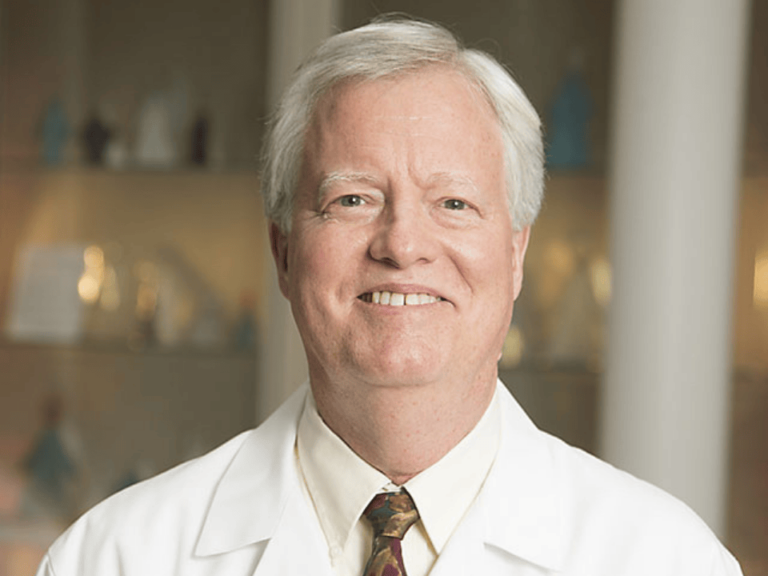

Over his five decades as a radiation oncologist, Bernie Lewinsky has been collecting the relics of radiotherapy.

When he joined California Hospital Medical Center, he jumped at the opportunity to rummage through an old forgotten box of film tins that the hospital was storing. He found footage from 1938.

The treasures in the box included a film of Marie Curie receiving the first gold medal from the American College of Radiology in Paris.

“I opened it up and I burnt my eyes with the methane from the film,” said Lewinsky, who has since converted the film to DVD. “This needs to go to the ACR or ASTRO. This is going to be destroyed by somebody who doesn’t know.”

Lewinsky brought a treasure trove of artifacts to a recent oral history interview with Stacy Wentworth, fellow radiation oncologist at Duke University School of Medicine, who hosted this episode of the Cancer History Project Podcast.

During the interview, Lewinsky set up a show-and-tell, pulling out the radiotherapy devices of the past: written orders of radium needles from 1948, an attachment that connected to an orthovoltage machine, a Mick applicator, and even a Bunsen burner.

“Now it’s so much more accurate, so much different and so precise,” Lewinsky said. “When you start talking about blocking the nodes in the heart to stop arrhythmias, we’re very specific.”

This episode is available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and YouTube.

Lewinsky developed the first group of freestanding radiation therapy clinics in Los Angeles, CA. He was also one of the co-founders of the Endocurietherapy Society, which now exists as the American Brachytherapy Society.

He began his training in the early 1970s and was influenced by some of the radiation oncology greats.

His mentors, Jerry Vaith and Walter Gunn, trained directly under pioneers of the field, including Juan A. del Regato: “the big father of American radiotherapy.” During residency, a rotation at the Royal Marsden Hospital in London made Lewinsky one of the final residents trained by Sir David Waldron Smithers, another pioneer in radiotherapy and a widely respected clinician. He also learned from H.J.G. Bloom, who developed the Bloom-Richardson classification for breast cancer, on that rotation.

Throughout his career, Lewinsky has seen radiation therapy transform.

“You’ve gone from a betatron, cobalt and radium needles, and treating AP [Anterior-Posterior radiation] one day and PA [Posterior-Anterior radiation] the next, to probably treating on some sort of amazing [technology like a] TrueBeam or Elekta,” Wentworth said, summarizing the podcast.

Lewinsky is a practitioner of the arts, as well as the sciences. His passion for landscape photography started when he was a child growing up in El Salvador. “When I was a boy, I was just fascinated by the active volcano that we had and I started photographing at age eight,” he said.

Following the remodel of his Los Angeles clinic—and an impulse decision to hang a print on the wall of one of his photographs of cherry blossoms—Lewinsky saw the profound impact that overlapping his two passions could have on the patient experience.

Photograph by Bernie Lewinsky.

Photograph by Bernie Lewinsky.

Kings Canyon National Park, CA.

Black and white silver print photograph

by Bernie Lewinsky.

Said Lewinksy:

I said, “Oh, that cherry blossom might look good in there.” Printed it, pasted up there.

One day, I saw a patient with prostate cancer, Latino guy, and he just sat there, mesmerized and the wife said, “Hey, the doctor doesn’t have all day. Pay attention to him.” I said, “Wait a minute, let me ask him, what is it about that picture that’s got you mesmerized?” And he says, “I remember when I was a little kid, my dad would take us cherry-picking and I sure wish my dad was here right now.”

Later, Lewinsky worked with the architect of Vantage Oncology’s West Hills facility to develop floor-to-ceiling displays that immerse patients in nature, as if they’re sitting on a pile of rocks at the bottom of a cascading waterfall.

“I had patients that were upset that their treatment finished because the half an hour of waiting was the time that they could sit and relax and just calm,” Lewinsky said.

A new Women’s Center at California Hospital Medical Center will include a courtyard called the Dr. Lewinsky’s Healing Garden, he said.

Read more on the Cancer History Project. This interview is available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and YouTube.

Related Articles

- Melvin J. Silverstein on DCIS, breast cancer surgery, and building the first free-standing breast center, June 2, 2025

Melvin J. Silverstein, now Medical Director of Hoag Breast Center and the Gross Family Foundation Endowed Chair in Oncoplastic Breast Surgery at USC, sat down with Stacy Wentworth, radiation oncologist and medical historian, to reflect on his career.

Silverstein founded the Van Nuys Breast Center in 1979. As he saw more and more and more patients with what was only recently coming to be known as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), he wrote the first major textbook on the disease and developed the Van Nuys Classification for Ductal Carcinoma in Situ of the Breast as well as the USC Van Nuys Prognostic Index.

“I became wildly passionate about DCIS. I thought about it all the time,” Silverstein said. “I thought about it when I went to sleep.”

- Weeks before death from sarcoma, Norm Coleman reflects on career in radiation oncology, addressing health disparities, March 22, 2024

Soon after he was diagnosed with a dedifferentiated liposarcoma, C. Norman Coleman reached out to The Cancer Letter and the Cancer History Project to initiate a series of interviews about his life and career.

“I don’t know how much time I have,” Norm said during the first interview.

The plan was to keep going for as long as possible. Alas, only one interview—about an hour’s worth—got done.

Coleman died March 1 at 79 (The Cancer Letter, March 8, 2024).

Colleagues say Coleman was working on a manuscript two days before he died.

At NCI, Coleman was the associate director of the Radiation Research Program, senior investigator in the Radiation Oncology Branch in the Center for Cancer Research, and leader of a research laboratory at NIH.

He was also the founder of the International Cancer Expert Corps, a non-profit he created to provide mentorship to cancer professionals in low- and middle-income countries and in regions with indigenous populations in upper-income countries.

Coleman spoke with Otis Brawley and Paul Goldberg, co-editors of the Cancer History Project. Brawley is the Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Oncology and Epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, and Goldberg is the editor and publisher of The Cancer Letter.

The Cancer History Project is a free, collaborative archive of oncology history that aims to engage the scientific community and the general public in a dialogue on progress in cancer research and discovery.

This project is made possible with the support of our sponsors: the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, ACT for NIH, UK Markey Cancer Center, Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey/RWJBarnabas Health, The University of Kansas Cancer Center, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

The Cancer History Project is an initiative of The Cancer Letter, and is backed by 60 partners, spanning academic cancer centers, government agencies, advocacy groups, professional societies, and more.

Interested in learning more about the history of oncology? Subscribe to our monthly podcast on Spotify or Apple Podcasts.