Heterogeneous Disease, Concepts Changing: Fisher, June 13, 1980

- Cancer Prevention: NSABP Publishes P-1 Data, Finds Risk Of Breast Cancer Cut By 49 Percent, Sept. 18, 1998

- NSABP Breast Cancer Prevention Trial Reports Final Results On Tamoxifen, Nov. 25, 2005

- Cancer History Project Panel: How Betty Ford’s and Nancy Reagan’s breast cancer diagnoses changed attitudes to cancer, March 10, 2023

The Cancer Letter was there for the beginnings of cancer immunotherapy, too, even when its promises seemed more akin to science fiction than clinical reality:

- Hammer Gives $100,000 to Expand Rosenberg’s T-Cell Growth Factor Clinical Studies, March 1, 1985

- Rosenberg’s Latest Results: 22% Response Seen With LAK/IL-2, 13% With High Dose IL-2 Alone, April 10, 1987

Discoveries led to paradigm shifts, landmark drug approvals—and landmark controversies. The Cancer Letter covered the development of Taxol, the congressional investigation of its price, and battles over introduction of its generic version:

- Taxol Recommended For Second Line Therapy In Platinum-Resistant Metastatic Ovarian Cancer, Nov. 20, 1992

- Taxol Approved By FDA For Ovarian Cancer; Bristol Sets Price Tier In Line With Platinum, Jan. 8, 1993

- Chabner On Taxol, NSABP: “Makes You Lose Confidence In The Political Process”, May 12, 1995

We were also there for the clinical trials–and approval—of Gleevec, a drug that enabled some CML patients to check out of hospices and return to their normal lives.

- FDA Approves Gleevec In 73 Days, A Speed Record, May 18, 2001

- Hagop Kantarjian: Why Drugs Cost Too Much and How Prices Can be Brought Down, May 31, 2013

- In 1998, a CML patient was out of options. Then she chanced into a treatment–Gleevec, June 3, 2022

We covered the development of Herceptin, a monoclonal antibody for the treatment of breast cancer, and we covered the beginnings of checkpoint inhibitors and CAR T-cell therapy:

- Advisors Clear Herceptin; Find Tamoxifen Indicated For “Short Term Risk Reduction”, Sept. 11, 1998

- New Drug Approval: Groups Urge FDA To Move Quickly On Herceptin Approval, Sept. 18, 1998

- ODAC unanimously recommends approval for CAR T-cell therapy for relapsed and refractory B-cell ALL in kids and young adults, July 14, 2017

- Herceptin: What it took to make it happen, by Robert Bazell, Sept. 20, 2019

- PD-1 Checkpoint Inhibitor Opdivo First to Demonstrate Survival Benefit in Phase III, Dec. 1, 2014

- Accelerated Approval Granted To Opdivo in Metastatic Melanoma, Jan. 9, 2015

- When your harmonica player wins the Nobel Prize, by Rachel Humphrey, Oct. 5, 2018

- Jim Allison believed in the power of T cells—when hardly anyone else did, Jan. 27, 2023

Source: Rachel Humphrey

Scandals, big and small

Oncology is known for big scandals, and the congressional blow-up over allegations of fraud at NSABP was one of the biggest:

- Results of NSABP Studies Unchanged When Falsified Data is Excluded: Fisher, May 27, 1994

- Clinical Trials: Data Manager Falsified NSABP Records On 3 Patients, ORI Says, Feb. 12, 1999

- When Bernie Fisher refused to grovel, Nov. 1, 2019

The NSABP scandal—and its years-long reverberations—gave Paul Goldberg, then a young reporter, a sense of how complex an oncology scandal can be.

When ImClone’s drug Erbitux initially failed to get FDA approval, The Cancer Letter’s investigation turned up an FDA refuse-to-file letter, something known under the ominous acronym “RTF.” We obtained that document.

This led to an insider trading scandal, investigations by the DOJ, SEC, and U.S. Congress. Other sequelae included reorganization of FDA’s oncology shop—and (a surprise to us) a rap sheet for Martha Stewart.

- FDA Says ImClone Data Insufficient To Evaluate Colorectal Cancer Drug C225, Jan. 4, 2002

- Hearing Scheduled To Investigate ImClone’s C225 Development, Stock Trading, June 7, 2002

- ImClone Founding CEO Samuel Waksal Charged With Securities Fraud, Conspiracy, Perjury, June 12, 2002

There were other stories about oncology’s outliers and outlaws, some infuriating, some salacious. Stories we broke have ended up on the CBS newsmagazine show 60 Minutes (twice), the ABC news show 20/20, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The Economist, NPR, and many other news outlets:

- Controversial Dr. Raiko Medenica Sued By Patient; Hilton Head Hospital Reviews His Practices, April 30, 1993

- P-32 Ingestion At NCI Attracts Attention; Similar Cases Seen At Labs In The Past, Nov. 3, 1995

- The Antineoplaston Anomaly: How A Drug Was Used For Decades In Thousands Of Patients, With No Safety, Efficacy Data, Sept. 25, 1998

- ACS-Led National Cancer Dialogue Beset By Patient Mistrust, Lack Of Openness, Jan. 21, 2000

- South African Investigator Bezwoda Admits Falsifying Data In High-Dose Chemo Study, Feb. 11, 2000

- Tobacco Company Liggett Gave $3.6 Million To Henschke For CT Screening Research, March 28, 2008

- Prominent Duke Scientist Claimed Prizes He Didn’t Win, Including Rhodes Scholarship, July 16, 2010

- Slamming the Door: How Al Gilman Taught Texas a Lesson in Science, Jan. 29, 2016

- Prominent GI oncologist Axel Grothey was forced out of Mayo Clinic for unethical sexual relationships with women he mentored, May 28, 2021

Some of our stories contributed to changes in clinical practice. One, a scoop about a study pointing to harm from administering red blood cell growth factors in an effort to push hemoglobin to normal levels, also led to a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court—the Amgen Securities Litigation (The Cancer Letter, Sept. 4, 2015). Another series of stories that changed medical practice and FDA regulations of medical devices focused on hazards form morcellation, a procedure commonly used in gynecologic surgery:

- Danish Researchers Post Long-Awaited Aranesp Results–Ever So Discreetly, Feb. 16, 2007

- Harvard Physician Whose Cancer Was Spread Through Morcellation Seeks to Revamp FDA Regulation of Medical Devices, July 3, 2014

Advocacy, survivorship, and justice

Source: NCCS

Addressing Congress on July 29, 1992, Fran Visco, a breast cancer survivor from Philadelphia, declared, “We will no longer be passive. We will no longer be polite”—and The Cancer Letter’s Paul Goldberg was there.

Breast cancer survivors, learning from AIDS activists, created a national movement. After Visco’s speech, the political structures of oncology were permanently transformed to include patients.

Movements advocating for cancer research became bigger, their demands grew bolder. Public advocacy replaced the old system, where wealthy benefactors (like, for example, Mary Lasker) could influence policy.

Notably, in this new political climate, a broad coalition of groups, spearheaded by the financier and prostate cancer survivor Michael Milken, organized a March on Washington, an event that can be tied to the doubling of appropriations for NIH.

Cancer survivors were being invited to take part in shaping policy that affected them, and descended en masse on Washington, calling for funding, policy change, and health equity:

- Breast Cancer Coalition to Congress: ‘Find a Way To Fund The War,’ Bypass Level Is Not Enough, Aug. 7, 1992

- Milken Calls For Renewed War On Cancer, $20 Billion A Year International Effort, Nov. 24, 1995

- To Wage New War On Cancer, Advocates Plan A Campaign Inspired By Earth Day, Oct. 31, 1997

- The March Attracts Thousands To Rally For Research Funding, Access To Care, Oct. 2, 1998

- Ellen Stovall, Pioneering Advocate for Survivorship, Dies at 69, Jan. 8, 2016

- Manocherian: We have been unapologetic in advocating for 10% annual increases to NIH, April 6, 2018

Today’s oncology is far removed from the 1970s smoke-filled, male-dominated rooms where decisions were made. Addressing health disparities is now one of the mandates for NCI-designated cancer centers; efforts to increase diversity in the workforce and in leadership are required as well.

This shapes a new dialogue on diversity, equity, and inclusion:

Photo courtesy of Pock Utiskul

- #WhiteCoats4BlackLives aims to lead to real change in oncology “I’ve never been more hopeful in my entire life”, June 12, 2020

- Sexual harassment reporting structures in oncology are broken, The Cancer Letter survey finds, Oct. 2, 2020

- First-ever TCL-AACI study of the leadership pipeline points to urgent need for more diversity at elite cancer centers, Oct. 9, 2020

- Cancer centers establish DEI Network as NCI issues CCSG guidelines to enhance diversity in the oncology workforce, Dec. 3, 2021

- “This is not about protecting life”: Supreme Court overturn of Roe v. Wade threatens lives of cancer patients, doctors, July 1, 2022

- More than 500 bills restricting trans medical care threaten LGBTQ+ people with cancer, Aug. 11, 2023

50 years—and more to come

Today, The Cancer Letter’s headlines are dominated by bioinformatics, real-world evidence, artificial intelligence, immunotherapy, precision oncology, the Cancer Moonshot, and the first steps of the recently-established HHS agency, ARPA-H. As the field continues to reorganize itself around new innovations, it’s hard not to see reflections of the early debates about the fundamental principles.

One thing is certain: Oncology will keep evolving, and The Cancer Letter will continue to evolve with it.