The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that real-world data is an indispensable tool healthcare professionals should use to rapidly respond to emerging gaps in care delivery.

The “deep-dive” panel, which focused on the intersection of big data, pandemics, cancer, and public health, was coordinated by this reporter and hosted by the Association of Health Care Journalists April 30. The speakers included:

- Robert A. Winn, MD

Director and Lipman

Chair in Oncology, VCU Massey Cancer Center;

Senior associate dean, cancer innovation, Professor, pulmonary disease and critical care medicine, VCU School of Medicine - Rebecca A. Miksad, MD, MPH

Senior medical director, Head of strategic affairs, Flatiron Health;

Associate professor, hematology and oncology, Boston University School of Medicine - Dana E. Rollison, PhD

Vice president, chief data officer, Associate center director, data science, Moffitt Cancer Center

The COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to inspiring many a layperson to become an armchair epidemiologist, has created the need to use real-time, real-world data for deciphering trends and identifying unmet needs. It’s important that health systems invest and develop these capabilities for informatics and data analysis, the speakers said.

“COVID has really, I think in a good way, shone the national spotlight on the importance of data,” Moffitt’s Rollison said at the panel session, which took place in Austin at the AHCJ 2022 Health Journalism annual conference. “If we really want to understand what’s happening in our communities, in groups of patients and individuals that may not fit into that framework of a clinical trial, we need to leverage real-world data.

“Some of those data capture systems are inspired by cancer research, but now can be leveraged for COVID. And how do we use these large-scale data systems to understand what’s happening for the whole population? But importantly, have those breadth of data collection systems to dive into small communities that may be impacted differently.”

As inequities worsened during the pandemic, the need for robust real-world patient data became increasingly apparent.

These data were crucial to informing interventions at all levels in health care—amid delays in clinical care, inequalities in vaccine access and uptake, and stark differences in mortality rates.

“Whether that’s racial, ethnic minority groups, whether its geographical regions, whether it’s people with particular conditions who may be most vulnerable, this is where big data can really be leveraged to enhance our understanding not just of cancer, not just of COVID, but also how all of these health issues are interrelated and are important public health priorities,” Rollison said.

As we think about artificial intelligence, and the power of computers to leverage big data, and make advances on our understanding, those are incredible tools that I’m excited to embrace in the research area. But we have to understand that those are tools that can basically magnify the biases in the underlying data themselves.

Dana Rollison

Clinicians, regulators, and policymakers should apply lessons learned during COVID to solve problems across the healthcare system, VCU’s Winn said.

“Primarily, since the ‘70s, our outcomes data has been mostly biology,” Winn said. “I think in the era now, as we’re moving through COVID, it’s clear that we have to focus on the impact of the ZNA on the DNA and the biological outcomes. And that ZNA is the ZIP code association.

“So, as we’re starting to think about big data, small data, how to integrate all these data, it really is an amazing, I think, inflection point about how do we put all the pieces together.”

The pandemic created many natural experiments that the healthcare ecosystem can learn from, especially in oncology, said Flatiron’s Miksad.

“There are so many things that we haven’t yet really uncovered in terms of how COVID and the disruption of the care system really impacted our patients,” Miksad said. “For example, all my patients that I could put onto oral chemotherapy, I switched them off intravenous therapy as quickly as I could. So, maybe actually I don’t need to have all my patients on intravenous therapy. Maybe they would be completely fine always on oral therapy.

“Those are the types of questions that we might have considered before, but no one would ever have done a study about it. And here, we are having a natural experiment where we can see what happened to all my patients—that I switched from one chemotherapy that was considered the best to what was considered the second best—because of the COVID pandemic.”

When interpreting health data and translating insights into policy, physicians and journalists alike must consider the role that sociopolitical structures play in determining patient response, engagement, access, and trust, Winn said.

“There have been, for decades now, stories, mostly from the science side, but certainly from the press, about how African Americans—I’m picking on African Americans just for a second—are resistant to clinical trials,” he said. “The most recent literature—actually should guess that that was bunk all along—that what was happening was that people weren’t asking.

“You can imagine at a middle school dance, if you don’t get asked to dance, then they’ll say, ‘Oh, she never dances with anyone.’ Well, no one ever asked.

“For decades, I think both press and science have been talking at, over, but not to the very same communities that we’re depending on them understanding and being connected to and with,” Winn said. “Many of us who are reporting and writing about this have to be a little bit more conscious that bottom line is they don’t trust us. But when I go in my hoods—vernacular for neighborhoods—they also don’t trust y’all either.”

As real-world data continue to become a central component of strategic plans at hospitals and public health organizations, oncologists and other healthcare workers need to be aware of the pitfalls in data innovation.

“There are other aspects of data collection systems, systems that collect information from hospitals,” Rollison said. “Well, what about the communities that aren’t going to those hospitals? Those data aren’t making it into those national data collection systems.

“And as we think about artificial intelligence, and the power of computers to leverage big data, and make advances on our understanding, those are incredible tools that I’m excited to embrace in the research area. But we have to understand that those are tools that can basically magnify the biases in the underlying data themselves.”

Proving statistical significance may be a cornerstone of high-level evidence—i.e. in the drug development and approval lifecycle writ large—but the test is not a requirement for speedy hyperlocal interventions based on real-world data that can have an immediate impact on patient outcomes and quality of life.

“When you come down to the local center, we’re not looking for statistical significance in understanding patterns in patient care locally, we want to see what are the differences we observed, and act on them to try to mitigate those disparities. And why?” Rollison said. “Well, because deploying interventions to, for example, improve the [patient-reported] questionnaire uptake in groups that are not taking the questionnaire, or to go out into the community and offer screening services to those communities we observe have lower rates. There’s no downside to that.”

Physician-scientists, regardless of specialty, should focus on academic relevance, and on partnering with patient communities to ensure that biomedical research and public health interventions are being tailored to what the communities need, the speakers said.

“I love Dr. Winn’s patient-to-pipette analogy. And what gets us from patient to pipette is real-world data,” Miksad said. “We have the stories, which are really important, the N-of-1 stories. And then we have national-level, real-world data.

“We also have hospital-level data, that helps us really bring what the patient experience is, and what they need from us scientists, so that the scientists then can work on it. And then, it goes back the other way, such as the discussion around vaccine uptake.

“Real-world data can not only show us what happened; more importantly, it can show us what went right, when we could do something.”

Excerpts of presentations by Winn, Miksad, and Rollison follow:

Robert Winn: When COVID first hit, everybody in the United States and the world was concerned. The most interesting part about this is that it quickly became clear that what COVID shone a light on issues around disparities.

So, during the COVID period we actually now all become #SocialDeterminantsOfHealth. We now talk a great deal about the issues around the upstream determinants of health, how housing and employment play a role, as if this was new.

As people were socially tagging the social determinants of health hashtag, I’m reminded that those social determinants of health came from structures.

One of the things that I really hear about this epidemic world, as we got through the pandemic, is this continual drumbeat, as if those people in these neighborhoods didn’t want to get access, those people in these neighborhoods must have something genetically, as opposed to understanding that those people that we talked about actually did not have access to the full menu of the opportunities.

They had a very reduced menu. And all of a sudden, we’re creating this context, this drumbeat from communications and even from journalists— this constant drumbeat of what’s wrong with them.

We also understand that those communities that were redlined are actually the same communities that have businesses and commerce that actually were negatively impacting those communities. And, yet, we still talk about their DNA as opposed to their ZNA.

We talk about how they’re predisposed to COVID and how they are just simply more predisposed to cancer, without understanding the Z-nome that surrounds them. That is the ZIP code neighborhood association and the interplay it has and the impact it had, not only on cancer, but on this COVID issue.

COVID forced me to think about things differently. One of those things particularly about, again, that there was a loss of a year for most Americans. But there were almost close to three years for African Americans, and yet, again, the refrain when I saw this in the news was what was wrong with those communities and what’s wrong with the biology of those people.

And at no one point was there a consideration of the structure. We talked in hashtags, social determinants of color, as if it was just something to be bantered about, as opposed to understanding the structures that created those social determinants of health I mentioned.

So, it should come as no surprise that as we moved through the COVID process, we actually had the discovery of the new vaccine and everyone was super excited. But I was not. I was not because history has taught us that with every scientific progress, it unintentionally creates disparities.

Although my colleagues were all excited about it, I said listen, “This is actually going to be an unfortunate thing that we’re going to have to, right from the beginning, understand that we did not actually roll this out with all communities having equal access from the beginning.”

We talked about the miracle of the mRNA vaccine. We patted ourselves and gave ourselves, even self high-fives, about how brilliant and how bright we are.

And, yet, when it rolled out in that first year, you had this disparity that stood us right in the face. And many of you wrote about this. This is why I took this stuff, this was from the CDC and from your news reports, backed up by the CDC.

With every new scientific progress comes an unintentional but interesting inequity that we actually can prove, that we introduced, including the writing about this. And this is where I want to get at, because I think that there’s a lot to be done with structure, data, communication.

We’ve actually had the press, social media, the written media talking about the vaccination rates for Black Americans and white Americans not being the same. That was to be predicted.

But why am I so optimistic standing here before you, in front of you?

We talk about how they’re predisposed to COVID and how they are just simply more predisposed to cancer, without understanding the Z-nome that surrounds them.

Robert Winn

I’m going to tell you why I have this optimism for this COVID period. I think it’s going to be translated into our next biggest thing that we’re going to have to deal with, which is all the people that did not get screened for cancer, and the lessons learned from COVID.

We need not only just a better vaccine. We need better vaccine access, not better vaccine attitudes. So let me just tell you what we just did as a society, as a people, and why I’m super excited that if we pay attention and humble ourselves to what we really just all witnessed, we’ll be able to even probably have a better impact in the context of reducing the spread of getting cancer. What do I mean?

In Virginia at the time, when I was doing this, we had almost in some neighborhoods a four-to-one disparity in the uptake of vaccines. What did I learn? And what did we learn?

We learned that having the science alone and a good vaccine was necessary to take on the issues around COVID, but not sufficient. At the very same moment we have all these miracle drugs associated with COVID, we also have the most robust miracle drugs associated with cancer.

What did I do? The very first thing we did was something we called Facts and Faith Fridays. My partners, Todd Gray from the Fifth Street Baptist Church and Rudene Mercer Haynes, got together. Remember, Richmond is roughly 50% to 60% African American. So, we really had to figure out how to do that, and a lot was rural.

Every Friday, from April 2020, a committee that the cancer center directed and my team would show up initially by a phone call and then we got our high tech in and we went to the Zoom. We initially started with phones, because what we found out is that many of our rural areas didn’t know how to hotspot, so they were disadvantaged—Brunswick, people in Lynchburg and Danville and these other areas—they couldn’t actually get on the Zoom.

The issue of the digital divide, which I’ll come back to at some other topic, actually was something that was occasionally talked about, but not really have we circled back and figured out well how was that addressed.

Let’s just talk about this simple act of getting this group together of faith-based communities that range from on most days, 75, but on other days 500. People that were respected in the neighborhood. It would have been easy to send out healthcare workers, but nobody believed them in our neighborhoods, least not in Richmond. It was a low-trust environment.

We recognized that by having people from those neighborhoods and partnering with those people and giving them the best and most successful data, they were able to do things that as a health professional, as a data person and as a scientist, I was not able to do at the time.

On this one call, we decided to get some of the best top people, because these people, faith-based leaders in the community said, “Let me hear from Fauci directly.” So, we did things like that. We got Fauci. We got the first lady. We got other people.

In fact, as a result of the people being able to talk to these folk directly, the community was much more motivated to mobilize, to open up not only their churches but other community centers, to work with the Virginia Department of Health. There was power in the community that is frequently missed when we only write about the miracle of the mRNA vaccine.

This is national data. It’s not from me. You can find it anywhere else in the United States. But the uptake of the received at least one dose of the vaccine that was a four-to-one difference—and in some cases a three and in some cases five-to-one depending on the community—has been all but erased.

In fact, I just looked at my data today from Virginia this week. When I think about the African Americans versus white sort of gap, it’s been closed.

By the way, when I looked at my 12- to 35-year-olds, the uptake in the state is roughly 75+%. When I look at my 35 to 65-year-olds, it’s in the >80%. And certainly the 65-year-olds, it’s 90%.

Now, what does that account for? Does it just account for the fact that, as a state, when I talk to the governor, when I talk to Virginia Department of Health commissioner, that it was just, we had the drug?

It was not. We’ve gone to sleep on writing about those amazing communities that can pull together and that had not only high-tech on the mind, but high-touch in action of how we close this gap.

So, in that, at the end of the day—and Matt and others have written about this, about the disparity gap—that’s about the thing that’s about to come crashing as a wave, which is cancer. And we understand that screening is going to be key to that.

This article that was in The Washington Post about COVID and cancer, a dangerous combination, especially for people of color, is absolutely true.

But here’s why I stand before you with some optimism. If we can close the gap in COVID, we can learn the lessons from not what we did but how we did it. What were the approaches? What were the necessary resources and what were the different tasks that the many communities take to, and actually repackage it in a way so we can actually do what is going to be necessary to do for the war on cancer in this community?

I am so passionate about the science and so passionate about the concept of people informing our pipettes, and that the power comes from data from our community and how we use the data, but more importantly, how we integrate our communities as partners as we try to reduce the disparities gap, not only in COVID, but in cancer.

Rebecca Miksad: Let’s dig a little bit into oncology and why oncology is at the forefront of real-world data.

So, we have genetic profiling. We have rare study populations, combination chemotherapies, accelerated approvals—most common in oncology—cancer immunotherapies and various antibody therapies, value-based care.

And also, for the first time, I’m adding COVID to this slide, because it really was different for the cancer population. And those natural experiments I opened with really do help us understand the lessons learned for the rest of healthcare.

So, a few moments about Flatiron itself. Flatiron was founded in 2012 by two tech leaders on a mission to apply tech to challenges of cancer, specifically unlocking the stories and lessons learned from patients themselves. And we’ve spent the last decade making this a reality. Our earliest research was with the FDA and with the NCI, so, very much always focused on the scientific aspects.

The COVID-19 pandemic was an unprecedented shock to the modern healthcare system, regardless of diagnosis. But care for cancer patients is particularly sensitive to care disruptions because there’s really very little leeway to how and when cancer care is delivered.

Cancer care is regimented in order to minimize the toxicity of the therapies we give and to optimize outcomes. And any time they can’t follow those regimens, we get nervous because we worry about suboptimal outcomes for our patients.

An electronic-health-record-derived real-world data, relative to the other types of observational data, like claims or cancer registries, has the potential to more accurately capture these changes and to do it in real time.

As a clinician, I sit here and I write my notes within the electronic health records system that is immediately available, the same day, to anybody who has—of course, HIPAA de-identified—access in order to be able to understand how patients are doing in real time.

Real-world data really does provide that rapid turnaround to identify unexpected pitfalls and unintended consequences of systemic changes in healthcare delivery and any other progress that we’ve made in healthcare.

Rebecca Miksad

And because of that sensitivity of cancer care to disruptions, oncologists serve as a guide for the value and roles of real-world data and real-world evidence throughout healthcare.

So, let’s see what real-world data can show us.

At the beginning of the pandemic, I saw patients once a week with colon cancer at Boston Medical Center, one of the hospitals hardest hit by the pandemic. I never missed a day of clinic.

However, I kept as many patients home as I could possibly do so, including as I mentioned before switching patients from intravenous chemotherapy they had to get at the clinic to a pill that they could take at home. My in-person visits dropped.

But was that really just my experience in Boston at an academic medical center that was a safety net hospital? Or was that also happening in the community clinics in other areas of the country where the COVID pandemic hadn’t really hit yet?

So, we asked that question with our data from Flatiron, which covers about 80% community patients and about 20% of our data is academics.

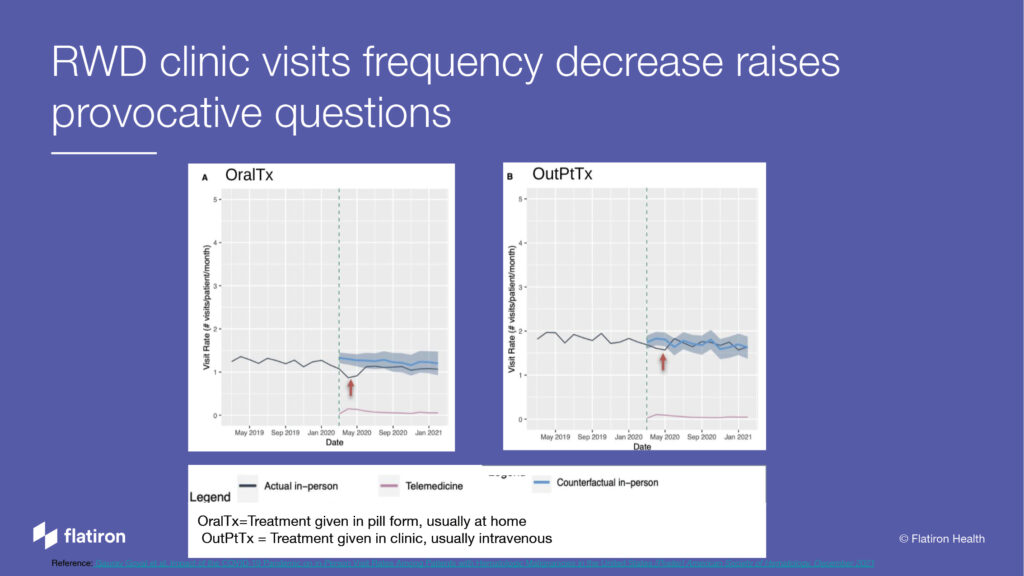

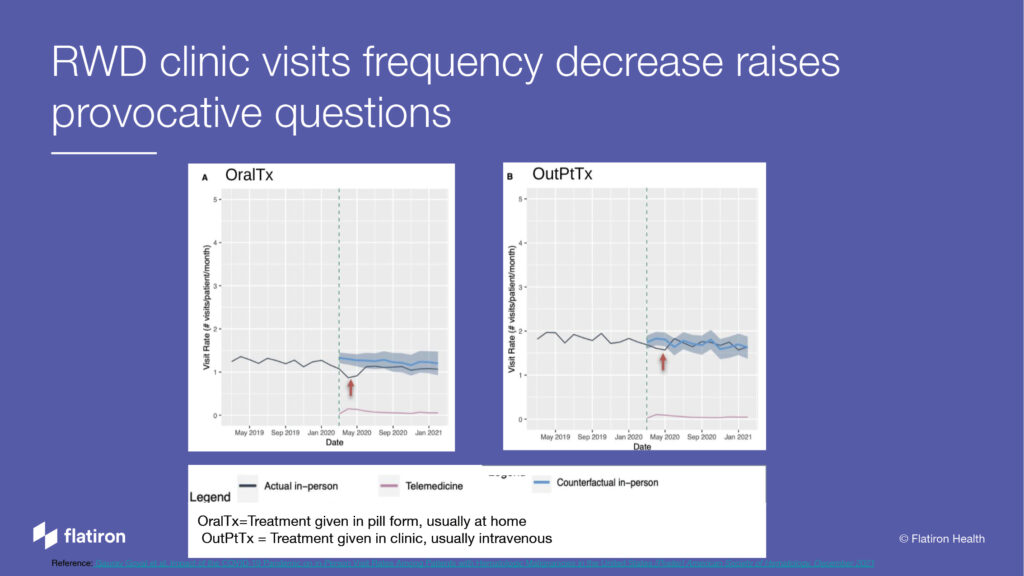

This is a study about hematologic patients, so cancer patients, people with ALL leukemias, chronic leukemias, multiple myeloma, those types of diseases. And we saw here: the bottom line is time, that dotted green line is when the pandemic started officially, and you can see the black line there is the number of visits.

And once that green line hit down, it dropped in terms of number of clinic visits for these types of cancer patients.

So, maybe it was supposed to be happening anyway, that curve was coming down a little bit before. But actually, on using research methods on the real-world data, what should have been happening is that blue line with that gray area around it.

So, you can see that there was a significant drop in clinic visits, and it never really recovered, because it never went back up to that blue line.

That first graph is for oral treatments. The second graph is for IV chemotherapy treatments. And look, there’s a difference there. There was an initial dip also post-pandemic, after the pandemic started.

And then, the inpatient, clinic visits for chemotherapy actually went back to normal. That’s super interesting. How can we get away with fewer clinic visits than expected for oral treatments and not intravenous treatments? And this is on a dataset of 22,000 patients.

Real-world data also looked at in terms of advanced solid cancers, like lung cancer, breast cancer, colon cancer, to find some hidden truths about the reality of the COVID-19 pandemic.

So, this is a study looking at 14,000 patients who had new diagnosis of advanced cancer. So, patients who got diagnosed during the pandemic. And we wanted to say, how are these patients doing? Are they actually getting appropriate cancer care?

We were really worried that people were getting delayed in terms of getting chemotherapy, which would decrease their outcomes. And that was our hypothesis going into the study.

We were wrong.

This study actually demonstrates that the time to treatment was the same pre- and post-pandemic. This group of researchers was led by Penn and about 10 other institutions, and we sat in the conference room saying, “Okay… Wait… Why?”

And this was in real time. And this hypothesis we had about some disaster happening was wrong.

So, now, we can come up with some hypotheses. Because there was fewer clinic visits—remember the slide before—that actually meant that there was more chemotherapy chairs available, more doctor appointments available for those patients who were newly diagnosed and needed treatment right away.

I was like, “Of course. That’s what happened in my clinic.” It was totally empty, because I kept everybody home. So, anybody who really needed treatment actually had a pretty easy time getting it.

There’s also a decreased surveillance of people who had cancer and then were followed by CAT scans. And so, we weren’t picking up those new diagnoses as frequently. Actually, there was a decrease in the total number of patients with new diagnoses of cancer.

So, that also freed up some chemo chairs. And the same thing for screening, decreased screening, meant there were fewer diagnoses, particularly for advanced cancer care.

There were all sorts of other things that happened. We stopped doing surgery upfront. We started getting people into chemotherapy first. We had more streamlined workups.

All of those are super-interesting natural experiment questions that we’re really excited for you guys to unmask and really help us understand what we can learn about our healthcare system and what happened, and what other assumptions and hypotheses we can turn on their heads.

Again, I’ll also take a moment to talk about telemedicine. And I really like the way Dr. Winn phrased it in terms of, every time we have an advancement, we often inadvertently make health inequities worse for a variety of reasons. And this also happened with telemedicine.

So, this, again, is hematological malignancies, leukemias and myeloma patients. Over time, the telemedicine visit rates for white patients and Black patients—the Black patients had much fewer telemedicine visits. In some ways, maybe that’s good because they’re getting in-patient visits.

But I actually would posit, like Dr. Winn said, maybe they just didn’t have the access to the internet or didn’t have the ability to have those telemedicine visits. And what harm actually came from having to go in person? What harm is averted for some groups of people and not averted for those Black patients who weren’t able to have telemedicine visits?

That gets to the structures that Dr. Winn spoke about in terms of health inequities and how real-world data can help us peel back some of those layers to understand what was happening.

If we really want to understand what’s happening in our communities, in groups of patients and individuals that may not fit into that framework of a clinical trial, we need to leverage real-world data.

Dana Rollison

So, what are some of those structures in addition to access to high-speed internet? Well, billing. Our insurance carriers took a little bit of time to figure out the coding so we could bill for telemedicine. And those really had on-the-ground impact for us who were caring for patients and the patients themselves.

Lessons learned in real-world data from oncology do impact the healthcare system at large.

Real-world data really does provide that rapid turnaround to identify unexpected pitfalls and unintended consequences of systemic changes in healthcare delivery and any other progress that we’ve made in healthcare.

Real-world data facilitates hypothesis generation about treatment effectiveness and outcomes. You’ll hear from the next speaker about how you can dive deep using real-world data to test and understand these hypotheses better.

With any tool, you do need to understand how to use real-world data and its limitations.

I’m going to take a small detour here and talk about clinical trials. I was a clinical trialist. And clinical trials are the gold standard, they’re never going away, and I want them to stay.

But there are so many questions that are not going to get answered if you wait around for clinical trials.

Dana Rollison: Matt asked us to talk about how has the cancer community helped to inform what they know about COVID and how we’re gaining more and more information about COVID.

I have three vignettes focused on information and research systems that were in place for cancer research and were able to quickly pivot or be expanded to increase our understanding of COVID as the pandemic was emerging.

The first is focused on cancer registries. So, many of you may be familiar with what a cancer registry is. At a population level, it gives us information on cancer incidence rates, survival rates so that we can understand what the patterns are over time by geography and different populations.

Cancer registries, at their heart, are coming from the hospitals and the physicians that are seeing these patients and entering the data that are then aggregated at the state and the national levels.

And it takes, actually, years before you get data at the national level from a cancer registry.

But being in a hospital setting, you can look at your own data very quickly, and that’s what we’ve begun to do at Moffitt Cancer Center, where we have about 20 people in our cancer registry that go through electronic medical records for over 15,000 new patients who are receiving a diagnosis and/or cancer treatment at Moffitt Cancer Center.

They’re extracting information on diagnosis and treatment—much of the data that you’ve heard is in the Flatiron database.

So, what we’re doing with this is taking an early snapshot and trying to understand the impact of the COVID epidemic on cancer diagnosis and treatment, which is the first intersection between these two diseases.

As you’ve already heard, COVID impacted our healthcare delivery system.

And the impact on cancer is likely twofold: people delayed screening as well as the impact on the treatment itself. And how are we going to measure COVID’s impact on the delayed screening? It’s likely going to be a shift in the distribution of stated diagnosis; right?

Meaning, if people didn’t get screened and now, they’re coming back after the pandemic, the cancers that are being found may be in a more advanced stage, because they delayed their screening.

This can be measured in the population level, using the cancer registry data. We won’t see national data for another probably year or so, because it takes that long to aggregate it across all hospitals, make sure that the data are high quality and then release it to the public.

So, this is an early view at the hospital level. And in these bars, you can see that in later years, COVID and beyond, 2020, 2021, so those two bars to the right, we saw a shift. So, you see in-situ and localized, those are the early stage.

Regional and distant on the right are the more advanced stage.

And in the later years, the proportion of cases that were detected at a localized stage and this is colorectal cancer, decreased while the regional cases increased.

So, what that tells us is that, perhaps, if people delayed their colonoscopies or other colorectal cancer screenings during the pandemic and they came back after COVID, we’re seeing that a larger proportion of those cases are now regional versus localized and, perhaps, that is an impact of delayed screening. This is how we can use registry data to understand these patterns.

Now, another way in which we use registry data is similar to what you’ve heard in the previous talk around, what are the actual changes in how the cancer was treated because of COVID? And it could be a variety of reasons, which you’ll see in the next slide.

But, here, we’re using our cancer registry to say what percentage of our patients at Moffitt Cancer Center actually had an impact, a COVID-related impact on how we treated them. And we looked at this by cancer type.

So, overall, it’s about 3.5% of our cancer patients whose treatment was fundamentally changed because of COVID. And that varies by cancer type. You can see breast and cervical cancer are the most common cancers in which COVID impacted that treatment. And those are screening-detected cancers.

We wanted to look at the reasons for the treatment delay. Delay is the highest most common reason or effect, if you will, of COVID on the treatment itself.

In many cases—you can see breast, cervical toward the top, and colorectal and prostate next—most of these impacts from COVID were from a delay of treatment.

So, that could mean either patients took longer to come to Moffitt, or once they were at Moffitt, it was harder to get them scheduled for surgery or for their radiation treatments because of COVID.

There are other cases where the treatment was altered. So, you’ve also heard about ways in which physicians may have made these decisions differently because of the pandemic.

Maybe somebody didn’t get radiation therapy, because it meant coming in many times a day for weeks and rather chose a different course of treatment. And you can see the treatment itself was changed most often in breast cancer.

So, this helps us as a center understand how COVID is impacting the care that we’re providing to our patients and, perhaps, come up with measures to mitigate those gaps.

Here we’re starting to look at differences by patient demographics, because it is important both at the national level and at the local level to understand, are some of these impacts effecting parts of our patient populations differently? So, we looked at by cancer type.

This is information comparing white patients to non-white patients. And we combine non-white, because we have many different groups that have small numbers and we wanted to understand as a whole what they looked like.

Sure enough, you see some of these differences where, especially in breast and cervical cancer, again, we have a higher COVID-related impact. Remember, those cancer sites were on the delayed treatment. You see that treatment was more often delayed in non-white patients compared to the white patients.

Now, is this statistically significant? We didn’t test for that. But here we’re trying to understand the patterns locally, so that we can intervene.

At the national level, once we aggregate data, we’ll be able to test for significance. Although, I would argue statistical significance is not the point of these data analyses. I think Dr. Winn would agree with me. I think he nodded in my peripheral vision; right?

We wanted to understand the differences so we can intervene. It doesn’t matter if they’re statistically significant or not. They’re present and we need to address them to ensure equity in our communities.

We haven’t talked about ethnicity yet today, but these are the same data by ethnicity, where we see similarly, by race, the Hispanic patients were more likely to have a COVID-related treatment impact, particularly in breast and cervical cancer, than the non-Hispanic patients.