In 2021, The Cancer Letter launched the Cancer History Project, a first-of-its-kind collaborative archive of oncology’s history.

As we saw it, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the signing of the National Cancer Act of 1971 was only the beginning of the project. The vision was broader: to see how the work of scientists and policymakers created today’s cancer program.

“Historical documents have a way of vanishing. Manuscripts, letters, and photographs end up in city dumps. Memories become less granular, insight is lost,” wrote Cancer History Project co-editors Paul Goldberg, who also serves as editor and publisher of The Cancer Letter, and Otis W. Brawley, Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Oncology and Epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University. “Cancer research, a field of science that half-a-century ago was assigned top priority under the National Cancer Act of 1971, must not be allowed to lose connection with history.”

In 2024, the Cancer History Project found new ways to explore the field’s history:

By training our sights on historic moments in oncology, we put together a series delving into how the discovery of the EGFR mutations dramatically changed lung cancer treatment in the past 20 years.

This multimedia series is guest-edited by Suresh S. Ramalingam, a lung cancer expert, executive director of Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, and editor-in-chief of the journal Cancer and consists of opinion pieces, historical documents, The Cancer Letter’s in-real-time-coverage, and interviews with scientists, clinicians, drug regulators, and cancer survivors.

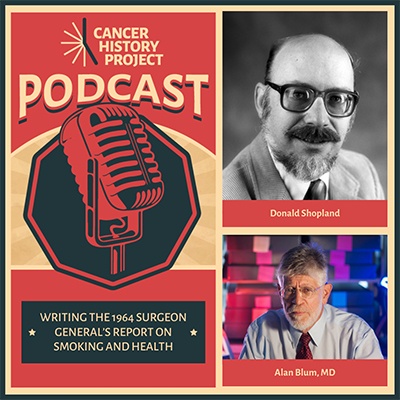

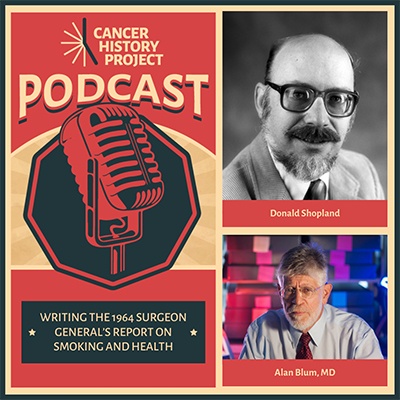

Another series, marking the 60th anniversary of the publication of the 1964 Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health drew attention—and featured The Cancer History Project’s top podcast episode of 2024: Don Shopland, Alan Blum discuss the writing of the 1964 Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health.

“Like anybody else that was around at that time, if you were a smoker, you didn’t want to believe this stuff,” said Shopland, an original member of the staff of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General upon its formation in 1962. “And they weren’t any different than the general public was, but it took them a good two months, or two committee meetings, before they actually got deep enough into some of the discussions about some of the data before they themselves decided that if they were going to answer this question, they were going to have to go a lot deeper than what the Public Health Services expected them to do, and come up with something a lot more detailed than something like the Royal College of Physicians.”

It’s clear both lay audiences and professionals in oncology are drawn to this history—in the last year alone, readership of the Cancer History Project has doubled.

Other notable highlights from this year’s most-read stories include:

- Latino oncology leaders discuss representation in clinical trials, translational research, and health care

- Susan Ellenberg started out as a high school math teacher—then became a leading biostatistician

- 2024 Karnofsky Award winner Lillian Siu talks about her career in phase I studies, ctDNA, & her mentor’s evil red pencil

Some articles appear in the most-read articles every year.

Jane Cooke Wright, a Black woman who was among seven founders of ASCO, appears in two articles every year: a eulogy and a photo archive.

Since The Cancer Letter has been keeping the real-time record of oncology, the Cancer History Project often refers to our own past coverage.

An unusual story from 1974 about an NCI press conference announcing the latest findings in breast cancer treatment—which coincidentally took place while First Lady Betty Ford was recovering from her mastectomy—has evolved into a multifaceted, multimedia, interconnected story spanning decades of coverage with characters including Bernie Fisher, Betty Ford, Happy Rockefeller, Rose Kushner, and Nancy Reagan.

This year, Less Radical, a podcast by radiation oncologist Stacy Wentworth, clinical associate in the Department of Radiation Oncology at Duke University School of Medicine, delves deeper into the story.

Other highlights include institutional histories submitted by the Cancer History Project’s 58 contributors. These include histories of Sarah Cannon, City of Hope, the American Cancer Society, and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

A list of the Cancer History Project’s most-read stories, grouped by topic, follows:

2024 highlights

Christy Erickson’s cancer diagnosis led to life as a motorcyclist and strongman competitor

Christy Erickson was seven years old when her mom lost a three-year battle with breast cancer.

“Most of my memories of her are of her being in some form of treatment,” said Erickson, who is currently a stay-at-home mom of two teenagers in Macon, Georgia.

Erickson grew up knowing that she might face the same fate as her mom. Breast cancer had a stronghold on Erickson’s family tree, so discussions of mastectomies and BRCA testing were common in her childhood home.

In 2000, when Erickson was 25, she visited a breast specialist to discuss her potential risk for breast cancer. She feared that she would put her soon-to-be husband and future children through the same difficulties that she had experienced with her mom. Although Erickson had tested negative for BRCA mutations, the specialist recommended that she receive a baseline mammogram that day.

During the appointment, an ultrasound uncovered a pea-sized lump in one of her breasts.

Latino oncology leaders discuss representation in clinical trials, translational research, and health care

Hispanic and Latino people comprise nearly 20% of the U.S. population, but less than 6% of physicians nationwide identify as Hispanic.

“The pipeline issue continues to be a huge issue for us,” Amelie Ramirez, of UT Health San Antonio and Mays Cancer Center, said during a panel discussion convened by The Cancer Letter to mark Hispanic Heritage Month. “As our population continues to grow, in terms of the Latino population, we definitely need more [Latino physicians].”

Ramirez joined five other cancer experts for a conversation about cancer in Latinos, health equity, and how to support Latino clinicians and researchers. The discussion was moderated by Ruben Mesa.

Susan Ellenberg started out as a high school math teacher—then became a leading biostatistician

John is twice Mary’s age when John was Mary’s age. When Mary will be John’s age, the sum of their ages will be 63. How old are John and Mary?

Susan Ellenberg occasionally chipped away at the question laid out by her father, a CPA, by randomly plugging in numbers. But soon, she discovered another way to approach it.

“When I got to high school algebra, I learned that there was an actual way to solve this problem. I was so excited I knew how to do it,” Ellenberg, emerita professor of biostatistics, medical ethics, and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, said on the Cancer History Project podcast.

“With my algebra homework, I would often do more problems than were actually assigned because I just thought it was so cool that there was an actual way to do this and not just do trial and error and guess,” she said.

Ellenberg never intended to become a researcher, or even end up in statistics—a STEM field that has been welcoming to women for a long time.

“It wasn’t that way in mathematics, certainly. But in statistics, it was more friendly,” Ellenberg said.

60 years after: Don Shopland, Alan Blum discuss the writing of the 1964 Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health

In 1964, the Office of the Surgeon General issued a report on smoking and health that ended a debate that had raged for decades—stating that cigarettes cause lung cancer and other diseases.

Sixty years later, Alan Blum, professor and Gerald Leon Wallace, MD, Endowed Chair in Family Medicine at the University of Alabama, as well as the director of the Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society, warns against celebrating the anniversary of the report.

“I should be clear that I would prefer to call this a commemoration,” Blum said in an interview with Donald S. Shopland, an original member of the staff of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General upon its formation in 1962. “A celebration would suggest everything is happy, because I think this is a more nuanced subject.”

This interview is available as a podcast through the Cancer History Project.

Related:

- Excerpt of “Blowing Smoke: The Lost Legacy of the Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health”, By the Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society, Jan. 11, 2024

- Former HHS Secretary Louis Sullivan recalls sinking RJR’s “Uptown,” a menthol brand for Black smokers, Jan. 19, 2024

Discovery of EGFR mutations dramatically changed lung cancer treatment

20th anniversary of landmark findings

By Suresh S. Ramalingam, MD

When I started fellowship training in the year 2000, the response from everyone when I mentioned my interest in lung cancer was nearly the same: “Are you sure?”

This experience was not unique to me; every thoracic oncologist at that time would likely relate to that. The basis was not hard to understand: lung cancer was a highly lethal disease, with practically one proven chemotherapy agent (platinum) that improved the 1-year survival rate by 10% for patients with stage 4 disease.

Even in uncommon situations where lung cancer was diagnosed at an early stage, survival was suboptimal despite complete resection. The stigma associated with tobacco smoking, lack of treatment options, and high mortality were driving the widespread nihilism for lung cancer.

It was not uncommon for patients to be directly referred to hospice following the diagnosis of lung cancer. In fact, the “Big Lung Trial” (published in 2004) compared platinum-based chemotherapy to best supportive care and demonstrated a 9-weeks improvement in median overall survival with the former. It hardly mattered if a patient had non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (~85%) or small cell lung cancer (~15%).

Related:

- Series: 20 Years of EGFR

- Iressa: Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting Sept. 24, 2002

- Tom Lynch reflects on discovery of the EGFR mutations’ role in lung cancer, Oct. 4, 2024

Who Is Bernie Fisher?

By Less Radical

Our story begins exactly fifty years ago. On a fall weekend in late September 1974, a former dancer from Michigan and a young surgeon from Pittsburgh met just outside Washington, DC. The treatment of breast cancer would never be the same.

“Less Radical” is the story of Dr. Bernie Fisher, the surgeon-scientist who not only revolutionized breast cancer treatment, but also fundamentally changed the way we understand all cancers. He was an unlikely hero—a Jewish kid from Pittsburgh who had to make it past antisemitic quotas to get into med school. And the thanks he received for his discoveries? A performative, misguided Congressional hearing that destroyed his reputation and haunted him until his death.

Over six episodes, radiation oncologist Dr. Stacy Wentworth will take you into operating rooms, through the halls of Congress, and into the labs where breakthrough cancer treatments were not only developed, but discovered.

If you or someone you know has had breast cancer, Bernie is a part of your story—and you’re a part of his.

Related:

- Less Radical podcast

- How First Lady Betty Ford and surgeon Bernie Fisher revolutionized America’s attitude toward breast cancer, by Stacy Wentworth, MD, Sept. 27, 2024

- Cancer History Project Panel: How Betty Ford’s and Nancy Reagan’s breast cancer diagnoses changed attitudes to cancer, March 10, 2023

- Breast cancer in the White House: Nabby Adams, Betty Ford, Happy Rockefeller, and Nancy Reagan, by Stacy Wentworth, MD, March 3, 2023

Before her legendary career at NIH, Vivian Pinn was the second Black woman to graduate from UVA med school

As a student, the first director of the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health helped desegregate Charlottesville

On her first day of medical school at the University of Virginia in 1963, Vivian Pinn waited for the other students who looked like her to show up.

“The other women and other people of color must be late,” she remembers thinking, glancing around at the crowd of white men in the auditorium before her.

Then they called the roll.

“And I’m sitting in the back and I see, everybody’s there,” she said in a conversation with Robert Winn, director and Lipman Chair in Oncology at VCU Massey Comprehensive Cancer Center, and senior associate dean for cancer innovation and professor of pulmonary disease and critical care medicine at VCU School of Medicine.

Related:

- Roderic Pettigrew, founding director of NIBIB, reflects on a career as a “physicianeer”—merging medicine, engineering, Feb. 23, 2024

2024 Karnofsky Award winner Lillian Siu talks about her career in phase I studies, ctDNA, & her mentor’s evil red pencil

Lillian L. Siu discovered her passion while perusing employment ads in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“I literally opened JCO, the Journal of Clinical Oncology, one day, and in the back there was an advertisement for a drug development fellowship in San Antonio, Texas. I read the description and felt, ‘Wow, this is really what I want to do. I want to develop drugs and bring new drugs to patients and bring them hope,’” Siu, director of the Phase I Clinical Trials Program and clinical lead of the Tumor Immunotherapy Program at University Health Network’s Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, said on the Cancer History Project Podcast. “It opened my eyes that this is definitely a field that I would love to be involved in—to take a drug from bench to bedside and then translate back to understand why it works or it doesn’t work.

“To me, that was, ‘Wow, I would love to spend my whole career doing this.’ And I did.”

How “Dr. Susan Love’s Breast Book” has remained the “bible” for women with breast cancer since 1990

When Stephanie Graff was a breast oncology fellow in 2010, one of her patients brought a marked up copy of “Dr. Susan Love’s Breast Book” to an appointment.

“One of my patients had brought it in and was using it almost as her cancer notebook, and had pages flagged and said, ‘Well, what about this? What about this? It says here…,’” Graff, director of Breast Oncology at Lifespan Cancer Institute and medical advisor to Susan Love’s foundation, said to The Cancer Letter.

The Dr. Susan Love Foundation for Breast Cancer Research is now the Dr. Susan Love Fund for Breast Cancer Research at Tower Cancer Research Foundation.

It was the first time that the book, written by Susan Love, a breast cancer surgeon, activist, and founder of the Dr. Susan Love Foundation for Breast Cancer Research, had shown up on Graff’s radar.

“Dr. Susan Love’s Breast Book,” which sold a half-a-million copies and was dubbed the “de facto bible for breast cancer patients” in The New York Times, also became an essential part of Graff’s oncology education.

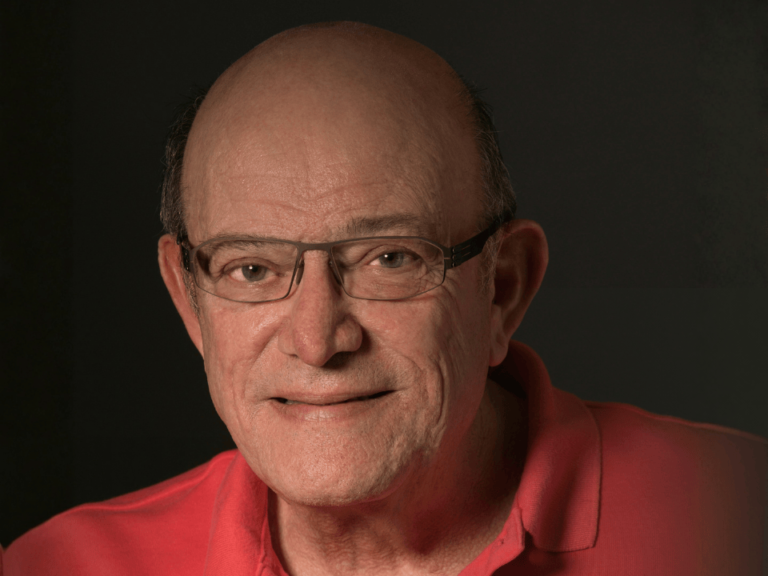

Weeks before death from sarcoma, Norm Coleman reflects on career in radiation oncology, addressing health disparities

Soon after he was diagnosed with a dedifferentiated liposarcoma, C. Norman Coleman reached out to The Cancer Letter and the Cancer History Project to initiate a series of interviews about his life and career.

“I don’t know how much time I have,” Norm said during the first interview.

The plan was to keep going for as long as possible. Alas, only one interview–about an hour’s worth–got done.

Coleman died March 1 at 79 (The Cancer Letter, March 8, 2024).

Colleagues say Coleman was working on a manuscript two days before he died.

At NCI, Coleman was the associate director of the Radiation Research Program, senior investigator in the Radiation Oncology Branch in the Center for Cancer Research, and leader of a research laboratory at NIH.

He was also the founder of the International Cancer Expert Corps, a non-profit he created to provide mentorship to cancer professionals in low- and middle-income countries and in regions with indigenous populations in upper-income countries.

From the archives

Some stories come back every year.

Exhibit: When cigarette filters were made of asbestos

By the Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society

Excerpted from the Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society’s online exhibit on the Micronite cigarette filter.

In 1952, using the popular new medium of television, the P. Lorillard Tobacco Company sponsored “scientific” demonstrations to show the efficacy and implied health benefits of its KENT Micronite filter. The campaign also featured advertisements in medical journals. Although the ads did not disclose the composition of “Micronite,” the material that Lorillard touted as “so safe, so effective it has been selected to help filter the air in hospital operating rooms” and that was used “to purify the air in atomic energy plants of microscopic impurities” was asbestos. This exhibition features a display of the KENT Micronite filter created in 2005 for the Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society by asbestos expert Anthony G. Rich.

Related:

- The boy who cried vape: Philip Morris International calls for a smoke-free world, Jan. 19, 2024

- A Vote for Cancer: Tobacco Advertising and Presidential Elections, Oct. 25, 2024

- Smoke rings: Tobacco and the Olympics, July 26, 2024

- How tobacco companies sold women a pack of lies, Nov. 2, 2023

Chris Lundy had one week to live; 52 years later, he is the longest living BMT recipient at the Hutch

At 75, Chris Lundy is one of the longest living recipients of a bone marrow transplant.

He was among the patients included in the 1975 paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine titled “Bone-Marrow Transplantation.”

“It was a paper everyone interested in bone marrow transplantation read word for word,” Frederick Appelbaum, executive vice president, professor in the Clinical Research Division, and Metcalfe Family/Frederick Appelbaum Endowed Chair in Cancer Research at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, wrote in his book “Living Medicine.” “It was the article that introduced marrow transplantation to the general medical community.”

How Beth Carner went from six weeks left to live with stage 4 colon cancer to complete remission

At 25, Elizabeth Carner was diagnosed with stage 4 colon cancer.

“I mean, the first thing that went through my head was just looking at mom and dad, and it’s just like, OK, well, where did all the other stages go? Because we literally went from my colonoscopy as being OK to everything’s not OK,” Carner, now 33, said to Deborah Doroshow, an oncologist at the Tisch Cancer Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

At the time, Carner, who studied theater and stage management as an undergraduate, had a coveted job at an equity theater, Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park. She hadn’t thought much of her recent weight loss before the diagnosis—going from 175 to around 150—chalking it up to the hustle of theater life.

Then, one day, Carner fainted at work.

Remembering Jane Cooke Wright, a Black woman, who was among seven founders of ASCO

Edith Mitchell: Good afternoon.

It is a great privilege and honor to have the opportunity to represent the National Medical Association in this tribute to Dr. Jane Cooke Wright. I first met Dr. Wright during as ASCO meeting and maintained subsequent contact.

She is affectionately known in the cancer research community as the Mother of Chemotherapy. She is not only known as the Mother of Chemotherapy, but Dr. Wright is listed in the Women Pioneers of Medical Research and among the top Medical Researchers.

Related:

Cancer as ancient Egyptians knew and understood it

By Jaya M. Satagopan, PhD

When do you think the first evidence of cancer in humans was recorded?

The earliest written observation of cancer in humans comes from Egypt, although the word cancer was first used by Hippocrates much later. The Edwin Smith Papyrus, the oldest known surgical treatise on trauma, is a collection of 48 medical cases of injuries. The Papyrus, which is presumed to have been written by the architect-physician-statesman Imhotep, dates back to the Pyramid Age (around 3000 – 2500 BC) and provides the earliest description of human tumor. The historic two-volume translation of the Papyrus by James Henry Breasted in 1929 offers a fascinating window into the practice of medicine and early evidence of tumor in ancient Egypt.

The Papyrus provides case studies of several breast tumors.

John Laszlo’s dual role: (1) Working to cure childhood leukemia, and (2) Writing the authoritative book on it

His father, Daniel Laszlo, did early work on folate antagonists

When John Laszlo joined the Acute Leukemia Service at NCI in 1956, the field of oncology was nascent—and the cure for childhood leukemia seemed beyond reach.

“It was a time that these children were just not going to do well. You knew that walking in,” Laszlo, 92, professor emeritus at Duke University Medical Center and a retired national vice president for research at the American Cancer Society, said to The Cancer Letter. “It was very challenging to deal with children who were bleeding from the nose, who were bleeding from the rectum, who were vomiting—and parents were hovering about, very concerned about their children.”

Laszlo worked directly with Emil “Tom” Frei, and Emil J Freireich—early researchers and doctors of childhood leukemia at NCI. Their team tried as best they could to help children as young as three. They stopped the bleeding, gave them antibiotics, and packed their noses.

“Most of them you couldn’t help at that stage of the game,” Laszlo said. “It’s very gratifying to think about all the progress that’s been made since those early days of taking care of these tiny children who didn’t know what was wrong, why they were there, why their parents were not with them.”

Related:

- The Cure of Childhood Leukemia: Into the Age of Miracles, by John Laszlo. Available as an e-book.

The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident: 10 years later

By Robert Peter Gale, MD, PhD

On the early morning of March 11, 2011, I was on an elliptical trainer in the health club of my Paris hotel watching CNN when I saw live coverage of a powerful earthquake in Japan.

A slow-moving wave about 1 m high came sweeping up a river, overspilled the embankments and inundated the land. People were running to climb a highway overpass whilst cars swept by like toys.

The 9.0 Richter scale earthquake about 70 km off the northern Tohoku coast of Honshu, the main Japan island, triggered a tsunami with 40 m tall waves—a 12-story building—reaching 9 km inland. My concern at the time was for my colleagues at Tsukuba University about 300 km south of Sendai.

The three comprehensive cancer centers that set the model for a nation

Directors of the first three NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers are learning from the past, starting with the National Cancer Act, and mapping an equitable future for oncology.

On July 29, 2021, the Cancer History Project convened panelists Candace S. Johnson, president and CEO of Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Craig B. Thompson, president and CEO of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and Peter WT Pisters, president of MD Anderson Cancer Center, for a two hour Zoom session moderated by co-editor Otis W. Brawley.

Simone’s Maxims: Understanding Today’s Academic Medical Centers

Joseph V. Simone, a visionary physician-scientist and writer of guidelines and maxims, died on Jan. 21. He was 85.

To celebrate Joe’s life, his family is allowing The Cancer Letter and the Cancer History Project to make Simone’s Maxims available in electronic form. The book continues to be available in paperback from Editorial Rx Press.

“Simone’s Maxims” is a book so fundamental to academic oncology that we don’t know when we are stealing Joe’s lines.

Here are three of Joe’s most famous maxims:

- Institutions don’t love you back.

- Leadership does matter.

- Contrary to the laws of physics in academic institutions, crap flows uphill.

Harold Freeman, father of patient navigation, on cutting the cancer out of Harlem

Harold Freeman had big plans after he finished his residency at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in 1968. He planned to cut cancer out of Harlem.

“I’m ready to do it. I’m skilled. I know how to cut cancer out. I want to cut it out of Harlem. I can’t do that. I can’t cut it out. It won’t yield. It won’t yield to the surgeon’s knife. It won’t yield to what we call the Bard-Parker, which was the name of the surgeon’s knife. Cancer wouldn’t yield,” Freeman said in an interview with Robert A. Winn, director of VCU Massey Cancer Center, and John Stewart, founding director of LSU Health/LCMC Health Cancer Center. “Then I get to the reality, I can’t cut it out. Why? Because the people were coming in too late with cancer for me to be able to cut it out.”

Freeman made his career out of asking why it was that his patients, who were poor and Black, sought treatment too late. As president of the American Cancer Society in 1988-89, he published a study, “Cancer in the socioeconomically disadvantaged,” and made an unprecedented conclusion—“that the principal reason that Black people were dying from cancer was because they were poor.”

Institutional histories

Sarah Cannon: The Name & The Story

Sarah Cannon was the real name of the television and radio personality, Minnie Pearl. Sarah Cannon received treatment for breast cancer at the founding center in Nashville. Afterwards, she offered the use of her name to promote cancer research and patient education with a vision of offering patients convenient access to early detection, clinical trials and a team approach to cancer care.

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital celebrates 60 years of saving children’s lives

When St. Jude founder Danny Thomas opened St. Jude on February 4, 1962, he created an organization as rare today as it was then: a research hospital where children with catastrophic diseases receive free cutting-edge medical care.

St. Jude is celebrating its 60th anniversary with a year-long slate of events commemorating the legacy of advances in the understanding and treatment of pediatric cancer and other deadly diseases. As one of the largest and most beloved health care charities in the country, St. Jude is a unique organization, blending clinical care with scientific research. At the same time, the organization’s leaders are laying the groundwork across scientific, clinical and global operations that will prepare the institution for another 60 years.

The Story of City of Hope

In 1913, tuberculosis would kill nearly 150,000 people, more than twice the toll taken by cancer. A group of committed volunteers refused to accept this tragedy and established the Jewish Consumptive Relief Association (JCRA), a free, nonsectarian tuberculosis sanatorium.

After hosting several fundraisers, the JCRA placed a down payment on 10 acres of sun-soaked land in Duarte, California, where they would establish the Los Angeles Sanatorium a year later. The original sanatorium consisted of two canvas cottages and ultimately launched a century-long journey that would place City of Hope at the forefront of the nation’s leading medical and research institutions.

Their visionary efforts were rewarded when, by the mid-1940s, the discovery of antibiotics pushed tuberculosis into a decline across the United States. But there was no time for celebration. The pioneering thinkers at City of Hope had already trained their focus on humanity’s next great medical challenge: tackling the catastrophic disease of cancer. Later, they mounted a fight against diabetes and HIV/AIDS. In accepting each new medical challenge, however daunting, City of Hope continually reaffirms its humanitarian vision that “health is a human right.”

In the spirit of that remarkable cause, Samuel H. Golter, one of City of Hope’s early leaders, coined the phrase, “There is no profit in curing the body if, in the process, we destroy the soul.”

American Cancer Society Marks 110th Year

The year was 1913. At that time, a cancer diagnosis meant near-certain death for patients, and the word “cancer” was often met with fear or denial.

That reality is what prompted the creation of a group that would draft a plan for a comprehensive cancer education program. A group of advocates, 10 doctors and five laypeople, held an organizational meeting in May 1913 at the Harvard Club in New York City. That meeting launched the creation of the American Society for the Control of Cancer (ASCC), the organization that would one day become the American Cancer Society.

Related:

- The history of Relay For Life, by the American Cancer Society, April 13, 2023

- A Look Back at the Great American Smokeout, by the American Cancer Society, Nov. 15, 2022

MSK’s Sloan Kettering Institute Celebrates 75 Years of Discovery

When the Sloan Kettering Institute opened its doors on Friday, April 16, 1948, an Associated Press wire story announced: “The world’s greatest cancer center opened here today.”

And over the last seven and a half decades, institute researchers have made important contributions to the fundamental understanding of human biology, as well as driven practice-changing innovations in the treatment of cancer.

Sloan Kettering Institute scientists have discovered cancer-linked genes, unraveled signaling pathways that control cell growth and division, and identified cells involved in mounting and repressing immune responses.

They’ve illuminated how vesicles transport molecules to the surface of cells for secretion — work that later went on to earn a Nobel Prize. They’ve figured out how to derive dopamine-producing neurons from human embryonic stem cells, setting the stage for new treatments for Parkinson’s disease. And they’ve uncovered an overlooked alternative to the famous Krebs cycle, the main process that supplies the energy needs of cells — to list just a few examples.

And they’ve helped pioneer major advances in cancer treatment, from developing some of the first effective chemotherapy drugs to making significant contributions to today’s cutting-edge immunotherapies.