This story is part of The Cancer Letter’s ongoing coverage of COVID-19’s impact on oncology. A full list of our coverage, as well as the latest meeting cancellations, is available here.

The first COVID-19 patient walked into a Mount Sinai ER on March 1.

“It was somebody who had some foreign travel under their belt, and they’d returned, and they weren’t even that sick, actually. But they showed up in the ER, because they were suspicious,” Ramon E. Parsons, director of The Tisch Cancer Institute at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, said to The Cancer Letter.

Over the three months that followed, half of Mount Sinai’s cancer doctors became COVID doctors, taking care of the sick at the hospital system’s 45 COVID centers, contributing to the standards of managing the disease.

“Right in the heart of this, we had several of our fellows deployed into the ICUs, and at the same time we were speaking with the renal staff and some of the other physicians in the other disciplines on how to manage these patients,” Parsons said. “There was this really cool thread of emails that we went through our Deputy Director William Oh, where the health system basically in one week changed the standard of care for our patients to include anticoagulation.”

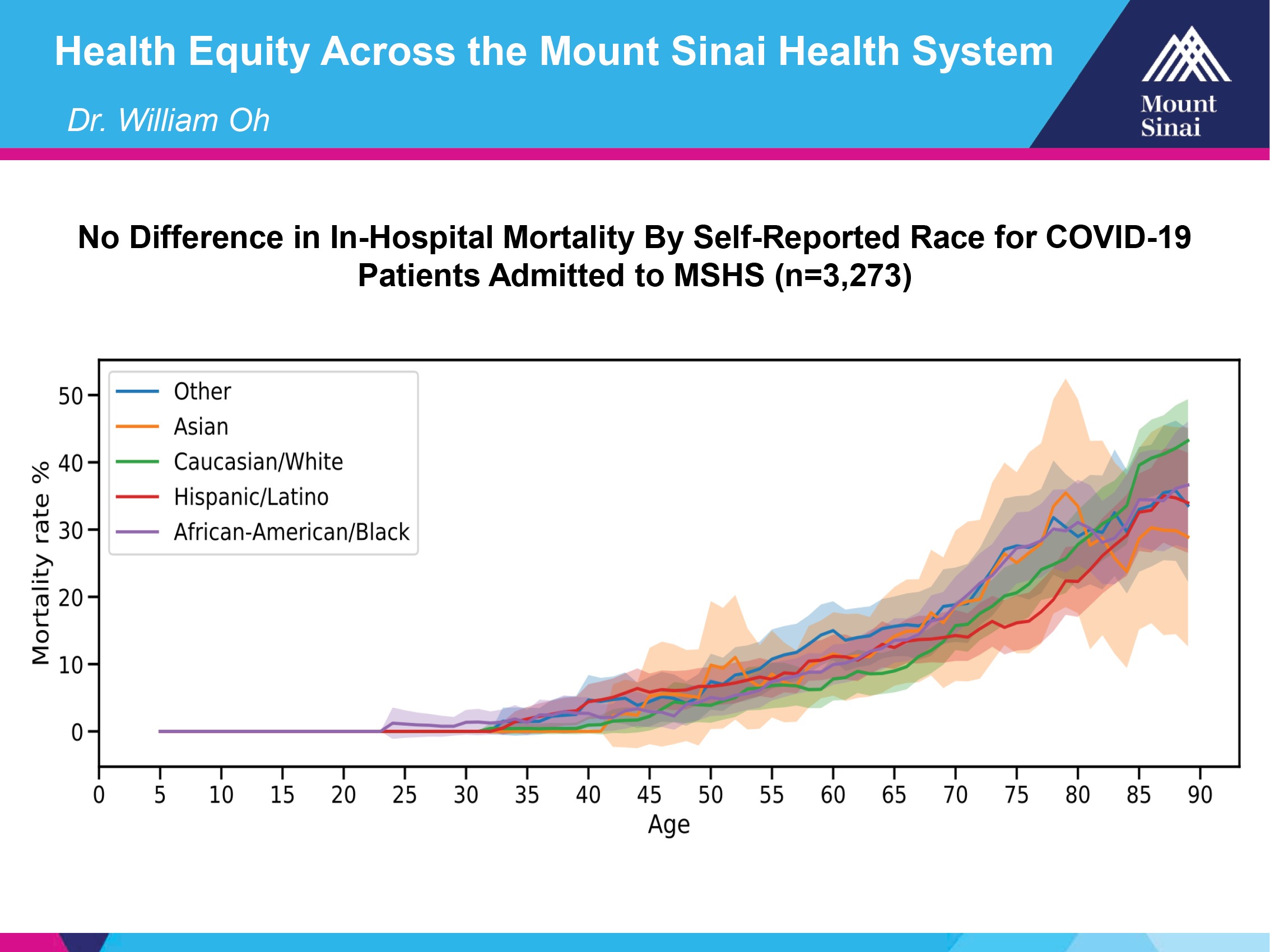

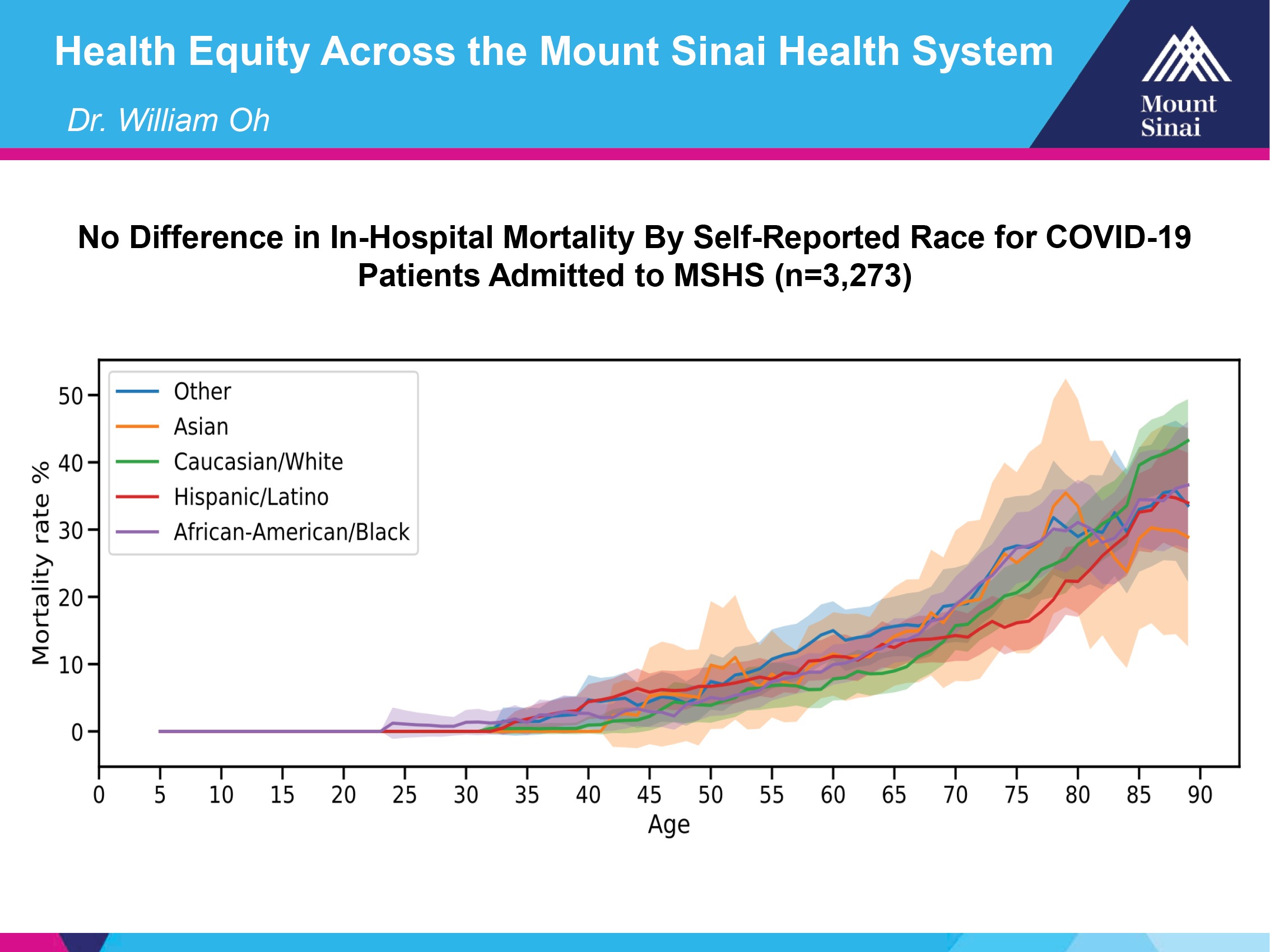

Looking at in-hospital deaths, Parsons doesn’t see much difference by race, a finding that suggests that equal treatment produces equal outcomes.

“The bottom line is, even though there are absolute differences, they’re not like what we’ve been seeing in the news about very, very markedly different outcomes,” Parsons said. “Obviously, some people could come in here sicker than others, but we have one system that applies the same standard of care to everybody.”

On the basic science side, Mount Sinai has developed a serology test and provided its components to NCI, where it was used to standardize and validate a panel of sera for use in evaluating serology devices submitted to the FDA from multiple manufacturers.

“The materials that Mount Sinai sent enabled us to get started much faster in evaluating these devices for the FDA,” NCI Principal Deputy Director Doug Lowy said to The Cancer Letter.

NCI is designing a serology research program, funded with $306 million in new funds. The money will be used “to develop, validate, improve, and implement serological testing and associated technologies” under the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act (P.L. 116-139). On May 12, the NCI Board of Scientific Advisors approved concepts for an RFA and an RFP to support research in serological testing (The Cancer Letter, May 15, 2020).

“Because we were able to set this test up and published it early on, a lot of other centers have been asking for the test from around the country,” Parsons said. “I think we’ll need to do this trial to measure the seroprotection of titres, because once we know a number or a cutoff that is generally seroprotective for people so that they can’t be reinfected, we’re hoping to see, with any luck, some herd immunity, as long as these titres are long-lasting. We don’t know that yet.”

“As you can imagine, we basically were down to roughly 40% volume at the low point. From the point of view of patient volume, we had to stop screening for cancer. So, there are very few new patients coming into our hem/onc treatment centers and of course we limited in person visits during the peak as much as possible,” Parsons said. “Recently, we’ve actually seen a spike in radiation oncology treatment, because of postponed surgeries, and we’ve opened our surgical efforts, starting a couple of weeks ago for some really pressing cases. With more last week, and even more this week.

“We’re starting to reopen, but, basically, it’s been a very tough time. All our department chairs and institute directors are taking temporary pay cuts. We’ve asked some of our staff to furlough, using a one-day-a-week furlough policy through New York State’s Shared Work Program.”

Cancer patients are returning.

“We’ve been screening them for COVID-19 symptoms by phone the day before, and then at the door when they come in. All patients receiving chemo are getting tested. It’s a safe environment, but as you can imagine, there’s some reticence, I think, after this crisis, to come into a medical center,” Parsons said. “But I think it is safer, frankly, than going to the supermarket, in my opinion, at this point.”

This conversation is part of an informal series of stories, interviews, and commentaries that track cancer institutions as they seek to reopen, reorganize, and reinvent in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic:

Programs designed to meet the NCI Community Outreach and Engagement requirements for cancer center designation have positioned the University of Miami Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center to monitor the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in South Florida (The Cancer Letter, May 22, 2020).

Three months after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance is ramping up plans for a comeback of cancer services (The Cancer Letter, May 15, 2020).

Health systems and academic cancer centers are cutting expenses to make up for operational shortfalls resulting from the pandemic—laying off employees, furloughing staff, and cutting salaries and benefits (The Cancer Letter, May 8, 2020).

Community oncology practices are experiencing a significant decrease in patient volume, as weekly visits dropped by nearly 40%, while cancellations and no-shows have nearly doubled (The Cancer Letter, May 1, 2020).

Parsons spoke with Paul Goldberg, editor and publisher of The Cancer Letter.

Paul Goldberg: What role did Mount Sinai play in managing the pandemic in New York?

Ramon Parsons: On March 1, we had our first patient here at Mount Sinai. It was somebody who had some foreign travel under their belt, and they’d returned, and they weren’t even that sick, actually. But they showed up in the ER, because they were suspicious.

We just had our site visit from NCI at the end of January, and gotten our site visit pink sheet back, which had said we had gotten a good preliminary verbal score. So, we had a retreat on March 6, where we were very excited about our effort to develop our cancer center themes and programs—and it was all good.

At that point, the news was circulating that COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 was in New York City, but it was just a few patients. What you’ll see here, in this slide, by the middle of March, new cases began to rise rapidly. Testing was not readily available yet, because we had to develop the ability to test for the virus in house. The graph includes patients at the multiple hospitals in our health system, the Mount Sinai Health System.

You can see, we had a plateau from early April to mid-April, and then it’s been sort of gradually going down. This data is now from last week. In the past week it’s come down a little bit, not much. It’s a very gradual decline, but we are seeing a lot fewer patients coming into our health system.

So, that’s the big picture.

First of all, we had to redeploy a lot of our cancer physicians to the COVID units. They were at the front line. We generated a COVID-19 cancer floor in the hospital and an outpatient infusion center for COVID-19 patients. On March 20, we shut down our research laboratories, and at the same time shut down as many clinical trials for cancer as possible.

We went from roughly 140 open trials down to 19, and the research laboratories were only allowed to have a skeleton crew to maintain mouse colonies and other stocks that needed to be maintained—and to do COVID-19 research.

The students and faculty and postdocs not directly involved in COVID-19 research were asked to work from home, and they have been productive. Here’s just a snapshot of some of the papers and activities that have been coming out from our investigators.

I focus on our clinical investigators, because these clinical investigators were serving on the front line, seeing patients with COVID, or actually going into the hospital and working hospital shifts.

For example, Elisa Port, [associate professor of surgery], a breast surgeon who’s head of our Dubin Breast Center worked in Mount Sinai Brooklyn, which was hit really hard, for a long weekend, and where she helped out in the emergency room, admitting patients and triaging them.

This is a photograph in one of our outpatient centers.

This is the Dubin Breast Center with chairs turned around to have some social distancing. The picture shows how empty it was in April, when people just didn’t want to come into the hospital.

One of the things that we’re pretty astounded by is looking at the racial breakdown in our hospital system. You can see the red line for Hispanic, Latino, the green line is for Caucasian white, and then you can see African-American is the purple line.

Basically, what you can see is these are the margins of error for all these different subtypes, based on the numbers, because you can see that they’re pretty wide out here, when you have higher ages. But the bottom line is, even though there are absolute differences, they’re not like what we’ve been seeing in the news about very, very markedly different outcomes.

Obviously, some people could come in here sicker than others, but we have one system that applies the same standard of care to everybody.

Right in the heart of this, we had several of our fellows deployed into the ICUs, and at the same time we were speaking with the renal staff and some of the other physicians in the other disciplines on how to manage these patients.

There was this really cool thread of emails that we went through our Deputy Director William Oh, where the health system basically in one week changed the standard of care for our patients to include anticoagulation.”

This is just a study that came out of that effort already showing that it does seem to provide some protection. [J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 May 5:S0735-1097(20)35218-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.001.]

Valentin Fuster, [professor of cardiology and director of the Zena and Michael Wiener Cardiovascular Institute], is leading this effort. But we—through William Oh, [chief of the Division of Hematology and Medical Oncology at the Mount Sinai Health System and deputy director of The Tisch Cancer Institute]—had a lot to do with changing this policy, and, obviously, it looks like that has been helpful in terms of the survival for patients.

This next slide is an anecdotal story, but here’s a very interesting story of one of our physicians, Thomas Marron, who, in early March, got COVID-19. He’s an assistant professor medical oncologist—one of our young stars. He’s an MD, PhD cancer immunologist, and he’s been opening up a lot of phase I trials in the cancer immunology space for the last few years.

This is just his journey. He told us about his journey, about how he got the disease early on, how he helped out with the biorepository, where now we’ve collected from over 500 patients that were acutely ill here in the hospital.

This effort was led by the co-leader of our cancer immunology program, Miriam Merad, [the Mount Sinai Endowed professor in Cancer Immunology, director of the Precision Immunology Institute at Mount Sinai School of Medicine and is the Director of the Mount Sinai Human Immune Monitoring Center], who was interested in seeing how the immune system was causing morbidity and mortality in this disease, which is apparent because many of the cytokines that are being released when patients are infected are nearly the same level you see when you have cytokine release syndrome in the setting of a variety of immunotherapies that are given to people. By the way Dr. Merad was just elected to the National Academy of Sciences.

He then volunteered on the COVID-19 unit. We had to expand to 45 COVID units here at Mount Sinai Hospital alone. Normally, of course, there are no COVID units, and so the number of units in the hospital had to expand.

Almost half of our physicians were redeployed to take care of COVID patients, with the rest needing to cover our cancer patients, of course, with a lot of telemedicine. Also, we had to help out with the clinical trial efforts. Our clinical trial office was redeployed to help out with one of the trials that we’re quite proud of, our convalescent plasma trial that we helped set up, which is looking like it is having some impact, although, we’re still having to wait to see what that is.

Only a small subset have been studied so far, which does show some benefit for patients.

We’ve been helping out with clinical trials for moderate and severe COVID-19, including immunomodulating trials. This is just some of the types of trials he’s interested in.

Basically, the first phase of infection is there’s just not enough immune response, and the virus can grow unabated.

Then, once it’s recognized, the hypothesis is that there’s too much immune response, even when the virus is already slowing down, and this causes blood clots, hypoxia, multi-organ failure and loss of macrophages, and pus in the lungs.

He’s got a trial that he’s going to be opening or has opened for using lambda interferon to affect the first phase, and then another trial using an inhibitor, an immune-modulatory inhibitor for the second phase, where the immune system is over-reactive.

We are very fortunate to have a wonderful microbiology department here at Mount Sinai. It’s led by Peter Palese,[professor and chair of the Department of Microbiology]. We also have Adolfo Garcia-Sastre, [professor in the Department of Microbiology and director of the Global Health and Emerging Pathogens Institute]. They’re both members of the National Academy of Sciences, experts on viral infections, particular influenza, but they’ve been studying the SARS viruses.

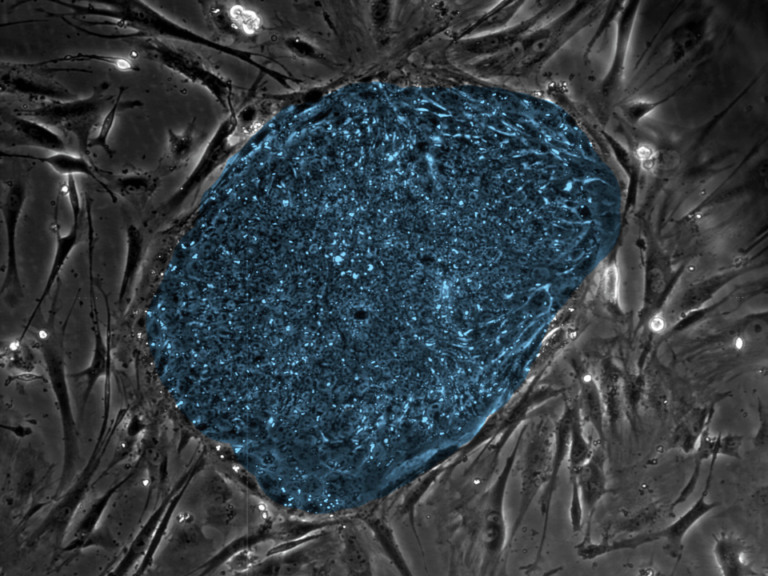

Then, finally, Florian Krammer, [professor of vaccinology at the Department of Microbiology and the principal investigator of the Sinai-Emory Multi-Institutional Collaborative Influenza Vaccine Innovation Center], who developed, fortunately, a two-step ELISA test, which turns out to be apparently the most sensitive and specific test that’s available right now, and becoming available nationally. [Nat Med. 2020 May 12. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0913-5.]

One of the exciting things that we’ve been contributing is our chair of pathology, Carlos Cordon-Cardo, [the Irene Heinz Given and John LaPorte Given Professor and chairman for the Mount Sinai Health System Department of Pathology], a cancer scientist for many years, and a long-time colleague and collaborator of mine, going way back, started to take this test and put it in the clinic so that we could measure titres for the antibodies, IgG and IgM antibodies that result from an infection that has mounted some immune response.

Now, they also have an assay for measuring antibodies’ ability to block infection in a microscale infection test, where they can see if the antibodies have the ability to block cellular infection.

Because we were able to set this test up and published it early on, a lot of other centers have been asking for the test from around the country.

He sent our blood samples as examples of positives, known positives, and negatives from prior to the infection. Carlos Cordon-Cardo organized this and sent them to the NCI Frederick, which is coordinating an effort to identify which tests are the best in this area.

The impression I’ve gotten on calls with the NCI director, who is very excited about this, basically they want us to be part of a national effort, working with NIAID, to test in a prospective clinical trial using our test at multiple centers throughout the country, to determine at what level response correlates with seroprotection from infection.

Because this will be a very important study that will allow us to get back to work in safe way—and this could potentially also be used for vaccines—to know what amount of antibody titre to the virus is sufficient to lead to protective immunity.

So, that’s very, very important. That’s something that Florian is now championing, and is getting federal funding for in the process of expanding it. I think he’s already opened the trial here, locally.

We also have been in conversation with NCI, who’s been trying to work with us to get the test into the federal government agencies that are going to be able to help propel this at a national level, so that this test, which appears to be very specific and very sensitive, can be disseminated through a commercialization effort. That’s really a very exciting thing that we’re hoping to make this widely available through that effort. It’s happening as we speak with efforts to start a new company that would be able to really ramp this up and scale it to a level that we’ve been doing really at a mom and pop level here at Mount Sinai.

In fact, cancer center labs including my own lab, one of my technicians, has been helping out with making the protein that coats the surface of the virus. It’s called the spike protein that coats the virus that’s involved in the infection process. The full-length protein is very hard to make.

So, we’ve been helping out with making it, and that’s used in the second step of the ELISA test.

Just to explain the ELISA test. Importantly, it’s a two-step test, and the first step screens and is going to have some false positives.

So, if you get a positive on the first round, you then have the second round of testing, which is the full length. The first one uses the RBD, receptor binding domain, of the spike protein. And then the second one is the full-length spike protein, and you need to be positive for both tests to be considered a positive in this assay. Then, obviously, there’s a titre possibly associated with the strength of the immunity, which we still don’t understand exactly, if it does protect against viral infection. And that’s, as I mentioned earlier, an ongoing effort.

At the same time, NCI has just started a new [serology] program [(The Cancer Letter, May 15, 2020)]. There’s going to be an RFA for it.

Basically, in that effort, they’ve been reaching out to us, and they want us to put together a team of investigators to compete for U54 and also for U01s, but also to expand are CLIA lab infrastructure, so that we can scale beyond what we currently have for serology testing on campus. So, we’re in the midst of putting that together.

How did the pandemic affect the cancer center financially?

RP: Well, it’s been a pretty big hit. As you can imagine, we basically were down to roughly 40% volume at the low point. So, from the point of view of patient volume, we had to stop screening for cancer. And, there were very few patients coming into our hem/onc treatment centers.

We’ve recently seen a spike in radiation oncology treatment, because of postponed surgeries, and we’ve opened our surgical efforts, starting a couple of weeks ago for some really pressing cases. With more last week, and even more this week.

We’re starting to reopen, but, basically, it’s been a very tough time. All our department chairs and institute directors are taking temporary pay cuts. We’ve asked some of our staff to furlough, using a one-day-a-week furlough policy through New York State’s Shared Work Program. But we’re starting to see increased volume in the clinics now, and we’ve created, I believe, a very safe place for our patients. Our physicians here on campus have almost half the rate of infection that is seen in the general population here in New York City. So, our PPE is working, and we’ve created, as I mentioned earlier, spaces where our COVID patients are seen separately from our non-infected patients to protect the non-infected patients.

To answer your question, yes, it’s been a big financial hit. We’re very worried about it, frankly, going forward, because, as you know, revenue is lagging from billing. So, that part of the wave has not really hit our shores yet, but the institution is doing everything it can right now to weather the storm.

I guess you were taking care of the COVID patients. That was billing too; no?

RP: Yeah, the difference, though, is COVID remuneration is not the same level as you would get from surgery, and some of the infusion that we’re getting. It’s really a matter of, frankly, our cash flow changed.

If you think about it, it’s just a matter of how insurance companies compensate physicians generally. They’re compensated for elective surgeries more than inpatient care. It is what it is, even though we’ve been very busy in the hospital.

That said, remember our outpatient revenue is much more important for our bottom line than inpatient revenue.

Are cancer patients returning?

RP: Yes, they are.

Actually, during this period I’ve been rounding in the hospital, in the clinics, and the outpatient clinics have been open the whole time and there are patients coming in. We also have telemedicine visits, but, of course, patients that are getting chemo need to come in.

We’ve been screening them for COVID-19 by phone the day before, and then at the door when they come in. All patients receiving chemo are getting tested. It’s a safe environment, but as you can imagine, there’s some reticence, I think, after this crisis, to come into a medical center.

But I think it is safer, frankly, than going to the supermarket, in my opinion, at this point.

What’s been the impact on basic science?

RP: We had to, obviously, shut down the labs for cancer research since the end of March. So, it’s going to be almost two months.

We just opened up this week. Research now can open up with social distancing, but the labs are only at 25% of normal capacity, to make sure that happens. I think, fortunately, we did not cull our mouse colonies, like some institutions have and, also fortunately, I think a lot of our students, because of our housing, live nearby.

So, they walk to work and don’t have to get public transportation.

It’s not great for everybody, but now I think we’re going to get back to work in our cancer research, and I think a lot of people have taken this time to write grants and papers. We’ve seen a lot of grants being submitted. I’ve checked: to a scientist, with maybe just a few exceptions, scientists have something planned for submission, either with the federal government or through a foundation in the coming cycle.

Is there a connection between COVID-19 research and cancer research?

RP: There is. Many viruses have given us important clues about how the immune system works, and here, I believe that the information we’re going to understand about how the virus can act as a Trojan horse and shut down the local immune response probably is going to give us lessons that we’re going to learn from on how cancers are able to change the microenvironment for the same purpose.

If we could talk a little more about serology testing. I understand from people at NCI that Mount Sinai played a key role in this, basically as a partner of NCI. You mentioned some of that. Is there anything else to say? Anything you haven’t mentioned?

RP: I am so proud to have such smart, resourceful and resilient colleagues, who have adapted to the crisis to take care of both cancer and COVID-19 patients.

I would say it was really dramatic. They asked us for blood products on March 27. Urgently, when this was happening.

We promised to deliver it a week later, and they hadn’t received them yet. They were just really nervous about where they were, and I was worried when we were going to deliver. The place was chaotic, because all these patients were dying, and it was really crazy here. It was the right thing to do, but at the same time, a lot of people were under a lot of stress here.

But Carlos Cordon-Cardo was able to get the samples. A federal courier from Frederick came and picked them up on April 6, and then drove right back to Frederick, MD, to drop them off. They had started testing them literally, I think, as soon as he got back to Frederick.

So, it was really very dramatic that we were able to get them that, and then we had follow-up calls with the NCI director. One on a Saturday, in fact.

First, during the week to tell us that they really had great results and that they wanted to scale this test nationally. Then, with HHS, to try to figure out how do we get into the health system to actually operationalize that.

That’s been super exciting for us, and we’re very proud of that effort, and I’m very proud of the people who’ve worked on that here. I mentioned everybody’s name already who was involved in that.

The other thing that you might be aware of is that we’ve had at Mount Sinai a biobank collected from our patients. It’s called BioMe, which is basically a serum sample that’s collected and some DNA that’s collected on a volunteer basis with informed consent for basically mostly healthy patients, but also patients that somehow interact with our health system at various levels, including several thousand cancer patients.

Those were collected pre COVID-19, and also, we collected into March of 2020, when we shut down the project. So, they’re very interested in studying those samples, because many of those people now have gone on to get infected, and to figure out when did COVID-19 really first hit our shores, because we’ll have a canary in the coal mine with those patients. And also, to see if we can identify various either genetic risk factors, and that’s something that Steven Chanock, [director of the NCI Division of Epidemiology and Genetics] is very interested in following up with.

I’d like to mention the people we’ve worked with at NCI. In addition to Ned Sharpless. Doug Lowy, the NCI deputy director, was very much involved in these conversations and so was Jim Cherry [scientific program director, Office of Scientific Operations, NCI at Frederick], and Ligia Pinto, [director of the Vaccine, Immunity and Cancer Program at the Frederick National Laboratory], who is involved in standardization of serologic testing at NCI Frederick. We’ve had a lot of conversations with them that have been very helpful and also with Steven Chanock.

So, it’s been an exciting time. We feel like we’re really helping out. One thing I would like to end with is our cancer center just went through the renewal process. The site visit was in, as I mentioned, Jan. 30. We should be getting our final summary statement anytime now in May, and our score is such that we’re going to get renewed.

So, our plan is really a multipronged plan to expand our efforts to understand the tumor microenvironment and its role in cancer progression and also treatment.

We’re also very interested in understanding the disparities that are occurring in our city—our catchment area is New York City—and trying to figure out what they are and ways we can address them.

Then a third area that we’re very excited about is, because in the past this cancer center was focused only on East Harlem, Central Harlem, and the Upper East Side as its catchment, now that we’ve expanded to all of New York City, we wanted to expand our clinical trial network across our health system.

One thing that we’ve really done here is our CTO, working particularly with Karyn Goodman, [professor of radiation oncology and associate director for clinical research], was really lifted a lot, and our CTO helped out, the convalescent plasma clinical trial tremendously that the ID department led.

We’ve helped consent patients throughout the health system for that trial, and so we feel like we’ve learned from that experience, and now, we’re going to be able to open up trials; obviously, not every trial, but trials that would be amenable to multi sites, perhaps oral medications for instance, we’re going to be trying to open up throughout the health system. So, that’s a very exciting development that is a consequence of our experience with COVID.

Looking at the recent FDA guidance about the serology tests, your test, of course, is mentioned as one of the great tests to use. Obviously, it couldn’t have possibly existed before the spread of the disease. Did it just sort of happen very, very quickly that you developed it?

RP: The virus sequence was published sometime in early February, from China.

Basically, just based on they are very adept cloners, I believe that they simply just cloned the sequence based on the DNA sequence.

As I was saying, this microbiology department is really interested in influenza, and as you know, influenza has been one of these intractable diseases that we still don’t have an effective vaccine for. The vaccine has to be changed every year, and it’s never very good, to be honest. So, they’re fascinated with this problem, and similarly they’re fascinated with other viruses that can cause similar morbidity and mortality.

So, they were, I’d say, intellectually primed to be very interested in working on this,

As you know, COVID-19 affects cancer patients just as much as anybody else, and we are very concerned about that, as is everybody who works with cancer. But we’ve put together a COVID-19 registry at the institution, and there’s a cancer subcommittee that includes the associate director for population science and other cancer center members that’s part of that committee.

And, as I mentioned, there’s a biorepository for COVID-19 that’s led by the co-leaders of our cancer immunology program, Miriam Merad.

So, we are in a position to follow the trajectory of the health of our patients and understand better who’s going to be at risk. We have some clues from China, but we’re going to really understand, I think, from our experience, and also pooling our data with other centers, who is really the most at risk for this disease.

At this point, there’s a lot of anecdotal information, but codifying that is going to be very helpful.

Do you think better and more widespread use of serology testing would help to get doctors and nurses back to work and patients back to the clinic?

RP: I do think so. I think we’ll need to do this trial to measure the seroprotection of titres, because once we know a number or a cutoff that is generally seroprotective for people so that they can’t be reinfected, it’s almost like we’re going to see, with any luck, some herd immunity, as long as these titres are long-lasting. We don’t know that yet.

So, yes, I think this is going to be very helpful. It’s also going to help our economy get back to work, too, and reduce the spread, be able to trace contacts much better.

How soon will you get the data do you think?

RP: That’s a really, really good question, and I don’t know the answer to that. Again, that’s something that Florian Krammer would be able to tell you. I just spoke to him about maybe a week ago, where we heard it most recent. Still not enough information to know for sure about seroprotection yet in a large study.

Thank you very much.