Last November, the American public voted on America First causes, which include the greatest scientific discovery and achievement enterprise in the world: The National Institutes of Health. NIH has made America first in biomedical science for the past century.

NIH was founded in 1887 with an initial budget of $464,000, and has been located since 1938 in Bethesda, MD. The National Cancer Institute has recorded budget allocations going back to 1938.

NIH budget from 1938-1960

NIH and NCI budgets from 1960-1993

NIH and NCI funding since the 1930s

The budgets for NIH have steadily increased since 1938, reflecting its national importance. From the 1940s to 1980, the budget at least doubled every five to 10 years, with more than a thousand-fold increase between 1940 and 1962, and a more than ten-fold increase (i.e., doubled approximately every seven years) from 1960 to 1983.

From the 1940s until 1970, the NCI budget had some increases, but didn’t always keep pace with the NIH budget, even before new institutes were formed (the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in 1950, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in 1954, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences in 1966, among others).

On Dec. 23, 1971, the National Cancer Act was signed by President Richard Nixon to create a national cancer program and advisory boards. We must remember the contributions of Mary Lasker, who was a philanthropist and activist for decades before the pivotal historic events of 1971.

She famously said, “If you think research is expensive, try disease.” U.S. healthcare spending grew 7.5% in 2023, reaching $4.9 trillion or $14,570 per person. As a share of the nation’s gross domestic product, health spending accounted for 17.6%.

Mary Lasker reminds us of the value of wealth and goodwill, features of the current Trump administration that are very relevant here. Indeed, science and cancer research are part of “American exceptionalism through technological superiority and economic dominance.”

Both NIH and NCI budgets increased during the early 1970s.

It is of interest that in 1966 the NCI budget was 12.95% of the NIH budget, and at the time of the 1971 National Cancer Act, the NCI budget was 16.1% of the NIH budget. By 1976, the NCI budget was at a new peak since the 1950s of 25% of the NIH budget. This may be due to the National Cancer Act. Of note, in 1976, NIH had the following institutes, with few formed after that time:

- National Cancer Institute;

- National Eye Institute;

- The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute;

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases;

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development;

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research;

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases;

- The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences;

- National Institute of General Medical Sciences;

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; and

- National Institute on Aging.

NCI in 1976

A small detour uncovered some interesting history as archived in 1976: 360,472 people died of cancer in the U.S. that year, and there were 18 NCI-supported Comprehensive Cancer Centers in the U.S. In 2025, the American Cancer Society predicts that 618,120 people will die of cancer in the U.S.

Historical landmarks include: Aug. 5, 1937, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the first National Cancer Act; Nov. 9, 1937, when the National Advisory Cancer Council held its first meeting; July 1, 1947, when NCI reorganized to provide an expanded program; intramural cancer research, cancer research grants, and cancer control activities.

By 1953, NCI had a full-scale clinical research program in the new clinical center. In October 1971, President Nixon converted the U.S. Army’s former biological warfare facilities at Fort Detrick, MD, to research the causes, treatment, and prevention of cancer. By 1972, a contract was awarded for the maintenance and operations of the Frederick Cancer Research Center at Fort Detrick, MD.

There is much detail about the organization of NCI and its budget in the 1976 NCI Fact Book. The components of the NCI org chart from 1976 reflect what has been in place for 50 years, including the divisional structure, advisory committees, Frederick Cancer Research Center, etc.

Significant thought, care, and justification should be taken in altering anything that has been in place for many decades, and a crown jewel and national resource such as the NCI warrants particular care. The goal should be to carefully preserve what has been working well. America First and American exceptionalism warrant nothing less.

Cancer centers and NCI peer review

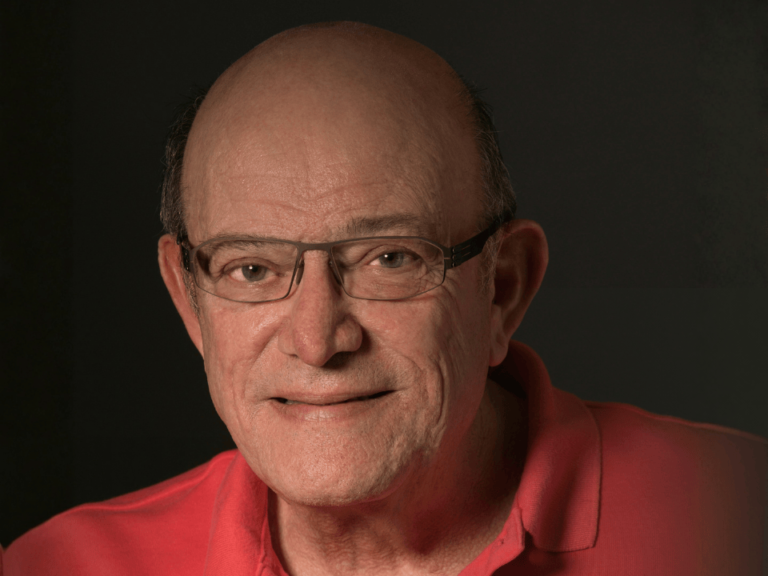

As a cancer center director and a scientific reviewer with NCI since 1998, I have come to appreciate both the Cancer Centers Program and the NIH peer review process.

Over the past two decades, the lack of sufficient NIH/NCI resources has increasingly created a toxic environment in the field, and in some ways, has poisoned peer review.

Having participated in at least 15 NCI Cancer Center Support Grant site visits during my career—and P01 site visits when they were still conducted—and having chaired numerous NCI study sections reviewing R01/R21, P01, and/or SPORE grants, I can say that NCI’s constructive peer review process, second to none in the world, has guided progress at our nation’s premiere cancer research institutions.

Patients do much better and survive longer when treated at NCI-designated cancer centers because every new breakthrough is tested there and is available there to help patients.

The prized NCI-designated cancer centers have been making America First for decades.

Our greatest academic centers and cancer centers in the U.S. have treated the most complex cases of cancer—as well as the world’s leaders or others who could afford it who came here for health care and cancer care—because there was nowhere else to turn for hope.

That is a testament to America’s leadership and impact of its scientific apparatus.

Strategic thinking at NCI goes way back

Strategic thinking and approaches in research and cancer control were put in place at NCI 50 years ago. While they were labeled differently, concepts of cancer interception were depicted, i.e. the prevention of transformation to cancer, prevention of the advancement of preneoplastic precancer, or prevention of metastases.

Both survivorship and palliative care were clearly on the minds of the leaders of the National Cancer Program in 1976. Under the Division of Cancer Treatment, there was active conduct of cancer clinical investigation of new therapeutic agents.

As someone who has been supported continuously by NCI R01 grants since 1998 (along with other NCI investigator-initiated research grants), it caught my attention that investigator-initiated support and investigator-initiated “regular research grants” represented 42.7% and 16.9%, respectively, of the NCI budget in 1976.

A recent article in the ASCO Post authored by Richard Boxer entitled “The Future Priorities of the National Cancer Institute” indicated: “In 2021, the NCI spent 42.3% of its $7.3 billion budget on more than 5,000 research project grants.”

A smaller slice for NCI over 50 years

NCI % of NIH Budget 1939 – 2025

By 1990, the NCI budget was 17.7% of the NIH budget, and by 2000, it was 15.7%. Over the past two decades (2005 to 2025), the NCI budget has accounted for 13-14% of the NIH budget.

The NCI portion of the NIH budget has been declining for 50 years, since the boost from 1971 (at the time of the National Cancer Act), when it was 16.1% of the NIH budget to 25% in 1976.

ROI and accountability

The age-adjusted incidence of cancer in individuals aged ≥ 55 years by diagnosis year during 1975-2019

It is also clear from data published by Springer Nature in an article titled “Trends in the incidence and survival of cancer in individuals aged 55 years and older in the United States, 1975–2019,” that there has been no reduction in cancer incidence in those over 55 from the incidence rate per 100,000 observed in 1975.

It is now well-known that cancer incidence rates are rising among younger individuals (younger than 50) and this has been ongoing for more than two decades.

Why hasn’t there been more impact on the basic cancer statistics?

It is not that the U.S. has fallen behind any other country. There has been impact, for example, from fewer people smoking: A lowering of cancer incidence rates for those over 55 since the 1990s. But we are no better as far as cancer incidence rates from 50 years ago.

In part, this is because cancer is complex, representing hundreds of rare or not so rare diseases.

We have learned much about cancer as far as its complexity, heterogeneity, evolution, environmental, genetic causes, and associations, with worse outcomes among the poor. But we haven’t implemented sufficient basic interventions as suggested by ACS in the past few years.

We have yet to fully realize the fruits of genomic medicine or the utility of AI.

Precision oncology

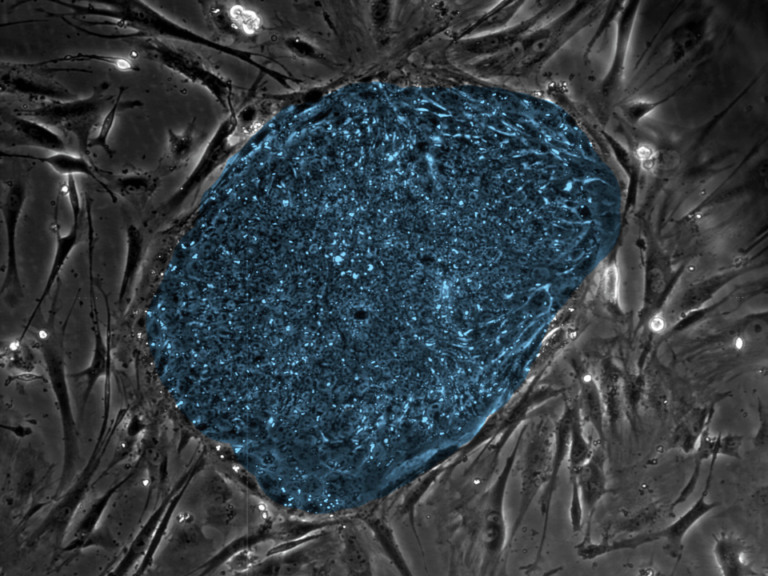

While we now have much technology for biomedical research, including single cell analysis, mouse models, the Human Tumor Atlas, liquid biopsies, and all kinds of omics and genomics aided by AI algorithms, the translation is lagging.

The dream of precision oncology is yet to be realized and many challenges to doing so remain. Precision oncology is the future of oncology. The U.S. has led and can continue to lead in this important area.

It was good to hear the recently appointed director of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Vinay Prasad, state publicly that randomized clinical trials may not be appropriate pre-approval for rare diseases. RCTs are similarly challenging in precision oncology (again, the future of oncology), where real-world control arms are useful.

Prasad was quick to pass judgement on a whole field by declaring in 2016 that “precision oncology has not been shown to work, and perhaps it never will” in Nature (“Perspective: The precision-oncology illusion”). This was met with a quick rebuttal by Abrahams and Eck “Precision oncology is not an illusion” and by Subbiah and Kurzrock “Debunking the Delusion That Precision Oncology is an Illusion.”

In 2025, there are many examples of precision therapy in oncology and many opportunities yet to come. An open-mindedness by regulators, a willingness to cooperate by big pharma, and more understanding and accountability by insurers is needed.

It may take 20 more years for precision oncology to be very mainstream, or it may take much less time. We can make a choice to embrace the fruits of science in medicine and lead the world.

Personal experiences and impact of NCI support

There is general awareness among cancer researchers and oncologists that our national investments in cancer research have been challenged for a generation.

Things were good in the late 1990s, and then the NIH budget doubled over five years, bringing much excitement and hope at the time.

I received my first R01 in 1998 while serving as a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. At the time, the payline at the NCI was above 20%, which was also when the “doubling of the NIH budget” was occurring through 2003.

Also at the time, NIH R01 grants were longer (25 pages instead of the current 12 pages), but one didn’t have to write 10 to 20 grants or revisions to be competitively funded to do research.

Government research grants are not entitlement programs. They are very competitive, and they get a great deal of oversight on deliverables. For decades, getting an NIH R01 grant has meant that an investigator was a leader in a certain area and was recognized nationally by the NIH study section, made up of peers who were also leaders in the field.

Evolution of the peer review process in an era of limited resources has not been helpful in some ways, and this requires reform. For example, de-emphasizing the “investigator” in review criteria is not a step in the right direction.

There are lots of unfunded mandates. Meanwhile, the modular budget has not changed in 25 years, and neither has the per diem rate for reviewers who spend numerous hours of personal time serving the NIH prior to and during review.

My first R01 came upon the discovery of TRAIL Death Receptor 5 as a p53 target gene. Discoveries made over the last 25-plus years in my laboratory funded continuously by the NCI led to advances in understanding of our innate immune system and its links to tumor suppression, as well as the discovery of a small molecule known as TIC10/ONC201/Dordaviprone that has been shrinking aggressive brain tumors in patients with H3K27M mutations.

The drug has been on track for FDA approval since 2017, when clinical data started showing patient survival benefit. These discoveries and translation that has been helping patients would not have occurred without the NCI grants.

The current funding climate has been threatening to close many academic labs, including mine, which is currently at Brown University. And it’s not because we are not doing important work relevant to patients and their unmet needs.

For example, we recently demonstrated a strategy to mitigate severe radiation side effects to the lungs, skin, and esophagus in mouse models. NCI is not funding this research that addresses patient suffering, and is also relevant to national security and bioterrorism with demonstrating rescue from lethality of radiation.

NIH and NCI budgets from 1990-2025

Atrophy, abandonment, and neglect of NCI

It wasn’t until I dug out the data on the history of NIH and NCI funding going back to the 1930s that I realized that the doubling of the NIH budget had been occurring for decades before the doubling that started in 1998.

From 1975 through 2000, the NIH budget increased from $2.09 billion to $17.84 billion, while the NCI budget increased from $692 million to $3.31 billion.

During the doubling that contemporary investigators are aware of (1998 to 2003), the NIH budget increased from $13.674 billion to $27.167 billion, while the NCI budget increased from $2.547 billion to $4.592 billion.

The vast majority of contemporary NIH-funded investigators like me are largely unaware of the older 20th-century history of very strong investments in the NIH and NCI, including regular doublings for decades. These investments led to Nobel Prize-winning discoveries, lifesaving treatments, and global leadership in biomedical science, medicine, and oncology.

For the past 20 years, however, the picture of NIH and NCI funding has looked very different from the prior 65 years.

NIH Total Budget Obligations (FY2000-FY2026)

Figures in billions of USD; FY2026 shows proposed budget cut

Between 2005 and 2015, the NIH and NCI budgets were flat, and while there have been increases from 2016 to 2023, the pattern is quite different from prior decades. What is evident is that there has been less than a two-fold increase in the past 20 years, as compared to a doubling every seven years over many decades.

An alternative to a common belief

There is a commonly held narrative that with the doubling of the NIH budget from 1998 to 2003, the budget could not keep up with the expanded workforce.

There is, however, an alternative explanation: The problem is not that the workforce has increased. The problem is that the budget has failed to be increased, as had been happening regularly for more than six decades.

Based on the analysis, there are two very concerning issues facing the scientific community, including the cancer research community in 2025 with current budget proposals.

The first is that if the NIH budget is reduced to $27 billion, as the administration has indicated is the intent, this takes U.S. science back to 2003 and that doesn’t account for inflation.

In addition, when adjusted for inflation, the NIH budget allocation has been essentially flat for 20 years, despite modest increases over the last few years. The current proposed $27 billion budget, if adjusted for inflation, is essentially equivalent to $14 billion in 2005 dollars.

NIH Appropriations

This is tragic.

Need for Trump’s bold, disruptive, and transformational leadership

It will take bold, disruptive, and transformational leadership such as America First to address the atrophy, abandonment, and neglect of U.S. science funding by the government for more than two decades.

It is only by understanding the history going back 85-plus years that words like atrophy, abandonment, and neglect can be appreciated.

For many veterans in science, we have spent most of our careers in a current system that has become increasingly toxic due to resource limitations. From personal experience over the last 10 years of cancer research, 31 grants submitted to NIH (some multiple times) were rejected and/or not discussed.

This involved many thousands of pages, thousands of hours spent, and careers affected. The system badly needs reform, because I know we can do much better than this as a society.

Also, from personal experience, it is disheartening in a different way to live in an underserved state with high cancer rates and a shortage of primary care and experts in oncology—and not being able to effectively address it.

The Legorreta Cancer Center, which I lead, has tried to bring an NCI K12 Calabresi Award to train clinical oncology investigators since 2020.

Paul Calabresi, a pioneer in cancer therapeutics, was a statesman in the field of oncology, past ASCO president, member of National Academy of Medicine, and a leader at Brown University for more than two decades.

The score improved from the 40s to the 20s over the years. On the first submission, one reviewer gave the grant a perfect 1.0 score in all categories.

In 2025, we have been left with no hope by NCI for funding, no plan to advocate given the current budget, but with reassurances that NCI leadership will, with confidence, work to balance many priorities, including training.

What could have been and should be, really

Had increases in the NIH budget over the last 20 years mirrored what had been happening for the prior six-plus decades, this is what we could have expected.

In 2003, the NIH budget was $27 billion. In the years before 2025, the NIH budget should have doubled three times (to $216 billion).

Similarly, in 2003, the NCI budget was $4.592 billion. In the years before 2025, the NCI budget should have doubled three times (to $36.7 billion).

For many veterans in science, we have spent most of our careers in a current system that has become increasingly toxic due to resource limitations.

It has been clear to me for some time that the budget of the NCI should be somewhere between $25 billion and $50 billion, and I have mentioned this to colleagues in the field.

The calculations about what should have happened are entirely consistent with what was expected. The resources of the U.S. government have grown steadily and exceed $4 trillion.

These revenues have been increasing steadily over the last 50 years. It is therefore inexplicable what happened over the last 20 years as far as government funding for science.

It is important to recognize that a current very big elephant is that even if the 40% reduction in NIH budget is somehow avoided, the lack of investment for two decades puts the U.S. behind.

The Trump administration can address this to ensure America First has a fighting chance in the world of science and cancer research.

What has to be dealt with first

In the current climate, it is very clear the government will not increase spending on U.S. science because of the perception that there is much waste, inefficiency, as well as corruption, fraud, and misconduct.

Most reasonable people would agree these problems must be addressed before advocating to increase U.S. taxpayer spending for NIH to fund science.

While inefficiency and waste certainly need to be reduced or eliminated, there is a consensus within the scientific and medical communities that a certain subject-matter expertise is required to surgically or precisely correct waste and inefficiency.

There is a reproducibility crisis in the minds of many people. There is a great deal of variability in biology that contributes to difficulties in reproducing some published results.

I personally reject the conclusion that most science is irreproducible, flawed, or that the funding pressures scientists face contribute in any substantive way to widespread misconduct.

This is offensive to science and scientists and damages public perceptions of science and scientists.

Scientific truth always reproduces. What doesn’t reproduce quickly goes by the wayside and is usually well known within specific fields. Anything important is followed up by others and if it doesn’t reproduce or is very variable as part of biology then it becomes less significant and, again, doesn’t get very far.

Fraud doesn’t reproduce. Government funding should be focused on innovative research while other strategies are used to address fraud. I don’t think fraud is as prevalent as some with unclear agendas would like the public to believe.

I also don’t think taxpayer dollars should be used to fund derivative pharma trials looking at dose optimization. I think pharma should fund that type of clinical research on their products while taxpayer dollars support truly innovative research.

I don’t want to see government funding get wasted on some of the things being advocated for. I strongly hold these views for many reasons.

Pharma’s influence, role, accountability, collaboration

There is real ongoing danger from conflicts of interest with pharmaceutical influence and control over clinical trials.

This too must be addressed, as does the issue of how pharma exploits academia by benefiting from innovation and discovery with little investment in academic research, education, and training.

It is important for the NIH and NCI to have more accountability to the public in terms of return on investment from taxpayer dollars. Special interests have for decades sucked away precious NIH/NCI resources.

It’s clear that we are not preventing or curing cancer to the desired extent.

This is where more accountability is needed. The bold, disruptive Trump administration is dealing with some of these issues. Pharma is not bad when there is alignment with common goals, less greed, and more collaboration.

NCI has orchestrated some honest broker activities for decades with pharma drugs through Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis and Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, but there is a need to conduct innovative, science-driven clinical trials to help patients.

Urgency of NCI’s mission

There is also a need to actively reduce the burden of cancer by understanding causes and developing cures.

We will not get there by defunding U.S. science and the workforce that has been challenged for more than two decades. Understanding U.S. government support over the last 85 years provides an important perspective on some of the current difficulties being faced and which have not yet been addressed by the Trump administration.

The administration can seize the moment in its efforts to restore greatness and global leadership in science.

While inefficiency and waste certainly need to be reduced or eliminated, there is a consensus within the scientific and medical communities that a certain subject-matter expertise is required to surgically or precisely correct waste and inefficiency.

We have global talent, much in the way of technologies, and a track record of the most Nobel Prize winning discoveries in the world, both as a result of NIH research and throughout academia in the U.S.

We must address an existential crisis in science that is also worsened by instability in government funding at the universities.

I would echo the concerns mentioned in the May 9, 2025 issue of The Cancer Letter, in particular with regard to addressing without further delay appointing the next director of NCI.

The chosen director will need to address the challenges through discussions with the Trump administration that clarify a long history of appropriately increased investments and emphasizes an exciting alignment of NCI’s goals with the newly elected government’s stated objectives to lead the world in biomedical advances.

The director must address the goals and advocate directly with the administration in the tradition of the NCI Bypass (Professional Judgement) Budget, which was established in recognition of cancer as a grave societal problem.

In my opinion, the Bypass Budget has not been effectively used in recent years, given where the current NCI budget should be based on historical trends. This must be addressed by any incoming NCI director working with the bold, transformative Trump administration.

Path to progress

To lead the world in science, technology, scientific discoveries, and medical breakthroughs, we must not forget lessons from the history of the NIH and NCI, and we should take great care in preserving, sustaining, and expanding the capabilities of NCI to address the burden of cancer.

The prized NCI-designated cancer centers have been making America First for decades.

The gap in government investments for over two decades has been eroding science, and this may have contributed to slipping life expectancy in the U.S. compared to the world’s most advanced nations.

We owe it to our ourselves and future generations to understand cancer causes from the environment, our diets, and our habits, and to realize the promise of precision oncology based on what we have learned in the past three decades.

These goals will reduce the cost of health care by precisely treating each patient with the right drugs.

I appreciate what the administration is doing to bring drug prices down, as well as efforts to pursue truth and academic freedom at NIH. Big Pharma can do much more towards societal good through collaboration with government, foundations, and universities.

Thinking big

The current administration prides itself on thinking big, which is great, and I fully agree with making sure that U.S. science leads the world in discoveries and cures.

It is time to do the right thing for cancer due to its broad impact on society. With ACS predictions of more than two million diagnoses and more than 600,000 deaths in 2025, and with nearly 20 million cancer survivors and their families, the impact of cancer is felt by voters among all political persuasions.

Patients with cancer, survivors, and advocates can work with the cancer research and oncology societies to make sure our elected officials in Congress and the White House hear this message.

The fight against cancer deserves much attention—with more investment.