Twenty-five years ago, The Cancer Letter missed a big story.

On June 4,1996, Diana, Princess of Wales, swept into Chicago for a 48-hour visit to raise money for Northwestern University, Gilda’s Club, and the Royal Marsden Hospital, and all we did was run a paltry item in the “In Brief” section:

PRINCESS DIANA made opening remarks at a breast cancer symposium conducted by the Robert H. Lurie Cancer Center at Northwestern University on June 5. Her 48-hour visit to Chicago was expected to help raise more than $1 million for cancer research through ticket sales to a lunch and black-tie dinner. The funds are to be shared equally by the Lurie Center, the Royal Marsden Hospital of London, and Gilda’s Club, a New York-based ovarian cancer support group named for the late actress Gilda Radner. . . .

It wasn’t even the lead brief.

A tidbit about the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project’s successful re-competition of NCI grants for the chemoprevention and therapy was deemed more important and ran above it.

Yes, Norman Wolmark, chairman of NSABP, was prioritized above Diana, Princess of Wales. Of course, the Diana story was thoroughly covered by celebrity-oriented outlets, and all Norman had was The Cancer Letter.

To plot Diana’s Chicago visit on the timeline—for those watching the Netflix series The Crown—at the time the People’s Princess was separated from Prince Charles, but not yet divorced. She died in an automobile accident not quite a year and two months later, on Aug. 31, 1997.

One reminder of the 1996 visit is the Diana, Princess of Wales Professorship at Northwestern.

The chair was first held by Craig Jordan, whose research led to widespread utilization of tamoxifen for the treatment and reduction of risk of breast cancer.

In August 1998, days before the FDA Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee vote that resulted in approval of the risk reduction indication for tamoxifen, Jordan reflected on Diana’s visit:

“Diana being British, me being British, tamoxifen being a British drug; it’s the symmetry. [It was] like the planets aligned,” Jordan said to Chicago Tribune.

The Princess Diana chair at Northwestern is now held by Daniela E Matei, chief of reproductive science in medicine in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Northwestern.

In 2016, at Matei’s investiture as the Diana, Princess of Wales professor, Ann Lurie, president of Ann and Robert H. Lurie Foundation and Lurie Holdings Inc. recalled the day Diana came to town, inspiring her to establish the professorship.

“Back in 1996, I remember that Diana urged cancer researchers at Northwestern to avoid the other ‘c’ word—complacency—in their work. Today, we have adopted ‘urgency’ in its place,” Lurie said. “I am happy that through this professorship that exists in perpetuity I could help to leverage the recruitment of someone like Dr. Matei.”

I might as well just say it: I was the guy who screwed up by failing to do a proper story 25 years ago.

Accepting full responsibility for this failure of news judgment, I called Steven Rosen, former director of Northwestern University Lurie Cancer Center, who is now the provost and chief scientific officer at City of Hope and director of Beckman Research Institute.

Paul Goldberg: Like everyone else, I was watching The Crown, and then I thought, “Wait, wait, wait. Princess Diana did something at Northwestern.” And then I thought, “Why don’t I give Steve Rosen a call and ask about it.” So, how did this come about?

Steven Rosen: She was going through her marital issues, and she was tied to People magazine. Every time she was featured, they had more sales than ever before.

They had a unique relationship, and there was someone from People magazine who knew her. She felt like she had to leave London for a period of time, just to clear her head. The only way she could leave was to be involved in some sort of philanthropic activity.

And it was decided that it would be appropriate to come to the United States. Fergie had been to Chicago—I don’t know if they had dialogue, for a fundraising event for ALS prior to that.

What I heard from People magazine was their feeling was that New York would be too much pressure, Washington was too quiet, and Chicago would be ideal.

There was a connection between the editor of People magazine, who had been at Princeton University at some point and Henry Bienen, the president of Northwestern, who had been at Princeton.

Everything led to a discussion with People magazine of bringing her to Chicago for a fundraising event that would benefit her charity, which was the Royal Marsden and the People magazine’s charity, which was Gilda’s Club, which had been started not long before the visit. And then the Lurie Cancer Center would be the third component. And so, there was initial dialogue.

There was about six months of planning, and she, I believe, came in June for several days in 1996—25 years ago.

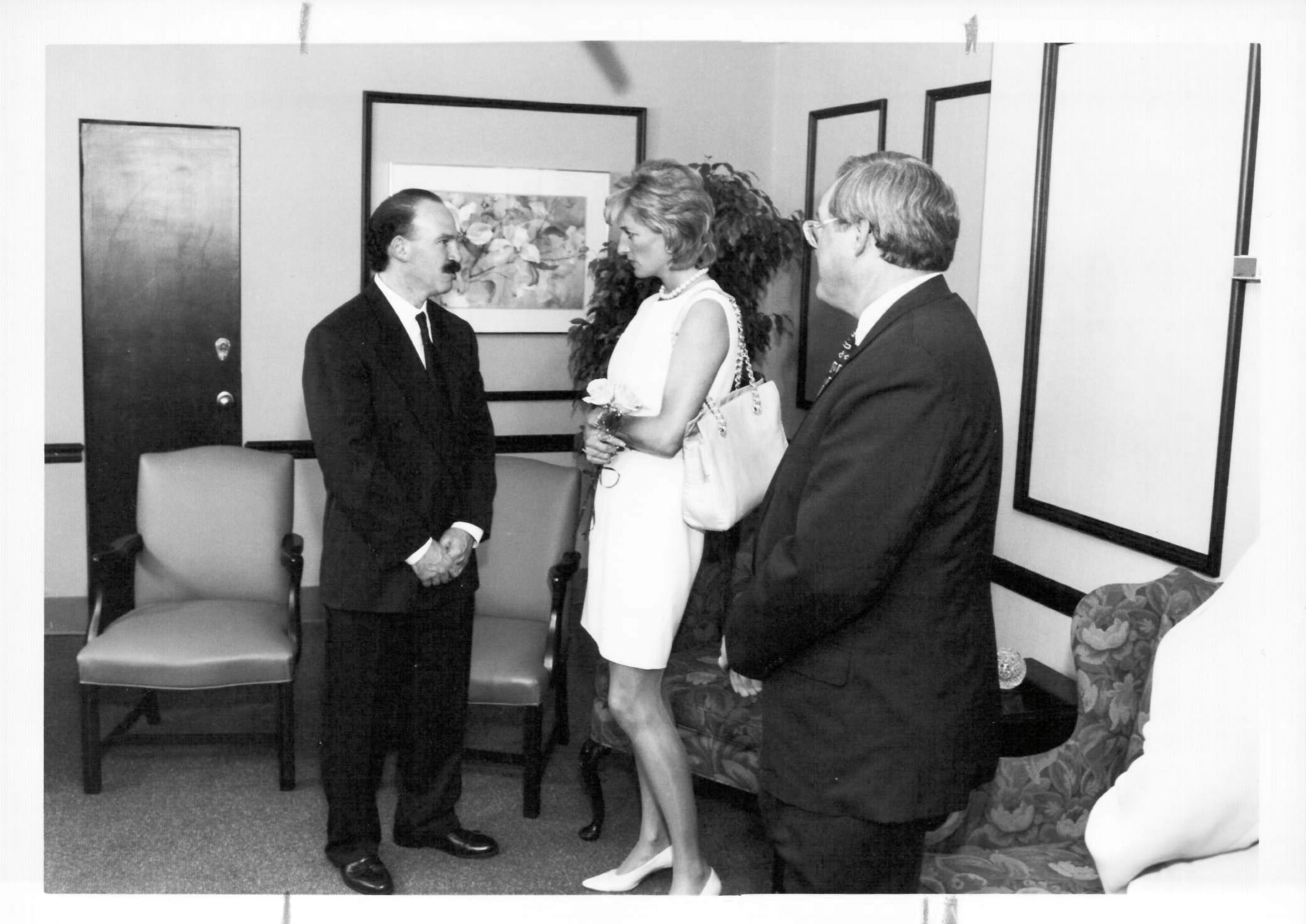

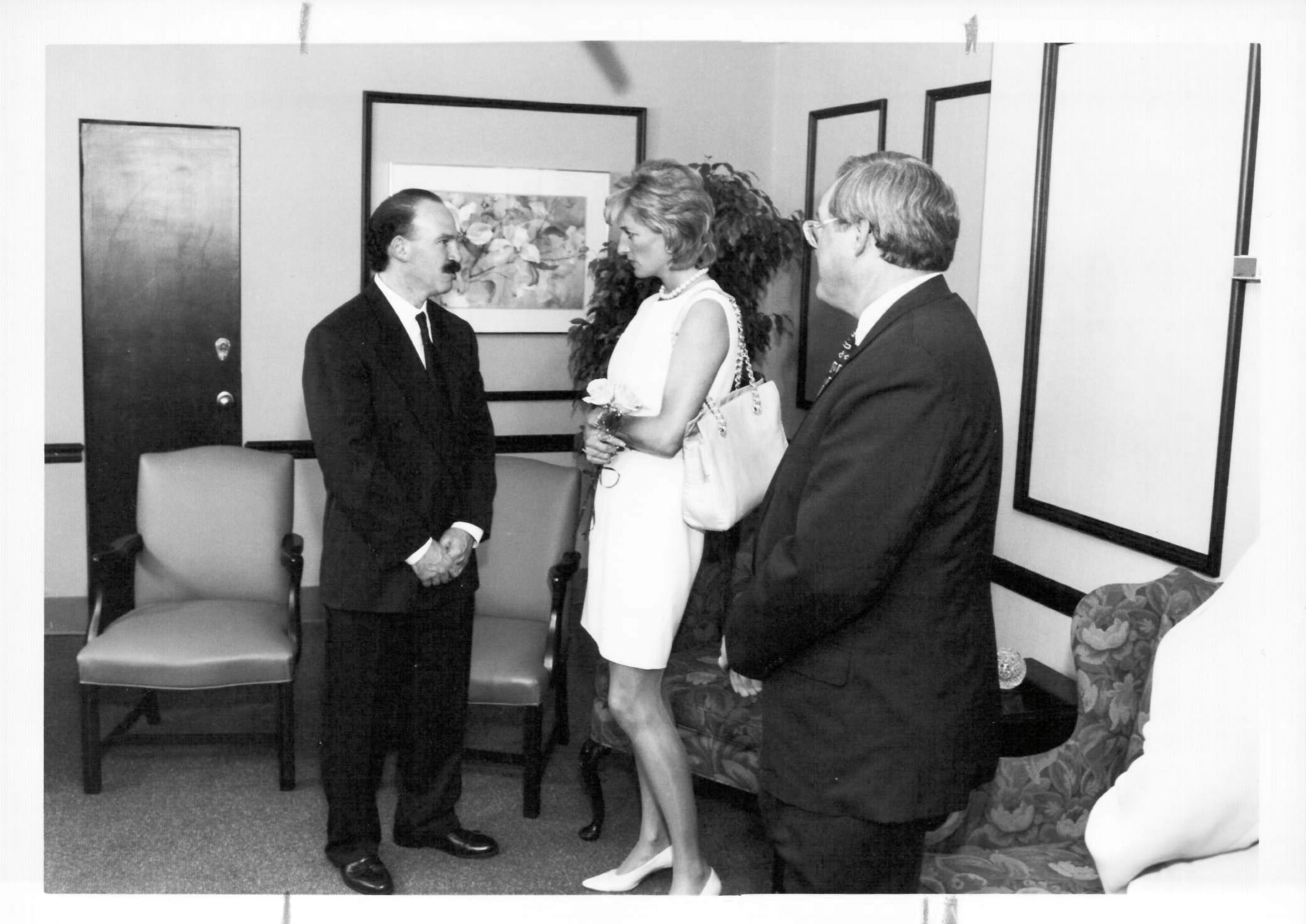

The first night, she came to President Bienen’s home in Evanston, at the university. And there were three separate rooms. One was for donors. One was for university officials. And the third was for those of us that were clinician-scientists that were going to participate in the internationally broadcast symposium focused on breast cancer.

The next day, she went to Cook County Hospital. She then came to Northwestern.

I took her on a personal tour of our hospice unit, and she was just very gracious. There was no media involved. She and I just walked from room to room, and she spent as much time as the families wanted, just meeting with her.

What was that like?

SR: It was magical. She had a great sense of humor. She was very down to earth. She had a natural kindness to her. And then that evening, there was a gala in her honor at the Field Museum, and Tony Bennett performed.

There were a number of celebrities there. She danced with [talk show host] Phil Donahue.

And even Michael Jordan’s mother came before one of his basketball games, which happened to be that evening, and brought some souvenirs. And I can’t recall the exact order, but there was also the symposium, which was quite remarkable.

The symposium was in the law school’s auditorium, and the room was filled to capacity. It was the hardest ticket to get. Many of the governors’ wives from around the country came.

They were invited by Governor [Jim] Edgar. At the time, he was the governor of Illinois. And I was the moderator of the program.

I know Craig Jordan participated. Nancy Brinker was part of it. Karen Antman was part of it.

And the most memorable part for me, obviously, I was a little nervous, but I was fine once I got on the stage, knowing the audience and the fact that it was being broadcast everywhere.

But when I sat down next to her, right before she was going to speak, her hands were trembling. And so, I just gently put my hand on her arm, and she sort of smiled. And then she got up and spoke more eloquently than anyone I’d ever seen in any program.

At a gala in her honor, Rosen was not eligible to dance with her because of their height discrepancy.

[Diana’s remarks, first published here, follow:

I would like to begin by expressing my sincere thanks for the invitation to attend this symposium here in Chicago. It is a great privilege to be amongst some of the world’s most eminent specialists in the field of cancer and to share in this conference with you—and I can only repeat my thanks for the invitation.

Today is an important opportunity to draw the world’s attention to the disease, because there are few subjects which are more likely to raise anxiety and fear than cancer—for some it remains the dreaded “C” word. Most of us have known people who have suffered terribly at the hands of this disease. It seems to strike out of nowhere, destroying lives almost at will, leaving devastation in its wake. Amongst all the diseases cancer has, justifiably, the very worst reputation.

And yet in the midst of such negative circumstances there is, today, an amazing amount of hope; yes, hope. Ladies and gentlemen, that hope is seated before our very eyes this morning. In so many of the seats before me I see specialists who bring hope, pioneers whose work will soon transform the lives of countless individuals bringing hope to those who might describe themselves as hopeless today.

The advances that have been made are quite staggering and, as we know, research and development continue apace. As president of The Royal Marsden Hospital and of its Cancer Fund, I have witnessed at first hand significant progress in the diagnosis, treatment, and management of patients which the hospital, in collaboration with colleagues here, has achieved through the exchange of scientific knowledge and advances in the care and support of cancer patients.

But our work is not yet finished. And so I would suggest that now might be a good time to consider another “C” word which may threaten us. It is the word complacency! And that is why this symposium is of such importance.

Whilst few of us may be able to pioneer a new form of surgery or test a new drug, we can support those who do. We can raise money for research and work in other ways to ensure that the fight against this disease continues to press ahead.

A few years ago I read an article in which the writer suggested that working in the field of cancer might be a very depressing task, since it mostly remains a terminal illness and continues to take the lives of millions of people. At the time I could see the logic of that writer’s viewpoint. And yet he may have missed the point.

It may not always be possible to provide the complete solution to a patient’s predicament–but does that mean we should give up? Sometimes we may only be able to provide support and counsel—does that mean we have failed? I think not.

In just a few weeks’ time this nation will be hosting the Olympic games. Almost 90 years ago perhaps the most famous Olympian, Pierre de Coubertin, said these words in a speech in London. We might ponder them as we consider the subject of cancer.

He said: “The most important thing in life is not the victory but the contest; the essential thing is not to have won but to have fought well.”

I wish you all the strength to continue in your most important work and promise that we will continue to support you.

Thank you.]

And she sat down, and there was, obviously, thunderous applause.

And then she whispered in my ear, “How did I do?”

I was thinking, “My God. You own the world. You own the planet.” And I didn’t appreciate prior to her visit, her… I knew very little about her and her celebrity status. I mean, obviously, I knew she was, but I wasn’t following the royal family very much.

We underestimated completely how much money we could raise. I think we raised about $1.5 million in a millisecond, but if we had recognized the power of her celebrity, we could have raised at least ten times that amount, if not more.

The last day, there was a luncheon at the Drake, where there were also featured speakers. It was quite a whirlwind three days that I’ll never forget. And then, obviously, the tragedy that followed—I think about six or nine months later, when she was in an auto accident and died.

I can still remember that like yesterday. I was sitting in Michigan and watching TV when the news came on.

The funny part about the visit was there were probably a thousand photographs taken.

This is pre-cellphone, and every photograph she looked perfect, but no one could find that picture they liked of themselves. It was really very cute.

And then she wrote me that beautiful letter, as you saw.

I remember running into you at ASCO after that. I’m pretty sure it was Chicago, and I said, “Hey, I’m really sorry to hear about this.” And you said, “Here we are. We got the comprehensive designation, and she wasn’t there to share the good news with.” Because you did get the comprehensive designation in that interim period. Right?

SR: Right. The core grant. We had gotten the core grant the cycle before. In those days, when you got the first grant, it was for three years, and then you went for renewal, and when we renewed it, we got comprehensive status.

I thought that during the visit you got to dance with her at one point. Did you?

SR: Actually, the funny part, or the embarrassment for me, they said that she couldn’t dance with anybody who was under five-ten, and I’m five-nine-and-a-half. So, they actually said on national TV that she won’t be dancing with me.

Was there any other highlight from her visits with patients? Anything that comes to mind?

SR: Just her sincerity and the fact that she was able to dialogue so effectively with people from every walk of life. There was a mixture. The other part that’s probably the most profound, the hospice unit at Northwestern, one of the first in the nation—ASCO’s Jamie Von Roenn was the inaugural director.

They had decided that they were going to close the hospice unit for financial reasons. Then, Diana decided she wanted to visit the hospice unit. Not only didn’t they close it, but they refurbished it.

Any other thoughts?

SR: Just that we need more Princess Dianas.

We need people who have that celebrity status, that power. They are capable of doing so much if they direct it in a meaningful way as she did.