This story is part of The Cancer Letter’s ongoing coverage of COVID-19’s impact on oncology. A full list of our coverage is available here.

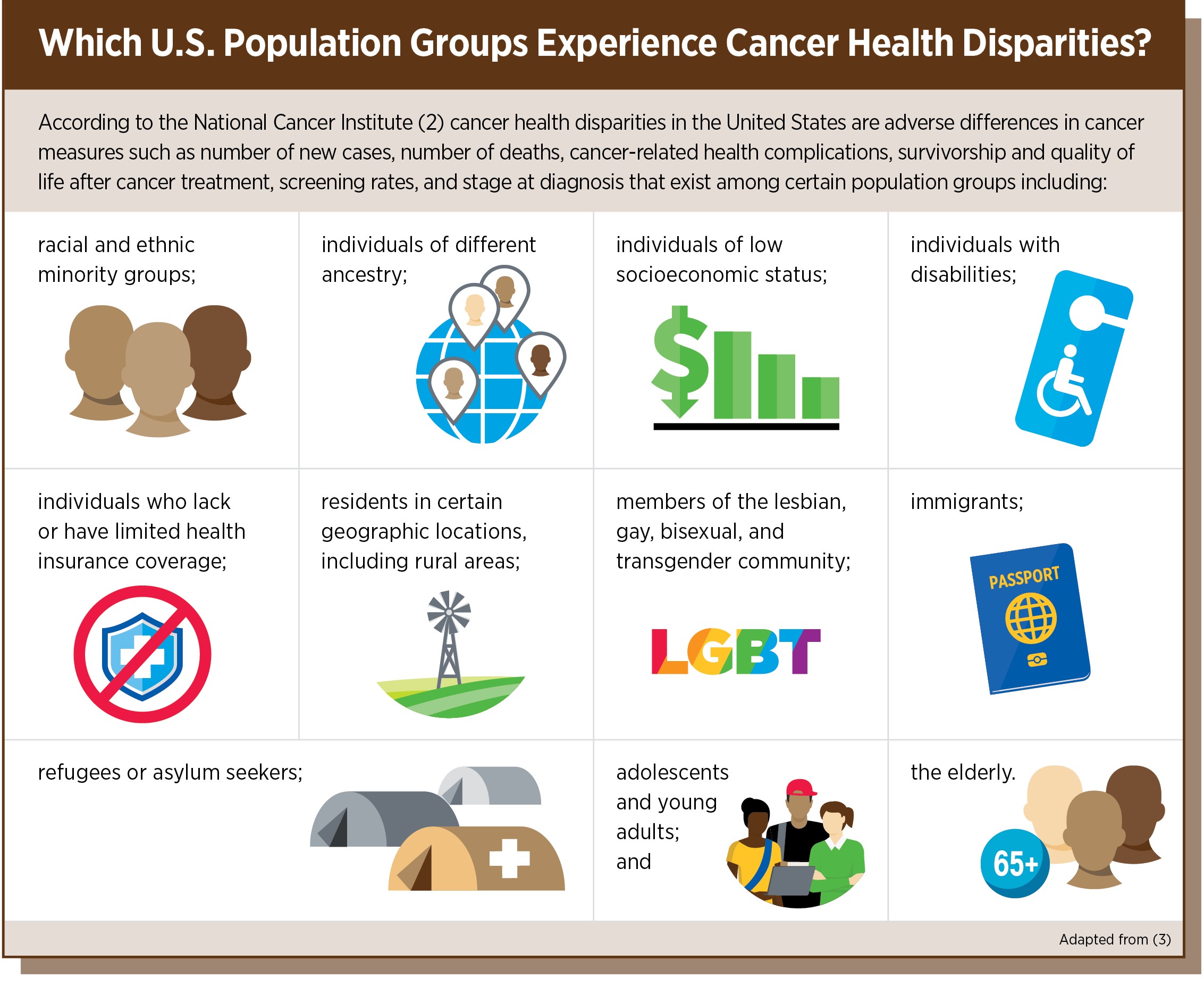

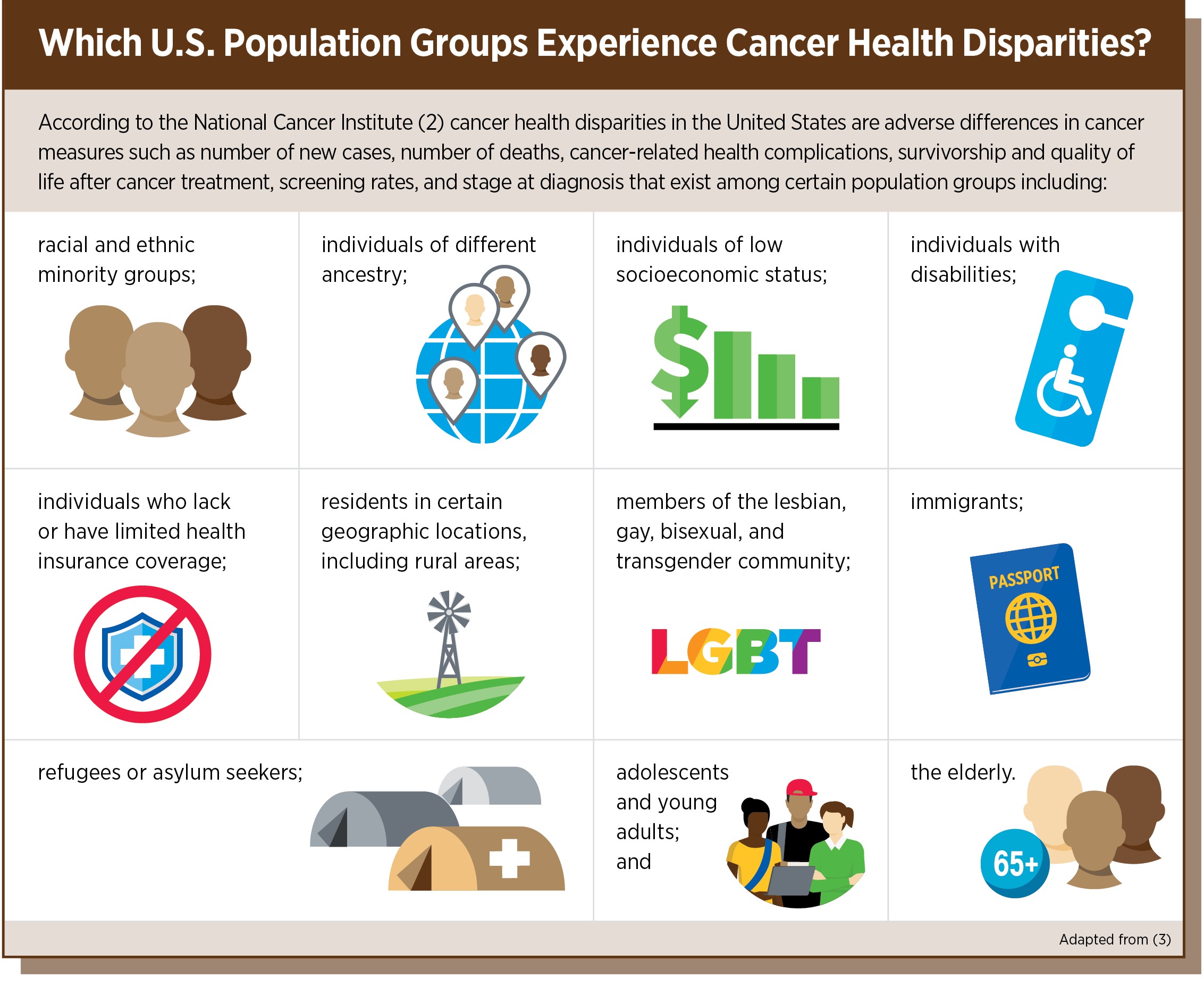

The American Association of Cancer Research Sept. 16 published a comprehensive report on disparities in cancer, describing in deep detail the outsized toll that cancer exacts on racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations.

The document, AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2020: Achieving the Bold Vision of Health Equity for Racial and Ethnic Minorities and Other Underserved Populations, is the first of its kind from the professional society. AACR’s virtual congressional briefing is available here.

“We tried our best to spell out some of those things that we hope that our leaders and individuals in leadership positions and in positions of influence can see and read,” John D. Carpten, chair of both the AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2020 Steering Committee and the AACR Minorities in Cancer Research Council, said to The Cancer Letter. “I think there’s a lot to unpack.

“We’re living in an incredible time right now. I’m not saying incredible in a good way; I’m saying, in an incredible time, where social aspects related to social injustices have, arguably, an all-time-high spotlight, where the COVID-19 pandemic has brought into full view disparities in health care,” said Carpten, professor and chair of translational genomics, and director of the Institute for Translational Genomics at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine.

The AACR report states that:

African Americans have had the highest overall cancer death rate of any racial or ethnic group in the United States for more than four decades.

Hispanics have the lowest colorectal cancer screening rate of any racial or ethnic group in the United States.

American Indians/Alaska Natives have the lowest breast cancer screening rate of any racial or ethnic group in the United States.

Complex and interrelated factors contribute to cancer health disparities in the United States. Adverse differences in many, if not all, of these factors are directly influenced by structural and systemic racism.

Racial and ethnic minorities are severely underrepresented in clinical trials, and understanding of how cancer develops in racial and ethnic minorities is significantly lacking.

Many of the U.S. population groups that experience cancer health disparities, in particular, racial and ethnic minorities, are also experiencing disparities related to coronavirus disease 2019. Many of the factors driving COVID-19 disparities overlap with the factors that contribute to cancer health disparities.

Experts predict that the COVID-19 pandemic will exacerbate existing cancer health disparities as a result of the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations.

The report notes the following areas of progress in the reduction of cancer health disparities:

Differences in the overall cancer death rate among racial and ethnic groups are less pronounced now than they have ever been. In 1990, the overall cancer death rate for African Americans was 33 percent higher than the overall cancer death rate for whites. By 2016, it was 14 percent higher.

Recent studies have shown that racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes for some types of cancer could be eliminated if all patients have equal access to standard treatment.

Tailored outreach and patient navigation can help reduce disparities across the spectrum of cancer care.

Several studies and initiatives designed to address gaps in our knowledge about cancer biology in diverse populations are underway, including AACR Project Genomics Evidence Neoplasia Information Exchange (GENIE) and the National Cancer Institute-funded African American Breast Cancer Epidemiology and Risk (AMBER) Consortium.

Over the past two decades, diversity-focused training and career development programs have enhanced racial and ethnic diversity in cancer training.

“I think some of the other important aspects are related to socioeconomic issues, how the financial impact of not addressing disparities—I think we presented some data where a study is done looking at healthcare costs between 2003 and 2006—was at the level of a trillion dollars,” Carpten said. “So, that can’t be ignored.”

In an effort to eradicate the social injustices that are barriers to health equity, the report concludes with a call to action to policymakers and all stakeholders to:

Provide robust, sustained, and predictable funding increases for the federal agencies and programs that are tasked with reducing cancer health disparities.

Implement steps to ensure that clinical trials include a diverse population of participants.

Support programs to make sure that the healthcare workforce reflects and appreciates the diverse communities it serves.

Prioritize cancer control initiatives.

Work with members of the Congressional Tri-Caucus—comprising the Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus, Congressional Black Caucus, and Congressional Hispanic Caucus—to pass the provisions included in the Health Equity and Accountability Act.

“What we hope is that, along with this progress report and all of these other societal issues that we’re facing and dealing with, that we can expose these things and begin to identify solutions together,” Carpten said. “And to see real resources, hard dollars be brought to bear on solving these problems and addressing these issues.”

Carpten spoke with Matthew Ong, associate editor of The Cancer Letter.

Matthew Ong: Thanks for your work on this incredibly important report. What’s unique about the AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report, and what are your takeaways?

John Carpten: It gives us, I think, the opportunity to really provide the public with a baseline of where we are in our understanding of cancer disparities. Where are we? What progress have we made? What gaps remain? And then, as a field, where do we think action could be taken, what action could be taken to allow us to be more efficient and more effective in addressing and ultimately eliminating cancer disparities?

So, to have the opportunity to present this in an open form with public input and questions and comments that included access to our legislators is just unbelievable and such an incredible opportunity for AACR and the field of cancer health disparities to really capture their interest, to really let them know how serious of an issue this is. It’s also an update on the research that’s ongoing and the steps that we need to take. From my perspective, that’s what we had hoped to do, and I think we were able to accomplish today.

In terms of takeaways, I think, undoubtedly, including the patient advocates and their stories as part of the briefing, as well as part of the panel, and then finally, to have them provide their stories in detail in video format, To me, that was the heart and the foundation of the entire day, as I looked at the questions in the comments that were coming through, and even all of the emails and text messages that I’ve received since the briefing closed.

So, many people spoke to how incredible the patient advocates were, and how it personalizes the issue in such a way that I think will help us gain the type of support that we need to help us address these issues. And, of course, having the videos from our legislators was also incredible. It was also obvious that a number of the questions had a common theme.

I think some of the questions around being careful as we consider the study of cancer health disparities, because it is multifactorial and how we have to take into account both the standpoint of the social aspects that drive cancer disparities, as well as genetic ancestry, which is brought to bear on the biological side of cancer health disparities.

But, importantly, as was mentioned by our panel members, is that those two things do go hand-in-hand and could possibly have an impact on each other. And that’s one of the areas that the field needs to move towards, which is these very comprehensive, interdisciplinary, or multidisciplinary study designs.

What are some of the cornerstone data points from the survey that you’d like to highlight?

JC: That’s a great question.

I think one would be the lack of diversity in clinical trials. I think that is an area that’s central to an agenda for cancer health disparities research going forward—how do we work towards increasing diversity in clinical trials?

The report provides some really important information, when we consider the impact that certain cancer disparities exact on various communities and populations and the lack of appropriate representation in clinical trials and biomedical research cohort studies.

And how, without having those data on the value of increasing diversity, we’re losing an opportunity to gain a broader understanding of the efficacy and impact of these various therapies for all people.

I think some of the other important aspects are related to socioeconomic issues, how the financial impact of not addressing disparities—I think we presented some data where a study is done looking at healthcare costs between 2003 and 2006—was at the level of a trillion dollars. So that can’t be ignored.

I think one of the other really important aspects of the report has to do with the limited diversity in the workforce, particularly as we consider biomedical and STEM careers, such as cancer research and how we don’t seem to have adequate representation.

And there doesn’t seem to be a relationship between diversity in the workforce and this important area of research, which is cancer disparity. So, there seems to be a lack of representation, and to some degree, a lack of appreciation of what that really means.

And so, the report includes quite a bit of information on the numbers, the lack of diversity when we look at a general population representation, versus representation in the workforce. And it talks about some of the programs that are in place to help work towards mitigating that, but also the fact that we need to do better.

Finally, the call to action drives home the points that we think are really important—that we would like to work with Congress to ensure that there’s growth in biomedical research funding, specifically in cancer health disparities, that we are working towards governmental initiatives to help us drive more diversity in clinical trials, and again, to advance and increase diversity in the workforce.

We need to ensure that legislation is put in place to ensure that cancer disparities have a significant place in the development of new policies. And so, the call to action is really the critical part of this document.

It’s noteworthy that the gap in the overall cancer mortality rate between Blacks and whites has more than halved since the ’90s, while the proportion of racial and ethnic minority patients in NCI-funded clinical trials has nearly doubled over about the same period (The Cancer Letter, June 26, 2020). What do these trends point to, and what’s been working?

JC: I think I mentioned early in my keynote that we’ve made progress. We’ve seen a 26% reduction in cancer mortality rates since the declaration of the war on cancer.

But I think, even when you look at those particular numbers that you just mentioned, there’s also evidence that gets presented at ASCO, we have large phase III definitive clinical trials for prostate cancer, which is among the most significant disparities, and there’s 3% minority representation in those clinical trials.

So, I think there’s one way to look at things where they’re broader, especially when it comes to clinical trials that are related to chemotherapy. But we think about some of the more innovative drug development programs.

When we think about targeted therapies, we think about immunotherapeutics. I don’t think the numbers are as they seem. I think those numbers could be dug into a little bit deeper, and we’ll see that this is definitely a significant issue and challenge that we need to overcome.

Also, we’ve heard a lot from NCI about excess cancer deaths from COVID-19, but how will the pandemic change our outlook on cancer mortality, where disparities are concerned and in terms of where the burden of cancer is going to fall over the next decade? In that context, what have you learned about the disparate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color?

JC: I think the jury is still out. We’re still early. I think, undoubtedly, we know that there’s clear evidence that there are disparities in SARS-CoV-2, incidence rates and death rates among many underrepresented minorities and the medically underserved, which we consider people who don’t have private insurance.

We also know that many of the safety net hospitals that reside and serve many of these underserved communities are under-resourced.

Of course, those are the facilities where many of these individuals receive their cancer care, and these health systems are considerably overburdened by COVID-19. And so, what’s happening is that many services, elective services like screening, have been put on hold, or delayed. And many elective procedures that could be surgeries for early stage cancers are being delayed, and in some cases canceled, because of the overburdening of the health system due to COVID-19.

So, undoubtedly, we will see a significant impact in cancer overall in the coming years, because of these issues.

But more than likely, we can almost guarantee that there’ll be a heavier burden on the underrepresented and underserved communities, because of the fact that they are already dealing with a situation where their care is coming from under-resourced healthcare facilities.

We are more than likely going to see an exacerbation of these disparities in the coming years because of the pandemic.

How does the survey illustrate the importance of diversity in leadership and in a workforce in oncology? And specifically, how have these diversity-focused training and career development programs over the past two decades made a difference on the overall cancer mortality for communities of color?

JC: That’s a great question. In terms of something having impact and making a difference,

I can only speculate that yes, some of the growth that we’ve seen and advances towards diversifying the workforce have likely had some impact on some of the improvements we’ve seen in outcomes, but it’s modest at best. Because, when you look at the numbers, they’re still critically low.

Has there been progress? Absolutely. I wouldn’t be sitting here on the phone with you if there had not been progress, but we still can’t ignore the fact that the pipeline is still a bit limited, even for those students that get through K through 12 into undergraduate.

Are they able to be competitive for internships and research positions, such that if they do decide to move on into a higher education, whether it be medical school or otherwise, do they have the credentials that are needed to be competitive?

I have to give a lot of kudos to our historically black colleges, particularly those that have medical schools, for their work in supporting the development of careers for doctors and health professionals of color.

And I think that you’re right, I do believe that whether or not we’re there now, or whether we get there in the future, that by diversifying the workforce, we will have a better chance of impacting, for instance, diversity in clinical trials.

Perhaps a diversification of the workforce will help us in our efforts to increase diversity in clinical trials.

Because, we know that there are trust issues involved in some of the limitations of certain individuals wanting to participate in clinical trials. So, at the end of the day, there is a relationship between those two things.

What we hope to do through the AACR and other partnering organizations is to work hard towards developing new programs that offer equitable opportunities to minorities, for access to funding, to grants, to fellowships, access to internships, as well as trying to work towards ways to better mentor and develop the careers of minority scientists towards successful careers in biomedical research and health professions such as oncology.

What is your message to leaders at healthcare institutions—federal agencies, academia, industry, advocacy—who are reading this? What can we learn from the past?

JC: I think one important part is the call to action.

We tried our best to spell out some of those things that we hope that our leaders and individuals in leadership positions and in positions of influence can see and read.

I think there’s a lot to unpack. We’re living in an incredible time right now. I’m not saying incredible in a good way; I’m saying, in an incredible time, where social aspects related to social injustices have, arguably, an all-time-high spotlight, where the COVID-19 pandemic has brought into full view disparities in health care.

And so, there’s a convergence of all of these things happening right now. What we hope is that, along with this progress report and all of these other societal issues that we’re facing and dealing with, that we can expose these things and begin to identify solutions together.

And to see real resources, hard dollars be brought to bear on solving these problems and addressing these issues.

So, access to resources, bringing everyone to the table so that everyone has a voice is another important thing that people of influence can do.

By diversifying these conversations, perhaps we can come up with more creative and innovative approaches to solving these problems.

Did we miss anything?

JC: We’re really excited and honored to have the opportunity to share with the world the progress and a vision for addressing understanding and ultimately eliminating cancer disparities.

This is a historic first-of-its-kind document, and it will provide our legislators with some of the information and evidence that they need to help guide them on this really important issue, and to ensure that resources are brought to bear towards helping us solve this issue.