In a first nationwide study of its kind, two researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Anna Lee and Fumiko Chino, set out to answer two questions:

Did Medicaid expansion, as part of the Affordable Care Act, translate into a greater decrease in cancer mortality rates in states that adopted the expansion?

How did the expansion affect the underserved communities—black, Hispanic, rural, etc.—that Medicaid is designed to help?

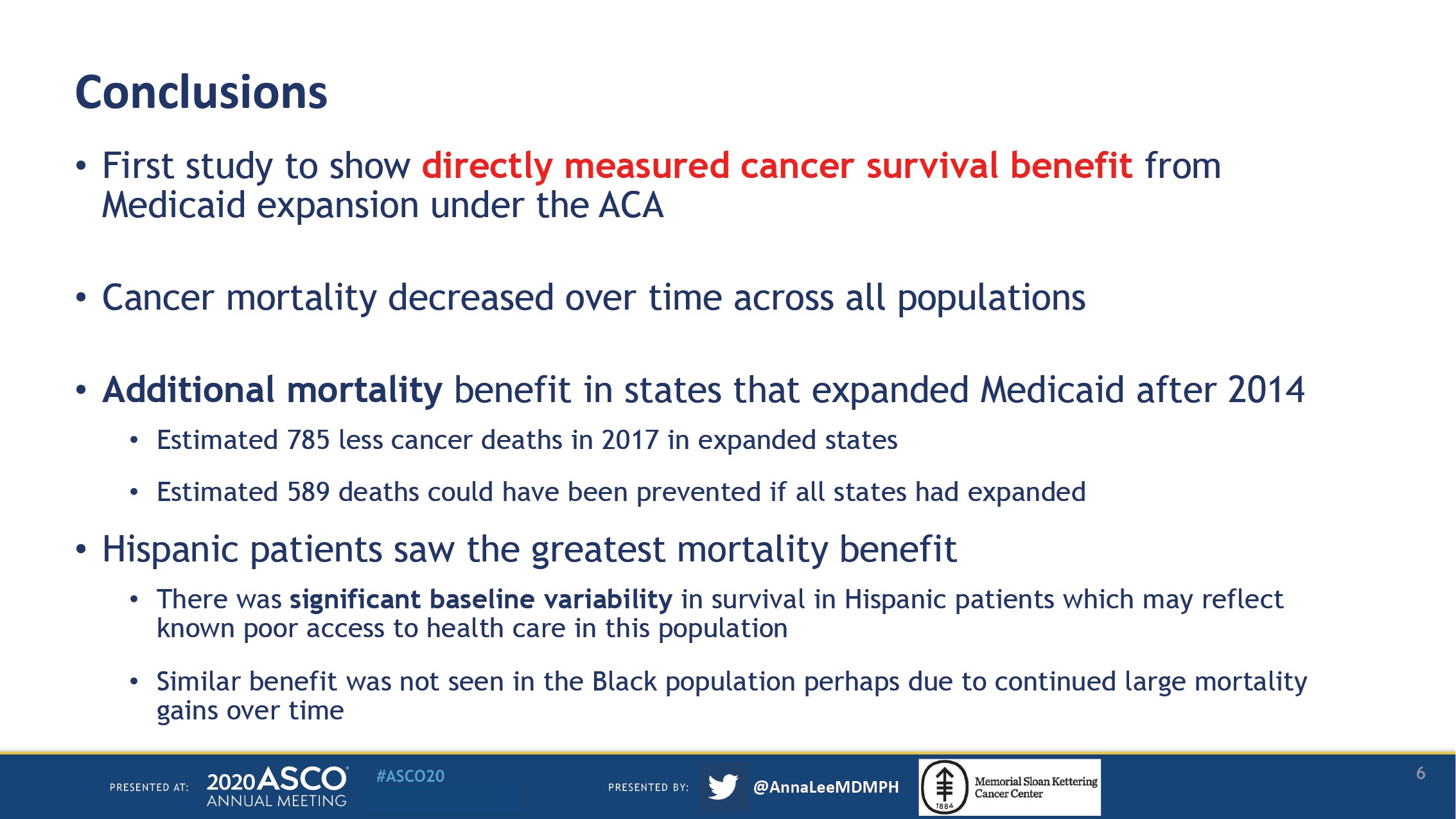

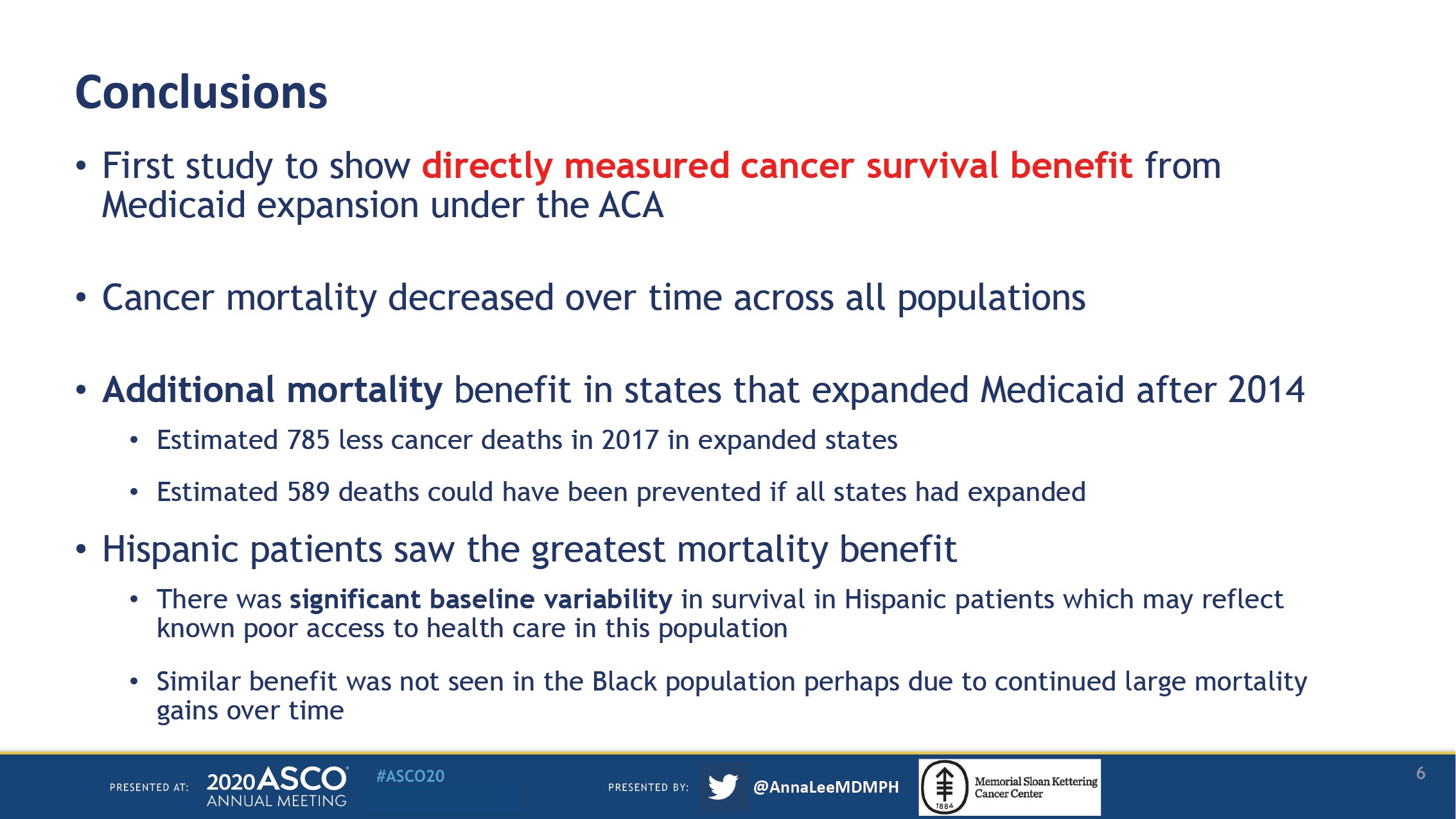

What Lee and Chino found was staggering: a 29% decline in age-adjusted overall cancer mortality rates in states with expanded Medicaid, falling from 65.1 to 46.3 per 100,000 individuals, from 1999 to 2017.

By comparison, in states that did not expand Medicaid, rates dropped by 25%, from 69.5 to 52.3 per 100,000 individuals.

“Health insurance matters. The simple action of facilitating people to get health care has really made a difference,” Chino, senior author of the study and a radiation oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, said to The Cancer Letter. “Previous work has shown that gains in insurance have led to earlier stages of diagnosis, timelier treatment, improved access to treatment. All of those things matter and ultimately lead to survival benefit.”

The data show persistent health disparities in communities that have historically seen the worst outcomes. While Hispanic populations experienced the greatest decline in cancer mortality, no additional reduction was seen for black patients in states with Medicaid expansion—despite large mortality gains over the study period (The Cancer Letter, Feb. 7, 2020).

“Black populations were continuing to have large improvements in mortality over time, this may have washed out any benefit from the ACA, but it’s still not enough to eliminate disparities,” Lee, lead author of the study and a proton therapy fellow at MSK, said to The Cancer Letter. “Black patients had such worse baseline cancer outcomes that the peri-ACA years were catch-up years. It’s clear we still have a ways to go to improve healthcare disparities in this population.”

Cancer is a “health care amendable” condition, where access to health care is expected to improve outcomes, the researchers said. About 20 million people gained insurance under the Affordable Care Act.

The study was conducted using data from the National Center for Health Statistics, which includes all U.S. residents. After assessing for baseline trends from 1999 to 2017, the researchers compared age-adjusted cancer-related mortality rates between 2011 to 2013 (prior to full state expansion) and 2015 to 2017 (the period following expansion) for states that adopted Medicaid expansion and states that did not.

Deaths due to cancer in patients under the age of 65 were included in the analysis, as patients 65 and older are eligible for Medicare. During the time period of this analysis, 27 states plus the District of Columbia had adopted Medicaid expansion, while 23 states had not.

The Lee et al. study was placed at the top of this year’s scientific program highlights at the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s virtual annual meeting.

“The overall age-adjusted cancer mortality was consistently worse in NonEXP states, cancer mortality fell from 64.7 to 46.0 per 100,000 in EXP states and from 69.0 to 51.9 per 100,000 in NonEXP states from 1999-2017 (both trends p < 0.001, comparison p < 0.001),” the abstract states.

In 2019, a study by Adamson et al., which received similar attention, found that Medicaid expansion is associated with a 4% reduction in post-diagnosis time to treatment for black patients with metastatic cancer—effectively a near-elimination of racial disparities in timely treatment in states with Medicaid expansion (The Cancer Letter, June 21, 2019).

“I don’t think that Medicaid insurance is a magical insurance, and there are certainly many flaws within the ACA,” Chino said. “However, when we think about how to improve the overall healthcare status of the United States, a lot of the provisions that were put in place in the Affordable Care Act can be seen paying fruit now.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has once again put a spotlight on racial disparities and the dearth of public health care in the U.S. In Washington, D.C., for example, 80% of those who died from COVID-19 and whose deaths are listed on the D.C. Department of Health website are identified as African American. A similar pattern has been observed throughout the D.C.-Maryland-Virginia region, as well as across the country (The Cancer Letter, May 8, 2020).

“We’re seeing, in this COVID-19 pandemic, that there are large healthcare disparities in the U.S., and that the pandemic is disproportionately impacting and killing people of color and of lower socioeconomic status,” Lee said. “So, it is vital that we improve access to health care so that everyone has an equitable chance of surviving.”

Lee received her MD from Mercer University in Macon, GA, where she attended to patients with cancer, whose lives, she said, may have been saved if they were covered by Medicaid or some form of health insurance. Georgia is a non-expansion state.

“I saw first-hand during my time on the wards as a medical student, patients who came in who had no insurance for very preventable cancers, like breast cancer,” Lee said. “So, they didn’t have a screening mammogram, presented with stage IV metastatic breast cancer, and died within a couple of months. And I think that that could have been preventable if they had health insurance.”

Chino’s academic research is informed by her lived experiences: her husband died from neuroendocrine carcinoma in 2007. He was a PhD candidate at Rice university, and his student insurance didn’t cover much—she was left with debt that is estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

“I’m very passionate about this, because the level of financial toxicity that my family went through with my husband’s treatment was extreme, and it would not have happened under the Affordable Care Act,” Chino said.

“The next steps in terms of additional evaluation of the benefit of the Affordable Care Act, I am interested in looking to see how, for example, health insurance patterns have changed after the Trump administration came in. There was, at least based on national trends, unfortunately, a reversal of health insurance patterns with more and more people actually becoming uninsured again.”

Other authors on this study are: Kanan Shah at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, and Junzo P. Chino at Duke University Medical Center.

Lee and Chino spoke with Matthew Ong, associate editor of The Cancer Letter.

Matthew Ong: What are the major takeaways from your study?

Anna Lee: The major takeaway was that we found an additional cancer mortality decrease in states that adopted Medicaid expansion in 2014. We also found that baseline cancer mortality rates are better in ACA expansion states and in all subpopulations within expansion states.

Some other findings observed support prior research, namely, that cancer mortality is falling for everyone and that disparities exist between groups—such as higher cancer mortality noted in the black population.

Fumiko Chino: Health insurance matters. The simple action of facilitating people to get health care has really made a difference. Previous work has shown that gains in insurance have led to earlier stages of diagnosis, timelier treatment, improved access to treatment. All of those things matter and ultimately lead to survival benefit.

It’s not something that’s realized in a year or two years. I think it’s something that will continue to develop, and we may be able to show potentially even larger benefits with even longer followup data.

Dr. Lee, while baseline cancer mortality rates are better in Medicaid expansion states, black patients appear not to be experiencing the benefits. What’s happening here, and what can you infer from the data?

AL: Black populations were continuing to have large improvements in mortality over time, this may have washed out any benefit from the ACA, but it’s still not enough to eliminate disparities.

Black patients had such worse baseline cancer outcomes that the peri-ACA years were catch-up years. It’s clear we still have a ways to go to improve healthcare disparities in this population.

Your study is described as the first nationwide study of its kind. What have you done that is different from what others have done?

AL: Prior studies have assessed the changes the ACA has made on insurance status, cancer stage, or timely and appropriate access to cancer treatments—those are the first measurable changes after a large national health policy initiative like the ACA.

The translation of those benefits into an actual cancer mortality decrease can take years. This is likely why no prior study has been able to show this benefit from Medicaid expansion. Our study team has been following cancer mortality changes for many years, we saw some early changes, but were not able to show the definitive benefit until now.

FC: I’m very passionate about access, delivery of care, and affordability. So, this has been something that I’ve been researching for a couple of years now. I think one of the benefits of our study is that it’s data source is truly comprehensive and includes all cancer deaths nationwide—it really allows us to show, in real cancer lives, how insurance matters.

Our groups’ previous work showed decreases in uninsurance for patients receiving radiation treatment for newly diagnosed cancers. The current study is the culmination of prior work—basically, if you make all of these incremental improvements, it ultimately leads to saving lives.

In the data, did you observe greater decreases in cancer mortality for specific cancers?

AL: We looked at overall age-adjusted cancer specific mortality, but what you are asking about is correct in that we think the ACA may have had more of an impact for certain cancers over others. So, this is something that we are looking at now.

The hypothesis, obviously, is that patients with certain types of cancers that divide quicker may be the ones to benefit the most for gaining insurance. I think when you’re trying to document a survival benefit, though, sadly it really is large numbers which allow you to show that.

And so, we may not be able to show that survival benefit for certain types of cancers yet. That may require even more years of follow up just based on, again, the volume. There’s 600,000 people who die of cancer every year in the United States, but there’s a much lower percentage of certain types of cancers.

Could you describe why your study is especially important in our current social and political climate? And are there any aspects of your personal life or upbringing that give you a unique perspective that you bring to conversations on healthcare disparities?

AL: Yes, I think we’re seeing, in this COVID-19 pandemic, that there are large healthcare disparities in the U.S., and that the pandemic is disproportionately impacting and killing people of color and of lower socioeconomic status. So, it is vital that we improve access to health care so that everyone has an equitable chance of surviving.

There are shifting environments with regard to the ACA. Many of the provisions that were put in place have eroded in the past couple of years, so this could erode the benefit of what our study shows.

And personally, I am from a non-expansion state of Georgia, and I went to medical school there. I saw first-hand during my time on the wards as a medical student, patients who came in who had no insurance for very preventable cancers, like breast cancer. So, they didn’t have a screening mammogram, presented with stage IV metastatic breast cancer, and died within a couple of months. And I think that that could have been preventable if they had health insurance.

FC: Unfortunately, I was personally affected by one of the health care plans that were available before the Affordable Care Act—without all of the protections that were put in place with Obamacare in terms of, for example, caps or restrictions on services provided.

And so, I’m very familiar with the idea that when the Affordable Care Act passed, that it not just gave people insurance through Medicaid, but it also actually improved the standard for all health insurance plans, even for non-Medicaid plans.

I’m very passionate about this, because the level of financial toxicity that my family went through with my husband’s treatment was extreme, and it would not have happened under the Affordable Care Act. So, honestly, I’m personally very vested in this.

You’ve talked about this, but what would you say are some of the specific implications of your study, not only for health policy broadly, but also for underserved communities in an era of pandemics?

AL: Poor access to health care continues to be a problem. There was a recent study that showed that patients living in certain areas had less access to testing for COVID-19. Likewise, we know that patients who have poor access are more likely to present at advanced stages of cancer. They’re less likely to receive curative treatments like surgery, radiation, less supportive care. So, this work highlights the importance of health care, and that inadequate access can be a life or death matter.

FC: I will just add to that to say that some of the places in the United States that are really struggling, for example, rural communities. I think the data has really shown that they could be benefited by Medicaid expansion, because it may actually help some of those rural hospitals stay open; and then help actually provide enhanced or better access to those patients.

I don’t think that Medicaid insurance is a magical insurance, and there are certainly many flaws within the ACA. However, when we think about how to improve the overall healthcare status of the United States, a lot of the provisions that were put in place in the Affordable Care Act can be seen paying fruit now.

It’s noteworthy, also, that Hispanics in expansion states experienced higher differential cancer mortality benefit. Do you have any thoughts as to why this was the case?

AL: There were more Hispanic patients that were living in the expanded states, compared to non-expanded states. And this group does have a highest baseline uninsurance rate. So, perhaps they did have the most to gain from Medicaid expansion. But also, we want to be very clear that in our data, there was a lot more variation year-to-year in the Hispanic population.

And so, this variability may be a reason why we detected a cancer mortality benefit, but we need better long-term data to be sure, to show a definitive benefit.

Is there anything else that you would like to highlight?

FC: I was just encouraged by all of the fantastic conversation that happened during the ASCO virtual meeting about our study and about a lot of the other projects that were presented. There were many studies that were designed to try to level the playing field, to try to improve access for patients, designed to meet patients where they are.

There’s been a real movement to design interventions that can provide the best care for patients, wherever they’re coming from. And that was just really exciting for me.

What are your next steps for this study?

AL: So, right now, we’re looking at, like we mentioned before, cancer-specific mortality from specific subtypes. We think certain cancers that divide quicker—like head and neck cancer, which is the area of my interest, and cervical cancer, which is Dr. Chino’s interest—patients who have these types of cancers may benefit more from Medicaid expansion, having timely access to health care through health insurance.

I think the fact that from the time a woman finds a lump in her breast, or even from the time that she had a screening mammogram that detects a mass to getting treatment, for us to see a benefit in just a few years since Medicaid expanded was really remarkable. So, we’re excited to see, specifically, which types of cancers may be benefiting the most from Medicaid expansion.

What are some of the other projects that the both of you are currently working on, or other research questions that you’d like to pursue in the future?

FC: My major focus, in addition to access to care and healthcare disparities is cancer care affordability, which I think you can understand, they are all interrelated.

I’m at Memorial Sloan Kettering, we’re currently working on designing interventions that are both patient-facing and provider-facing, to truly try to tackle the idea of cancer treatment affordability from many different angles. Because, I think we can all agree that—for some patients, not everyone— cancer treatment is honestly just unaffordable and that there are many steps along the way at which you could intervene to really make a meaningful difference in terms of the costs of care.

And then, honestly, the next steps in terms of additional evaluation of the benefit of the Affordable Care Act, I am interested in looking to see how, for example, health insurance patterns have changed after the Trump administration came in. There was, at least based on national trends, unfortunately, a reversal of health insurance patterns with more and more people actually becoming uninsured again.

Health insurance matters. The simple action of facilitating people to get health care has really made a difference. Previous work has shown that gains in insurance have led to earlier stages of diagnosis, timelier treatment, improved access to treatment.

Fumiko L. Chino

For our study, of course, that’s concerning because that could potentially erode the benefit of what we’ve seen in terms of overall survival. It’s important to show that patients with newly diagnosed cancers either do or do not have health insurance, because the insurance that you had at diagnosis is often instrumental to you actually getting that diagnosis, and then starting timely treatment. And so, not having insurance really can delay a lot of steps along that way.

Even though emergency Medicaid is available in certain states for certain cancers, that’s potentially an additional delay. And so, in terms of going back to see, well, we showed that people gained health insurance, and now we’ve shown that there’s been a mortality benefit. Are we going to see the reverse happening? That people are now not having health insurance and, ultimately, have negative downstream cancer outcomes?

AL: Well, I am completing a proton therapy fellowship right now, and we know that certain types of treatments are more expensive. And so, one that Dr. Chino and I hope to look at in the future is patients trying to garner funds on public fundraising platforms for specific types of treatment, like proton therapy.

I’ve seen and helped treat a lot of patients with proton therapy and this is one type of treatment modality that I’m interested in as I see the potential benefit. But also, I also want to make sure that it’s affordable and accessible for patients and trying to ascertain, what are patients doing to try to get this sort of treatment?

Thank you for making the time to talk to me.