Testing of chemicals for potential cancer causation (carcinogenesis) has long been a successful disease-prevention initiative of the highest priority.

Even before the 1970s “War on Cancer,” the National Cancer Institute, other U.S. Government agencies, and many universities were heavily invested in the identification of potential carcinogens. However, because of recent Federal actions, carcinogen exposures and subsequent cancer rates could increase over the next few decades, resulting in otherwise preventable disease and increased medical costs for the general public.

How we identified carcinogens in the past

For almost a century, the United States government has been a leading organization within the World Health Organization in identifying cancer-causing exposures including drugs, pesticides, natural products, industrial chemicals, air pollution, and many other types of agents.

Because of recent Federal actions, carcinogen exposures and subsequent cancer rates could increase over the next few decades, resulting in otherwise preventable disease and increased medical costs for the general public.

In 1971, carcinogen surveillance was mandated by Congress with the passage of the “National Cancer Act”.

In the early 20th century, carcinogens were originally identified through human epidemiological (population) studies where cancer incidences and deaths were tragically observed and eventually traced back to occupational, medical, lifestyle, or other exposures.

By the mid-20th century, long-term testing for tumor induction in laboratory rodents became the gold standard for carcinogen identification. Committees of scientists identified chemicals that were suspected human carcinogens, and the appearance of tumors in the test animals contraindicated human use. This type of testing was time-consuming and costly, but effective in protecting the population against many carcinogens.

Biomarkers and genetic toxicology

In the last approximately 50 years, potential carcinogenic risk has also been identified in laboratory animals and in in vitro test systems through biomarkers that do not require long-term studies. Some of these biomarkers involve analysis of DNA damage that can lead to changes in DNA sequence (mutations). It is well known that mutations in DNA can initiate downstream events that can lead to tumor formation.

The scientists who develop, employ, and interpret these biomarker analyses, genetic toxicologists, play an essential role in making sure that potentially carcinogenic agents are not licensed and do not reach the American public. Consequently, few agents are marketed that test positive for DNA damage/mutation because licensing applications are either not submitted or are rejected by the regulatory agencies for their potential hazard.

Examples of human success stories

Many potentially carcinogenic human exposures have been prevented by research at the FDA, EPA, NIH, and other U.S. Government agencies. Selected examples include identification of air pollution as a cause of lung cancer, tanning bed rays as a cause of skin cancer, aristolochia (a dietary herbal supplement) as a cause of kidney cancer, and asbestos as a cause of mesothelioma.

Other DNA-damaging/mutagenic human carcinogens include cigarette smoke, formaldehyde, radon, aflatoxins (from molds), and diesel engine exhaust.

We are concerned about the future

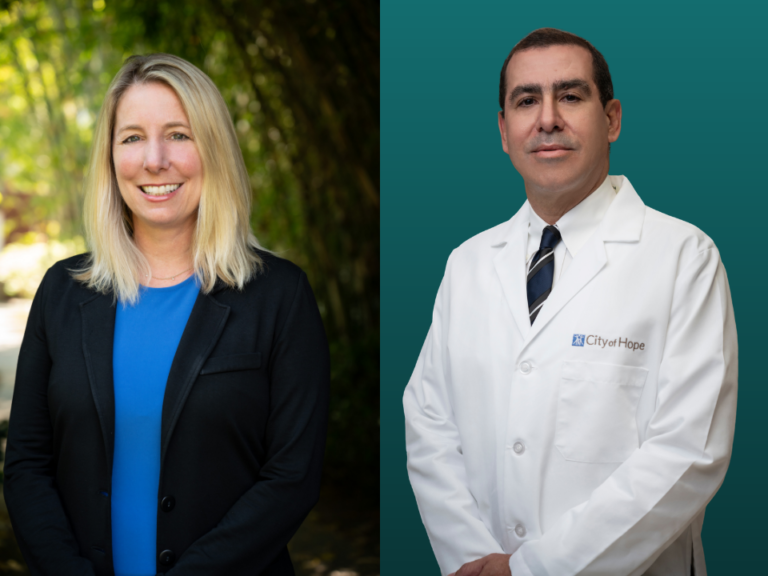

Having spent our careers studying DNA-damaging and mutagenic chemicals, we four and our colleagues have contributed to the protection and well-being of Americans. Collectively, the four of us have authored approximately 900 scientific publications. Also, we frequently participated in national and international evaluation panels to assess the capacity of many types of products to cause mutations and increase cancer risk.

Based on decades of experience, it is our opinion that, with the recent firing and/or forced retirements of early-career and senior federal researchers, there is now a diminished capacity to identify and protect Americans from new cancer-causing exposures.

Based on decades of experience, it is our opinion that, with the recent firing and/or forced retirements of early-career and senior federal researchers, there is now a diminished capacity to identify and protect Americans from new cancer-causing exposures.

The loss of surveillance and cutbacks to funding are particularly harmful for two reasons: 1) many cancers take years to appear after initial exposure, so the causes are difficult to identify; and 2) to train an independent cancer researcher takes about 15 years post-high school. This combination of reduced infrastructure (fewer experienced scientists) and long tumor latency (tumors appearing years after relevant exposure) will weaken our ability to respond at a time when increasing numbers of chemicals are entering our environment.

Furthermore, the dismissal of the youngest scientists who have knowledge of cutting-edge methods and enthusiasm for new developments will truncate the pipeline of scientific progress. The overall result will stymie the mission of biomedical research to serve Americans with the best science possible.

The bottom line

Going forward, we are concerned that a substantial reduction in personnel and resources for carcinogen surveillance may lead to late identification of future cancers, resulting in the potential for increases in cancer incidence and mortality, and an overall diminished capacity to keep Americans safe.

Footnote: This guest editorial was endorsed by the Environmental Mutagenesis and Genomics Society (EMGS), a 56-year-old organization that is the premier scientific society in North America focused on DNA damage and mutagenesis. Although this statement is endorsed by the EMGS, it does not necessarily reflect the opinions of all EMGS members. The four of us are EMGS members, and RE, DMD, and MCP are past Presidents of the EMGS. All of us are genetic toxicologists retired from EPA (DMD), FDA (RE), and NIH (MCP, EZ).