The Cancer History Project is highlighting survivor stories throughout the month of June, which we jumpstarted with interviews conducted by guest editor Deborah Doroshow, assistant professor of medicine at Tisch Cancer Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

The following are survivor stories contributed by Fox Chase Cancer Center, the University of Kansas Cancer Center, and Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center. Read more survivor stories here.

- Rob Krigel: Oncologist Turned Patient

By Fox Chase Cancer Center | July 8, 2021

In 1984, Rob Krigel came to Fox Chase Cancer Center as director of the Department of Hematology. During his time at Fox Chase, Krigel conducted groundbreaking work on early clinical trials of combination therapies for the treatment of cancer, as well as interferon research.

But Krigel had already made a name for himself at New York University, where he had trained as a hematologist and oncologist prior to joining the staff there. His time at NYU coincided with the beginnings of the AIDS epidemic, and Krigel became a leading authority on the management of AIDS-related malignancies.

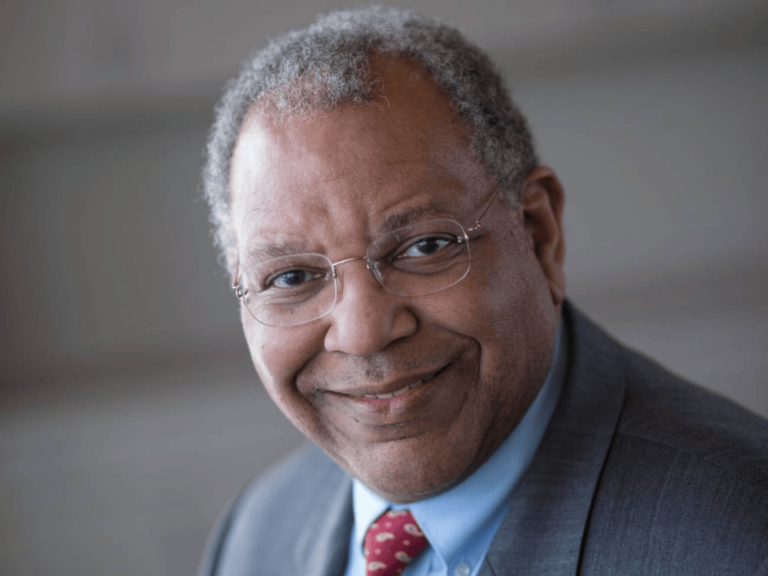

After leaving NYU, Krigel found his second family at Fox Chase, where he became known for the great compassion he showed his patients and their families. “He was beloved and a symbol of the special character of the institution,” said Lou Weiner, an oncologist and former colleague at Fox Chase who later became Krigel’s best friend. Weiner is now director of the Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center in Washington, D.C.

Although the two had attended the same undergraduate and medical schools, they had never crossed paths before coming to Fox Chase. But they became close, rooming together at medical conferences, going on family vacations together, almost like brothers.

Krigel also helped train the next generation of oncologists, people like Lori Goldstein, a professor of hematology and oncology at Fox Chase. “He made us better, more caring people and physicians,” said Goldstein.

In 1993, Krigel left Fox Chase to become director of the Lankenau Cancer Research Institute in Wynnewood, PA. After being at Lankenau for about six months, Krigel called Weiner in the middle of the night because he thought he had perforated an ulcer.

Weiner, who was the attending medical oncologist at Fox Chase, reviewed the X-rays and later bloodwork showed that Krigel had cancer, angiosarcoma that had spread through his body and had previously shown no symptoms. “I had to go in at the moment we made the diagnosis and tell my best friend he had cancer,” said Weiner.

He recalls Krigel insisting on seeing the X-rays himself and going down to the radiology suite in his hospital gown. “He took one look at the X-rays and knew exactly what they meant,” said Weiner. “He said, ‘Aww’ with a kind of sad and knowing tone, because he knew what was going to happen.” Krigel then insisted that Weiner be his physician.

Bonnie Perlmutter, Krigel’s wife, remembered that despite the hardship of his treatment, being at Fox Chase made it easier. “You could just see it in his eyes and how he walked down the hallway. He loved it there and they loved him.”

Krigel died on April 24, 1994. He was 44.

- Nedra Bonds: Breast Cancer Survivor Learns the Art of Healing

By The University of Kansas Cancer Center | May 10, 2021

For Nedra Bonds, a cancer diagnosis was never part of the plan. But then again, the Kansas City artist, educator and community activist is pretty good at improvising.

When she was diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer—a less common and more aggressive form of breast cancer—her reaction of a simple “OK” left her physician speechless.

“I was uniquely calm. These twists and turns, they are all part of the journey,” Nedra says. “I could have cried and screamed and thrown myself on the floor, but it would not have changed anything, and I would have been behind in my planning.”

- 45 years as a Roswell Park patient: Stacey’s story

By Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center | Nov. 30, 2021

In 1977, Stacey Smith began treatment for rhabdomyosarcoma at what was then called Roswell Park Memorial Institute. At 3 years old, Stacey didn’t know or care that Roswell Park had played a pivotal role in the creation of the National Cancer Act just a few years earlier and was one of three cancer hospitals that set the model for National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers.

Rather, what Stacey remembers caring about then were the boxes of animal crackers given to pediatric patients, giggling with her favorite nurse as they playfully referred to each other as “Chicken” and getting to see the ducks in the pond that used to be on the Roswell Park grounds. She fondly remembers Dr. Daniel Green, a pioneer in pediatric oncology who treated Stacey from 1978 to 2008. And she remembers being a fighter. “It often took two or three nurses to hold me down when I was examined.”

Now, at age 47, Stacey still receives treatment at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, and from her adult perspective, she has come to appreciate so much more about how both she and Roswell Park have grown and improved over the years.

This column features the latest posts to the Cancer History Project by our growing list of contributors.

The Cancer History Project is a free, web-based, collaborative resource intended to mark the 50th anniversary of the National Cancer Act and designed to continue in perpetuity. The objective is to assemble a robust collection of historical documents and make them freely available.

Access to the Cancer History Project is open to the public at CancerHistoryProject.com. You can also follow us on Twitter at @CancerHistProj, or follow our podcast.

Is your institution a contributor to the Cancer History Project? Eligible institutions include cancer centers, advocacy groups, professional societies, pharmaceutical companies, and key organizations in oncology.

To apply to become a contributor, please contact admin@cancerhistoryproject.com.