Earlier this week, the Senate Committee on Finance convened what is likely to be the first in a series of hearings focused on the rising costs of prescription drugs, oncology drugs among them.

“This hearing is not a one-off,” Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR), the committee’s ranking member, said at the hearing Jan. 29. “This is the first in a series we will hold on this topic. So, nobody is going away, and even if it means using our power to compel the drug company CEOs to show up, they will come before this committee. The crisis of prescription drug costs threatens too many lives and bankrupts too many people for the Congress to tolerate this ducking and weaving by the companies that caused it.”

Several pharmaceutical companies were invited to testify—two said they would show up, but none were seen at the Dirksen Senate Office Building on the day of the hearing.

“I want to express my displeasure at the lack of cooperation from the pharmaceutical manufacturers recently,” said Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-IA), the committee’s chair, who, like Wyden, is known for his penchant for political theater. “The companies that declined said they would discuss their ideas in private, but not in public. One company mentioned that testifying before the committee would create a language barrier problem. That is not what I mean when I talk about transparency.”

The drug industry lobbying association PhRMA declined to comment. Biotechnology Innovation Organization, another trade association, didn’t respond to an email from The Cancer Letter.

At the hearing, Wyden said he plans to take a closer look at why drug manufacturers have “unchecked power” when setting prices.

“I’m especially troubled by health care middlemen who skim off enormous sums of money, when there’s scant evidence they’re getting patients a better deal,” Wyden said. “That sure looks like it’s the case with pharmacy benefit managers. Called PBMs, they’re supposed to negotiate better deals, but the reality is, they take a big cut and inflate list prices.”

Early in his career, Wyden, then a House member, challenged the pricing of Bristol-Myers Squibb drug Taxol (paclitaxel), arguing that the drug, developed through a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement with NCI, had enabled the company to, as he put it, “price gouge.”

Wyden’s efforts resulted in a “reasonable pricing clause” for drugs developed through collaboration between NIH and pharmaceutical companies.

The clause was ultimately removed from NIH reauthorization, as companies complained that working with government researchers had become unsustainable. Wyden has famously made tobacco executives testify under oath about the link between tobacco and cancer. Similarly, he made oil company executives testify on the link between fossil fuels and global warming. It’s unlikely in the extreme that pharma executives want to play part in a similar show.

The prices of cancer drugs are increasing at an unsustainable rate, Peter Bach, director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, said in his testimony at the hearing. Bach runs the Drug Pricing Lab, which is funded by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, Kaiser Permanente, and MSK.

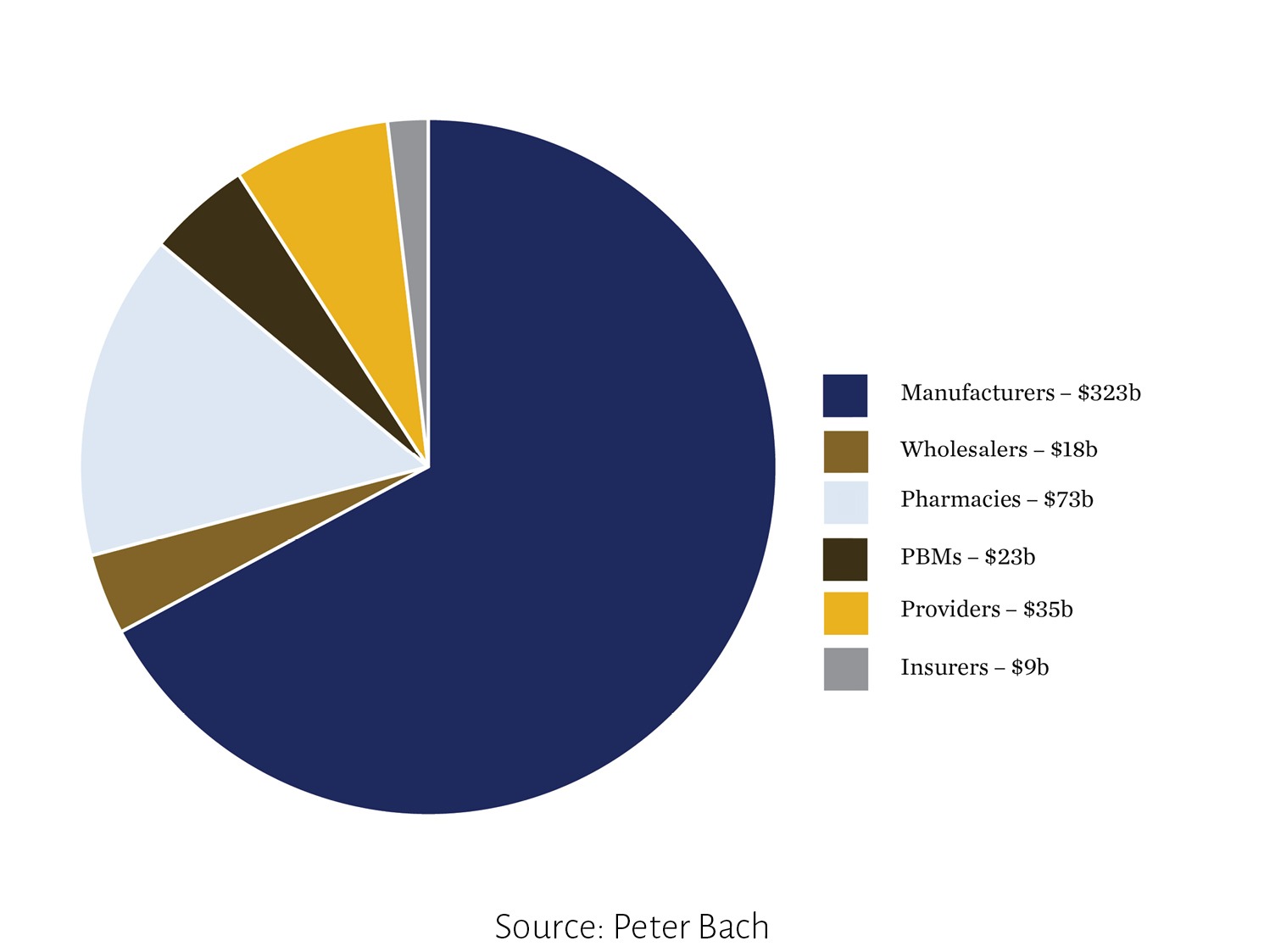

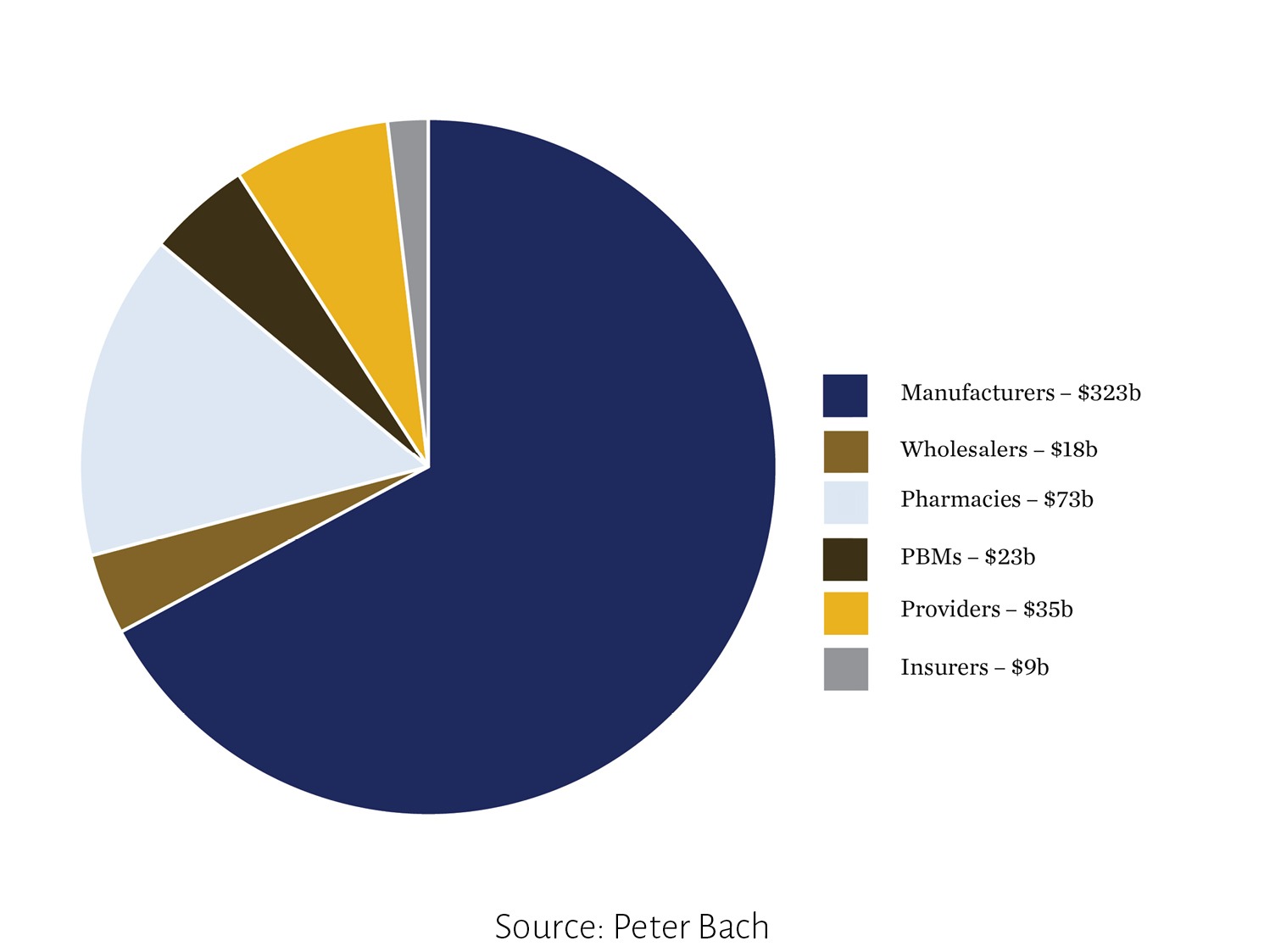

The largest share of pharmaceutical product revenues goes to drug manufacturers, Bach testified. In 2016, out of $500 billion in total spending, $323 billion—about two-thirds—went to industry, Bach said. The rest of the revenues were retained by wholesalers, pharmacies, PBMs, providers, and insurers. The text of Bach’s study is posted here.

“An organizing theme of the pharmaceutical supply chain is that all participants benefit as both drug prices and total spending rise,” Bach said. “Pharmaceutical corporations logically seek to profit by charging high prices, but ideally the other parties in the supply chain would serve as a countervailing force to push prices down.

“Pharmaceutical products are often marked up in percentage terms as they pass through the supply chain,” Bach said. “This means that more expensive drugs on average bring larger profits. This pattern applies to wholesalers and pharmacies. It also applies to physicians and hospitals when they use expensive infused drugs covered by Medicare Part B. This is because the reimbursement formula for Part B drugs includes a mark-up over the average acquisition price of the drug.”

Bach’s full testimony can be found here.

As a result, physicians are significantly more likely to mark up prices, Bach’s study shows.

“We recently reviewed studies that examine whether or not the profit potential for various [Medicare] Part B drugs influences prescribing; across the studies we examined, the conclusion was consistent that they do,” Bach said. “On the margin, physicians will prescribe the more profitable of drugs when there are options to choose from. Aaron Mitchell and colleagues published a review of this topic as well. [These] authors graded the quality of the literature along with summarizing its findings and arrived at the same conclusion. Physicians systematically select more profitable drugs to prescribe when they are able to choose among clinically substitutable options.”

This preference was also noted in hospital outpatient departments.

“My team conducted an analysis that showed that among treatments in oncology that are not recommended and that involve expensive Part B drugs, the likelihood that these treatments were administered was higher in physician offices than hospital outpatient departments across all the clinical scenarios we examined, a finding that was robust to clinical severity risk adjustment.” Bach said.

Douglas Holtz-Eakin, president of American Action Forum, said debates on drug pricing should focus on the “high-value,” not “low cost” of drugs.

“Particularly with oncology drugs, it is important to make sure that the cost of the treatments correlates to the value,” Holtz-Eakin said at the hearing. “Remember that the goal is not low cost, it is high value. It is easy to have low-cost drugs; they, however, may not do much good. Conversely, it might make sense to spend more for a drug if its therapeutic benefits are high enough.”

The American Action Forum is an affiliate of American Action Network, which, according to its website, is an “’action tank’ that will create, encourage and promote center-right policies based on the principles of freedom, limited government, American exceptionalism, and strong national security. The American Action Network’s primary goal is to put our center-right ideas into action by engaging the hearts and minds of the American people and spurring them into active participation in our democracy.”

Policymakers should first identify the “actual problem” in the debate on drug pricing, Holtz-Eakin said.

“There is little consensus in the term ‘rising drug costs,’ making it difficult to determine if there is an actual policy problem, its size, or its scope,” Holtz-Eakin said. “Rising drug costs could also mean an increase in overall prescription drug expenditures, whether in dollar figures or as a percentage of National Health Expenditures,” Holtz-Eakin said. “Because spending is a function of both price and quantity, this could result from increased utilization due to rising national reliance on prescription drugs or broader access to them.”

The long-term financing of cures is the industry’s way of framing the issue backwards, with the goal of protecting their revenues, Bach said.

“’Value-based pricing’ has been proposed by a number of analysts for new branded drugs with no competition,” he said. “Today we often end up with drugs priced at levels well beyond what their benefits justify. We then see payers attempt to counteract these high prices. Payers insert barriers to access including shifting costs to out of pocket, delaying access through utilization management, and generally thinning the quality of the insurance benefit for patients who most need insurance.”

In cases where pharmaceutical companies are able to extend drug patents and prevent generic versions from entering the market, they have monopoly over drug prices.

“When companies say we need to change our payment system to afford their new high- priced treatments, they are framing the issue backwards,” he said. “Prices for monopoly goods are dictated primarily by what payers are willing to pay for them, as the companies do not face traditional market competition that would put downward pressure on their prices.

Pharmaceutical corporations logically seek to profit by charging high prices, but ideally the other parties in the supply chain would serve as a countervailing force to push prices down.

Peter Bach

“So, when companies call for long term financing to pay them for their treatments, they are inventing a means by which the market can pay them more than they would get without such a system. But in viewing this proposal, it is important to keep in mind that these drugs do not inherently cost $1 million or $2 million dollars. Rather, it is policy choices that will dictate what they cost, policy should not configure to what the corporations want them to cost.”

Bach proposed what he refers to as “The Netflix Model,” which would allow states to procure highly priced Hepatitis C medication at a flat subscription payment over a set number of years.

Mark Miller, executive vice president of health care at the Arnold Ventures, previously known as the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, said the “virtuous cycle” of pharmaceutical companies maintains these monopolies.

“Instead of encouraging research into the next generation of cures, firms with drugs approved by the FDA are incentivized to hold on to their monopolies as long as possible and deploy as many anti-competitive tactics as possible to ensure generics or biosimilars are not available,” Miller said.

“Of the roughly 100 best selling drugs, nearly 80 percent obtained an additional patent to extend their monopoly period at least once,” he said. “Nearly 50 percent extended it more than once. For the 12 top selling drugs in the United States, manufacturers filed, on average, 125 patent applications and were granted 71. For these same drugs, invoice prices have increased by 68 percent.”