Last December, Flatiron Health convened a “hackathon,” an event where programmers, developers, and scientists pitch novel ideas and aggressively crunch data in a competitive sprint.

These events, also known as hackfests or codefests, are a staple of tech culture. No two hackathons are the same, and at that particular Flatiron event—the company’s 18th—35 teams were challenged to find the best uses for real world data in solving real world problems.

One team, led by health economist and pharmacoepidemiologist Blythe Adamson, proposed using Flatiron’s database to ask two big questions:

Does the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion program reduce disparities between black and white patients?

Are black patients with metastatic cancer getting timely treatment, compared to white patients, in states that implemented the expansion?

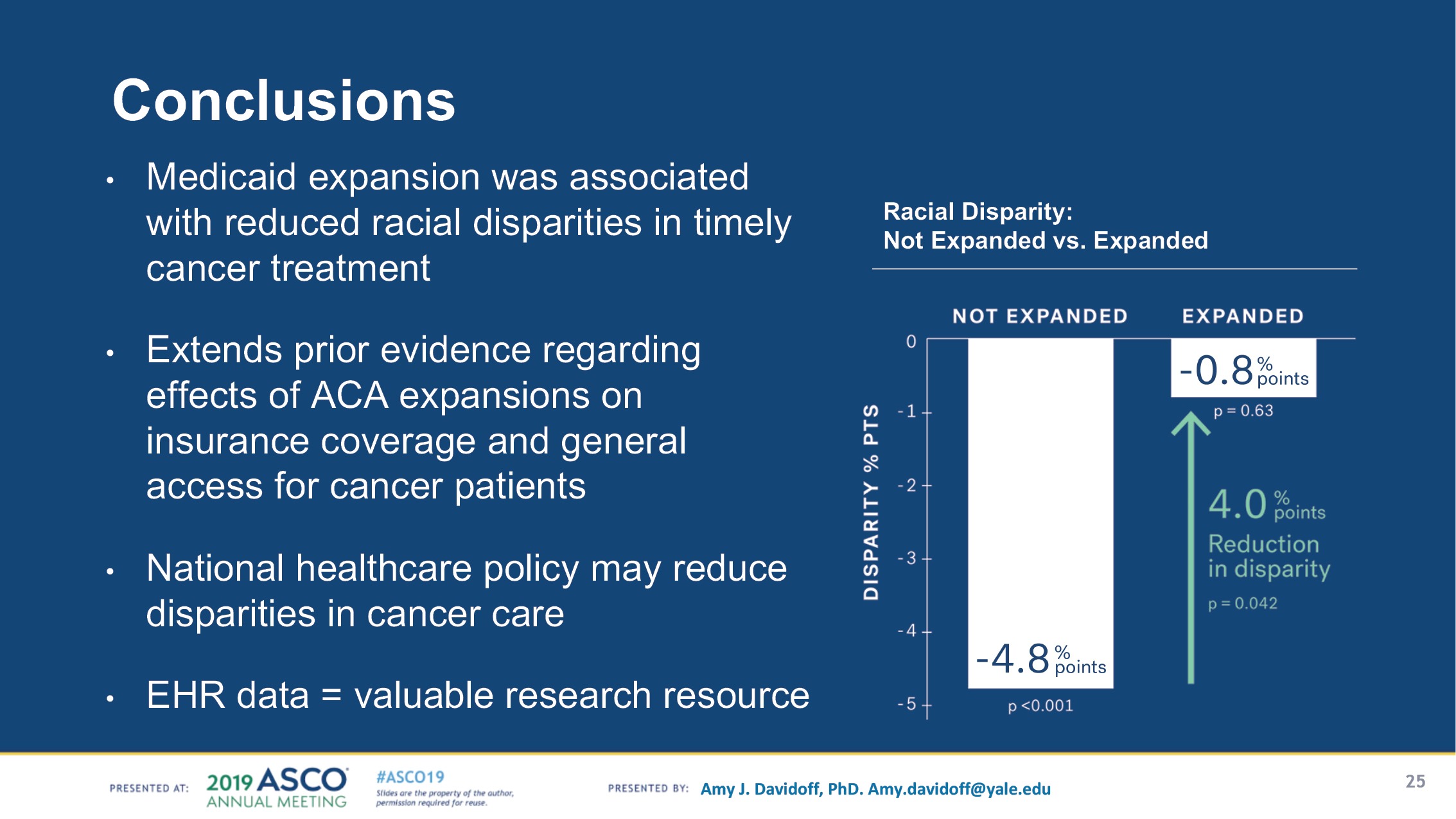

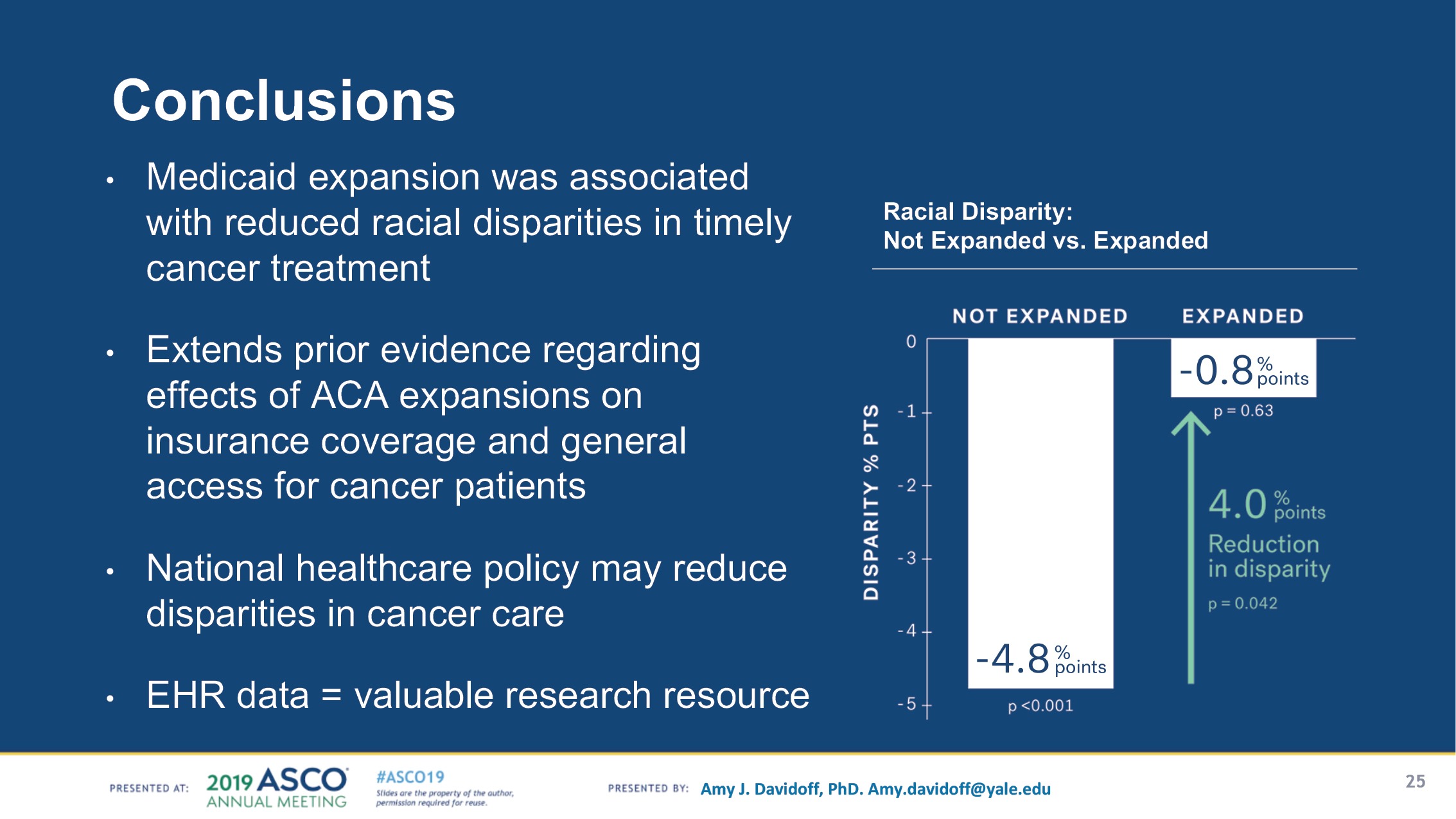

Adamson et al. dove into the company’s vat of data and emerged with the answers—Medicaid expansion is indeed associated with a significant reduction in racial disparities in states that implemented it.

Six months later, the team’s project would become the most-discussed plenary session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago. The study comes at a time of continued opposition to Obamacare by congressional Republicans. The broad health care reform initiative narrowly avoided a repeal in 2017, with three Senate Republicans defying their party’s efforts to end the ACA without an immediate replacement program.

After the results were presented at ASCO, Democrats on Capitol Hill promptly took to Twitter to highlight Adamson’s study.

“The Affordable Care Act helped reduce inequity within our country,” Senate Democrats wrote June 3 on their official Twitter account. “But the Trump admin and the GOP have continuously worked to undermine the law and take away health coverage from American families. Democrats will not stop fighting to #ProtectOurCare.”

The three-day hackathon began on Dec. 5, 2018, at Flatiron’s headquarters in Lower Manhattan. It was a Wednesday night, and a chilly breeze was blowing outside. Flatiron, taking note, had lined its communal picnic tables with trays of steaming hot dumplings.

One by one, employees announced their hackathon ideas. The next morning, everyone—statisticians, clinical data analysts, machine learning specialists, research oncologists—hunkered down, tapping away at their keyboards for two days, hoping to emerge victorious.

The grand prize? Bragging rights, and a stack of laptop stickers to commemorate the winner of the hackathon.

“They usually last one to three days, and you cancel all of your meetings, and form teams to work, or “hack,” on something you’re passionate about. And sometimes it can be pretty competitive,” said Adamson, a senior quantitative scientist at Flatiron. “Yes, you can motivate a bunch of nerds with something as silly as a laptop sticker.

“I got up on stage and pitched this idea—because I knew I couldn’t do it alone—saying that, ‘I think we should test this hypothesis. Did Medicaid expansion have an impact on racial disparities?’

“It’s pretty incredible to me that we could go from an idea that I had in the shower in November—to the ASCO Plenary stage six or seven months later.”

A conversation with Adamson appears here.

By Monday, Dec. 10, Adamson and her team had made history—their project was the first study to use real-world, real-time data to show that, in states that implemented Medicaid expansion, black cancer patients were getting timely treatment, nearly on par with white patients.

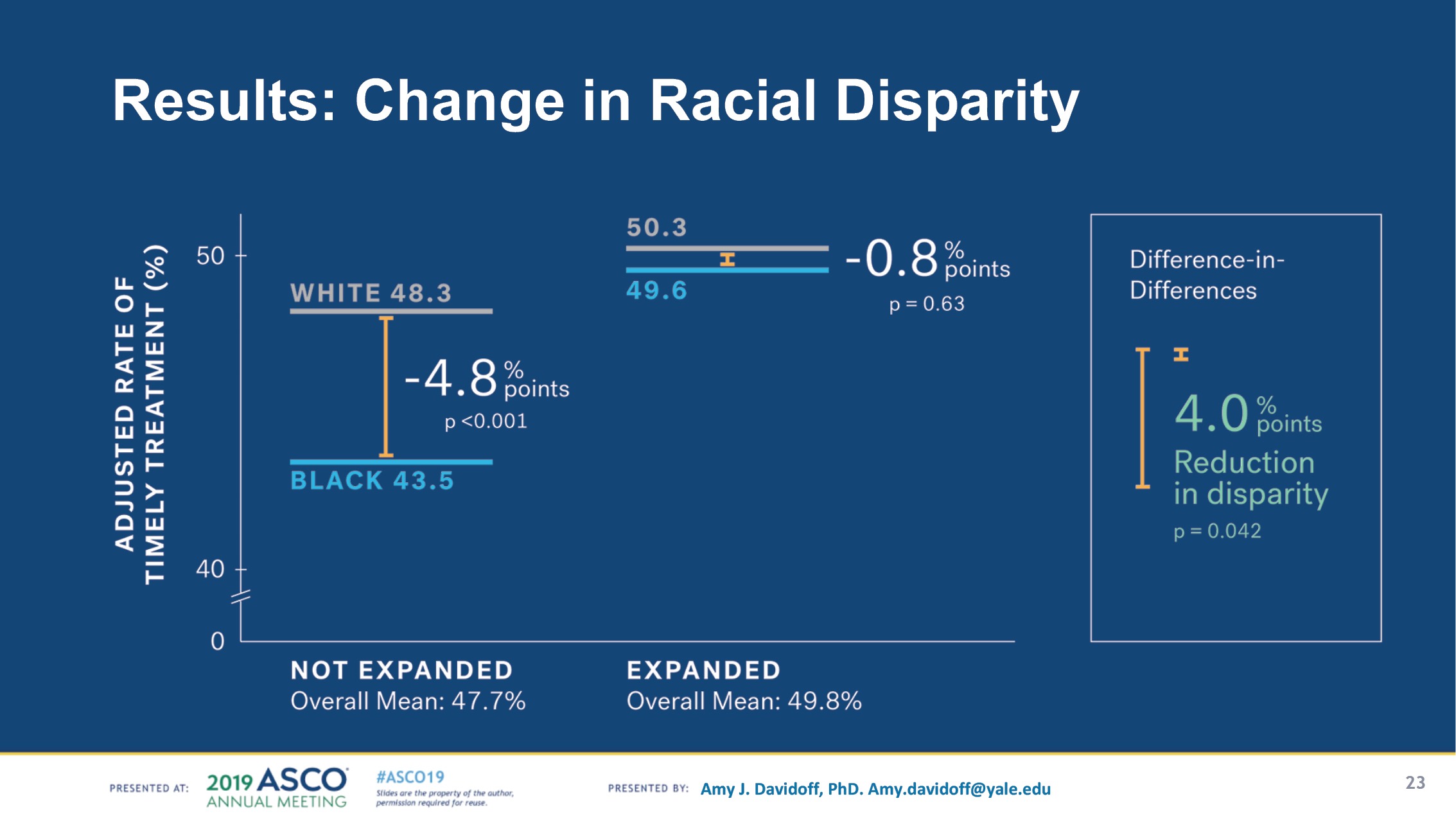

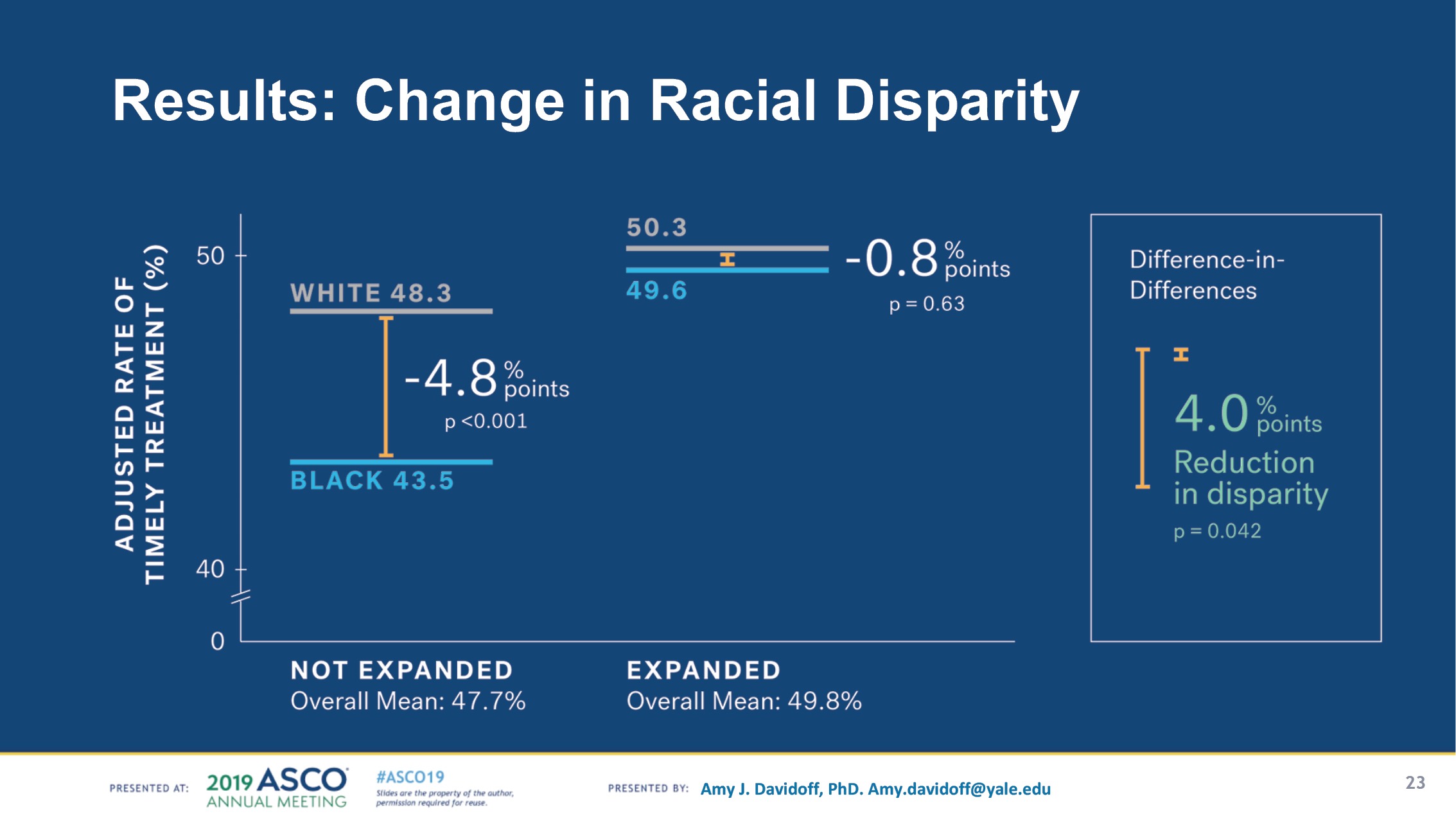

The results of the final analysis, presented at an ASCO plenary session, show that Medicaid expansion is associated with a 4% reduction in post-diagnosis time to treatment for black patients with metastatic cancer—effectively a near-elimination of racial disparities in timely treatment in states with Medicaid expansion.

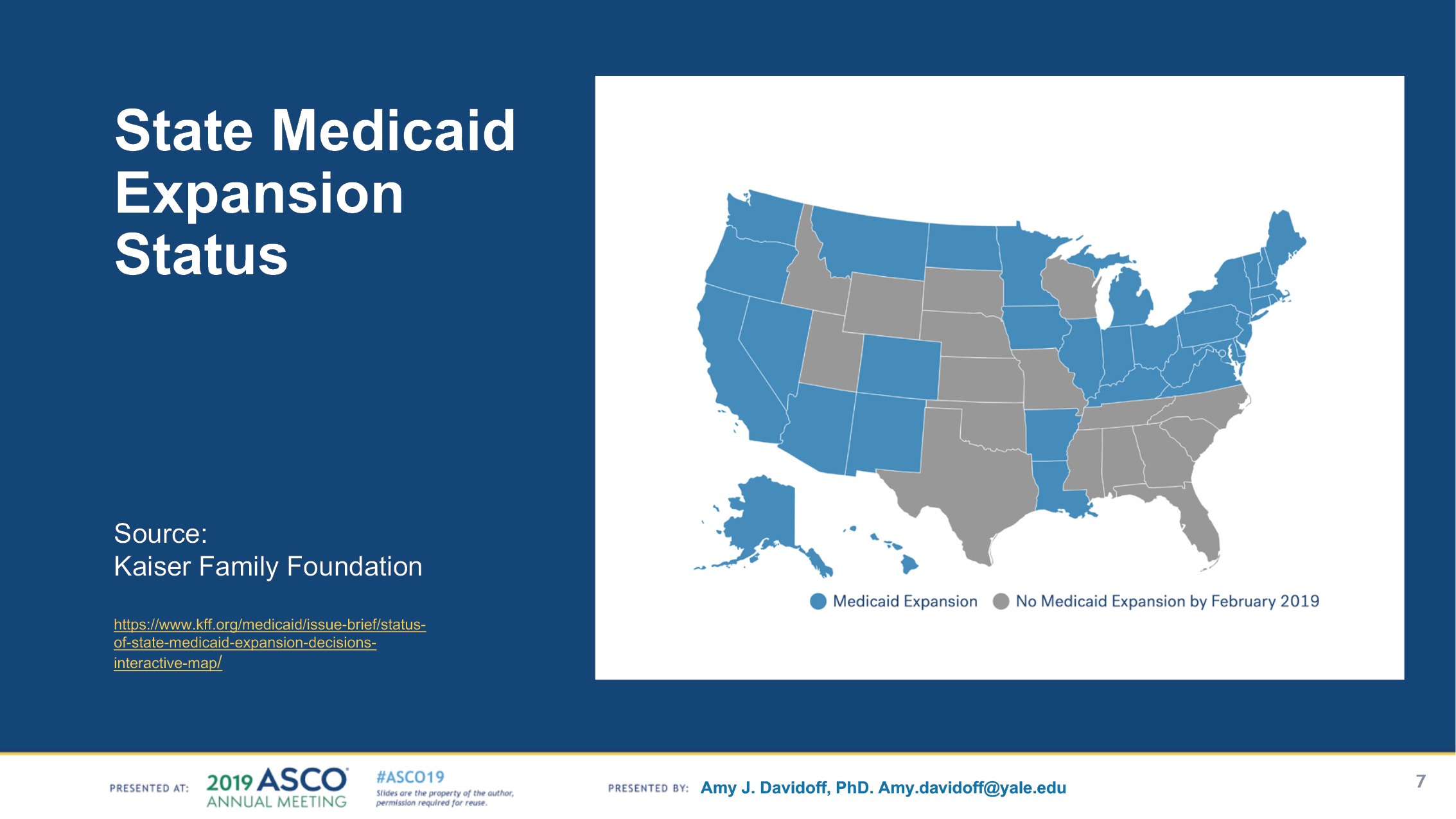

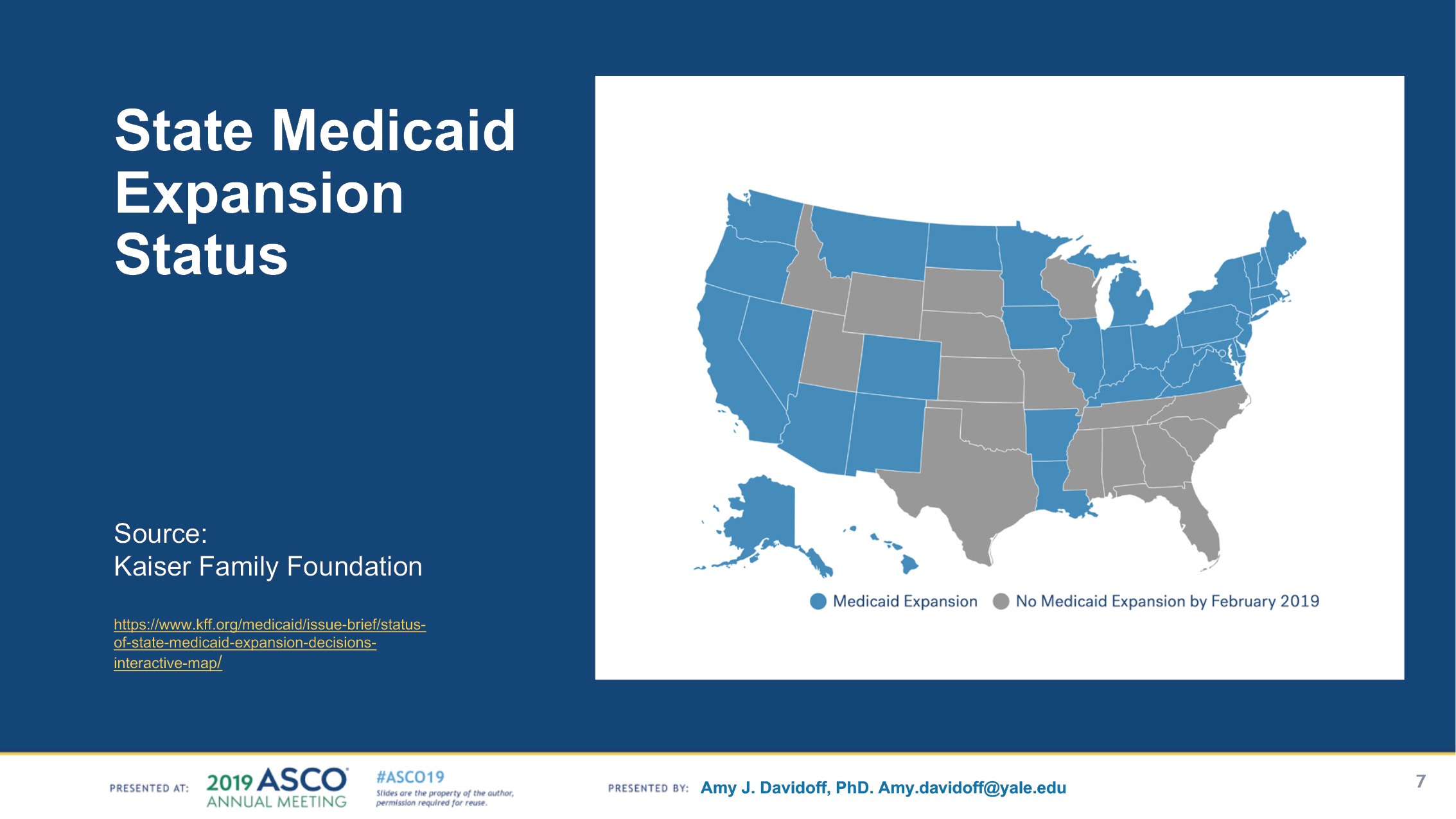

To date, 37 states, including the District of Columbia, have adopted the Medicaid expansion. Of that number, 34 have implemented the expansion. The patient data included in the Flatiron study are sourced from 27 of these states.

“Please note that we didn’t even win that hackathon—I believe we came in third place—but the response from people at Flatiron was so moving that we could tell, early on, that it was something that was really meaningful to people,” Adamson said to The Cancer Letter. “And when the call came around for ASCO abstracts, we sat back and had to make a decision: ‘Should we do this for real?’”

For the project, Flatiron teamed up with two researchers from Yale University:

Amy Davidoff, a health economist, health services researchers, and senior research scientist at the Yale School of Public Health, Department of Health Policy, and

Cary Gross, professor of medicine and epidemiology, and director of the National Clinician Scholars Program at Yale.

“Cary brought in Amy Davidoff from Yale, who is a famous health econ hero to me, already had published research showing that ACA and Medicaid expansion reduced the rate of uninsured cancer patients and shifted diagnoses earlier stages,” Adamson said. “And so, with Amy and Cary, we redesigned the methods to account for all the different potential sources of bias and get close to causal inference.”

I got up on stage and pitched this idea—because I knew I couldn’t do it alone—saying that, ‘I think we should test this hypothesis. Did Medicaid expansion have an impact on racial disparities?’

Blythe Adamson

This was Adamson’s first ASCO meeting. She had never submitted an abstract to the professional society before this study.

“In preparing for the ASCO abstract submission, we thoughtfully redid the study with care and rigor,” Adamson said. “It was well received.”

Rep. Adam Schiff (D-CA), chair of the House Intelligence Committee, and Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), ranking member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, too, chimed in.

“New research shows that fewer Americans, especially women and people of color, are dying of cancer because of expanded health coverage through the ACA,” Schiff wrote in a June 3 tweet. “Health care saves lives. That’s why we’re fighting so hard to make sure every American has access to quality care.”

“Thanks to the Affordable Care Act, the disparity in access to cancer care for white and African American patients has almost been eliminated,” Feinstein wrote in a June 3 tweet. “Further proof that the ACA is saving lives and improving care for millions of Americans.”

Andy Slavitt, a former acting administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services who led the turnaround of Healthcare.gov in the Obama administration, called Adamson’s study “Great news.”

“Since the ACA, African American disparity in advanced cancer diagnosis & treatment has almost entirely caught up to whites where Medicaid has expanded, a near 5% improvement,” Slavitt wrote in a June 2 tweet. “There is a right direction. Support those pushing for it.”

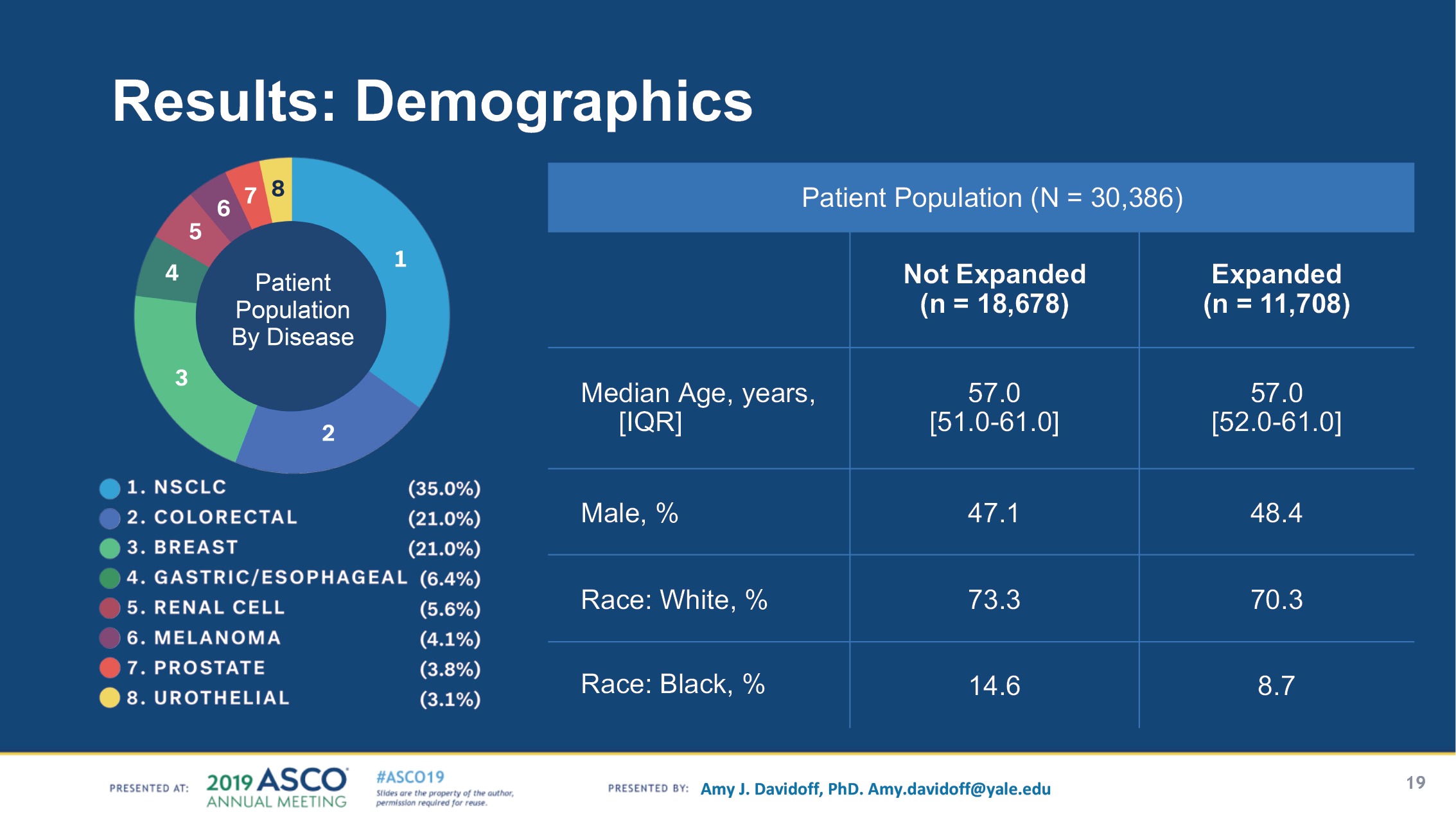

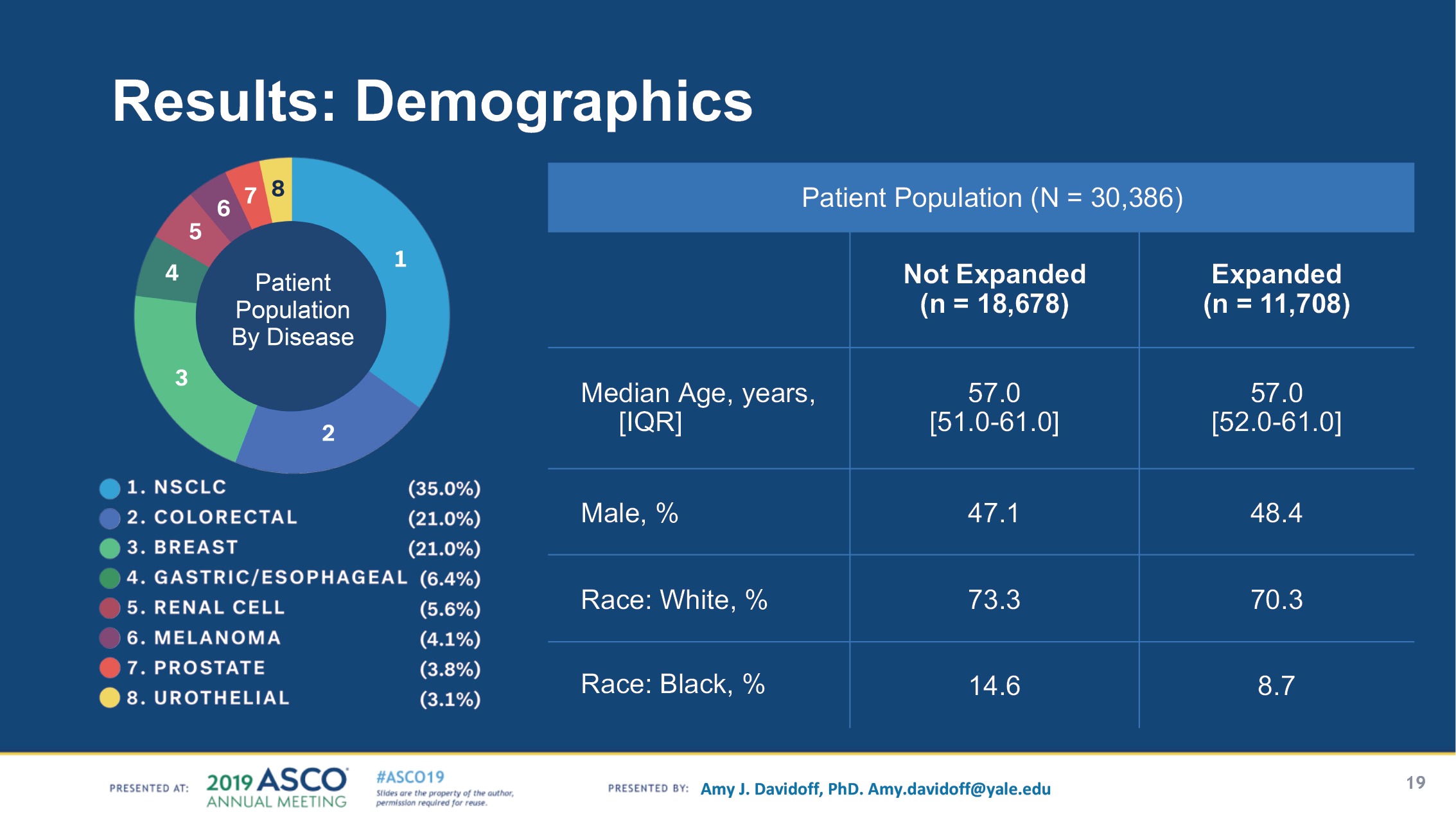

To study time to treatment, Adamson’s team divided Flatiron’s data on Medicaid patients into two cohorts—states with Medicaid expansion (n = 11,708), versus states without expansion (n = 18,678). The sample included patients with eight cancer types, with non-small cell lung, colorectal, and breast cancer making up 77% of cases.

Policies that improve access and decrease the time to treatment will serve to drive the value proposition in cancer care. Congress must understand that policies that improve access will not only improve patient outcomes, but drive down costs.

John H. Stewart

“In the case of evaluating health care policy, randomization is almost never possible. States would not allow themselves to be randomized to expansion or not expansion,” Adamson said. “We designed the next best thing one could do, using methods to mimic attributes of randomization.

“This is the first study that I’ve seen where we cut straight to the heart of what mattered to us, which was understanding if health equity improved. By pre-specifying our hypothesis and methods before running the experiment, it strengthened the scientific validity of the results. We certainly demonstrated the possibility to generate real time evidence for policy design.”

The results of the study, while correlative, builds on prior evidence regarding the effect of ACA expansions on insurance coverage and general access for cancer patients, said Syed Yousuf Zafar, associate professor of medicine and population health sciences at Duke University.

“An important point to make at the outset is, this is not a randomized controlled trial, and the results from the study are indeed correlation, showing association, not causation,” Zafar said to The Cancer Letter. “However, there have been experiments close to randomized studies that have actually shown similar benefits with Medicaid expansion. In that sense, I’m talking about the Oregon experiment.

“When Oregon expanded Medicaid access, they had to do so with a random lottery, just because of the number of people who applied for expanded Medicaid. And that random lottery basically served as a natural randomized study. In the results of that randomized study, they basically found that, in some cases, access to care, care utilization, and certain health outcomes improved with Medicaid expansion.”

The expansion of the ACA has several critical consequences that lead to the conclusions in the Flatiron study, said John H. Stewart, professor of surgery at the University of Illinois College of Medicine at Chicago, physician executive for oncology sciences at University of Illinois Health, and associate director for clinical sciences at the University of Illinois Cancer Center

“This study is extremely important as it demonstrates the importance of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in improving cancer care,” Stewart said to The Cancer Letter. “First, there is improved access to medical facilities. Second, many institutions have implemented navigation programs to facilitate the delivery of care for these patients across the care continuum and undoubtedly reduces the structural impediments to timely care that factor into racial disparities.

“Although this study is highly significant, it does raise several important questions. First, are there data that show a reduction in the time to treatment for patients with early-stage cancer? I believe that this will be the most important outcome of the PPACA. Second, are there data on differences in the utilization of palliative care? Finally, does Medicaid expansion reduce health care expenditures associated with the care of these patients?”

The results of this study are timely given the improvement in treatments for metastatic disease, Stewart said.

“Policies that improve access and decrease the time to treatment will serve to drive the value proposition in cancer care,” Stewart said. “Congress must understand that policies that improve access will not only improve patient outcomes, but drive down costs.”

The Flatiron study is proof of principle that real world evidence can be used to examine and inform health policy interventions, said Zafar, who led a discussion of Adamson’s study at the ASCO plenary session.

“From a data standpoint, we need better use of real world evidence to help inform population-based outcomes,” Zafar said. “Importantly, I don’t think real world evidence can, today, replace our gold standard for efficacy, which is randomized controlled trials, but it can inform quality of cancer care and population-based outcomes, very much like this study did.

“They did a really nice job. I believe there has been one other study that has looked at time to treatment with Medicaid expansion. If I remember correctly, that study was done just in Kentucky. The Flatiron study was done in the metastatic setting; that study that was done in just one state was done in the adjuvant setting in early-stage cancer. And that study actually did not see any improvement in time to initiation of chemotherapy with Medicaid expansion.”

The impact of Medicaid expansion in North Carolina on cancer patients would be immediate, Zafar said.

“I happen to live in a state that has not expanded Medicaid access,” Zafar said. “So, during my plenary discussion, I talked about my patient, Sylvia, who has metastatic pancreatic cancer, applied for Medicaid when she lost her insurance soon after her diagnosis, and unfortunately was told she was not eligible for Medicaid in North Carolina, because her income was too high.”

“Now, interestingly, her income was $18,000 a year. And despite that very low income, she’s still not eligible for Medicaid. So, I could see the immediate impact Medicaid expansion—in a state like North Carolina—would have on my patients, and how they can afford and access health care.”

Under the ACA, Medicaid eligibility is extended to nearly all low-income individuals with incomes at or below 138 percent of poverty—$17,236 for an individual in 2019, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

This expansion fills in historical gaps in Medicaid eligibility for adults and was envisioned as the vehicle for extending insurance coverage to low-income individuals, with premium tax credits for the ACA Marketplace coverage serving as the vehicle for covering people with moderate incomes. While the Medicaid expansion was intended to be national, a June 2012 Supreme Court ruling essentially made it optional for states.

“I think this study presents really timely evidence that health policy interventions are needed to improve access to care for our patients,” Zafar said. “In terms of moving forward, I would advocate for Medicaid expansion at the state level, obviously, and that would be an important policy step.”

Back at Flatiron, Adamson has already started working on her next big hackathon project—using real world data to elucidate the safety and efficacy of cancer immunotherapies in people living with HIV.

“There’s absolutely no evidence about the safety or efficacy of these drugs in people living with HIV, which to me is crazy, because with HIV, you’re more likely to develop cancer—and then, to have no understanding about whether there’s an interaction between the drug efficacy and the virus,” Adamson said.

“So, at the Flatiron Hackathon 19 in March, we identified patients with HIV who had used immunotherapy and matched them to patients just like them—diagnosed in the same year with the same stage and disease and type of drug, similar in every way except they don’t have HIV. We compared overall survival outcomes for immunotherapy in people with vs without HIV.

“Would anyone ever be incentivized to pay for and run a large randomized trial of this? I doubt it. I designed this to be a companion study to CITN-12, a phase I study looking at safety of pembrolizumab in cancer patients living with HIV.

“So, to have a prospective trial looking closely at safety alongside a retrospective study of effectiveness in the real world, it can give us a whole new and more complete picture of risks and benefits for a marginalized population that matters.”