This story is part of The Cancer Letter’s ongoing coverage of COVID-19’s impact on oncology. A full list of our coverage, as well as the latest meeting cancellations, is available here.

The predicament in which Janice Cowden finds herself is so ordinary in today’s pandemic-struck America that it’s repeated thousands of times—and therein lies its horror.

For nearly two weeks, Cowden, a 62-year-old survivor of metastatic breast cancer, has had a severe cough, fever, body aches, wheezing, and labored breathing—all symptoms of COVID-19.

As a patient with cancer over the age of 60, she is one of many with underlying illnesses who are most vulnerable to the disease.

At this writing, after two doctor’s appointments and a trip to the ER, Cowden, a resident of Bradenton, a town in central Florida, hasn’t been tested for coronavirus. She is one of thousands of people in the U.S.—with or without cancer—who are having to jump through hoops to receive testing, often with no success.

Preliminary analysis from fatality data in Italy show that cancer patients may account for 20% of all COVID-19 deaths in a small study by the Italian National Institute of Health.

A conversation with Giuseppe Curigliano, clinical director in the Division of Early Drug Development for Innovative Therapy, co-chair of the Cancer Experimental Therapeutics Program, Department of Oncology and Hemato-Oncology, University of Milan, European Institute of Oncology, appears here.

A review of early data and projections related to the COVID-19 pandemic appears here.

Persistent symptoms aren’t even the worst of it for Cowden.

On Feb. 29, in the early days of the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States—before meetings and conferences in oncology were canceled en masse—Cowden and more than 300 people gathered for The Southwest Florida Metsquerade fundraiser.

Cowden, who has triple-negative stage IV disease, was one of 50 or-so survivors at the Metsquerade. There, she posed for photos, gave hugs to friends she hadn’t seen in months, laughed and cried with fellow advocates. These were, after all, people she may or may not ever see again.

A week later, Cowden had the symptoms.

“If I were to have the disease—I would hope that no one else in that group in particular, those of my friends who have metastatic breast cancer, get sick,” Cowden said to The Cancer Letter. “I think we’ve probably reached that point where they would maybe have it by now. I don’t know. It’s just disappointing to me that I can’t at least have it ruled out.”

Fran Visco, president of the National Breast Cancer Coalition, said the government response and subsequent testing for COVID-19 in the U.S. is horrifying.

“Here, you have an individual who is trying to do the right thing, trying to get tested—because she has symptoms and she was in the presence of hundreds of other people, many of whom were probably immuno-compromised and in difficult health situations,” Visco said to The Cancer Letter. “It’s just horrifying that we don’t have a system in place that would facilitate her being tested—or anyone like her being tested—or any of us being tested.”

A cough and a fever

On March 8, Cowden developed a sore throat, a headache, and generally felt bad.

The next day, her cough worsened, and she measured a fever of 100.5. On March 10, she was wheezing, had body aches, a headache, and labored breathing.

“I do have some damage in my right lung from radiation. So, sometimes, I will tend to develop the more significant respiratory symptoms if I get an upper respiratory infection,” Cowden said.

Cowden made an appointment with her primary care physician at Intercoastal Medical Group in Florida on March 10. By then, her fever was up to 101.3, as measured in the office. The doctor ran an influenza test, which was negative. The rapid strep test the doctor administered next was inconclusive: the physician’s assistant read it as negative, the physician as faintly positive.

An X-ray ruled out pneumonia.

“Have you traveled internationally within the past 90 days? Do you know anyone who’s been exposed to coronavirus?” they asked Cowden. She answered truthfully: “No.” Apparently, this answer rendered Cowden ineligible to receive a test for COVID-19.

Cowden was sent home with a pack of steroids and a prescription for antitussive cough medicine in hand.

Intercoastal didn’t immediately return a request for comment from The Cancer Letter.

Cowden couldn’t stop thinking back to the more than 300 women who attended the SWFL Metsquerade. Receiving a negative test would enable her to say: “Even though I’m sick—no—I don’t have coronavirus. You were not exposed to me.”

“I just thought it was odd, that having been at that event, that they wouldn’t want to at least rule it out,” Cowden said.

Christine Hodgdon, one of Cowden’s friends with metastatic breast cancer and a fellow advocate, also attended the SWFL Metsquerade.

At the Metsquerade, “we were all together—hugging and taking pictures, all these things. If she does have it, it would really be nice for us to get a heads-up to know that we may have been exposed to it,” Hodgdon, founder of the Storm Riders Network—an informational resource for MBC patients, said to The Cancer Letter. “She’s a classic case. She’s over 60, she has metastatic breast cancer, and she has all these symptoms.”

On Friday, March 13, Cowden’s symptoms got worse. She could hardly breathe.

“The only improvement was with my temperature—it was no longer over 101. It was staying between 99 and 101,” Cowden said.

So, she went to her primary care provider, again, the next day.

“The primary care doctor listened and commented on how awful my lungs sounded. He did a nebulizer treatment, which did not clear the wheezing, and he determined that I needed to go to the emergency room,” Cowden said.

“And, in his words, he said ‘I want you to go to the emergency room and get tested for the coronavirus, and you’re probably going to be admitted.’”

Finally, Cowden would get the answer.

Emergency room

Cowden was seen almost immediately after arriving at the emergency room of Doctors Hospital of Sarasota.

She received several tests: A chest X-ray, labs, blood cultures, a urine culture. Everything came back OK, Cowden said.

“Once again, I explained to the physician that the primary care doctor I saw that morning had stated that I should be tested for coronavirus. And he went through the same questions and said the same thing,” Cowden said.

And yet, she didn’t receive a test—despite her worsening symptoms.

“Have you traveled internationally within the past 90 days? Do you know anyone who’s been exposed to coronavirus?”

“No,” Cowden answered once again.

Would it have made a difference had her answer been “Yes”?

It’s just horrifying that we don’t have a system in place that would facilitate her being tested—or anyone like her being tested—or any of us being tested.

Fran Visco

The hospital had no test kits to begin with, the ER doc told her.

“Honestly, I just think it would be a wise thing to do—to rule it out, because of the exposure that I had six days prior to becoming symptomatic,” Cowden said. “So many of those are friends who have metastatic breast cancer, who are extremely high risk.”

What about Cowden’s husband? Her community?

The prediction of her primary care physician was incorrect, too. She wasn’t admitted. She left empty-handed, with only a change in antibiotics to show for the visit.

“Doctors Hospital of Sarasota orders COVID-19 tests for admitted patients based on the Florida Department of Health testing guidelines,” a spokeswoman said to The Cancer Letter. “We have treated one positive COVID-19 patient. That patient has been discharged.”

Hospitals in the area only test patients who are admitted, and Cowden was not. Her symptoms weren’t severe enough. Had she developed pneumonia, or had she falsely claimed to have travelled outside the country in the past 90 days—perhaps she could have qualified for a test.

COVID-19 kits include nasopharyngeal swabs, which testing facilities like Labcorp require to diagnose whether a patient is positive.

The aftermath

Undeterred by three unsuccessful attempts to get tested, Cowden contacted her oncologist at MD Anderson Cancer Center to see whether she could intervene.

The answer was one she was already familiar with. MD Anderson, being a few states away, couldn’t help. Her oncologist recommended that Cowden reach out to her primary care provider once again.

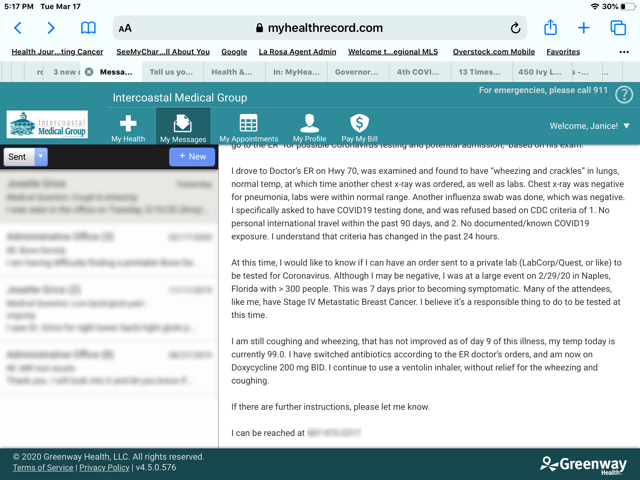

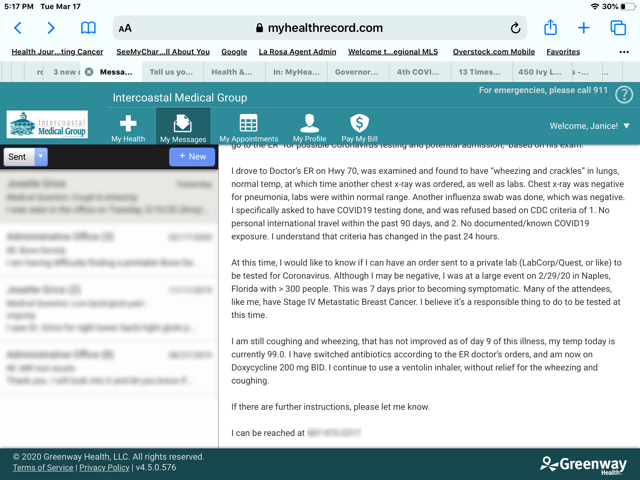

Cowden messaged her primary care physician through the patient portal on March 16, nearly a week after her initial appointment:

“At this time, I would like to know if I can have an order sent to a private lab (Labcorp/Quest, or like) to be tested for coronavirus. Although I may be negative, I was at a large event 2/29/20 in Naples, Florida with > 300 people. This was 7 days prior to becoming symptomatic. Many of the attendees, like me, have stage 4 metastatic breast cancer. I believe it’s a responsible thing to do to be tested at this time.”

The coughing and labored breathing had yet to stop. It was Day Nine of her ordeal.

The response was illuminating:

Intercoastal Medical Group, which has more than 50 primary care physicians, had only received 10 testing kits. As of March 18, the location where Cowden receives care had not yet been given a single test kit, a physician wrote to Cowden.

What happens next?

The first death from coronavirus in Manatee County, where Cowden lives, occurred March 17.

At this writing, there are 432 documented cases of COVID-19 in Florida, and Cowden isn’t one of them, even if she has the disease.

When she spoke on the phone with this reporter, the conversation was interrupted by bouts of coughing.

“Of course I will self-quarantine as long as the guidelines and the restrictions are in place that have asked all citizens to quarantine,” Cowden said. “But even my own family, I mean, my husband—has he been exposed or has he not? And have all of my friends been exposed that I was around, or have they not?

“I have many friends who live here, between being on rheumatoid arthritis medicines, and all different conditions,” Cowden said. “I have friends who are older than me, who are high-risk. If they get sick, what happens to them if this doesn’t change?”