Women in oncology who face gender bias know what not to do: seek help from their institutions.

A survey by The Cancer Letter found that women in academic oncology who have encountered gender bias at work overwhelmingly accept the notion that their institutions will fail them, and those who do lodge complaints are, with no exception, disappointed.

In the survey, 62% (n=78) of women said they chose not to report such incidents. Tragically, it appears that they made the prudent choice, because all the women who did lodge complaints said their institution’s response was inadequate or worse. Two said their institutions retaliated, leading up to termination and resignation. (This analysis excludes the six men who responded to the survey.)

Incidents reported in the survey fall into these categories:

- Disparity in treatment, including instances when men are addressed by title/honorific, but women are not,

- Disparity in pay or promotion,

- Inappropriate gender-related remarks,

- Sexual harassment,

- Inappropriate physical contact,

- Gender-related bullying,

- Gender-related shaming.

The survey is a follow-up to a news story that demonstrated that at scientific conferences and other professional settings, women are often referred to by first name while their male colleagues are referred to by titles and honorifics (The Cancer Letter, Dec. 13, 2019).

The survey was distributed via The Cancer Letter’s mailing list and Twitter account, seeking respondents who have experienced gender bias or harassment. The survey was administered before the COVID-19 pandemic.

The survey isn’t designed to measure the prevalence of gender bias and sexual harassment in oncology. The objective is to gather the data, anonymize them, and assess the aftermath in a systematic manner. The responses allowed us to compile a database of cases where the systems have failed—and to draw lessons from what we have learned.

When data on gender bias and sexual harassment are presented—particularly in the #MeToo era—attention must be paid.

Do reporting structures work? Do individuals feel empowered to speak up? Do they feel confident in their institution’s leadership and work culture? What are the outcomes? Do such incidents impact science, productivity and professional standing?

We received 84 responses. Seventy-seven were from women, and some responses describe chilling accounts of misogyny:

- There are numerous episodes through my surgical career of over 20 years. Rude and disrespectful jokes, references to my anatomy. Cornering me in an elevator by a senior attending when I was a medical student, unwelcome touching in front of my husband, salary disparity.

- I have been consistently made to feel that I am unwelcome throughout my career. This included attempts to intimidate me using sexually suggestive comments and physical contact early in my career, to suggestions that I be less successful, because it was agitating my male colleagues later in my career.

- Everyone just ignores any incidents of disrespect/harassment, because nothing comes of reporting it to upper administration.

- Upper administration members (all male) laughed at me in a meeting. Who do I report that to???

A compilation of anonymized responses is available here.

Misogyny—and futility

“These findings speak deeply to the culture of medicine and the very real fears that women have that if they complain about something like that, they will always be identified as a whiner, they will be marginalized, they will suddenly be labeled as someone who is not strong enough, it will be a distraction from their professional contributions, they will bear a stigma. And potentially, they will be further victimized as a result, and face retaliation,” Reshma Jagsi, deputy chair of radiation oncology, Newman Family Professor of Radiation Oncology, Residency Program director, and director of the Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences at the University of Michigan, said to The Cancer Letter.

Jagsi, one of the founders of TIME’S UP Healthcare, is one of a group of experts—directors of cancer centers and researchers of gender bias—who were asked to review the survey data for The Cancer Letter. To eliminate gender bias in oncology, the reporting systems must change, and diverse leadership is key to making the system work, these experts said.

As a result of gender bias, women say they were forced to reconsider their careers and made to doubt their self-worth. Many developed depression. Productivity tanked, scientific collaborations suffered.

“The study as a whole, the incidents of discrimination, harassment—are really shocking and disturbing,” said Leonidas Platanias, director of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center, Jesse, Sara, Andrew, Abigail, Benjamin and Elizabeth Lurie Professor of Oncology, professor of medicine (hematology and oncology), and biochemistry and molecular genetics at Northwestern University.

“This obviously needs to change, and it needs to happen fast. It’s totally unacceptable at all levels,” Platanias said to The Cancer Letter. “It negatively impacts cancer research. These situations can affect how teams function and, ultimately, have a negative impact in research.”

A conversation with Platanias appears here.

A toxic work culture is anathema to team science, said Caryn Lerman, H. Leslie and Elaine S. Hoffman Professor in cancer research and director of the University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“When faculty members are uncomfortable among their colleagues, or do not feel safe, there is a disincentive to participate in team science. This not only may affect scientific productivity, but also could contribute to a sense of isolation and demoralization among women faculty,” Lerman said after reviewing The Cancer Letter‘s data.

Institutional betrayal

“People who are targets of workplace discrimination or harassment often also experience institutional betrayal, a term developed by Dr. Jennifer Freyd and Dr. Carly Smith, to describe the failure of an institution to prevent or respond supportively to wrongdoings by individuals committed within that institution,” Ally Coll, president and cofounder of The Purple Campaign, said to The Cancer Letter.

In the era of #MeToo accountability, why do people avoid reporting gender bias?

Here is a selection from the answers we received:

- Boys’ club; no guarantee that things are kept confidential.

- There’s not a good culture for reporting this at my institution.

- Worried about retaliation.

- I didn’t want to make a fuss.

- It didn’t seem offensive, but the norm.

- Unresponsive in the past.

- Fear of retaliation from [the] chair.

- It was part of the overall culture due to lack of women as faculty.

- It would have made the situation worse.

- Satisfaction unlikely, bullshit likely.

“All of these are saying the same thing,” said Christina Chapman, assistant professor in the Department of Radiation Oncology at University of Michigan School of Medicine, Center for Clinical Management Research, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, “They’re saying the same thing in slightly different ways, which is that our reporting structures are inadequate, because the people who comprise them have bias. We know that this is harming. It’s harming our science, harming our patients.”

Many respondents suggest that gender bias is part of a workplace culture where harassment is the norm.

The data point to a pervasive sense of futility, said Narjust Duma, assistant professor of medicine in Thoracic Oncology at University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center, the lead author of the path-breaking paper focused on disparity in the use of honorifics at a meeting of a professional society.

“A lot of people come to that conclusion, because some of these women have reported harassment, or have reported discrimination, and nothing has happened. The challenge is that once people have reported the effects, one, they’re downplayed. Two, no actions are taken, so you feel like, ‘Why are you going to put forth the effort?’” Duma said after reviewing The Cancer Letter‘s data. “When a woman reports harassment, she is also put at risk that she will later be harassed for reporting on it.”

Writes one respondent:

The person who sexually harassed me was my mentor. When I didn’t give him what he wanted, he was furious, made my life a living hell at work, and dropped me as a mentee. He stifled my academic career. He has tried to tarnish my reputation among national and international leaders in my field by telling everyone I made up lies about sexual harassment so that I could take over his ’empire.’

Of the 84 survey respondents, 75% said an incident negatively or very negatively impacted their productivity and morale. Personal well-being was also severely compromised: 73% of respondents ranked the impact of the incident as “negative” or “very negative.”

Pamela Kunz, a GI oncologist, is one of the few who spoke out.

Now leader of the Gastrointestinal Cancers Program and director of GI Medical Oncology at Yale Cancer Center, Kunz spoke with The Cancer Letter about years of gender-related microaggressions she experienced in her previous position at Stanford School of Medicine. This history caused her to change jobs, she said.

“I think there’s often a reluctance to do anything to the perpetrators when they are full professors, or bring in a lot of philanthropic money, or have a lot of grants, or have longevity at an institution,” Kunz said to The Cancer Letter.

A conversation with Kunz and a response from Stanford appear here.

Respondents were asked to fill out the survey only if they experienced an incident of gender bias. Of the 84 respondents to The Cancer Letter‘s survey, 66 identified as white, 14 as Asian, and four as Hispanic or Latino.

It may be noteworthy that The Cancer Letter did not receive any responses from Black women. Women of color can feel harm even more acutely, Jagsi said.

“The limitation of any small dataset is that we can’t even begin to imagine what the experiences are like of individuals who inhabit multiple minority identities,” Jagsi said. “And, quite conceivably, the systems might function even worse for individuals who are in multiple vulnerable subgroups. I think that’s important to call out.”

How can institutions do better?

“Culture change and transformation are absolutely necessary, and so, there need to be proactive initiatives,” Jagsi said. “Target the culture at the organization—make it clear that the organization no longer, if it did before or never did, tolerates this kind of behavior.”

Improving diversity at the top rungs of institutions is crucial to reducing gender and racial inequity. At this writing, nine of the 71 NCI-designated cancer centers are headed by women directors, and only one cancer center director is Black.

Next week, The Cancer Letter will publish new data on diversity among leaders of top academic cancer centers in the U.S. and Canada. The survey was conducted in collaboration with the Association of American Cancer Institutes.

Failure rate: 89%

Eighty-nine people responded to The Cancer Letter‘s survey. Eighty-four responses cite specific incidents of gender bias. Five responses were omitted: four because they cite no incident, and one because it contained abusive language and was not germane to the questions.

The average number of incidents per respondent is 2.6. (Fig. 1)

- 73% (61) report a disparity in treatment (i.e. your male colleagues were addressed by title/honorific, but you were not),

- 58% (49) report a disparity in pay or promotion,

- 44% (37) report inappropriate gender-related remarks,

- 24% (20) report sexual harassment,

- 24% (20) report inappropriate physical contact,

- 20% (17) report gender-related bullying,

- 14% (12) report gender-related shaming.

Writes one respondent:

I cannot believe that any woman could identify just one, or seven, or 10 incidents to discuss in this survey. You might hypothesize that those taking the time to respond to this survey are an isolated few who have had rare negative experiences. That is not the case. I’m a 60-year-old woman who is trusted as a good sounding board, a good friend. I don’t know one woman, who I have worked with, who has not experienced unwanted and uncomfortable sexual pressures. The design of this survey may be the equivalent of asking someone whose home was destroyed and family members killed and asking them if there has been “an impact on their personal well-being.”

A majority of respondents—77%—work in academic medicine. Others are employed in the government (8.5%), advocacy (5%), community health (5%), industry (3.7%), and nonprofits (1.2%). (Fig. 2)

Fifty-three (63%) identify in an optional question that they work in oncology.

Respondents demographic and professional data is available below. (Fig 3, 4, 5)

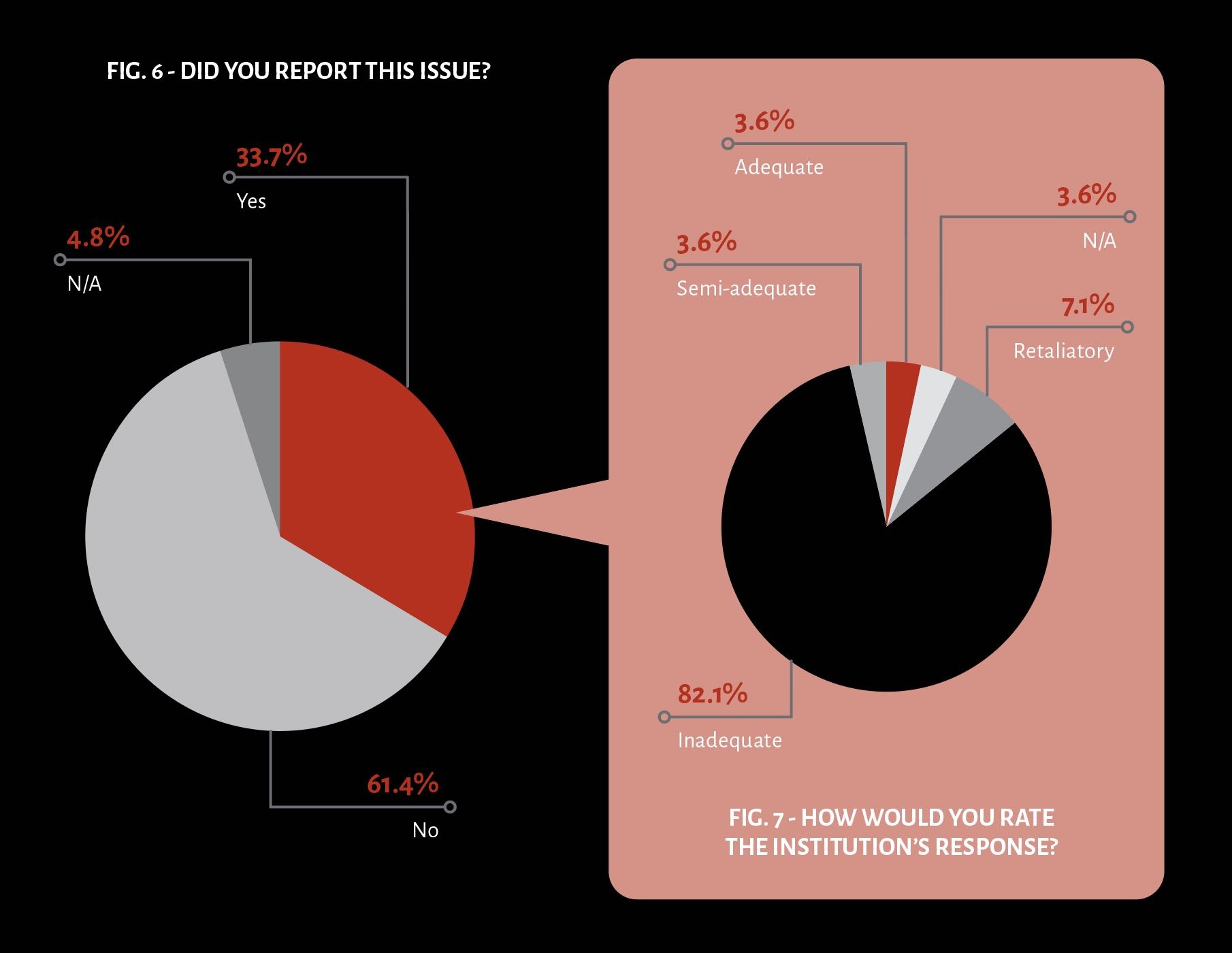

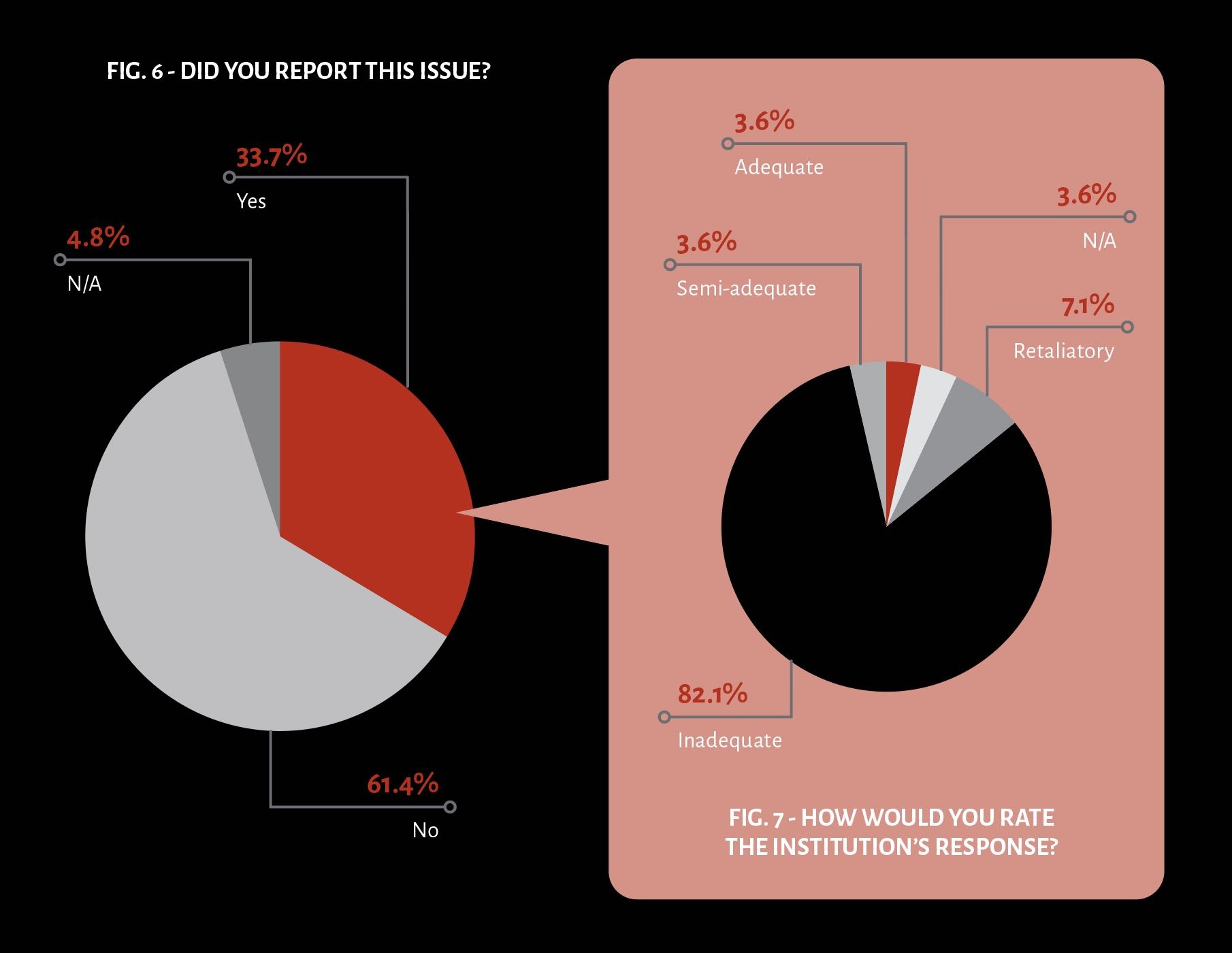

Of all respondents, 61% did not report the incident through institutional reporting mechanisms. Only 34% of respondents reported the incident. (Fig. 6)

Of the 28 who chose to report an incident of gender-related bias, 82% said that their institutions’ response was inadequate, and one said it was adequate on one count, but not another. Another two women said their institutions retaliated, leading up to termination and resignation. (Fig. 7)

Based on these self-reporting measures, this would amount to an 89% failure rate. Only one individual characterized the institution’s response as adequate. That individual is a man. Among women, the failure rate is 100% (n=27).

Feelings of depression, isolation, doubt, and anger were noted again and again in response to the prompt, “describe the impact of this incident.” In optional short answer questions, 13 respondents (15%) said they left their positions—and some, their profession—as a result.

Harassment can result in a feeling of being trapped, said Awad Ahmed, a radiation oncologist at Jackson Memorial Hospital and University of Miami, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, who conducts research on gender bias in radiation oncology.

“What a lot of people don’t realize when it comes to medicine is that it’s a completely different ball game. Lateral movement, or starting all over again isn’t as easy as it is in other professions,” Ahmed said. “To just up and switch is not easy. When you bring these issues forward, you’re really risking a lot. I don’t know if a lot of people realize that.”

Respondents were asked to assess their institutions’ ability to address gender bias:

- As a result of the incident, did you feel:

- Empowered to speak up? (63% negative)

- Confident in the ability of the leadership of your institution to address gender bias? (76% negative)

- Comfortable with your institution’s work culture? (67.1% negative)

- Comfortable continuing to be a part of your institution? (48.1% negative)

The responses, graphed below, demonstrate a culture of toxicity. (Fig. 8)

In questions regarding their personal well-being and morale, respondents were given options to rank the impact from “very negatively” to “very positively”:

- How did the incident impact your:

- Productivity and morale? (75.1% negative)

- Professional standing? (40.1% negative)

- Personal well-being? (76% negative)

These responses are graphed below. (Fig. 9)

The Cancer Letter‘s survey results appear to be consistent with other studies across medicine.

A 2018 report from the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine demonstrated that female medical students were 220% more likely than students from non-STEM disciplines to experience sexual harassment—and that they were more likely to be harassed than students in other STEM disciplines as well.

Black and other minorities can be reticent to fill out surveys of this sort, experts say.

“A lot of times, when you are such a small number, even when people say it’s going to be an anonymous survey, you have doubts as to whether it ever truly be anonymous,” Hopkins’s Deville said. “It’s not hard to figure out who you are the minute you say you are a Black female ENT surgeon respondent. There’s probably a small enough number that one could start to think about and figure out who that person was.

“You may have some of those kinds of sentiments as well—I’m not even going to bother, I’m just gonna keep trying to do what I need to do or, my work or my job, or not take time for this survey, or not take time to try to speak up and address this issue. You’re just trying to get through your day, or maybe navigate through the system in a different way.”

The cost of failure

Asked to describe how the incidents made her feel, one respondent wrote: “Depressed; distraught; unable to focus or feel dedicated to my work.”

Others wrote:

- I was burned out and clinically depressed. I am considering leaving the institution at which this happened, but have not a final decision.

- Being treated as less important undercuts confidence in speaking up, etc.,

- Created an atmosphere of anxiety whenever I had to be around the people responsible for the incidents.

- The constant drumbeat of a lack of respect has been fairly stressful and has made it difficult for me to advocate for resources and change.

- Emotional abuse, severe depression which took over a year to get back to “normal.”

- Professional standing is neutral because I am still worried about the impact of these incidents on my reputation. It also took a lot of time for me to even take the step of filling this survey.

- I am not going to dredge up those thoughts and feelings.

“How can you truly be your best if you don’t feel like you are in an environment that values these kinds of issues, and has zero tolerance?” asked Deville. “That’s not really an environment where you’re going to be able to be successful and be your best self.”

Gender bias makes you question your own worth, said Tatiana Prowell, associate professor of oncology in the Breast Cancer Program at The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins and Under Armour Breast Health Innovation Center.

“It may cause them to question the value of their own contributions and thus disengage from the team. This impacts the individual first, but over time it also harms institutions as morale falls, and you begin to see difficulties with retention and recruitment,” Prowell said to The Cancer Letter. “In the best of cases, we find women leaving to more supportive institutions that will make better use of their talents. In the worst of cases, we lose them to the field of science and medicine entirely.”

The psychological toll of gender-related harassment ultimately affects research and patient care.

“Women are in positions and do important work that advances our field and that saves lives. If women are less productive, whether it’s because they are doing more cooking and cleaning, or whether it’s due to sexual harassment and sexual assault—strike one is the fact that it occurs. That results in a lot of psychological distress,” Chapman said.

“The psychological distress removes women’s time away from the science, which impacts our patients, which impacts the field.”

The mechanisms of mistrust

Women who responded to the survey were particularly unhappy with reporting mechanisms at their institutions:

- Institution was so unresponsive that I sought legal counsel and filed charges. Institution was so slow to react that it required a year of negotiations to settle the issue.

- There has been little change, as the problem starts at the top.

- The person that sexually harassed me was given the option to resign instead of being fired. This person has a position of leadership where he can continue to wield power over me and other individuals he harassed. I wrote a letter to [redacted] letting them know about his history and never got a response and this individual remains in the leadership position.

- Though the behavior from this individual did get a little bit better, the overall toxic workplace environment did not. I was ostracized both socially and professionally from my colleagues. I was told that my performance on particular, difficult, laboratory procedures was not satisfactory, and I was essentially given an ultimatum: reach a certain success rate, or leave. I was given very few resources to improve these skills and had to perform under immense pressure from my co-workers. I chose to leave this job because 1) I was in school at the time and knew I wanted to switch to a different field upon graduation, and 2) I was so stressed out all the time from the anxiety of this job that my mental health suffered greatly.

- Was told my boss maintained an adequate professional standard because he said good morning regularly and was friendly.

- Everyone just ignores any incidents of disrespect/harassment because nothing comes of reporting it to upper administration.

- They did not acknowledge the notice issued by the human rights commission.

- My boss (cc director) literally pretended to get a phone call and walked out of the room when I raised the issue of lack of promotion and differential treatment.

Change starts with calling out bad behavior, said Malika Siker, associate dean of student inclusion and diversity in the Office of Academic Affairs, associate professor in the Department of Radiation Oncology, student pillar faculty member, at the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Institute for the Transformation of Medical Education at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

“Every woman should take some time to consider the things that are happening to them. If they’re experiencing any type of harassment, bullying, or even just unprofessionalism—it can take courage to call it out,” Siker, also academic vice chair of the Community Advisory Board at MCW Cancer Center, Medical College of Wisconsin, said to The Cancer Letter. “That’s a really hard thing to do, especially if someone doesn’t feel safe, or the institution is not in a position to support them, but it has to start somewhere.”

How would you know that your complaint has been taken seriously? That an investigation has been initiated? Or even that your harasser has been contacted as a result of your complaint?

“What often happens, in my experience, is that these kinds of complaints are actually taken very seriously—but the complainant doesn’t know that, and the complainant feels like nothing has been done,” Jagsi said. “Some of the dissatisfaction, or the sense that the process was inadequate—may reflect the fact that human resources and confidentiality concerns about protecting the identity and actions taken against the perpetrator limit the ability to inform the complainant about what exactly was done.

“Reporting isn’t the ideal mechanism to address challenges like this because there are so many barriers, including fears of retaliation, marginalization, and stigmatization on the part of the target of the behavior, which often cannot be masked sufficiently to be reported anonymously.”

Four respondents cited “fear of retaliation” as a reason for not reporting to their institutions. Such fear is common, said The Purple Campaign’s Coll.

“Retaliation is a really common reason of why people are fearful of reporting harassment and discrimination. That study shows that they’re right to fear that, because it’s still so prevalent of a problem when people do report,” Coll said.

[Disclosure: Coll is a step-daughter of Paul Goldberg, editor and publisher of The Cancer Letter.]

The Equal Employment Commission in 2016 found that across all industries, 70% of people who experienced workplace harassment didn’t report it to a manager, supervisor or union representative. Worse, 75% of those who reported such incidents experienced some form of retaliation.

Retaliation is illegal—sure. But it exists.

“Companies always have anti-retaliation policies in place, but to what extent they’re enforced, is the question. And they’re not always enforced consistently,” Coll said. “Is somebody going to report retaliation when they’ve already reported an incident, and it’s resulted in that adverse consequences for them in the workplace?”

Perhaps a bureaucratic tendency to wish the problem away and hide the garbage is at play here, Chapman said. “I think what that tells us is that we need to stop, and we need to ask ourselves why,” she said. “The answer is that we haven’t made the progress. We need to, because the system is still run by individuals who continue to pass by it.”

Even the perfectly configured reporting system, if it existed, would get you only so far. “By the time we are talking about reporting mechanisms and responses to discrimination, the damage has already been done, so our focus long-term has to be upstream of this,” Prowell said.

The Vanderbilt Center for Patient and Professional Advocacy proposes one system, CORS—which is used at many institutions in academic oncology to promote conflict resolution.

The CORS program uses a tiered approach:

- “Recorded reports are reviewed to ensure allegations do not require mandated reviews or investigations (e.g., impairment, bias, inappropriate touch, fraud, harassment,), but can simply be shared in a respectful, non-directive fashion during an informal conversation such as one might have with a colleague over a cup of coffee.

- When patterns appear to emerge, CPPA supports peer-delivered Level 1 Awareness interventions with local and national peer comparisons as described above. Most clinicians respond to awareness interventions.

- Some, however, are unable or unwilling, and these clinicians are escalated to Guided Interventions by Authority (Level 2). Level 2 interventions include a written corrective plan developed by the individual’s authority figure (a department chair, chief medical officer, or other leader).

- A very small number may not respond to the plan and are elevated to Level 3 disciplinary action as defined by organizational policies, bylaws, contracts or other governing documents.”

“It’s their pyramid for what you do. You can provide routine feedback if there’s a single concern. You investigate whether there is merit. If it’s egregious, you escalate it to Level 3, which is disciplinary intervention—but you also can have mandated reviews and escalate it,” said Jagsi, whose institution, the University of Michigan, uses this approach.

The systems in place at Michigan haven’t prevented sexual misconduct allegations from slipping through the cracks in the past.

The second-highest administrator at the university, Martin Philbert, provost and executive vice president for academic affairs, resigned amid allegations of sexual misconduct earlier this year. Philip, who faced multiple formal complaints for years, left the university last June.

“Passing the trash”

Writes one respondent:

The #MeToo movement was great to raise awareness and empower women. But if institutions are just going to let people resign quietly, so that they can continue to harass other people and not actually be held accountable for their actions, then they are not really addressing the issue. This is similar to what happened in the Catholic Church, where priests were moved from parish to parish instead of actually facing consequences of their actions.

“When someone is dismissed for an allegation of this sort, they often get hired elsewhere, that phenomenon is so common as to have an actual name in the business, which is called ‘passing the trash,’” Jagsi said.

Jagsi addressed the phenomenon at a meeting of the Council of Deans earlier this year—the very people who “are passing the trash to one another,” she said.

“We have a real problem in medicine, and academic medicine, of individuals who are known perpetrators of really egregious behaviors getting passed around to several institutions before, finally, someone realizes that this has happened at several institutions—and it hopefully comes to public attention and it stops,” Jagsi said.

The practice is pervasive. “This is a common occurrence, in industries where people will leave—sometimes voluntarily, or sometimes they’re terminated, and seek employment elsewhere,” Coll said. “This is a common occurrence with sexual harassment, and with men harassing women, but it’s also something you see with other forms of harassment and discrimination—if you have somebody who’s been making racially insensitive comments, for example.”

Joleen Hubbard, consultant, practice chair, and vice chair in the Division of Medical Oncology and Department of Oncology at Mayo Clinic, said she is familiar with situations where harassers have stayed in powerful positions, despite leadership knowing better.

“That person could retaliate against many, many people within that position. The fact that this person’s continued to be allowed to hold a position of leadership, even though many people know the underlying stories, is really disturbing,” she said.

Uncertainty prevails: a dean may pass one item of trash knowingly and unknowingly accept another. “They recognize that, yes, it seems like a good deal to hand off the trash to someone else—until they recognize that what’s happening is that someone else is handing them the trash, too,” Jagsi said.

A system of accountability would be good to have. “I don’t want a system in place so that this person never gets another job again. But I do think that other employers should probably be aware this person had a corrective action or had a serious harassment suit filed against them—or that they left under investigation, or under an unfinished claim,” Hubbard said. “There needs to be some sort of alerting system, otherwise this is going to perpetuate.”

If a harasser brings in funding, the department can be harmed financially if that person goes elsewhere. The trash stays put and the institution keeps the money. “This is a pattern where employers, rather than addressing the issue, choose to look the other way, particularly where it’s a very valuable employee involved,” Coll said.

One respondent offered an example:

The individual was moved out of their leadership role, but given another leadership role on campus with a multi-million retention so they didn’t lose their grant funding.

“[The institution] needs to recognize that they need to subsidize the good behavior,” Chapman said. “Essentially, they need to say to a chair, ‘You got rid of this very problematic person who broke the law, or violated our values, and was having a negative impact on our science and our field—and we recognize that, in many ways that is the right thing to do, but also a courageous thing to do.’”

Usually, a person with a history of harassment can continue to receive grants. NIH grantmaking policies leave it to institutions to regulate ethics of their employees and is therefore limited in what it can do.

Here is what NIH says about sexual harassment:

“While this communication does not constitute or substitute for a report of sexual harassment for legal action or investigation, NIH will follow up with the relevant applicant/grantee institution on all concerns related to NIH-funded research. NIH also strongly encourages people to report allegations of sexual harassment or assault to the appropriate authorities, which may include your local police department or your organization/institution equal employment opportunity or human resources offices.”

Parity is not enough

In an analysis of 6,030 faculty from 265 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education oncology programs, women faculty represent 35.9% of the total faculty body in medical oncology, radiation oncology, and surgical oncology programs.

Representation of women in leadership positions is lower: 24.4% overall (medical oncology, 31.4%; radiation oncology, 17.4%; and surgical oncology, 11.1%).

Representation of women in chair positions is lower, with only 16.3% of departments chaired by a woman (medical oncology, 21.7%; radiation oncology, 11.7%; and surgical oncology, 3.8%).

In some subspecialties, the gender gap is unlikely to be closed anytime soon. Consider radiation oncology. A study by Holliday et al. notes that over the past 30 years, the percentage of women in the academic radiation oncology physician workforce has increased by approximately 0.3% per year for residents and faculty. (By way of comparison, the percentage of women fellows and faculty in medical oncology have increased by 1% per year during the same period.)

“We’re almost about at parity in medical oncology training, whereas in radiation, in that paper we found it would take 50 years for women to reach parity and representation in radiation oncology,” Deville said to The Cancer Letter.

The proportion of women among medical oncology trainees peaked near gender parity (48%) in 2013, but the proportion of women among radiation oncology trainees peaked in 2007 at 35%—and has declined since, the study shows.

“The exact causes for this ongoing gender disparity are unclear, but barriers that may contribute include unconscious bias, sexual harassment and overt discrimination, collisions between biological and professional clocks, and lack of radiation oncology exposure and mentorship for female medical students,” the study states.

How does this affect the culture within radiation oncology?

Another study, a survey of women in radiation oncology residency programs 2017-2018 authored by Osborn et al., demonstrates that gender bias and an absence of mentorship may contribute to attrition of women from the radiation oncology workforce.

“Over half (51%) reported that lack of mentorship affected career ambitions. Over half (52%) agreed that gender-specific bias existed in their programs, and over a quarter (27%) reported they had experienced unwanted sexual comments, attention, or advances by a superior or colleague,” the study states.

“Whatever you find in terms of medical oncology, you have to multiply by a factor, because the diversity in radiation oncology is much less than you see in medical oncology,” Ahmed said to The Cancer Letter.

The culture of gynecologic oncology suggests another problem: that gender parity in the workforce doesn’t guarantee gender equity.

Women account for 51% of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology membership, but are underrepresented among leadership in gynecologic oncology. A study by Tempkin et al. demonstrates that women in gynecologic oncology are underrepresented in leadership roles.

“If you look at the folks we are training today in gynecologic oncology, there’s a ton of women that we are training, but if you look at the leadership, even among the cooperative groups—on who is actually leading these clinical trials, who is actually on the podium, it’s still overwhelmingly men,” said Don Dizon, director of Women’s Cancers at the Lifespan Cancer Institute, clinical director of Gynecologic Medical Oncology, and director of Medical Oncology at Rhode Island Hospital.

Another study, which surveyed U.S.-based members of the SGO, found that 71% of female gynecologic oncologists reported sexual harassment in training or practice.

“The training environment is still not as nurturing as it could be. It’s forcing people to really reevaluate their ambitions. Some may choose to leave academia, and some may choose to just try their best. That group is probably most at risk for psychological demoralization,” Dizon said. “I know several folks who decided just to bug out and go into pharma, for example, because of it.”

Another problem: women in gynecologic oncology aren’t paid as much as men. A study presented early this year at SGO’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer reported that “more than 75% of female providers in academic practice make below the median salary for gynecologic oncologists observed in this survey.”

According to the study, the median salary for men was $500,000 a year, while women were earning $380,000.

“The minority tax”

“There’s research that shows that women of color are not only more likely to be targets of harassment, but also less likely to be believed when they come forward to report. And I believe that is largely due to implicit bias,” Coll said.

“I think it’s really important for everybody, especially managers and supervisors, to undergo implicit bias training. We also really encourage organizations to have uniform and consistent policies and approaches to all forms of workplace harassment and discrimination,” she said.

Women in underrepresented minority groups face an additional obstacle known as the “minority tax.”

“First, you have to acknowledge that the problem is there, that intersectionality is real. For example, you have to pay two taxes,” Duma said. “If you’re in an intersection and you get hit by a car, that’s the gender bias tax. But if you get hit by a car, and then a bus, and then a bike all at the same time—that’s the intersectionality, when you have to pay so many taxes.”

Black women make up 13% of the U.S. population. In medicine, only 2.3% practicing oncologists self-identified as Black or African American, and 5.8% practicing oncologists self-identified as Hispanic, according to a 2017 survey by ASCO.

“Even just to do another survey is already more taxing for Black women, because there’s already the minority tax,” Chapman said. “They already have more societal barriers—have less time to spare—have less free psychological health. It’s already hard to bring people in, but I think it’s critical to do so.”

Change starts at the top

More than three-quarters of respondents (76%) to The Cancer Letter survey said they have little to no confidence in their institutions’ leadership to eliminate gender bias in oncology.

Leadership diverse in gender and race could help improve this metric, University of Miami’s Ahmed said.

“At the heart of it, having real leadership—not just titles—that reflect the diversity of the workforce, or the professional organization, is really integral,” he said.

Alas, leadership, too, can be tokenized. Writes one respondent:

Gender bias is a form of bullying, and extensive education is required to change the gender issues. Assertive women are experienced and very capable, not “bitches,” assertive men are often overrated and less capable than their female equivalents—especially the more they rise in leadership. Very high in leadership, women might not always be the best role models—they went through so much, they might have taken bad habits to survive.

Sometimes, women in leadership are used as cover for bias against other women, Chapman said.

“Women in leadership roles can similarly be pressured and manipulated into furthering these systems of gender-based discrimination,” she said. “The difficulty there is that there’s the appearance of objectivity. When you put women into leadership roles, there is the appearance of diversity, equity, and inclusion in that institution—when the woman may really be nothing else but a tool to further patriarchy and to further white supremacy.”

The phenomenon of women perpetuating sexism appears to figure in gynecologic and breast oncology, Lifespan’s Dizon said.

“What I have, unfortunately, found is that even women in power may be blinded to the inequities that are playing out in the way they might interact with female junior colleagues. They may not be as willing to take someone who’s going to be their competitor on as a mentee,” Dizon said. “I think that that just speaks towards the value that women feel they have within their divisions. You might be an assistant associate or even a full professor—there’s not this sense of security in your role. I don’t know how much that is subconsciously playing into the not-so-nurturing environment for women in medicine, even when it comes to women in power.”

How effective can reporting mechanisms be if the people in power aren’t committed to enforcing them?

“A policy or procedure may or may not be as impactful as just having women in leadership—you have to review what is actually happening in your immediate environment that either does or doesn’t foster diversity and inclusion from a gender perspective,” Deville said.

There are concrete steps to take when hiring for leadership positions, said Emma Holliday, assistant professor in the Gastrointestinal Radiation Oncology Section at MD Anderson Cancer Center, who studies gender bias in oncology.

“You can’t just say, hire some women of color. It’s got to be a process where the change starts from the top, where you give more people a seat at the table in selecting the candidates for leadership and in the interview and selection process,” Holliday said to The Cancer Letter.

Reporting can be optimized

Trash-passing can be prevented.

“Saying that someone lost their job for this type of behavior in the past year can be very powerful. You can’t necessarily say this person was let go because of this, especially because of these nondisclosure agreements,” Jagsi said. “But you absolutely can say, ‘In the past year, someone was let go because of a concern about professionalism and sexual harassment,’ if that’s the specific concern.”

Coll proposed a solution: employers would disclose the reason for someone’s termination, even if it’s done internally.

“That can go a long way toward creating more transparency,” Coll said. “If everybody in the workforce knows that they were terminated for a violation of this kind, it’s more likely that it’ll come up in a future reference check or a future job search.”

Privacy issues are a concern, too, Coll said.

“One balanced approach that I like is to disclose that the person was terminated because of a code of conduct violation, without necessarily needing to get into all of the details of exactly what occurred,” she said. “At least that way people are on notice that they were terminated because they violated the company values or specific policies that are in their code of conduct.”

Often, reporting systems don’t provide the option of anonymity. If there is no HR system in place, then the person who was harassed has only two options: staying quiet or letting their bosses know.

“We need both formal and informal reporting systems,” Jagsi said. “There needs to be an option for anonymity. There needs to be inspiration drawn from things like campus sexual assault reporting processes, whereby someone can make a confidential report and say, ‘I don’t want to be contacted about this unless a certain number of other individuals also report this particular perpetrator. In which case I feel like there’s sufficient strength in numbers that I will speak out about my experience.’”

Solutions

What would an appropriate institutional response look like?

Here is what the respondents wrote:

- Change their behavior, discuss it at a meeting, present the facts.

- More open and inclusive discussions of new initiatives and a concerted effort to increase gender and racial diversity among senior leadership.

- To acknowledge the sexism in its approach to administrative leadership and try to equalize the balance of opportunities.

- Real training of the men to recognize their biases would be helpful but will never happen.

- To simply listen to me and not punish or retaliate against me for speaking out.

- Termination of the individual regardless of how much grant money they bring. Abuse should not be tolerated.

- Fire the offender instead of the victim.

- An investigation. The perpetrator should have been removed from their position.

- Providing parity in a more rigorous manner rather than waiting for individual complaints.

- Immediate action taken against the perpetrator (losing privileges, bonus money, his endowed chair, other).

- Very simple—acknowledgement, a simple apology and corrections of the many wrongs.

- Put women and minorities in leadership positions in proportion to the population.

What sort of policies and directives can institutions implement to eliminate gender bias?

Acknowledgement of incidents and consequences for the perpetrator would be a good start, some respondents said.

Others said leadership change would be an appropriate first step. Here are some of their suggestions:

- It has to be more than bias training.

- Each search committee should have a specific charge to increase diversity of applicants, and to more carefully consider gender and race in candidate selection. Implementation of meaningful unconscious bias training.

- For one thing, the university does not have an ombuds position. The institution seems to think that a monthly “women in cancer” funded lunch will placate the NCI for the support grant renewal, and I suspect they are correct.

- A zero-tolerance policy on sexual harassment and gender discrimination. Flexible reporting structures. Transparency in pay and promotion.

- I think that continued trainings in bias, with practical examples, would be helpful. I think it would be more impactful if stories within the institution or department were anonymized and used as teaching examples. Most people go to these types of training somewhat removed from the events or repercussions because the examples always seem to happen “elsewhere, but not here”.

- Harassers and discriminators need to be called out publicly; only then will it slow down. Getting away with it and being told to stop just doesn’t work.

- The institution lacked women in leadership. If more women were there, I think this may not have happened.

- Include questions about mentorship and career advancement opportunities for junior faculty in supervising faculty’s annual review.

- Leadership at the very top should resign, or secure a professional service to assist in confronting their biases. The culture of retaliation needs to stop before gender bias can be addressed.

“We have to be intervening to stop discrimination before it happens. If the solution to discrimination is diverse leadership, then we have to devote energy to nurturing a deep pool of excellent candidates,” Prowell said. “That requires investing in the pipeline all the way down to high school, or even middle school, and doing the hard work of asking why, on an institutional and societal level, we see so much attrition of women and people of color.”

Dizon suggested a diversity quota that would ensure that the makeup of leadership in oncology better represents the entire workforce—similar to the goals NIH sets out for enrollment in clinical trials.

These findings speak deeply to the culture of medicine and the very real fears that women have that if they complain about something like that, they will always be identified as a whiner, they will be marginalized, they will suddenly be labeled as someone who is not strong enough, it will be a distraction from their professional contributions, they will bear a stigma. And potentially, they will be further victimized as a result, and face retaliation.

Reshma Jagsi

“When we open clinical trials, NIH requires us to fill an estimation of how the volunteers are going to fall in by race. We have to do these projections when we do our clinical trials, because this is going to give the NIH or the NCI some idea of how we’re going to attract a diverse group of volunteers, but also it’s going to hold our feet to the fire,” Dizon said. “We don’t do that in medicine. We don’t say, ‘Okay, you’re a chair. This is a composite of your faculty—where do you want it to be in five years?’ That’s something that we as a field need to sort of start thinking about—real metrics to prove we’re making a difference.”

To eliminate gender bias, institutions must be proactive, experts say.

Bystander intervention is one such measure that encourages “ground-up change by empowering allies and creating ‘up-standers,’” said Jagsi, who published her findings on the subject in the New England Journal of Medicine. “And ultimately, it’s important to recognize that sexual harassment is not only a driver of gender inequity—but that gender inequity is the environment within which sexual harassment thrives, so, interventions to promote gender inequity more generally are extremely important.”

Ten-minute online videos and superficial trainings will not cut it.

“Having clear policies that are thoughtfully developed, and then disseminated to the audience of employees so that they realize that there’s no institutional tolerance—and really proactively enforced, so that they have real teeth, is so critically important,” Jagsi said. “That has to come from the top.

“Leadership really has to realize that this is an issue that is compromising the ability of the organization to deliver on its mission.”