A growing number of women forgoing reconstruction after a mastectomy say they’re satisfied with their choice, even as some did not feel supported by their physician, according to a study led by researchers at the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center.

The study, published in Annals of Surgical Oncology, surveyed 931 women who had a unilateral or bilateral mastectomy without current breast mound reconstruction to assess the motivating factors for forgoing the procedure and to measure whether surgeons provided adequate information and support for “going flat.”

Out of the women surveyed, 74% were satisfied with their outcome and 22% experienced “flat denial,” where the procedure was not initially offered, the surgeon did not support the patient decision, or intentionally left additional skin in case the patient changed her mind.

The team also explored reasons given for the choice and found women pointed to a desire for a faster recovery, avoidance of a foreign body placement and the belief that breast mound reconstruction was not important for their body image.

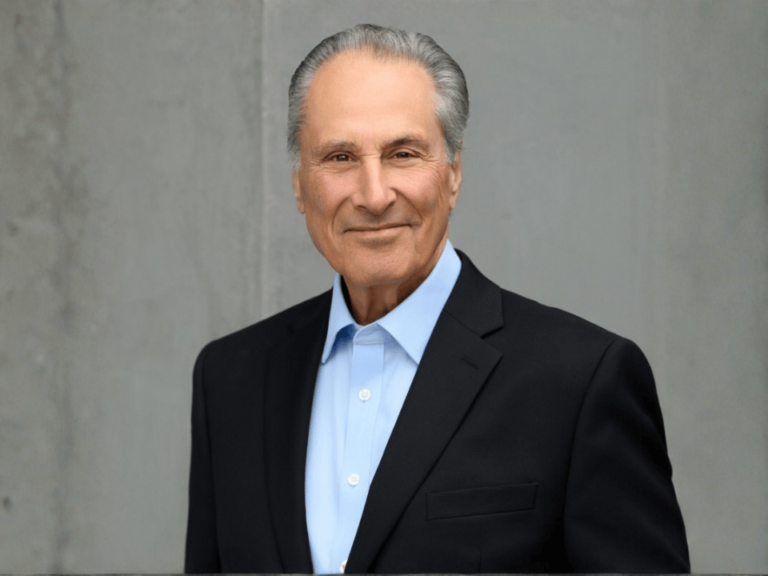

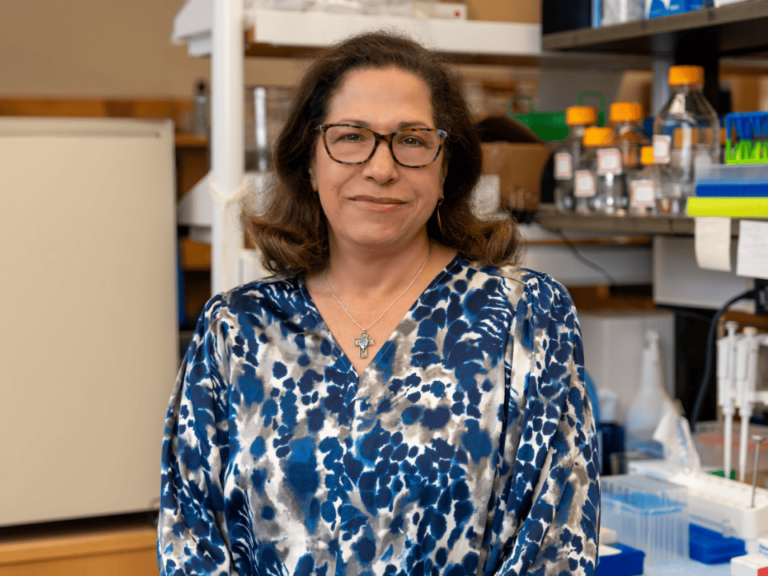

“Undergoing a mastectomy with or without reconstruction is often a very personal choice,” senior author Deanna Attai, an assistant clinical professor of surgery at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, said in a statement. “We found that for a subset of women, ‘going flat’ is a desired and intentional option, which should be supported by the treatment team and should not imply that women who forgo reconstruction are not concerned with their postoperative appearance.”

The results challenge past studies showing that patients who chose not to undergo breast reconstruction tend to have a poorer quality of life compared with those who do have the surgery.

Attai and her team found that a majority of patients who elected to go flat were in fact satisfied with their surgical outcome. The authors believe that the survey tool commonly used for assessing outcomes was biased towards reconstruction. To avoid that bias, Attai partnered with patient advocates to develop a unique survey to assess reasons for going flat, satisfaction with their decision, and factors associated with satisfaction. They also identified concerns unique to these patients not captured by other validated surveys.

While a majority of the women surveyed reported they were satisfied with their surgical outcomes, 27% of patients surveyed reported not being satisfied with the appearance of their chest wall.

“Some patients were told that excess skin was intentionally left—despite a preoperative agreement to perform a flat chest wall closure—for use in future reconstruction, in case the patient changed her mind,” said Attai, who is also a member of the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center. “We were surprised that some women had to struggle to receive the procedure that they desired.”

Surgeons may hesitate to recommend mastectomy without reconstruction surgeons due to being less confident that they can provide a cosmetically acceptable result for patients who desire a flat chest wall, she said.

“We hope that the results of this study will serve to inform general and breast surgeons that going flat is a valid option for patients, and one that needs to be offered as an option,” said Attai. “We also hope the results may help inform patients that going flat is an option, and to empower them to seek out surgeons who offer this option and respect their decision.”