Five academic cancer centers have formed a unique research alliance, Break Through Cancer, to focus on four cancer types—pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer, glioblastoma, and acute myelogenous leukemia.

The founding members of Break Through Cancer are Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT.

The foundation was announced Feb. 25 with a challenge pledge of $250 million from William H. Goodwin, Jr., Alice T. Goodwin, and their family, and the estate of William Hunter Goodwin III.

The challenge: to bring new approaches and new thinking as rapidly as possible to accelerate research, clinical trials, and, ultimately, cures for the deadliest cancers. The five cancer centers were chosen because they were already being supported by the Goodwin family, the foundation said.

“We realize there are no guarantees, yet we believe this effort to fight cancer, particularly with collaborative research, has a realistic probability of success,” William “Bill” Goodwin said in a statement. “We want to help people have better lives. And we sincerely hope that by being public with our support, we will inspire others to support this incredible effort.”

Hunter Goodwin, who was an investor in businesses and real estate, died of cancer on Jan. 5, 2020. He was 51. Bill Goodwin, Hunter’s father, is a Richmond businessman, philanthropist, and a principal at Riverstone group, the family’s real estate development firm. The elder Goodwin is also a former member of NCI’s National Cancer Advisory Board.

“[The Goodwin family] made the suggestion a few years ago that there might be value if we all came together, joined forces and worked together on a common set of problems, and expressed some interest in providing funding for that,” said Tyler Jacks, president of Break Through Cancer, and the David H. Koch Professor of Biology and director of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT.

“And we [the institutional leaders] took them up on that, and over the last few years have been generating what is now Break Through Cancer, a free-standing foundation, which is dedicated to changing the way that science is brought to the clinic for the benefit of cancer patients, to support teams of investigators from those five institutions and potentially others, to be bold and try to change the course of very difficult to treat cancers,” Jacks said to The Cancer Letter.

A video of The Cancer Letter‘s conversation with Jacks is posted here.

Break Through Cancer will fund and support collaborative, multidisciplinary research teams drawn from participating institutions. For its initial programs that focus on highly challenging cancer types, the foundation will rely on guidance from a scientific advisory board of experts from outside the participating institutions.

How is Break Through Cancer different from other research initiatives and consortia?

“We have five institutions, we have four diseases, that’s 20 individuals, and we’re reaching out to those individuals as individuals and as groups to begin to think together about how to pursue these problems. That is an unusual activity,” Jacks said.

“So, that is in and of itself distinctive. Getting agreement between the institutions to share information, co-analyze data, pursue clinical projects collectively, although it happens at one level, I think it will happen differently through this activity. We know that there’s great talent in each of those institutions. And at the same time, no one institution can have the best in every area.

“We have the institutional buy-in of five of the top cancer centers in the country to work together, to support the efforts of researchers in their institutions in a collaborative fashion.”

Jacks anticipates the foundation to expand its impact by partnering with broader philanthropic, biotech, and pharmaceutical companies in the future.

“We expect to raise roughly a similar amount of money over time. Imagine this being a half-a-billion-dollar effort—so, quite significant resources—which in my view are required to do what we want to do, especially in the time that we want to do it,” Jacks said. “We expect that over time, this effort will grow to include other cancer research institutions. Even now, our structures allow for teams to include investigators from an institution that is not one of those five.”

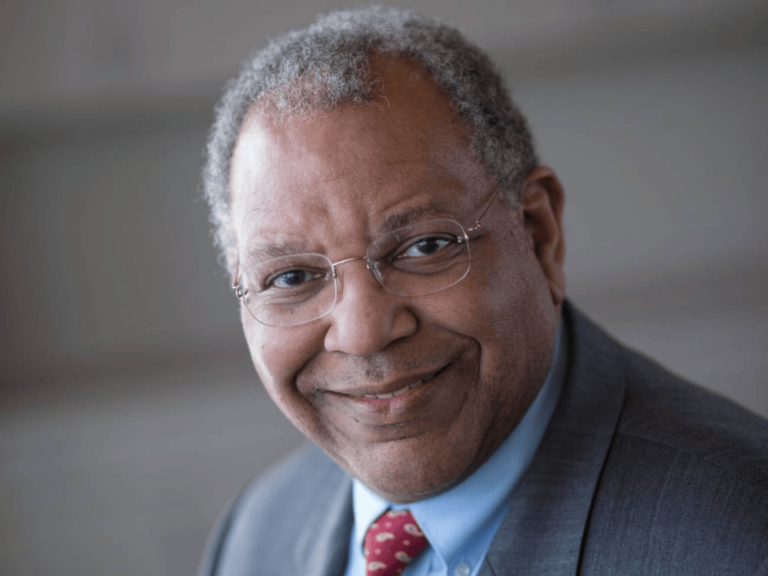

The foundation is governed by a board that includes leaders from each of the participating institutions. William Nelson, the Marion I. Knott Professor of Oncology and director of the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, serves as chairman.

“We owe a debt of gratitude to the Goodwin family and the late Hunter Goodwin, whose vision and generosity made this powerful collaboration possible,” Nelson said in a statement. “Their contributions have been key both financially and conceptually, as we worked together to create a research model that will provide a compelling advantage in the search for cures. We are fortunate to have such strong commitments from all of the parties involved.”

The membership of the scientific advisory board is not final. It doesn’t include NCI scientists as the institute is evaluating their participation for potential conflicts. The non-NCI peer review board members are:

- Cory Abate-Shen, PhD

Department of Molecular Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Columbia University - John Carpten, PhD

Professor and chair of Translational Genomics;

Director, Institute of Translational Genomics,

Royce and Mary Trotter Chair in Cancer Research, USC - Timothy Claughesy, MD

Director, Neuro-Oncology Program,

UCLA - Benjamin Haibe-Kains, PhD

Canada Research Chair in Computational Pharmacogenomics;

Senior scientist, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre;

Associate professor, University of Toronto, Department of Medical Biophysics - Patricia LoRusso, DO

Professor of medicine;

Associate cancer center director of experimental therapeutics, Yale Cancer Center - Miriam Merad, MD, PhD

Director, Precision Immunology Institute, Mount Sinai School of Medicine - Frank McCormick, PhD

Professor, Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center;

Department of Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology, UCSF - Alejandro Sweet-Cordero, MD

Director, Molecular Oncology Initiative, Benioff UCSF Professor in Children’s Health,

Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Pediatrics,

University of California, San Francisco - John Wherry, PhD

Chair, Department of Systems Pharmacology and Translational Therapeutics;

Richard and Barbara Schiffrin President’s Distinguished Professor;

Director, Institute for Immunology,

University of Pennsylvania

The members of the governing board of directors are:

- William G. Nelson V, MD, PhD

Chairman of the Board, Break Through Cancer;

Marion I. Knott Director, The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins - Lisa M. DeAngelis, MD

Physician-in-chief and chief medical officer;

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center - Giulio F. Draetta, MD, PhD

Senior vice president and chief scientific officer;

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center - Laurie H. Glimcher, MD

President and chief executive officer, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute;

Director, Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center - Alice Goodwin

Trustee,

Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research - William H. Goodwin, Jr

Trustee,

Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research - William C. Hahn, MD, PhD

Executive vice president and chief operating officer, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute;

Institute Member, Broad Institute - Susan Hockfield, PhD

President emerita,

Massachusetts Institute of Technology - Tyler Jacks, PhD

President, Break Through Cancer;

Founding director, Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, MIT - Elizabeth M. Jaffee, MD, FAACR, FACP

Cancer center deputy director and co-director, Gastrointestinal Cancers Program,

The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins - David Jaffray, PhD

Senior vice president and chief technology and digital officer,

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center - David A. Scheinberg, MD, PhD

Chair, Molecular Pharmacology Program and Director, Experimental Therapeutics Center,

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center - John Sherman

Trustee,

Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research, - David M. Livingston, MD

Charles A. Dana Chair of Human Cancer Genetics, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute;

Emil Frei III Distinguished Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School;

Special advisor to the President

Jacks spoke with Paul Goldberg, editor and publisher, and Matthew Ong, associate editor, of The Cancer Letter.

Paul Goldberg: Thanks for taking the time to talk to us, Dr. Jacks. Could you tell us more about Break Through Cancer?

Tyler Jacks: Sure. As you know, Break Through Cancer is a new foundation, which will be launching just this Thursday. It grows out of a longstanding relationship that has existed between the principal donor and family and the five institutions that represent the founding partners of Break Through Cancer.

Bill and Alice Goodwin and their children have been supporting cancer research at MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, along with Dana-Farber Harvard Cancer Center, for several years, and simultaneously Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, the Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

And they made the suggestion a few years ago that there might be value if we all came together, joined forces, and worked together on a common set of problems, and expressed some interest in providing funding for that.

And we [the institutional leaders] took them up on that, and over the last few years have been generating what is now Break Through Cancer, a free-standing foundation, which is dedicated to changing the way that science is brought to the clinic for the benefit of cancer patients, to support teams of investigators from those five institutions and potentially others, to be bold, and try to change the course of very difficult-to-treat cancers.

We are focusing on four today. They are: pancreas cancer, ovarian cancer, glioblastoma, and AML. And we are hopeful that with the ingenuity and technical capabilities that exist within those institutions, the explicit backing of the leaders of those institutions, and significant funding from the Goodwin family, that we’ll be able to make a real difference.

Matthew Ong: You talked a bit about how the institutions came together. Could you tell us more about the genesis story and how the foundation came to be?

TJ: So, as I mentioned, the Goodwin family, and here I mentioned Bill and Alice and their children, and I’ll particularly mention Hunter Goodwin, who’s now since passed away from cancer himself. That family has been very supportive of cancer research for many years, and they were doing that more on an institution-specific basis.

The idea of coming together was really from their inspiration, and when we actually did physically come together about three years ago, we actually gathered investigators from all of our institutions who were working on the four diseases I just mentioned in fact, and came together for a meeting at Kiawah Island, a resort at Kiawah Island—and spent a couple of days actually going through concepts and projects and basically new thinking about those diseases, which we might be able to make come true, were we to bring these institutions together with the right kind of resourcing.

And so, that was the beginning, that was really the genesis. And then it’s taken us now a few years to think through the specifics of that. COVID, of course, happened, and that changed our trajectory a bit.

Although, honestly, I think it’s helped us think about what urgency means. We can talk a bit about that, if you’re interested. So, that’s really how it all happened.

PG: Let’s talk about that. We’re interested.

TJ: I think it’s a fascinating subject, Paul, and I think that it’s obviously on all of our minds. And for me, at least, it falls into two relevant categories. The first is a sense of what can be done when people work together.

I think we’ve seen that in the case of the response of the scientific community, to the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers from all over the world are pooling their talents and sharing information and learning from each other with a focus on progress, as opposed to individual accomplishment. Progress, as opposed to papers, I like to say.

The reality is that the level of scientific investigation that goes along with clinical studies is usually, quite limited, such that we can’t learn from every patient. We want to change that paradigm. And then we can learn from every patient.

I love that attitude, and I’d like to see that attitude brought into cancer as well. So, that’s one thing. Collaboration is very much behind our success in the fight against this pandemic. And you guys know as well as I do, just how remarkable that has been. It’s been less than 14 months since the sequence of the virus was reported.

And now, there have been close to a billion COVID-19 tests performed in that period of time, and more than 200 million people who’ve been vaccinated against this virus; it’s just unbelievable. That could not have happened without the cooperative activity that I was referring to. That is important for us to focus on. And here I’m hearkening on my experiences with the Cancer Moonshot Initiative, the sense of urgency.

I like to say, let’s do this work like our lives depended on it. I think that’s a very important perspective—like our lives depended on it. I think the pandemic response had that quality to it, like our lives depended on it—and they do. And in cancer, of course, people’s lives do depend on it.

That’s the message that Joe Biden delivered to us as part of the Moonshot Initiative. He didn’t use those words exactly, he talked about urgency in different ways—but that sense of urgency and that sense of shared purpose. So, I think we bring that perspective and I think the experiences that we’ve had with COVID are highly influential for me and I think for all who are involved.

PG: So, to put this in a nutshell, what will Break Through Cancer do that’s not being done now?

TJ: Well, it’s a complicated answer, Paul. I think there are a lot of things that we’re going to try to do. Let’s put it that way. We have the institutional buy-in of five of the top cancer centers in the country to work together, to support the efforts of researchers in their institutions in a collaborative fashion.

Now, you might say, collaboration always happens. Sure, but it’s not always supported from the institutions themselves. We have on the board of Break Through Cancer high-level representatives from each of those five institutions. And they are actively working to make this successful.

Success will require breaking down barriers that exist within and between the institutions that we could only do with their support. Moreover, Break Through Cancer will be different by virtue of the fact that we will help organize the research effort. And that’s a distinction between this and perhaps every other version of this that I’ve been party to.

That is to say, the board of Break Through Cancer, those individuals I just mentioned—the leadership, including myself and [Jesse Boehm, PhD, scientific director of the Cancer Dependency Map and director of the Broad Cancer Model Development Center] the chief scientific officer, our scientific advisory board—will all work with investigators from those institutions to find the best ideas, form the best teams, refine those ideas, and ultimately shape the projects that get pursued and reshape them as they’re being pursued.

That’s a degree of an integrated approach to cancer research management that is unusual and something that I’m personally very committed to.

MO: How were the member institutions chosen? Why these institutions and not others? Can other institutions join?

TJ: So, the five that are founding partners were chosen because they were already being supported by the Goodwin family.

And so, they were natural fits to be part of this collective effort. They are also outstanding, so that’s another reason why they’re on the list, but there are, of course, other outstanding cancer research institutions in the country and around the world. And indeed, we expect that over time, this effort will grow to include other cancer research institutions.

Even now, our structures allow for teams to include investigators from an institution that is not one of those five. We want to be inclusive and I think this will be important to our success. Having the institutions engaged and involved will help us be successful. And doing that with five is easier than doing with 50.

PG: What’s the budget for this endeavor and how will the money be spent? Will it be in increments over a certain number of years? I noticed that this is called a challenge grant. Are you raising more money elsewhere?

TJ: Yes. So, the Goodwins have committed through a challenge, as you said, $250 million. We expect to raise roughly a similar amount of money over time. Imagine this being a half-a-billion-dollar effort—so, quite significant resources—which in my view are required to do what we want to do, especially in the time that we want to do it. Exactly how the money will be spent is still being worked out in detail.

We do expect these to be largely team-based research programs involving team members from the different institutions. So, they will be multi-investigator awards, multi-institutional awards, and some of them at least, perhaps any of them, will be quite substantial. We want to bring the best science, the best technology to patients in the context of clinical investigation. And I can talk more about what I mean by that, but this is an expensive enterprise.

These will be in many instances, multi-million dollar awards, and we’re covering four diseases at the outset, likely multiple projects for each of those diseases. And so, you can see how even that very large sum of money could be used in the next seven to 10 years, very, very effectively.

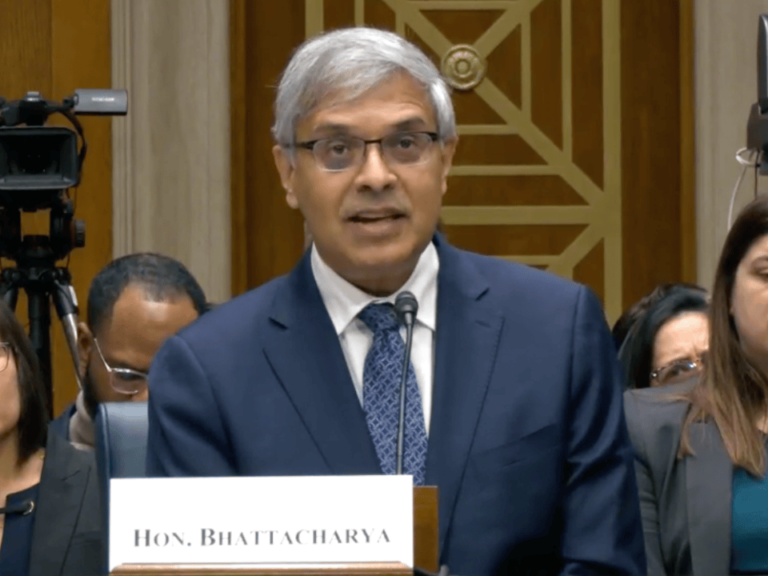

MO: And how will you ensure that there isn’t an overlap or redundancy of efforts supported by other funders, i.e. NCI? Will you be working with the NCI and the Biden administration? Will Dr. Eric Lander for instance, play a role in this?

TJ: So, obviously I know Eric Lander very well since he was my colleague at MIT. He technically still is my colleague, he’s on leave. And he is aware of what we’re doing, and I’m sure—although we haven’t talked about it in detail recently—supportive of this effort, I’m certain of it. I think that coordination at every level is very important. Of course, we want to make sure that what we are doing is not superfluous and redundant with other similar efforts.

Coordination with the NCI in particular, but not limited to the NCI, is something that we will do. I have told and engaged [NCI Director] Ned Sharpless about this for a while now, including recently. And we expect to have high-level advisors from the NCI advising us through this process.

So, to the extent that we can coordinate and avoid redundancy, we will. And at the same time, we want to empower people who are engaged with us to bring their best thinking and not feel inhibited. We’ll have to do that in a careful fashion, but yes, coordination is very important.

MO: And how does Break Through Cancer allow these well-funded institutions to do things that they could not otherwise do? They are probably a part of all kinds of consortia that already involve each other.

TJ: There are a number of existing relationships between these institutions and others, of course. And as you said, they’re well-funded institutions. So, how does this matter to them? I would say that there’s many reasons why it matters. The nature of the research organization aspect that I mentioned before, just to give you some color on that.

We have already reached out to individuals who have been nominated by their institutions to be disease leads for their institution. Each institution nominated one person to be their lead for pancreas cancer, their lead for ovarian cancer, and so forth. We have five institutions, we have four diseases, that’s 20 individuals, and we’re reaching out to those individuals as individuals and as groups to begin to think together about how to pursue these problems. That is an unusual activity.

So, that is in and of itself distinctive. Getting agreement between the institutions to share information, co-analyze data, pursue clinical projects collectively, although it happens at one level, I think it will happen differently through this activity. We know that there’s great talent in each of those institutions. And at the same time, no one institution can have the best in every area.

The collective group here has outstanding people across the wide range. Myself at MIT, I’ve got engineering colleagues in the Koch Institute, who actually bring a set of skills that really are not well located in other places. They can be brought into this picture in a seamless way through this collaboration. And that’s just one of many examples.

PG: Can we talk about peer review for a moment? Because I keep thinking about CPRIT [Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas], how that worked; and you were, of course, a very important part of that whole process. You could not really expect investigators from MD Anderson to review [CPTIT] projects that originated at UT Southwestern, for example, or Baylor, or any one of these.

So, how are you going to structure peer review? Can people from, say MIT, be on your peer review boards? Or will it be more like CPRIT, where you have non-Texas people review CPRIT grants from Texas institutions?

TJ: You’re right, I was the chair of one of those review committees—an interesting time, Paul, as you remember well. I learned a lot through that process, and, honestly, I’ve learned a lot through all these things that I’ve done over the years that have some resemblance to what we’re trying to do here.

I think outside review is essential; it gets complicated.

I’ve talked about the fact that we want to be engaged in project development and refinement and team building, but we need there to be outside eyes looking at what we’re doing and providing that perspective. So, our scientific advisory board, which consists of 11 people who come from other institutions outside of those five. And let me just add a little bit of color. And this gets to something that you asked me. Why is this different? Why is it special?

I invited 11 people to join SAB, all 11 said Yes. Partly because I know them, and I like them, and they like me. But really, when I told them about what we were trying to do, they actually completely got it and understood that it was different. It was different from other things like this that they had done.

They’re quite excited, actually, to be involved in this process of selection, as you were asking about Paul, but also monitoring progress, reshaping as we go, those projects, we know that science and clinical development is not linear. There will be things that we discover along the way that will cause us to change course and refocus our attention. So yes, the outside SAB and outside review is critical.

PG: So, the Al Gilman [founding chief scientific officer of CPRIT] approach is being used, in a way; right? (The Cancer Letter, Slamming the Door, 2016)

TJ: Absolutely. Al Gilman knew that he couldn’t have the investigators judging themselves and brought in people from outside of the state. We are bringing people from outside of these five institutions and I think it’s essential we do that.

PG: Fabulous.

MO: So, what would be the group’s first initiative? Do you have one year, five-year goals?

TJ: I think we’ll get started with one of the four diseases that I mentioned, if not more than one. I think over time, just to add to that, we likely will bring in other challenging cancers. We know there are many more than those four.

One-year goals, I want there to be teams funded, projects funded that feel and look different from what we’re used to seeing, and that the activities, those research activities are starting to manifest themselves, that the research across the institutions is actually happening.

It’s easy to talk about these things, it’s harder to do them. I want to see evidence that it’s actually happening. And over a five-year horizon, I expect some of those ideas and hypotheses and experimental approaches to yield benefits to patients. We have to be realistic about how long it takes to solve a problem like pancreas cancer.

It’s not easy for the other ones that I’ve mentioned. And yet, I do feel that with the right kind of science-driven approaches, we can really make a difference, even in that horizon. And then eventually translate that into even more meaningful outcomes for patients.

One thing I didn’t say in answer to an earlier question that I think is very poignant for me, and this was actually mentioned by one of my SAB members. He said, “We need to design something so that we learn from every patient. We learn from every patient who’s involved in this activity.”

And that may seem obvious, of course you want to learn from every patient. But the reality is that the level of scientific investigation that goes along with clinical studies is usually, quite limited, such that we can’t learn from every patient. We want to change that paradigm.

So, what I’m hoping is that within that one to five year span, we’ll actually change people’s views about what a clinical investigator looks like. And then we can learn from every patient.

PG: Is there anything we forgot? Anything we forgot to mention?

TJ: I direct the Koch Institute as you know, although I’ve announced the fact that I’m stepping down. That’s a separate story. We can talk about another time, perhaps.

But in any event, the Koch Institute was built on the thinking that collaboration, especially across disciplines, could accelerate progress. And I think it’s that same thinking that no one person, no one institution has all the right ideas, all the right technologies, all the right opportunities, honestly.

But through collaboration and especially across these powerful institutions, I actually think that we can do something here that’s been very hard to do in the past.