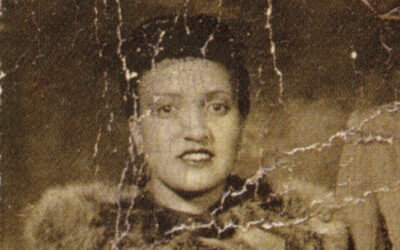

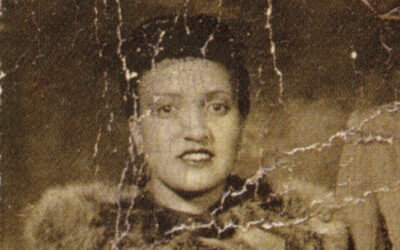

Henrietta Lacks, a mother of five, received cervical cancer treatment from Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1951. At the time, Hopkins was one of few hospitals that treated Black patients like Lacks.

During a biopsy, researchers collected cervical cancer cells from Lacks without her knowledge or consent. Her cells, later called HeLa cells, created the first cell line used in research for scientific breakthroughs—vaccines for the human papillomavirus and polio, drugs for HIV/AIDS, treatments for cancer and Parkinson’s, and COVID-19 research.

Lacks’s race and her role in the development in HeLa cell lines were not widely acknowledged until recent years. Now, researchers, medical societies, institutions, and members of the government are looking to preserve her legacy.

Honoring the contributions of Henrietta Lacks

- WHO Director-General Grants Posthumous Award to Henrietta Lacks

By ASCO | Sept. 21, 2022

World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus honored the late Henrietta Lacks with a WHO Director-General’s award, recognizing her world-changing legacy. Ms. Lacks, a Black American woman, died of cervical cancer 71 years ago, on Oct. 4, 1951.

While she sought treatment, researchers took biopsies from Mrs. Lacks’s body without her knowledge or consent. Her cells became the first “immortal” cell line and have allowed for incalculable scientific breakthroughs such as the human papillomavirus vaccine, the polio vaccine, drugs for human immunodeficiency virus and cancers, and, most recently, critical COVID-19 research.

However, the global scientific community once hid Henrietta Lacks’s race and her real story, a historic wrong that WHO’s recognition seeks to heal. “In honoring Henrietta Lacks, WHO acknowledges the importance of reckoning with past scientific injustices and advancing racial equity in health and science,” said Dr. Ghebreyesus. “It’s also an opportunity to recognize women—particularly women of color—who have made incredible but often unseen contributions to medical science.”

The award was received at the WHO office in Geneva by Lawrence Lacks, Mrs. Lacks’s 87-year-old son. He is one of the last living relatives who personally knew her. Mr. Lacks was accompanied by several of Henrietta Lacks’s grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and other family members.

“We are moved to receive this historic recognition of my mother, Henrietta Lacks—honoring who she was as a remarkable woman and the lasting impact of her ‘HeLa’ cells. My mother’s contributions, once hidden, are now being rightfully honored for their global impact,” said Mr. Lacks. “My mother was a pioneer in life, giving back to her community, helping others live a better life, and caring for others. In death, she continues to help the world. Her legacy lives on in us, and we thank you for saying her name—Henrietta Lacks.”

- U.S. government passes law honoring legacy of Henrietta Lacks by increasing access to clinical trials

By The Cancer Letter | Jan. 8, 2021

Congress passed legislation aimed at improving access to clinical trials for communities of color and decreasing health disparities. The bill was signed by the president Jan. 5.

The Henrietta Lacks Enhancing Cancer Research Act works to increase access and remove barriers to participation in federally sponsored cancer clinical trials among communities that are traditionally underrepresented.

The bill is named after a Black woman who died from cervical cancer and whose cells, taken without her knowledge or consent during her treatment, have been used to develop some of modern medicine’s most important breakthroughs, including the development of the polio vaccine and treatments for cancer, HIV/AIDS and Parkinson’s disease.

“ACS CAN is pleased to see this important bill, which is aimed at doing just that, pass in the Senate. Henrietta Lacks’ cells have saved countless lives and with this bill, her legacy will continue to improve health outcomes and reduce health disparities for countless more,” American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network President Lisa Lacasse said in a statement.

The law directs the federal government to study policies that impact diverse participation in federally sponsored cancer clinical trials nationwide and recommend potential policy changes that would reduce barriers and make it easier for patients from diverse backgrounds to enroll in clinical trials.

Quote of the week

My mother was a pioneer in life, giving back to her community, helping others live a better life, and caring for others. In death, she continues to help the world. Her legacy lives on in us, and we thank you for saying her name—Henrietta Lacks.

Lawrence Lacks

Recent contributions

- Historic Discovery of ThPOK Gene Honored in Journal Retrospective

By Fox Chase Cancer Center | Sept. 22, 2022

The white blood cells called T-cells play a critical role in immune function. However, for many years, scientists didn’t know why these cells divided into so-called CD8 “killer” T-cells, which fight and destroy pathogens, and CD4 “helper” T-cells, which play a supporting role by triggering the body’s wider immune response.

Then a discovery in 1997 by Dietmar J. Kappes, PhD, director of the Transgenic Mouse Facility at Fox Chase Cancer Center, solved that mystery, laying the foundation for a generation of research and new therapies in immunology.

Kappes’ discovery that ThPOK plays a critical role in the division of T-cells became the subject of a historical retrospective in a “Pillars of Immunology” article that appeared in The Journal of Immunology.

- FDA Approves First CAR T-Cell Therapy for Pediatric and Young Adult Patients With B-Cell Precursor ALL

By ASCO | Sept. 22, 2022

Originally published Aug 30, 2017.

FDA issued what it has called a “historic action,” making the first gene therapy available in the United States. The FDA approved tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) for certain pediatric and young adult patients with a form of acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

“We’re entering a new frontier in medical innovation with the ability to reprogram a patient’s own cells to attack a deadly cancer,” said FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb. “New technologies such as gene and cell therapies hold out the potential to transform medicine and create an inflection point in our ability to treat and even cure many intractable illnesses.”

Tisagenlecleucel, a cell-based gene therapy, is approved in the United States for the treatment of patients up to 25 years of age with B-cell precursor ALL that is refractory or in second or later relapse.

- Video: Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey Celebrates its 15th Anniversary

By Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey | Sept. 19, 2022

Roger Strair and Jacqueline Manago from Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey are featured in the Health Watch segment focusing on 15 years of patient care at Rutgers Cancer Institute.

Also featured are Rutgers Cancer Institute’s first bone-marrow transplant patient and a stage four, non-Hodgkins lymphoma patient who has created an annual bike ride that raises thousands of dollars for research done in the Strair lab.

This column features the latest posts to the Cancer History Project by our growing list of contributors.

The Cancer History Project is a free, web-based, collaborative resource intended to mark the 50th anniversary of the National Cancer Act and designed to continue in perpetuity. The objective is to assemble a robust collection of historical documents and make them freely available.

Access to the Cancer History Project is open to the public at CancerHistoryProject.com. You can also follow us on Twitter at @CancerHistProj, or follow our podcast.

Is your institution a contributor to the Cancer History Project? Eligible institutions include cancer centers, advocacy groups, professional societies, pharmaceutical companies, and key organizations in oncology.

To apply to become a contributor, please contact admin@cancerhistoryproject.com.