Hundreds of women were injured or have died from upstaging of unsuspected uterine cancer by power morcellation because FDA didn’t know the actual risk of cancer in fibroids, and hospitals failed to report harm, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

Between 1991 and 2014, FDA cleared 25 submissions for power morcellators to be marketed in the U.S. The GAO report notes that FDA had been aware of the device’s potential for spreading tissue since 1991.

The agency didn’t receive reports of adverse events—which the federal government requires of hospitals and device manufacturers—resulting from power morcellators until December 2013. An FDA inspection of 17 hospitals in December 2015 found that the vast majority of these institutions did not file timely reports of injuries and deaths caused by medical devices.

“I do think it was a failure of the adverse event reporting system, yes. I think it’s a failure because reports were not being filed,” said Marcia Crosse, director of the health care team at the GAO. “The problem here was a failure to have an accurate estimate of the frequency with which there is an undiagnosed leiomyosarcoma in what is believed to be a uterine fibroid, a benign fibroid.”

Marcia spoke with Matthew Ong, a reporter with The Cancer Letter.

Matthew Ong: In your opinion, what is the most significant finding of the GAO report on power morcellators?

Marcia Crosse: Well, I would say that I think it points to the weaknesses in the passive surveillance system, that so many years went by before any reports were submitted to FDA.

According to congressional critics of power morcellators, “hundreds, if not thousands of women in America” have been harmed or have died over the past 20 years because of this device. Based on your investigation, is this an accurate statement?

MC: While we’re aware of 285 adverse event reports that were filed with the FDA, we are not making any independent estimate of the number of women harmed.

Certainly, the hundreds seem reasonable, I cannot say thousands. I don’t have data about the frequency of the procedure, and we did not make any estimates of how many women may have been harmed. I’m not extrapolating. That’s a question for FDA.

Are you concerned about other devices doing similar grave harm?

MC: I don’t know about the same kind of harm. Certainly, we have seen several examples of devices where it has been some time before problems are identified.

There’s the duodenoscopes, and so the extent to which they might not have been properly cleaned, I think, was not well recognized and it took some time for that to be identified.

And again, that’s another area where reports were not being filed, that the passive surveillance systems seems not to have worked as quickly as one would hope. And then the metal on metal hips.

So there certainly are several examples where large numbers of patients have been treated and certainly have been potentially exposed to harm. We have not studied the full range; there are so many medical devices.

Obviously the fact that there are so many medical devices and you don’t see more of these, I think, means that things are not in complete breakdown, but we see more examples than we’d hope to.

Does this regulatory issue have implications for other devices and other patient cohorts?

MC: I don’t want to speculate on what other devices might have similar kinds of problems. I think, certainly, the issue of a passive surveillance system is true for virtually all devices. And so, to the extent that there are unrecognized problems, then this kind of issue could recur.

They are taking some additional steps now. For example, the Unique Device Identifiers that might allow for better tracing of patients and then for case identification. If some reports are filed, then that might facilitate the ability to go back and look and see if there were additional cases.

So I would say that there is some movement in the right direction, and they are trying to take some steps towards building better data systems to be able to do some case finding. But they’re not there yet.

What is the root cause of this problem, and why do you think the harm caused by these devices had gone unnoticed and unreported for so long? Is this a failure in reporting?

MC: I do think it was a failure of the adverse event reporting system, yes. I think it’s a failure because reports were not being filed.

The law requires hospitals/user facilities and device manufacturers to report adverse events caused by medical devices. Are these reporting requirements adequate and sufficient?

MC: I think FDA’s investigation and the warning letters that they issued showed that there was more room for enforcement of those requirements, because, clearly, there was a failure to comply at many institutions.

Right, the agency inspected 17 institutions in December 2015.

MC: And they haven’t looked at the full range of institutions. It’s not as though they are going out every year and doing these kinds of reviews at hospitals, nor do they have the resources to be able to do that.

And so they have been reliant upon the good faith and execution of those requirements by the medical establishment. I think this points to a breakdown at some very prominent hospitals in their compliance with these requirements.

This issue came to light because two affected physicians reported the problem to the FDA. Could this problem have been avoided if individual physicians had a specific responsibility to report adverse outcomes associated with medical devices?

MC: I don’t know. That’s speculation. I don’t know. I think if FDA had been aware of it sooner, it could have taken action sooner.

I don’t know if the entire problem could have been avoided by that, because clearly there was some recognition of this risk when the devices were first approved. Just the magnitude of the risk was not well understood.

As you know, FDA is in the process of creating an intensive surveillance system to protect patients from high-risk medical devices.

MC: Right, that’s what I was describing before.

Critics say this will take several years to implement, potentially leaving patients at risk. Last year, there was a bill in the House called the Medical Device Guardians Act that would require individual practitioners to report adverse events without fear of liability. Would this be an effective strategy to give FDA access to high quality signals from physicians?

MC: It’s not appropriate for me to comment on proposed legislation. We are a support agency for the Congress and we were not asked to review that legislation and the likely impact of it. So I would just be speculating. I don’t really have a position on that.

Power morcellators are still on the market. Are you concerned about them being used?

MC: I think, as with any medical procedure, there are risks, and it’s appropriate for patients to have conversations with their physicians about what’s the best approach for their individual treatment.

There certainly are concerns that we heard about from not using power morcellators, from doing an open procedure, which can carry different kinds of risks.

And so, we are not saying that these devices should never be used. That is not our call to make. That’s a call to be made between the practitioner and the patient.

The 510(k) clearance process for Class II medical devices did not account for the potential for power morcellators to cause harm, and was not sensitive to signals of harm for over 20 years. What is the problem here? Is this device an anomaly? Would classifying the power morcellator as a class III device have brought the oncological hazard to light earlier? Is this a classification issue? Or is the 510(k) a flawed process that should be revisited?

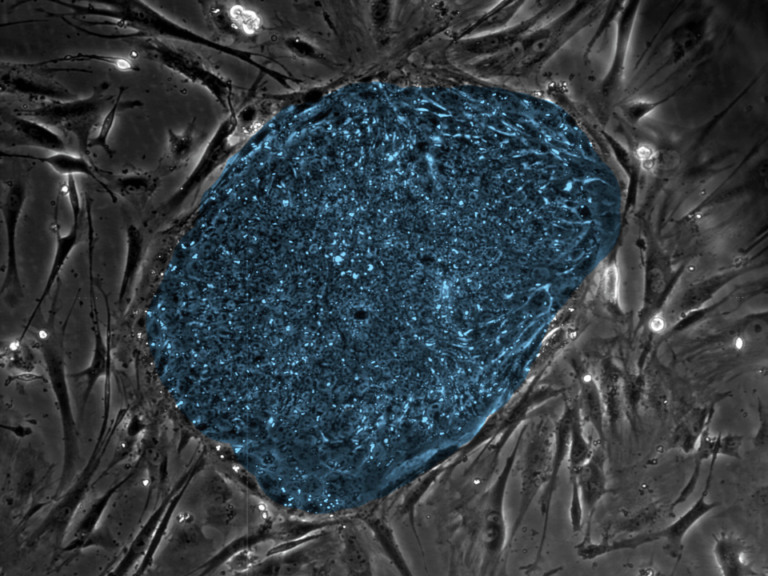

MC: I would pick none of the above. I think the problem here was a failure to have an accurate estimate of the frequency with which there is an undiagnosed leiomyosarcoma in what is believed to be a uterine fibroid, a benign fibroid.

So it is not that the device didn’t work as it was intended to work, it is not that the device broke, or failed in carrying out the surgery as it was intended to be used.

There’s no evidence that it was not an appropriate choice to use a 510(k) pathway, that this device posed any more risk that the predicate devices upon which it was based, or that other devices used in laparoscopic surgery shouldn’t be going through a 510(k) process.

I think the failure here was a lack of information and understanding of the underlying risk posed by use of the device when a cancerous tissue was present. And that’s more of an epidemiological issue than a 510(k) process issue.

Critics have said that if this device, instead of being cleared through the 510(k) pathway, was reviewed through the Class III premarket approval process—which assesses for risk—the PMA might have caught the signal earlier. Is this pertinent?

MC: I don’t know that I fully agree with that. I think that you would have to have the data, and I’m not sure that … I don’t know if it would have been identified.

The House members who requested the report did not ask for recommendations from your team. Imagine a hypothetical situation where you are asked to present recommendations: what would your recommendations be?

MC: We would have made recommendations if we felt recommendations were warranted. We don’t have to be asked to make recommendations.

We felt that FDA had taken and was taking appropriate steps. They had put out information about this. They had requested labeling changes from manufacturers and manufacturers had made those labeling changes.

And they had undertaken a review to develop a better estimate of the underlying risk. They had taken the kinds of steps that we potentially could have recommended, had they not already been done.

But we make recommendations to the government. We would not make recommendations to hospitals, for example, for what they should be doing. That’s not an appropriate function for us.

So I think that the gaps that we see as remaining are gaps in reporting by the medical establishment. And that’s not something that we have. Our recommendations are to federal agencies.

We felt that FDA had, now, taken appropriate steps and we had no further steps we thought they needed to be undertaking that they were not on the pathway to do.

Going forward, will FDA’s action on this issue—with the new surveillance system and the Unique Device Identifiers—create an improved signaling system for adverse events caused by medical devices?

MC: I think that they are taking steps that are certainly in the right direction. I think it’s too soon to know how much more effective it will be.

Did I miss anything, and do you have any closing comments?

MC: I don’t think so, no. I think this certainly points to, as I said at the outset, this larger concern about the reliance of the system upon the medical establishment to report instances of problems to FDA when they’re identified. In this situation, I think that the medical establishment has not been thinking of adverse events, perhaps, in a broad enough way.

If the device had broken in the middle of a surgery, if the device had left a piece behind, the tip had fallen off or something like that, I think that the medical establishment is used to thinking of those kinds of device-related events as adverse events to be reported. They may not be accustomed to thinking—and they need to think more broadly—that the device can work as it was intended to work and still cause harm.

I think that was not, perhaps, being recognized sufficiently. There are folks in large medical centers charged with responsibility for this reporting, and so I’m hoping this was a wake-up call.