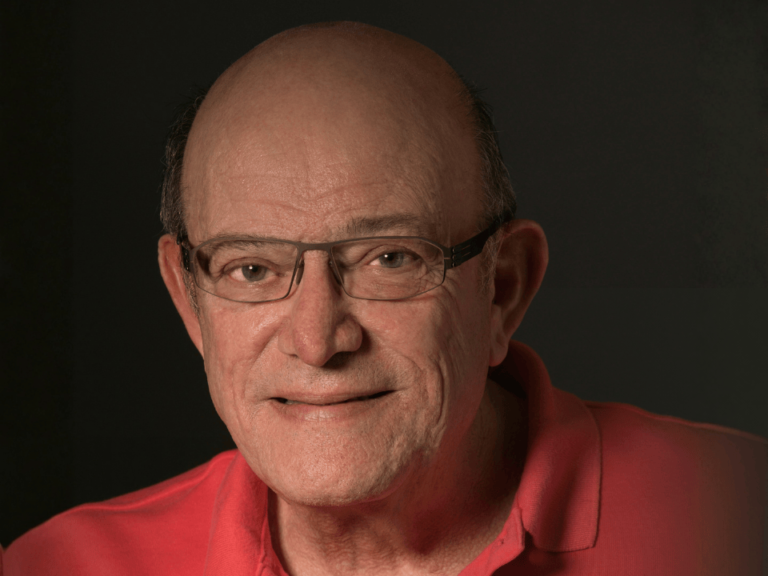

After nearly five years in the federal government—at both NCI and FDA—Ned Sharpless is stepping down from his position as NCI director.

“I feel like it’s a good time from a government calendar point of view to step aside and let someone else help lead the president’s new initiatives in this area,” Sharpless said to The Cancer Letter. “And I feel like it’s a good time for me personally, so it just felt like the right time.”

Sharpless was sworn in as the 15th director of NCI on Oct. 17, 2017, before becoming acting FDA commissioner for seven months in 2019. Prior to coming to NCI, he was director of UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center for four years (The Cancer Letter, June 16, 2017).

Sharpless is one of two directors to have served as NCI director and head of FDA, and the only one to resume NCI directorship after leaving FDA (The Cancer Letter, Dec. 6, 2019; Nov. 8, 2019).

“I call that the von Eschenbach Maneuver. I am one of two people to survive the NCI to FDA change. And I’m the only person to have performed the Reverse von Eschenbach Maneuver and come back,” Sharpless said. “It was a real kind of once-in-a-lifetime experience.”

At NCI, Sharpless has championed health equity; developed fundamental programs in data science, including the Childhood Cancer Data Initiative.

Sharpless advocated forcefully for policies to ensure continued support for investigator-initiated research in cancer and diversity in the cancer research workforce. Amid the calls for racial justice in the summer of 2020, he led the creation of NCI’s Equity and Inclusion Program (The Cancer Letter, Dec. 3, 2021; July 2, 2021; Oct. 9, 2020).

Sharpless aggressively pushed to increase NCI’s paylines, with a goal to achieve the 15th percentile by fiscal year 2025 (The Cancer Letter, April 1, 2022; Sept. 4, 2020; June 14, 2019).

Sharpless will continue as NCI director through April 29. NCI Principal Deputy Director Douglas R. Lowy will serve as NCI’s acting director effective April 30.

“Dr. Sharpless’ ability to manage complex problems has been invaluable to several NIH initiatives, including the agency’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and improving equity and inclusion, and in his role as chair of the NIH Clinical Center Governing Board,” NIH Acting Director Larry Tabak said in a statement. “Dr. Sharpless’s absence will surely be felt by his colleagues at NCI and beyond. But I have the utmost confidence in Doug Lowy’s leadership of NCI during this transition period. He is a seasoned and thoughtful leader who will guide the institute with a steady hand until a permanent director is appointed by the president.”

Lowy served as NCI’s acting director from April 2015 to October 2017, following the resignation of Harold Varmus and again in 2019 while Sharpless served as acting commissioner of FDA.

“The president’s goal of ending cancer as we know it today is grounded, in part, in the work of scientific discovery that Ned Sharpless has led at NCI,” Danielle Carnival, White House Cancer Moonshot Coordinator, said in a statement. “We have an audacious but achievable goal to reduce the cancer death rate by at least half in 25 years and improve the experience of all whose lives are impacted by cancer—working across government to develop and deploy additional ways to prevent, detect, and treat cancer—and Dr. Sharpless contributed greatly to that vision.”

“We have been fortunate to have Dr. Sharpless as director of the National Cancer Institute for the past four and a half years. I am especially grateful for his leadership of NCI’s contributions to the COVID-19 response and his work to minimize the negative effects of the pandemic on people with cancer,” U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra said in a statement. “He’s a true public servant, and I’m certain his work in the future will continue to serve the American people and ensure a brighter future for everyone affected by cancer.”

Sharpless said he is looking forward to taking a break, and, perhaps, rejoining academic oncology.

“I had always thought of myself as being a member of academia. I expect eventually, I’ll end up in an academic institution,” he said. “I liked doing that before, and I expect I might do that again.”

The next NCI director will be coming in at a crucial juncture for cancer research—with the reinvigorated Moonshot and a new DARPA-like Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health—which means that Sharpless’s successor must continue to provide cancer leadership with the Biden White House (The Cancer Letter, Feb. 18, Feb. 11, Feb. 4, 2022; April 9, Feb. 26, 2021).

“Oh, I think the next director will have a full plate. The NCI director’s office is very busy,” Sharpless said. “Were I a new director coming in tomorrow, I would think an important first job would be to try and figure out exactly what this administration’s plans are for the Moonshot 2.0, and for working with ARPA-H, the new federal agency.

“And so, I think understanding the White House’s priorities and what part the NCI is going to play will be really, really critical. And that’s why one of the reasons why I thought this was a congenial time for me to step aside, because rather than sort of do seven months of that planning period then have someone else take it over, it’s best I think for a new NCI director to be involved in that right from the start.”

In recent history, many NCI directors stayed on as administrations passed from Democrats to Republicans and back:

- Jimmy Carter’s appointee Vincent T. DeVita stayed on through both terms of the Reagan administration (The Cancer Letter, Dec. 7, 1979; Aug. 10, 1988).

- George H.W. Bush’s appointee Samuel Broder stayed on through the Clinton years (The Cancer Letter, Dec. 2, 1988; Dec. 22, 1994).

- Bill Clinton’s appointee Richard Klausner served nine months into George W. Bush’s first term (The Cancer Letter, July 28, 1995; Sept. 14, 2001).

- George W. Bush’s appointee John E. Niederhuber stayed on through nearly a year-and-a-half into Barack Obama’s first term (The Cancer Letter, Sept. 8, 2006; July 9, 2010).

Among Trump appointees, Sharpless was an anomaly. He is neither a libertarian nor a social conservative. His connection to the White House—and his appointment to the job of NCI director—came through Ronald DePinho, his lab chief at Harvard (The Cancer Letter, June 16, 2017).

The Trump administration named Sharpless to NCI in spite of his political giving. Federal Election Commission records show that Sharpless had made campaign contributions to Democrats, including a $250 contribution to the Obama-Biden ticket in 2008 and a $500 contribution to the Obama Victory Fund in 2012.

Sharpless spoke with Paul Goldberg and Matthew Ong of The Cancer Letter.

Paul Goldberg: I know that the NCI director job is not forever, and I think it was Harold Varmus who said that six years is about right. Why did you decide to step down, and why now?

Ned Sharpless: Well, I think it’s a real privilege and an honor to work at the National Cancer Institute, and it’s a wonderful job. The people are great, the work is great. The mission is great. I very much support and believe in what the present administration is trying to do in terms of cancer research. It’s the renewed commitment to do Moonshot and ending cancer as we know it. It’s a terrific time to be at the NCI and to be a cancer researcher.

But I’ve been doing it for a while. I understand why Harold said that, because it’s in some ways a challenging job. I think I’ve been running the National Cancer Institute at a particularly challenging moment where we’ve had, remember, an FDA sabbatical, and then we had this global pandemic that forced us to do an additional job while we were also trying to do our day job. And so, it felt like a good time to leave.

I’d like to spend a bit more time with my family, see my kids some. I have an elderly mother who broke her hip recently and needs a little bit of attention down in North Carolina, where my wife has been doing a lot of the elder care by herself, and I think she’d like my help with that.

I feel like it’s a good time from a government calendar point of view to step aside and let someone else help lead the president’s new initiatives in this area. And I feel like it’s a good time for me personally, so it just felt like the right time.

PG: Also, in terms of the president’s term, I think this may be the only opportunity for him to get anyone for any meaningful time; right?

NS: Right. As I said, there’s kind of an election calendar, and I hope and expect the administration to find an NCI director who is terrific and is deserving of this wonderful agency, and can help deliver on the president’s goals and missions. But people’s enthusiasm to do that would be somewhat dependent on the election calendar; I think it’s the right way to say it.

So, another issue is leaving the government when there’s sufficient time to have the best chance of finding another NCI director soon. And the other thing is, it didn’t feel like the right time to leave for the last two years, because I really didn’t want to leave in the middle of a global pandemic where we were trying to figure out how to run the National Cancer Institute.

But now that things are starting to get a bit more normal… Things are not normal, but things are getting a bit back to more of regular business, it felt like this was that window of time that would be best for the NCI and best for me.

Matthew Ong: What’s next for you? What will you do when you grow up?

NS: Thank you. I don’t know yet. My Number One commitment is to comply with federal law about looking for a job while I’m still a federal official. And so, that’s my real goal here. I envision something that involves a little bit of time to catch my breath.

The pandemic period in particular… Federal government’s busy at all times, but the period of the pandemic was almost like being a resident again. We worked these crazy hours on multiple projects, and weekends, and nights. The opportunity to kind of not have my cell phone go off at weird hours of the day for a little while is appealing.

I had always thought of myself as being a member of academia. I expect eventually, I’ll end up in an academic institution. I liked doing that before, and I expect I might do that again, but I have no immediate plans to join any particular institution.

I want to do the things that I really enjoyed prior to coming to government, which are working on great cancer science and basic biology of cancer and aging, and then also helping take these ideas and translating them for human use.

But I think the additional thing that might be new is I also have this new interest in public health and policy, and government, and science. And I expect I’ll find it tempting to write and think on those topics as well.

PG: Well, you’ve had, arguably, the greatest breadth of knowledge of any cancer institute director that I’ve covered—the overall understanding of the field, the grasp of it. What have you accomplished at the NCI that you are most proud of?

NS: Well, that’s nice of you to say, Paul. There’ve been some pretty smart NCI directors, so I’m not going to necessarily accept the premise of your question. But there are many things I’m proud of. A couple that come to mind, speaking about work at the NCI and not at the FDA, thought I’m also proud of some of the stuff we accomplished at the FDA.

At NCI, one item that I thought I knew a lot about, but I learned that I needed to learn more about when I came into federal government is the topic of pediatric cancer. When I got here, I was quickly exposed to some of the wonderful scientists in the intramural program and also some people in the advocacy community.

A supercharged Cancer Moonshot is just really timely. Because I think the quality science is there, the opportunity is there, and the need is there. So, I think the budget has been good while I’ve been here, but we still need additional support in cancer science.

My thinking on this topic evolved, and I really came to believe that we needed more of a national focus on childhood cancer, but it provides some research challenges, and the childhood cancers were all rare cancers. Therefore, that really led to the $500 million Childhood Cancer Data Initiative sort of beginning year three. And I think that getting that program launched and getting that focus has been very exciting…

And I think what we will learn from that effort in terms of how do you use data optimally so that you can learn from every patient will also translate well into adult cancer. Although we are starting in pediatric cancer, it’s not just the childhood cancer problem, it is really an approach to learning about cancer outcomes in the real world that I think will be useful across cancer research.

The events of the summer of 2020 and the murder of George Floyd forced the National Cancer Institute to take a look at our own workplace culture and what we are doing to promote health equity and racial justice in American society.

That’s not the NCI’s main job, but certainly cancer touches all aspects of society, and therefore it’s part of our job. And so, one of the things that I’m proud of is we launched a really vigorous equity inclusion program that is this sort of complex multi-committee structure that focuses on three areas.

One was promoting the right portfolios of cancer health disparities research. The NCI spends a lot of money on cancer health disparities research, but I think it’s fair to ask that we have the right portfolio and are we addressing the right questions? And are we doing it right, in essence?

The second topic was the topic of workforce diversity.

So, we took a long look at whom we fund and who gets grants from the NCI to do science, and does that workforce look like the population of Americans who get cancer? And the answer to that is in some ways, no, that there is underrepresentation of African-American and Hispanic scientists in the scientific workforce and in the caregiver workforce.

And are there things that the NCI can do through training or other measures to try and promote a more equitable scientific workforce?

And the third topic we took on is the NCI culture itself. While the NCI is a wonderful place to work, and it has this great mission of ending cancer suffering, it’s still true that when we started looking at our data, that we have issues of retention and promotion, and workforce satisfaction that we need to address.

And this is women in leadership, this is people of diverse race and ethnicity and leadership.

This is promotion and tenure, or retention rather. And so, these were a number of issues that I think we had to honestly assess through fairly vigorous data collection, and then try and address. And so, all three of those areas are ones where we develop a lot of focus, but it’s still, I think, areas where we have a ways to go.

Maybe another thing I’d mention is a strong commitment to investigator-initiated science. When I got here, the good news as we were just starting the Cancer Moonshot. The Cancer Moonshot, as you recall, was largely focused on translational science. And so, it had this sort of unanticipated effect, I think at that time unanticipated, that it really didn’t support a lot of investigator-initiated, what used to be called curiosity-driven science from the basic scientists who wanted to make progress in cancer.

Having been that kind of scientist myself, and having seen the impact those kinds of basic biological investigation can make for cancer research, I very much believed that we needed a strong, supportive investigator-initiated research, but a lot of our new money from the Moonshot was going to more translational stuff.

And so our paylines for investigator-initiated science had dropped.

And you’ll remember at one point, it was 8%. And I thought that was not good for cancer research, and certainly not good for junior scientists who wanted to come into cancer research. And so, we’ve worked hard to try and increase paylines, particularly for early-stage investigators, so they would see cancer research as a welcoming field.

So, this year, our paylines have gone all the way from 8% to 11%, which is still too low.

The 11th percentile is still very challenging. It’s a 35% increase or whatever, but that’s still not enough. But for early-stage investigators, they’re now as high as 16%.

So, I think those are steps in the right direction, although, obviously, I think there’s more to do in those areas. That means, in practical terms, that we’ve had to add on the order of over a period when our budget has increased like 13% since 2019, when we bottomed out at 8%.

We’ve increased the competing grants pool by on the order of almost 30%. So, we’re putting more money than we’re getting from Congress, on a percentage basis, into investigator-initiated science, the so-called RPG pool.

So, those are three areas. You have childhood cancer, health equity, and investigator-initiated science. But there are a lot of other things I’m proud of that I could talk about at length, but those are the ones that leap to mind.

MO: And that’s what my next question is about, really. You’ve steered the institute through the 2016 Moonshot, more recent budgetary challenges, COVID-19. And, as you said, you led the conversation on cancer disparities and on improving equity in the workforce. Is there anything you wish you could have done more of or have done differently?

NS: Well, I wish I could leave with paylines higher.

In fact, if you look at the Bypass Budget we’ve done for the last few years, we telegraphed the trajectory of getting to the 15th percentile by 2025, and that is not going to be possible. So, this year, if we’d kept up the trend that I was advocating for, we would’ve gotten to the 12th percentile. And looking honestly at the books, and really assessing, despite the numbers I quoted of putting like 25% of it in the RPG pool, it’s still not enough funding, because it’s very expensive.

We would have to get increases from Congress that have been larger than what we’ve had in the past. And this year’s budget, the 2022 budget, for the NCI is very good. We’re appreciative of the strong support we’ve got from Congress. It’s one of the best budgets we’ve had in a while. But despite that, supporting investigator-initiated science is really, really expensive.

So, it’s a deep disappointment to me that we won’t be able to reach the 12th percentile this year, but I believe it’s in the NCI’s best interest to stay flat at the 11 percentile and not give up on the goal—and still be very clear that the 11th percentile is too low, that should, with additional strong support from Congress, be possible in future years to go up to 12, 13, 14, 15 percentile.

Because those are the kinds of levels that we think are more sustainable for great cancer science.

And I know Doug Lowy, and many members of the NCI share that strong commitment to investigator-initiated science that is in the DNA of the NCI. And by the way, to be clear, investigator-initiated science is not just basic science, as I described, but really includes health services research and implementation science research. It means investigator-initiated, submitted by the outside scientists to the RPG pool. So, it really covers a lot of things that are very important for cancer progress.

So, that’s one thing I wish that had worked out a little differently.

The math is what it is, and we have to do 11 percentile this year, but I wish it could be higher. And I think 11% is still too low. Although, certainly, as I said, no one ahead at NCI has any business complaining about this year’s budget. It’s a good budget.

Should future years when the second version of the Moonshot or a supercharged Moonshot begins, I would hope that if that brings good support to the NCI, it would also include support that can help increase paylines. I think that’s an important future initiative for the National Cancer Institute. So, that’s one area where I wish we had things that worked out differently.

Another is, I wish things were a little more settled from the pandemic.

That’s again, nobody’s fault in particular, a global pandemic is a global pandemic. But I think all of us expected that we’d be back to “normal” by now, and that really hasn’t happened. And I think that what we’re seeing in the American workplace in general, and certainly in the federal government, is that things are going to be very different for a long time, and maybe permanently changed in terms of how we work.

But still, I think within federal government, things feel a little unsettled. It’s unclear how many days per week people are going to come in the office. It’s unclear what we can do by telework. It’s unclear these sorts of issues, and I wish they were more resolved.

Now, having said that, I think everyone at the National Cancer Institute has been surprised by how well things actually worked by telework, how able we were to review grants and disperse grants, and keep the mission of cancer science and cancer care going.

Nonetheless, I think that the balance of sort of in-person versus the virtual work is an unsettled issue that will be an interesting challenge for the NCI to work through over the next months and years.

MO: And speaking of the NCI budget and paylines, a lot of people are unhappy about the president’s fiscal year ’23 budget proposal. A lot of people are worried about ARPA-H potentially siphoning off money from NCI. What is your advice to the Biden administration? Do you have any thoughts about the latest budget proposal?

NS: Well, the president’s budget for ’23 is just out, and it includes what would be a reduction from the budget we got for ’22. I think I know why that happened, because a lot of the budgeting process occurred prior to this year’s budget being done. And I think OMB has a challenging job to plan for the future budget when the current budget isn’t known.

But I would say this president has made cancer a top priority of this administration. I think the president, first lady, and vice president have said every possible good thing we would want them to say about making cancer progress and cancer being a priority. It’s music to our ears to have a leadership that’s so committed to making progress for cancer. And I’m confident that this administration will support cancer science when it becomes time to do that.

As you know, the president’s budget is just a starting point, and a lot of things will happen before we enact funds for ’23 and out-years. The other thing I’ll say is that… one thing that I’ve been really impressed by, and is a nice thing I’ve learned about federal government is that there’s always a lot of partisan stuff going on, and there’s a lot of political drama at all times, and we live in a tumultuous time in that regard, but when it comes to cancer research, there’s broad bipartisan support for the NCI and for making progress in cancer.

When I go down and walk around Congress, I hear from leaders of all political stripes that cancer research is a top priority to the government. It’s a good use of federal monies. It’s something where we all want to see progress.

So, I think we have a lot of fans in Congress, and I think the president saying that cancer is a top priority and Congress wanting to support the National Cancer Institute is a good combination. I think that I have every confidence that the ’23 budget will be good for the NCI and that the supercharged Moonshot will happen, and that will be really good for the NCI.

PG: You’re one of only two NCI directors ever to have run both the Institute and FDA. What have you learned about how this town functions?

NS: You’re right. I call that the von Eschenbach Maneuver. I am one of two people to survive the NCI to FDA change. And I’m the only person to have performed the Reverse von Eschenbach Maneuver and come back.

I was tremendously grateful for Secretary Azar for asking me to do that. It was a real kind of once-in-a-lifetime experience, and I learned a tremendous amount and it was wonderful to get the opportunity to work with the talented people at the FDA.

And I really became a strong admirer of people like Janet Woodcock and Peter Marks, and Jeff Shuren and Mitch Zeller, and the other leaders at the FDA who were just wonderful colleagues, and really have this strong commitment to public health. And so, it was a fantastic experience.

I think I learned a lot about the things you would expect one to learn at the FDA, like how medical products are regulated, and how devices and drugs are approved, and what’s the difference between a drug and a biologic, and those kind things.

But I also found some of the other work of the FDA utterly fascinating, like the work of the animal center, protecting animal food, and animal antibiotics, and animal medicines. The Veterinary Medicine Center was really interesting.

And, for example, they have a really interesting problem to consider on how to regulate genetically engineered animals that are used for medical products and for food. And so, that’s a quite interesting scientific question. And then the work of the Tobacco Center is so important. This is really where the most important decisions in terms of national tobacco control occur.

And so, seeing the complexities of tobacco control and understanding the multiple sides of those issues and they really are interesting, but in Byzantinely complex legal issues related to tobacco regulation was very interesting and exciting. I learned a lot.

In short, to answer your question, I learned a lot about the role of a regulator in promoting public health and how that’s a really important role. It’s a much harder role to do than I think anybody would imagine, who hasn’t spent time at the FDA, and how grateful we should be as a nation that there’s such talented people that are willing to take this on.

I also learned that I’m a better fit for the NCI, I’m a scientist and a doctor, and not a lawyer or regulator. And so, I think my mindset is more NIH than FDA, but it was a real privilege and honor to get to work with those great colleagues.

PG: Actually the gods were very good to you by having you return to NCI before COVID hit.

NS: Yes, that was a fortunate development. I think it would’ve been a tough place to work during the pandemic. And I certainly keep up with many friends there, and heard what a challenging atmosphere—it was challenging everywhere in federal government, it was certainly challenging in NIH. But I think the FDA was particularly stressed, across the entire agency.

This was a big issue, not just for medical products and vaccines, but for the entire FDA. And so, I think in many ways, the timing was very fortunate. I think Otis Brawley told me I’m the luckiest oncologist alive, or something like that. And I didn’t disagree with him.

PG: I think the way he put it is that he, Otis, is the second luckiest, you are the first. He spoke about himself.

NS: No doubt, I have dodged a bullet in terms of trying to work at that job during that time that was very hard.

MO: What would the transition plan at NCI look like? Will Dr. Lowy be stepping in as acting director, and what kind of a person do you envision coming into this job on a permanent basis?

NS: I think the choice of an acting is up to White House and HHS. Doug has done a terrific job as acting NCI director twice before. Between Dr. Varmus and me, and then also when I was at FDA. And I think he would be an excellent choice to take over. And I believe that’s what will happen.

But I think the choice of who ultimately will be next NCI director probably will be made within the White House. And I suspect Francis Collins, as a senior advisor to the president, will have some role in that. I think Dr. Collins is a good person to be involved in this decision. He has a good scientific taste, and he knows the culture of the NIH and NCI really, really well. And I think we’ll look for a leader that can address some of the most challenging issues for the National Cancer Institute.

And so, I think some of those issues are related to clinical trials. Clinical trials are a real challenge at the present moment. The cost of clinical trials are increasing, the bureaucracy and oversight of clinical trials is scaling. I think a new director who understands things like the National Clinical Trials Network, and the management of a large complicated clinical trials network would be really advantageous.

I think we’re also in an era where we’re using data quite differently. And one major role of the National Cancer Institute is to aggregate these large data sets to make them available for search use. And that has a lot of challenging issues about data identification, and privacy, and security, as well as novel computational methods that are arcane. Who among us is an expert in artificial intelligence?

So, I think a sort of modern understanding of the opportunities for research that are provided by data use, novel data usage. Purely real-world evidence is also a real high priority for the NIH in general. And I think it would be a great thing for a new NCI director to have.

And I will tell you from being in this job now for the better part of five years, it’s important to the advocacy community to have an NCI director that really understands the issues that are important to cancer patients.

And so, as a medical oncologist, I think I’ve been focused on novel treatments, and on mortality, and incidents, and those are all super important. But I think also, the NCI director has to think about issues like survivorship, and financial toxicity, and access to high quality care. And these are places where the NCI has a role. We have a research role.

I mean, our mission is to understand why barriers to care exist, and are there things that we can do dismantle those barriers to care? Or understand why financial toxicity occurs, and are there things that can be done to minimize financial toxicity?

But those are really, really important research topics that I think an NCI director has to understand and has to be eager to work on.

PG: I’ve always wondered about this, and maybe it’s the right time to ask this question. There has not been a woman NCI director yet, and there has not been a person of color in the role of the NCI director. Meanwhile, there’s been a woman NIH director, for example, and many other institutes and centers. Do you have any thoughts on that?

NS: Well, you know what? On the 11th floor here of the Building 31 on NIH campus, there’s some portraits of all the former NCI directors. I guess if there’s a portrait of me up someday, it’ll be 15 white guys. It is true. It’s been all white men to date.

I think in some ways that’s a problem for the National Cancer Institute. Cancer affects everyone, including women and people who are not white. And so, the leadership of this institution should be as diverse as the American public.

I suspect that will factor into the decision making as well. This administration has talked about having diversity in leadership at all levels as being a high priority. And certainly, the president has talked about the extraordinary diversity of his cabinet and other leaders in government.

So, I think that it would be great for the NCI to have a female NCI director or an African American NCI director, or Hispanic NCI director, or an Asian NCI director. I think any diversity would be good for lots of reasons, not the least of which is that I just described how we’re spending so much effort to try and promote workforce diversity, in the scientific workforce, in the caregiver workforce directly related to cancer.

And it would be great if the NCI leadership should similarly exhibit diversity.

Now having said that, I will say that while the NCI director has been white men to date, the NCI has some significant diversity. We have a lot of women in leadership at the National Cancer Institute, and we have diversity in terms of race and ethnicity.

We can do better. I think it’s we’re not sufficiently diverse in those regards, but we have made some strides through recent years, but having this director be diverse would be I think a wonderful symbol.

PG: In recent years, the number of women cancer center directors has decreased, and what a way of letting the world know that this is a priority. There’s no reason for there not being more women cancer center directors that I can think of.

NS: I think hiring in these kinds of jobs is a complicated business, and is somewhat determined by the applicant pool and who’s willing to do the job, and can do the job, and these kinds of things.

I think most of the institutions, if not all, that we support, are really committed to diversity, but they have other reasons for who they pick for what job that they hire for.

And I can’t say for sure what will happen in federal government. I think Dr. Collins and the White House are committed to diversity in leadership both at the NIH and the NCI. And then we’re going to have an ARPA-H director, too. So, there’re a couple of new jobs in the federal government that are going to be highly visible.

But I know that that is an important consideration. And if there are qualified candidates, I would think they would give strong considerations to these roles.

MO: We’ve talked about the NCI budget at length, but here’s a final budget question. NCI budget has grown nicely during the past six years. Has it been enough money? We know the paylines need to go up, but how much is enough?

NS: Dr. Varmus told me NCI rather had a decade of flat budget in 2005 to 2015. And Harold was running NCI during that period, and he told me how challenging that was. And I certainly had a much more favorable funding environment since I’ve been here. And so, the budget’s increased every year I’ve been here.

Since 2015, it has grown in quite a remarkable way. In 2017, it might have been almost $450, $470 million increase, something like that. And then this year $350 million–very good years. But it’s not enough. And so, on the one hand, I want to be appreciative of the congressional support. I think as mentioned, we have some real champions in Congress. I’m grateful that they understand the importance of biomedical research.

But on the other hand, when you look at the size, the cost of cancer to the American public, it’s a disease alone that costs on the order of $200 billion a year to treat, and then you also add up the cost of lost productivity and missed work. And then you throw on top of that the tragedy of the burden of cancer on America. It’s incalculable. There’s no monetary assessment to how awful cancer’s burden is in terms of the tragedy it causes an American life.

It’s great to talk about ending cancer as we know it, that is so exhilarating and galvanizing to have that kind of leadership from the president. But the NCI is now going to be tasked with effecting that vision.

So, it’s a tremendously expensive problem. It’s a tremendously tragic problem. Therefore, the amount that we’re spending on it as a nation is modest, compared to the size of the problem. And maybe the last point I’d make about that is, I think we have really good evidence in the last few years to show that investments in cancer science and cancer care pay off. And that is that, if you invest in cancer research, eventually it leads to new therapies, and new drugs, and new devices, and new ways of preventing and diagnosing cancer that are valuable. So, we have a really documented success.

I’d have to look at the numbers, but 60, 70 new FDA approved small molecule and antibody drugs in the last couple of years since I’ve been at NCI. I can remember there were whole decades where we had only a handful of drugs that were really meaningful for cancer patients. And now we’re seeing this furious pace of new discovery and that’s just for therapeutics, but there’s also similar productivity and diagnostics, and even in prevention measures now, or early detection measures.

So, it’s a really exciting field, a really exciting time in cancer research. I think that the reason that’s happening today is because of these strong investments that the United States has made in cancer science since the 1980s, and that effort is now bearing fruit. I think there’s every evidence that cancer is a really expensive problem. It’s a national tragedy, and investments in cancer science will lead to meaningful improvements and outcomes. So, it’s a good use of federal monies.

And the proof that we don’t spend enough is our 11% payline and even lower paylines we have for some of our other grant mechanisms, like the SPORE program, a really wonderful scientific program that is way oversubscribed and too highly competitive. So, we know there are great scientific initiatives and great scientific programs that we’re not able to fund, that we’re not getting to because of our low paylines.

I think we have strong evidence that with more money, we could fund more great science. And I think Congress in a large part, and many members of Congress agree with that, the federal budget is a complex process that tips a lot of important things against each other.

But I think the president’s call to end cancer as we know it through renewed commitment of resources, through a supercharged Cancer Moonshot is just really timely. Because I think the quality science is there, the opportunity is there, and the need is there. So, I think the budget has been good while I’ve been here, but we still kind of need additional support in cancer science.

PG: Speaking of which, the 50th anniversary of the Cancer Act occurred on your watch. That must have been a very interesting time to be running the National Cancer Institute, and looking back at everything that has happened over 50 years.

NS: That was a really exciting and a wonderful experience. I think it was a lot of fun. I have sort of a personal interest in history, and so it was fun digging out some of these old black-and-white photographs. And rereading the National Cancer Act and trying to understand what was President Nixon thinking back in 1971.

And I did have the opportunity to speak to people like Vincent DeVita about the NCI years ago. And so, learning about the history of the National Cancer Institute, and the history of the National Cancer Program over the last 50 years, was really interesting to me personally. I think it was also great to see how the entire kind of cancer research community availed itself of this anniversary to sort of take stock of our progress.

The NCI was talking about it, and many of the cancer centers were talking about their work over the last few years. I loved the Cancer History Project The Cancer Letter put together to talk about some of these initiatives. And some of the well known stories, combination chemotherapy at the NCI, but also some of the much less well known stories that were so exciting about the last five decades.

But it was also a good time to celebrate the progress we’ve made, but to take on a stock and realize that although we have made a lot of progress in cancer, a much better understanding of cancer biology than we did even 20 years ago, and much more effective therapies, and much less toxic ways of treating people and ways of preventing cancer that we never really imagined.

Despite all that progress, we still have 600,000 Americans dying of cancer here in the United States. Cancer is a leading cause of death in children and young adults. It’s a highly morbid condition. It’s very expensive to treat. Often, the treatments are quite toxic. And we have a lot of preventable cancers where we just aren’t able to get effective prevention and screening measures out at the population level.

We still have a long way to go to end this tragedy, or minimize this tragedy, in American life. The 50th anniversary was both exhilarating to sort of look at the history and look at how far we’ve come, but it was also sobering to realize that despite all that effort, and all that work, and all that progress, we still have a really bad problem that needs our intense focus.

MO: What do you think the next director needs to do and focus on? Do you have any advice to pass on?

NS: Oh, I think the next director will have a full plate. The NCI director’s office is very busy. Were I a new director coming in tomorrow, I would think a very important first job would be to try and figure out exactly what this administration’s plans are for the Moonshot 2.0, and for working with ARPA-H, the new federal agency.

It’s great to talk about ending cancer as we know it, that is so exhilarating and galvanizing to have that kind of leadership from the president.

But the NCI is now going to be tasked with effecting that vision. We’ve talked a lot about mortality as a way to measure progress. And so, the president has said for example, that he would like to see a 50% reduction in cancer mortality in 25 years.

And mortality has the virtue of being a measurable and hard metric. But, certainly, it’s not the only meaningful metric, and there are lots of other things related to survivorship and clinical trials accrual and data aggregation.

And there are lots of other ways to sort of measure the productivity of what we’re doing in terms of cancer research and cancer care.

And so, I think understanding the White House’s priorities and what part the NCI is going to play will be really, really critical. And that’s why one of the reasons why I thought this was a congenial time for me to step aside, because rather than sort of do seven months of that planning period then have someone else take it over, it’s best I think for a new NCI director to be involved in that right from the start.

And to be fair, we’ve had a lot of work done on the Cancer Moonshot already, and we had this first successful event in February to kick things off. And then we had the Cancer Cabinet. But there’s still a lot of planning and new stuff to come, and how will we get advice from the extramural community, for example. And so, I think that will be the thing that a new NCI director will have to take on, and should take on right when they enter is how to integrate into the White House’s plans, and sort of supercharge the Moonshot as the president says.

So, I think that’s a great opportunity that’s exciting. I suspect anybody who’s interested in cancer research and cancer progress would be thrilled by the prospect of being involved in that. And I think that’s job one, but that’s like job one of 150. Because there are lots of other things that are really important, too, that need intense focus. And I could list them all, but I think that’s probably not in anyone’s best interests.

PG: What was also interesting about observing you in this job is that you have managed to stay mostly apolitical. You are a presidential appointee, and you’ve served through the change of administrations. Did you do this deliberately—stay out of politics? Is that something that just sort of came naturally?

NS: No, I would say that was deliberate. I’m a dyed-in-the-wool rabid moderate. But the fact about cancer is that it’s pretty nonpartisan, that everybody wants to see progress for patients with cancer, and everybody strongly supports the mission of the National Cancer Institute.

There is some disagreement about the best way to do that and what should the priorities be, and etc., etc. But I think the thing we can all agree on is that cancer is a national tragedy, and it’s an area where we all like to see progress, regardless of political stripes. It’s as challenging for the NCI director as it is for other leadership roles in government to stay out of politics.

But I think it’s really important to do that.

Certainly, my time at the FDA convinced me of that, because if you’re a public health official and your advice appears to be tainted by political considerations, then people won’t take your advice. And so, I think to be the best NCI director possible, one has to really stay out of politics, because the work of the National Cancer Institute is not partisan, and injecting politics in what we talk about won’t be useful.

And I think that’s generally true across public health entirely.

I’ve worked really hard to not be drawn into those kinds of issues. And as I said, because people on both sides of the aisle want to see progress in cancer, it’s easier to do that as NCI director. People in both parties are supportive of what we’re trying to do, and therefore the National Cancer Institute director doesn’t have some of the same political pressures that other parts of government have, even compared to the FDA commissioner.

MO: Did we miss anything?

NS: No. I want to thank you for the opportunity to speak, and for your great coverage of cancer-related issues throughout the years.