A recent analysis of the National Cancer Institute’s workforce and grant recipients shows that Black and Hispanic scientists are dramatically underrepresented across key metrics, both intramural and extramural.

To wit, only 1% of the institute’s prestigious R01 grants—Research Project Grants that provide researchers with multi-year funding and support—are awarded to Black scientists in FY2020. That meager proportion—1%—has not budged over the past 10 years.

Hispanic scientists received 5% of R01 grants. Combined, other groups, including American Indians, Alaskan Natives and Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders, added up to another 1%. Application rates are strikingly low across the board for all aforementioned minority groups.

Within NCI’s Intramural Research Program, only 1% of senior investigators are Black. Hispanic scientists make up 2% of that cohort. The statistic is dismal for Black faculty members, too—1%—among NCI tenure track investigators.

There are no Black and Hispanic senior scientists and clinicians at NCI.

For perspective, three quarters or more of the institute’s senior scientists and investigators are white. Nearly two-thirds of R01s are awarded to white applicants.

These findings were presented by NCI leaders at a June 14 joint meeting of the National Cancer Advisory Board and the Board of Scientific Advisors.

“We have really realized that it’s not enough to just talk about these problems, but we will actually have to use funds and use our authorities to try and address them,” NCI Director Ned Sharpless said to the institute’s advisors at the joint meeting. “And I hope that is clear in the presentations thus far.”

In a packed, hour-long three-part presentation by working groups, NCI leaders announced a comprehensive array of initiatives as demonstration of the institute’s commitment to mitigate cancer disparities and health inequities.

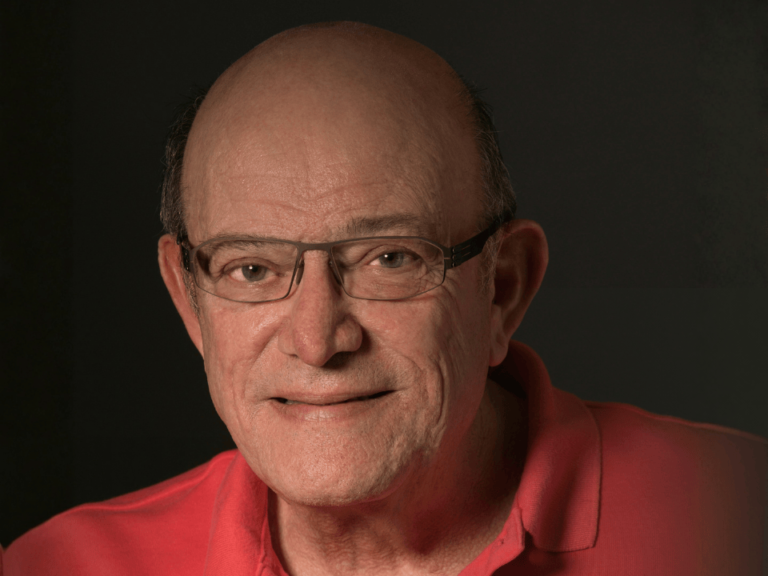

“At this time, more than ever, it’s imperative that we encourage everyone in the oncology community to think of issues of health equity,” said BSA member Otis Brawley, the Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Oncology and Epidemiology at The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins University. “It’s everyone’s responsibility, and we all need to think about it and about what we can do to promote health equity.

“It’s important that NCI is doing this because NCI has, in my mind, always been progressive in this area and has always been a leader—and has the opportunity to lead, not only in oncology, but also in medicine right now,” Brawley said to The Cancer Letter.

“It’s a socioeconomic matter. The fact that there are people who are dying who don’t have to die, that makes it a huge issue of moral responsibility.”

The three working groups—part of the NCI Equity and Inclusion Program, overseen by the NCI Equity Council—are:

- Working Group 1: Enhancing Research to Address Cancer Health Disparities

- Working Group 2: Ensuring Diversity of Thought and Background in the Cancer Research Workforce

- Working Group 3: Promoting an Inclusive and Equitable Community at NCI

The tripartite approach promises to “bring meaningful change” to advance research on cancer disparities, develop a diverse cancer workforce and pipeline, and create an NCI that reflects the diversity of the U.S. population.

The NCI Equity Council is co-chaired by Sharpless and Paulette Gray, director of NCI’s Division of Extramural Activities.

These efforts were formed in response to the national awakening on racial justice and health equity issues in 2020—when police brutality and COVID-19 tore through Black communities (The Cancer Letter, May 8, June 5, 2020).

#BlackLivesMatter became a rallying cry that sparked a global movement to dismantle structural racism. On a sweltering summer day last June, amid a deadly pandemic, American healthcare professionals donned their uniforms to kneel in silence and march en masse, carrying placards declaring #WhiteCoats4BlackLives (The Cancer Letter, June 12, 2020).

That momentum continues at NCI, Sharpless said.

“I think across the NCI, there’s just uniform enthusiasm to try and work in these areas, and it really feels like a different moment in time to me,” Sharpless said at the joint meeting.

The lack of representation of Black and Hispanic scientists isn’t unique to NCI—a leadership pipeline survey conducted in 2020 by The Cancer Letter and the Association of American Cancer Institutes found similar disparities across North American academic cancer centers. A recent study of leadership teams at NCI-designated cancer centers by a team of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center researchers reached kindred conclusions (The Cancer Letter, June 25, 2021).

“The [NCI] Office of Cancer Centers is very interested in encouraging diversity in cancer center membership and leadership, and is working on revising the Cancer Center Support Grants to encourage diversity,” said LeeAnn Bailey, co-chair of Working Group 2, and chief of the Integrated Networks Branch at the NCI’s Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities.

Since 2016, NCI has required all cancer centers interested in attaining or maintaining NCI designation to institute community outreach and engagement programs focused on cancer disparities in all aspects of basic, clinical, translational, and population research.

Other noteworthy results stemming from NCI’s analysis include:

- Compared to NIH, NCI has a lower percentage of federal employees who identify as Black. Relative to the civilian labor force, federal employees who identify as Hispanic are underrepresented.

- Across NCI, 19% of staff are employed in administrative positions and 81% of staff are employed in scientific positions. In contrast, 64% of staff who identify as Black are employed in administrative positions, and 36% are employed in scientific positions.

- Relative to white respondents, Black and Hispanic staff responded less favorably to questions about whether NCI’s policies, programs, and supervisors support diversity and inclusion.

- Former Black and Hispanic staff responded less favorably to questions about receiving adequate training to perform their jobs, their positions, making full use of their knowledge, skills, and abilities, and receiving clear guidance on how to advance and excel professionally within NCI.

- Black respondents were less likely to recommend working for NCI to others.

- Only 59% of NCI employees who responded to the 2019 Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey indicated confidence that results would be used to further improve NCI.

“To realize our goals, we must examine how structural racism shapes the state of our institute,” said Paige Green, co-chair of Working Group 3, and chief of the Basic Biobehavioral and Psychological Sciences Branch in the Behavioral Research Program within NCI’s Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences.

What can NCI do—within the limits of its jurisdiction as a research and granting federal entity—to address a disparity that is deeply rooted in structural racism and inequity in American society? That’s the first question asked of NCI leaders after the three presentations.

“How does the NCI circumscribe its investments in what is a horrendous problem that isn’t just about research in health and health equity and disparities?” BSA member Cheryl Willman, director and CEO of University of New Mexico Comprehensive Cancer Center, said at the meeting.

“All of us realize that cancer health disparities aren’t going to be overcome if we don’t deal with economic disparities, socioeconomic disparities, racial justice, and social justice issues,” said Willman, the incoming executive director of Mayo Clinic Cancer Programs and director of Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center (The Cancer Letter, May 17, 2021).

These “upstream precursors” need to be addressed, and NCI can’t do it alone, institute leaders said.

“I do agree that we need to think bigger. Structural racism has always been recognized, but whether or not it’s been prioritized previously is something we’re looking at now,” said Tiffany Wallace, co-chair of Working Group 1, and a program director in the Office of the Director of NCI’s Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities. “You mentioned partnerships, I think that that’s going to be key in trying to address this huge issue.

“I also don’t think I have a solution, but I think we were recognizing the problem and we see what’s ahead,” Wallace said. “And this is what our working groups are strategizing on to figure out more.”

“Immediate actions” presented by each working group include:

- Issue two Requests for Information on enhancing disparities research and increasing workforce diversity; host a stakeholder summit on clinical trials; award postdoctoral fellowships focused on disparities research; increase referral of minority populations to NCI trials; and re-imagine existing NCI initiatives for disparities research.

- Create an Early Investigator Advancement Program that would train 20 young scientists each year to prepare grant applications and complete an R01 grant proposal.

- Share response rates from the 2020 Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey with NCI administrators and on the NCI intranet; improve the Supervisor/PI Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Toolkit and train NCI staff to use it; and launch a trans-NCI speaker series on DEI topics.

“As I hope it was made obvious, by the already implemented immediate actions and the near-term plans, solving these problems is going to be difficult,” Sharpless said. “They’ll require the commitment and new sources, and that has already begun.

“What causes a disparity in a specific disease, it’s always multifactorial and complicated, and there are some things that are more amenable to solution than others. And so, really figuring that out is a big part of the NCI research emphasis here.”

Edited excerpts from the June 14 NCAB-BSA meeting follow:

Ned Sharpless [NCI director]: We started talking about this effort within the NCI probably last fall after events over the summer really caused a groundswell of interest across the NIH, the NCI in really examining the areas where the NCI has the most inequity related to the problems with structural racism.

So, that’s the three groups I described, focusing on your cancer health disparities portfolio on our efforts to develop a diverse workforce. And I’m looking at inclusive NCI culture.

So, we created this administrative structure that I spoke about earlier today and have now been working diligently for months to try and figure out how we can make things better.

I think the work of these working groups and the steering committee has been really wonderful to be a part of this.

I think across the NCI, there’s just uniform enthusiasm to try and work in these areas, and it really feels like a different moment in time to me. We’ve done some communicating about the effort internally, but we wanted to get it to an advanced stage before we showed some of the progress and future plans to the joint boards today.

So, we are now going to have three presentations and the first is going to be given by Tiffany Wallace, who is one of the co-chairs of the Cancer Health Disparities Working Group.

Working Group 1: Enhancing Research to Address Cancer Health Disparities

Tiffany Wallace [program director, Office of the Director, Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities, NCI]: I am a co-chair for working group 1, which is the working group that is focused on Enhancing Research to Address Cancer Health Disparities. And today I’ll be presenting on behalf of the other working group co-chairs, specifically Dr. James Doroshow and Dr. Worta McCaskill-Stevens.

So, the overall purpose and the charge for our working group is really to develop and to prioritize research recommendations that will help us to better determine what the upstream precursors are to cancer disparities, and then to furthermore implement those research programs to ultimately eliminate disparities and promote health equity.

To do this, we propose to facilitate, in many cases, implemented research activities that will help us develop initiatives focused on advancing prevention, interventions, and implementation.

We are focused very broadly across the entire cancer continuum, and we’re interested in advancing everything from prevention through treatment and survivorship. And members of our working group are of diverse expertise and we’re focused on research including basic and translational all the way through to population sciences and treatment.

Now, if you’re following along with the UNITE Initiative, our working group most aligns with the N Committee (New research on health disparities, minority health, and health equity), which is also focused on disparities and health equity, and we’re working to stay connected with them and coordinate. We want to avoid any redundancy in our efforts and, if possible, find points for synergy.

So, this is a very broad overview of what our goals and activities are as a working group. I’ll take a broad approach at this, but then we’ll talk a little bit more on specifics on how we’re approaching these goals in our following sides.

In general, our first goal is really to take a little bit of a step back and do a landscape analysis of the field, and then identify some key diverse stakeholders to get input. And we anticipate that by doing this, we’re going to better be able to understand where the current gaps are, where the opportunities are for research and help to define our overall priorities.

Our second goal is really to take that input and then develop and prioritize our research recommendations. And we anticipate that a lot of the input for this will come from our landscape analysis and stakeholders, but also from the members of our working group and those at NCI. And then our third goal will be to take those recommendations and to promote and implement those activities.

One of the first things that we did as a working group was to come together and identify some immediate actions. We understand that a lot of the work that we are charged with doing is going to take some significant time and effort. But we wanted to get to work right away and identify some things we could do now.

One of the first things that we did was publish requests for information seeking stakeholder input. So, we currently have two RFIs out, the first focused on how to better enhance cancer disparities research. And the second one is more aligned with our working group 2, which you’ll hear from in just a minute, trying to seek ways to improve workforce diversity. So, these are currently out, we encourage you to take a look if you have a response to please submit it.

As a note, these RFIs are distinct to NCI. So, even if you submitted a response to the UNITE Initiatives call just a few months ago, we encourage you to consider submitting a response to us as we are staying connected and avoid any redundancy.

Another activity we are involved in is developing a summit with multi-stakeholders that’s focused on ways to better increase inclusion and equity in cancer clinical research and clinical trials. I don’t have too many details to share today as we’re very much still in the planning phase, but we do anticipate that there may be a virtual or a hybrid event possibly later in the year.

In addition to being focused on advancing research throughout the extramural research community, we’re also interested, looking internally here at NCI within the Intramural Research Program. We want to see if we can expand the amount of cancer disparities on minority health and health equity research that’s ongoing here.

So, we teamed up with the center for cancer research, CCR, the division of cancer epidemiology and genetics, DCEG, and a trans-NCI activities committee called CDAC—the Cancer Disparities Activities Committee—to develop some training awards. And so, we had both post-doctoral fellowships as well as research project awards for one to two year projects.

Again, it’s the hope that this will expand the amount of research ongoing here within NCI intramural program. Next week, we teamed up with a trans-NCI working group that’s been working on a concept for quite some time.

This is led by CRCHD (Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities). I’m not going to talk too much about it, because you’re actually going to be hearing from Dr. LeeAnn Bailey tomorrow as she presents this concept. But it’s called connecting underrepresented populations to clinical trials. And the purpose is really focused on outreach and education interventions that are designed to help increase referrals, accrual and retention, hopefully of underrepresented populations into NCI clinical trials.

Lastly, we know that there’s a lot of activities ongoing at NCI currently that have been pretty successful in advancing disparities research. And so, we proposed to identify some of those, if they’re ending, reissue them, perhaps even re-imagine them in some cases. And so we’re currently in the process of doing that.

I’ll take the final few slides just to review some of our ongoing and future activities. As I mentioned, we’re interested in doing a landscape analysis and this is underway. I want to make a comment that this is not a comprehensive analysis, but instead we’re focusing in on some key publications on different topics, all related to disparities, and all of which provided recommendations for how to move the field forward and looking to see what overlaps and what’s unique and what might inform our priorities and agenda.

I also wanted to make the point that this is not a portfolio analysis of funded NCI research. Those efforts are being done elsewhere within NCI as well as part of the NIH’s UNITE committee activities. And we’re staying with that.

As far as the research activities, some examples of what we’re working on now includes teaming up with the Division of Cancer Prevention, working with the Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis to conduct a survey and an analysis looking at how telemedicine is being used in NCI clinical trials, particularly both before and after COVID-19.

We all know that telemedicine usage has increased and changed in response to this pandemic. And we’re interested in seeing what were some lessons learned and how telemedicine may be useful and advancing health equity in cancer clinical trials.

Next, we are working with the Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences here at NCI to further advance research and cancer control, particularly in persistent poverty areas where we recently released a notice soliciting PO1 applications.

If you’re not familiar with persistent poverty areas, the definition for persistent poverty area is a county that has poverty area rates that are 20% or more in the U.S. Census data from 1980, 1990 and 2000.

And it’s well-documented that individuals facing persistent poverty have worse cancer burden, worse mortality and morbidity. Currently, the current classes or characterization, this is data from the USDA, includes that over 10% of U.S. counties are considered persistent poverty areas.

You can see the map here. Most of these fall within the rural south. Now, importantly, we’re working further with the USDA to expand this definition, to get a little bit more granular than the county level and use the census tract-level data. And when we do that, I don’t have that data here today, but it does seem that each of the 50 states, including Washington, D.C., has consistent poverty areas.

So, we’ve been working, the DCCPS has had a number of supplement programs. The first was targeting R01 grants, that was in 2020. Six awards were made through that call.

There was another supplement program this year targeting P30 Cancer Center Support Grants, again, designed to advance research in persistent poverty. Those awards are still pending possibly in September. And as I mentioned now, we have the P01 solicitation, that’s out.

Again, hoping to attract these larger multidisciplinary teams doing collaborative research to really address the burden of individuals in persistent poverty areas, by advancing prevention and cancer delivery strategies.

So, looking at it, as I mentioned, we are coordinating and synergizing across the NCI and NIH. I’ve mentioned our connection to the N Committee of the UNITE. We’re also working with an ongoing activities committee within NCI, called the Cancer Disparities Activities Committee.

We’re also seeking solicitation from NCI for innovative ideas, as well as the extramural community. Right now, if you have anything to share, we think the best way to do that is to submit a response to the RFIs that are out.

To end, I wanted to just briefly introduce you to the other working group members from working group 1. As you can see, there’s a lot of expertise spanning all of the divisions offices and centers at NCI. They’re very passionate and motivated to address disparities, and we want to thank them for their efforts up till now, and look forward to moving ahead in the future.

Sharpless: Thank you, Tiffany. Her presentation reminded me; I wanted to make a point that I’ve asked all the speakers to talk about how the NCI effort relates to the greater NIH initiative called UNITE.

Some of these problems are trans-NIH problems; some are better solved at the NCI. So, we work closely with that effort. Next, I think we have Dr. LeeAnn Bailey from CRCHD talking about the working group 2 efforts.

Working Group 2: Ensuring Diversity of Thought and Background in the Cancer Research Workforce

LeeAnn Bailey [chief, Integrated Networks Branch, Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities, NCI]: We are delighted to be participating in this joint board meeting and to share some of the activities of working group 2 or Ensuring Diversity of Thought and Background in the Cancer Research Workforce. My name is LeeAnn Bailey, and I will be presenting today on behalf of our work group and my fellow co-chairs Drs. Glenn Merlino and Susan McCarthy.

Our working group is focused on enhancing NCI’s efforts to develop a diverse and balanced cancer workforce, both intramurally and extramurally. Our efforts will focus on enhancing the current research and training levels, training efforts at all levels to not only retain, but also sustain a viable and diverse workforce.

We’re also interested in new approaches to support and sustain the equal representation of underrepresented groups throughout the research training pipeline. As was previously alluded to, there’s a larger effort called UNITE at NIH, and we are working with Subcommittee E of this effort, and it’s focused on the extramural research ecosystem. Their activities consist of a larger effort specifically to change policy, culture, and structure to promote workforce diversity across NIH.

Our work group has several goals to not only devise, but implement strategies to sustain the gains that have been made, but also to increase the number of investigators from underrepresented groups in cancer research at all the levels, from early training to leadership positions.

Specifically, one of the key gaps or challenges that our group focuses on is the lack of the number of application awards for underrepresented groups. This challenge has been longstanding and it’s been documented by [Donna] Ginther, [Richard] Nakamura and others, but there are significant differences in award probability based on race and ethnicity.

As a matter of fact, just last week, you might’ve seen a recent commentary that was published in Cell by [NIH Director] Dr. [Francis] Collins and colleagues that further emphasizes the disparity in NIH R01 funding for grant application and funding rates among these groups.

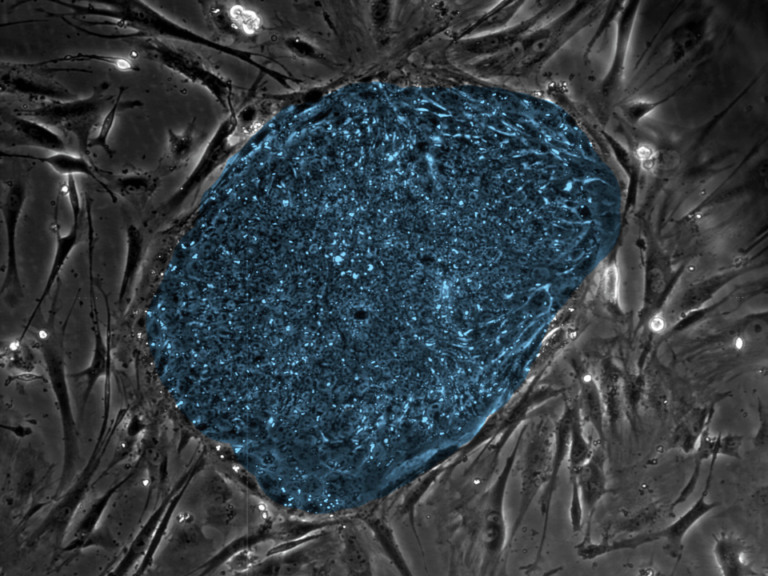

Diversity in the R01 pool has been a substantial challenge at NIH and NCI for many years. It’s not going to be easy to overcome, nor is it straightforward. The underrepresented group R01 problem is an old and intractable problem that NCI is taking active steps to tackle. We can see the demographics of the NCI’s FY20, NCI R01 applicants in the top row and the awardees in the bottom row.

This data highlights two challenges, the top row concerns the applicant number. As you can see, there is substantial opportunity and need to increase the application number from underrepresented groups, such as Black or African Americans and Hispanic Latinos. The bottom row addresses the funding gap for these underrepresented groups, which leads to a lower representation in NCI awardees compared to the overall applicant pool.

So, there are multiple underrepresented groups among the NCI R01 principal investigator pool, including Black and African Americans, Hispanic Latinos, American Indian, or Alaskan Native and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander. These challenges have persisted over time.

We’ve had one of the most dramatic examples here in that the percentage of Black or African American awardees has remained stable at 1% over the last decade. The funding gap is especially apparent for this demographic. And again, we really understand that this R01 funding challenge is a global problem for NIH and NCI. There are numerous efforts that are ongoing at NCI and working group 2 seeks to address this problem with a new program.

So, we understand that this is a very large problem. And in order to begin to address this challenge, we have proposed a small but significant step to promote the transition of extramural and intramural early career investigators to independent investigators. And it’s one of our immediate actions.

It’s titled the Early Investigator Advancement Program. The program consists of monthly webinars for education and engagement, grant application preparation and technical assistance, as well as the connection and linkage to mentors and the expansion of professional networks. It also includes a virtual hub for communication and resources, and where possible, we would like to be able to make the resources available to the public.

The outcomes for each participant are listed and include the completion of an R01 grant proposal by the end of the program. And also again, becoming a larger part of a cadre of peers with similar career goals, the engagement with mentors, as well as the development and understanding and awareness of what fellows are currently available.

This is going to be a program that’s going to encompass about 20 participants per cohort, and we anticipate one cohort per year.

Our ongoing efforts include, again, collaborating with UNITE and it consists of webinars, summit and meeting planning. UNITE is addressing a broader scope that encompasses topics like peer review, program engagement, as well as a variety of other factors. We intend to be tightly connected to the other working groups, especially work group 4, for metrics and evaluation.

So, in addition to the Early Investigator Advancement Program, working group 2 is developing the next set of activities and programs for review by the Equity Council—one of which is currently in development is the consideration of perhaps a diversity R01.

We really do want to hear from you, NCI and the larger cancer research community. The group wants to hear about and identify other models and efforts that are ongoing across NIH and perhaps at your institution, as well as the community, so as to not reinvent the wheel, but to augment activities and increase impact.

For example, you just heard about the request for information that was issued by work group 1 about workforce diversity and cancer health disparities research. We sincerely hope that you will participate and respond because we all need to work together.

There are some exciting efforts that have been launched recently. I’d like to touch briefly on the first program or the first initiative, it’s the Faculty Institutional Recruitment for Sustainable Transformation Program (FIRST).

And this is a transparency NIH program that’s supported by the Common Fund that aims to enhance and maintain cultures of inclusive excellence in the biomedical research community. Inclusive excellence refers to cultures that establish and sustain scientific environments that cultivate and benefit from a wide range of talent.

The program also seeks to have a positive impact on faculty development, retention, progression, and eventual promotion, as well as the development of inclusive environments that are sustainable. There’s been substantial NCI involvement and leadership in the development of this initiative and we are very much looking forward to the outcomes.

At NCI, leadership is examining activities that reflect diversity of thought with regard to how it is we might increase diversity across the Institute.

There are efforts that are ongoing, such as the R21 being reissued, and it’s a continuation of an NCI program to enhance the diversity of the pool of the cancer research workforce by recruiting and supporting eligible investigators from groups that are underrepresented. It bridges investigators who have completed their research training and may need just a little bit of extra time to develop a larger research project grant application.

Select pay, NCI has always had procedures in place to select grants to pay out of rank order. NCI uses a holistic approach based on a variety of considerations when deciding whether to award select pay.

What is new is the examination of the current language with the intent to refine and clarify the policy, the Specialist Programs of Research Excellence or SPORE programs have funds available for development research project awardees from underrepresented groups. It’s an extra $25,000 in direct costs per year that can be requested for a developmental research project that’s led by an investigator from the aforementioned groups.

And then lastly, the Office of Cancer Centers is very interested in encouraging diversity in cancer center membership and leadership, and is working on revising the Cancer Center Support Grants to encourage diversity.

And lastly, in summary, this slide displays the work group 2 members and their representation across NCI. They are truly a talented, committed and passionate group of folks that are tirelessly advancing this effort. And we’d like to thank them for their service and contributions today.

Working Group 3: Promoting an Inclusive and Equitable Community at NCI

Paige Green [chief, Basic Biobehavioral and Psychological Sciences Branch, Behavioral Research Program, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, NCI]: I’m honored to serve as co-chair with Shannon Bell and Satish Gopal of the Promoting an Inclusive and Equitable Community at NCI working group. Now, we are the third working group in the NCI equity and inclusion program. I will focus on our institute’s internal efforts to establish and sustain cultures of inclusive excellence within NCI.

So, within the walls of our institute, we seek to build and sustain scientific and administrative cultures of excellence that are inclusive, equitable, supportive, and reflective of the diversity of the U.S. population.

Now, broadening our inclusion engagement and valuation of diversity—arising from lived experience and social identity—promises to positively impact our service as the federal government’s principal agency for cancer research, training and information dissemination activities within the United States and globally.

Thus, our working group strives to enhance the diversity of our internal scientific and administrative workforces through the recruitment, retention, recognition, and promotion of individuals from otherwise underrepresented and marginalized groups.

Our working group goals are to assess our internal diversity, equity, and inclusion landscape using available qualitative and quantitative data, engage NCI leaders, staff, and advisors, and social and organizational change processes that are safe, productive, and accountable, and use those processes to identify and implement recommendations that will create an internal structure and culture that thrive on diversity, equity, and inclusion excellence—which is achieved through a transparent, accountable, and sustained commitment to realizing that ideal.

To realize our goals, we must examine how structural racism shapes the state of our institute.

Our working group has identified, collected, and analyzed available workforce and workplace experience data. Our initial analyses have focused on our internal full-time equivalent workforce due to available data resources. However, we acknowledge the need to understand the experiences of our contractors and our training fellows similarly, and we’re working to identify appropriate data sources.

Now, I will share highlights from the analysis of data obtained and synthesized from the NIH Office of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion, the NIH Scientific Workforce Diversity Office, the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey and the NIH Exit Survey.

To promote awareness, transparency, accountability, and engagement with our internal community, we presented the snapshot at the June 3 NCI town hall, and we plan to share updated results NCI-wide later in the summer. Now, to orient you to our results and for the sake of time, when referring to Black and African American and Hispanic, Latinx groups, I will use the terms Black and Hispanic respectively.

We begin by observing that the distribution of NCI’s internal workforce differs from NIH’s internal workforce and the broader U.S. civilian labor force. Among our federal employee workforce, 3% identify as Hispanic, 13% identify as Black, 25% identify as Asian and 58% identify as white.

So, compared to NIH, NCI has a lower percentage of federal employees who identify as Black and a higher percentage of federal employees who identify as Asian. Relative to the civilian labor force, federal employees who identify as Hispanic are underrepresented and federal employees who identify as Asian are overrepresented at NCI.

Of note, representation of scientists that identify as Black or Hispanic is strikingly low for senior positions within our intramural research program. As shown on the slide, 2% or less of senior scientists, clinicians, or investigators within the NCI Intramural Research Program identify as Black or Hispanic.

Now, this slide focuses on approximately two-thirds of the NCI workforce employed in the five most common administrative and scientific positions. Here we observed that the distribution for Black staff across administrative and scientific positions is different from the NCI workforce distribution overall, in which 19% of staff is employed in administrative positions and 81% of staff is employed in scientific positions. In contrast, 64% of staff who identify as Black are employed in administrative positions, and 36% are employed in scientific positions.

Moreover, although not reflected on this data slide, we observed distribution disparities by pay grade for Black staff, relative to NCI’s internal workforce.

These data are from the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey administered annually to federal government employees by the U.S. Office of Personnel Management. The survey measures workplace perceptions and employee engagement and motivation. Responses 65% and higher are considered positive.

Now, in 2018 and 2019, we observed that employees perceive NCI positively overall. However, relative to white respondents, Black and Hispanic staff responded less favorably to questions about whether NCI’s policies, programs, and supervisors support diversity and inclusion.

Finally, the experience of a different NCI climate appears to extend to those who choose to leave NCI. Among NCI staff who completed the NIH exit survey between 2018 and early 2021, former Black and Hispanic staff responded less favorably to questions about receiving adequate training to perform their jobs, their positions, making full use of their knowledge, skills, and abilities, and receiving clear guidance on how to advance and excel professionally within NCI.

Furthermore, Black respondents were less likely to recommend working for NCI to others.

So, against the background of today’s reckoning with our nation’s history of structural racism, an opportunity emerges to create diverse, equitable and inclusive cultures of excellence. Our success will broaden our capacity to lead, conduct, and support the cancer research enterprise.

As you can see, Dr. Collins and Dr. Sharpless are committed to diversity, equity, and inclusion paradigm shifts within our scientific and administrative workforces and biomedical research overall. We, the working group, commit to working with NIH and NCI leaders, staff, and advisors to realize and sustain the change we want to see within NCI and the cancer research enterprise. We are charged to lead on behalf of our nation.

So, where do we begin? In addition to the inward-facing landscape analysis, we’ve received support to implement a few additional immediate actions. Please note that these are initial actions—considerably more substantive work is needed to build a diverse community with inclusive and equitable social norms at NCI.

Agencies use the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey results to build on strengths and improve challenge areas. So, relative to NIH, NCI employees consistently report higher positive perceptions of their leadership, their intrinsic work experience, their environment, and the opportunities to contribute to our mission. This is great news.

However, only 59% of respondents indicated confidence that results would be used to further improve NCI.

To address this concern, we are expanding the transparency of results by posting response rates for each NCI work unit with at least 10 respondents. And we’re posting that to the NCI intranet and then also disseminating work unit-specific results to NCI supervisors and managers.

This year, supervisors and managers must share, discuss, and act upon results with their staff, and implementation support is available through our Office of Workforce Planning and Development, which is directed by our working group co-chair Shannon Bell. For the first time this year, we will examine and share survey results by available demographic characteristics.

This is a significant development and it will help us further understand staff perceptions, motivations, and engagement by crude measures of social identity. We anticipate posting that additional data to our intranet by the summer.

We have refined and we’ll pilot a new Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Toolkit for NCI supervisors and intramural research program investigators this summer. The toolkit was created to improve supervisor and staff awareness of diversity, equity, and inclusion expectations and to support dialogue on bias, exclusion, and racism in the biomedical research field.

The toolkit is evidence-informed and closely aligned with NIH’s Office of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion resources. The first training for NCI’s facilitators will occur this month and we will pilot the toolkit with NCI supervisors, principal investigators, and staff this summer.

On June 9, we launched the Trans-NCI Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Speaker Series. This endeavor compliments the toolkit by bringing notable diversity, equity, and inclusion organizational change experts to NCI to share their perspectives with leaders and staff. The NCI community is encouraged to attend those lectures, participate in the extended question-and-answer discussion periods, and most importantly, to nominate speakers to the series.

So, moving forward, we will partner with our leadership staff and advisors to identify, implement, and evaluate short and long-term strategies to achieve transparent, accountable, and sustainable structural and cultural change within NCI.

Community investment and engagement are critical, and we encourage any member of our community to submit feedback, ideas, concerns, and questions by email and during upcoming division office or center events.

Today, I provided just brief highlights of our initial landscape analysis. However, updated results with deeper explanations will be presented by webinar this summer to our internal community.

And we will host listening, question, and engagement sessions focused on the analysis and how the results can inform our efforts to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion within our internal community.

Secondly, we will leverage activities and resources of extant NCI communities, such as the Diversity Task Force and the Workplace Civility committees. Moreover, we welcome the opportunity to learn of and leverage best practices arising from your efforts to enhance diversity, equity, and inclusion outcomes within the scientific and administrative workforces at your institution.

We will coordinate with UNITE and implement recommendations to build organizational structures, systems, and policies that create and sustain normative cultures of diversity, equity, and inclusion excellence within NCI and NIH and the larger scientific communities.

To close, we offer our vision for an inclusive and equitable internal NCI community. It is an NCI where all employees value diversity, equity, and inclusion as guiding principles. It is an NCI where all employees practice a culture that fosters diversity, equity, and inclusion with authentic intention, resulting in sustainable progress towards accountable yet aspirational benchmarks. And it is an NCI where all employees are engaged, respected, valued, and recognized equitably for their contributions to our mission.

So, on behalf of NCI leadership, I conclude by thanking the dedicated members of our working group. They have provided remarkable vision, leadership, and support for the work shared with you today.

Our liaison with NIH efforts to eliminate organizational structures, systems, and policies that perpetuate exclusion and inequity based on race is facilitated through four of our members doing double duty as UNITE committee members.

Sharpless: I want to thank all three speakers for their terrific presentations. I also want to thank the other working groups too, they did a lot of work on this, and you can see it’s a large number of individuals on these various working groups. It’s really a trans-NCI effort.

Also, as I mentioned earlier this afternoon, there were two other working groups. There’s working group 4, which is a Systemic Tracking and Evaluation [of Equity Activities] working group co-chaired by Doug Lowy and Michelle Bennett, and then working group 5, which is Communications Outreach for Equity Activities.

That’s co-chaired by Peter Garrett, Angela Jones, and Anita Linde. I did not ask them to give presentations today in the interest of time, but their work is to support the entire effort across the NCI with important things like metrics and tracking of our efforts, as well as communicating our efforts.

The other point I’d like to make before we take some questions is, as I hope it was made obvious, by the already implemented immediate actions and the near-term plans, solving these problems is going to be difficult. They’ll require the commitment and new sources, and that has already begun.

So, we have really realized that it’s not enough to just talk about these problems, but we will actually have to use funds and use our authorities to try and address them. And I hope that is clear in the presentations thus far. And I’d be happy to talk more about that specifically if there are questions.

NCI advisors respond

Cheryl Willman [director and CEO, University of New Mexico Comprehensive Cancer Center]: Dr. Wallace, Dr. Bailey, Dr. Paige, your presentations were outstanding. And Ned, I just want to congratulate you for taking these issues so seriously. I know that the NCI has really done that increasingly over the years, and I think these presentations were really thoughtful.

So, my question perhaps is best directed to Dr. Wallace and Dr. Bailey and it’s a little unfair, but several members of the BSA and NCAB are sitting on an [American Association for Cancer Research] task force that are writing the 2022 State of the Nation and Cancer Health Disparities.

Ned, we’ll want to interact with you and a lot of your team for data and comments, as you know, and several of us are on AACR, some disparities and DEI task forces as well. And we had very long meetings last week, and we came to a challenging discussion point, which is:

How does the NCI circumscribe its investments in what is a horrendous problem that isn’t just about research in health and health equity and disparities? All of us realize that cancer health disparities aren’t going to be overcome if we don’t deal with economic disparities, socioeconomic disparities, racial justice, and social justice issues.

So, this problem becomes so consuming that it almost seems, how can we actually have an endpoint? And so what I want to get at is, how do we think about that when we structure grants?

The example I gave was, tribal health disparities, where the Indian Health Service has a $6 billion budget, but their budget probably should be $40 billion. If they really met the need where, Pueblo homes and Navajo homes, 30% don’t have drinking water and electricity. These are such fundamental social and economic disparities that they set a bar to achieve health equity so high that it’s hard to overcome.

And so, what we were struggling with, Ned, Tiffany, and LeeAnn, in that report is, how do we put the context of the research we want to do at the NCI, where the mission we want to address at AACR in the context of these massive, much larger disparities that probably are going to be hard to impact through grants we might do with you.

So, what we got to talking about, are there ways we partner with other agencies? Are there ways that we do advocacy to try to deal with these challenges in parallel?

Again, I said, that’s a bit of an unfair question, but I think it framed how tough the discussion was for us Ned, to figure out how we draw that circle.

Sharpless: These are obviously really challenging issues and I thought you summarized the problem and in our thinking on this area really well. Obviously, the budget of the NCI doesn’t allow us to fix some of these societal problems that are much larger than any single federal agency could to take on.

I think our real work here, we feel, is to understand these: Cancer disparities always turn out to be so interesting. When you really look at those, what causes a disparity in a specific disease, it’s always multifactorial and complicated, and there are some things that are more amenable to solution than others. And so, really figuring that out is a big part of the NCI research emphasis here.

So, I will let Dr. Wallace try to explain to you how we think about cancer health disparities in this larger context. I think also it would be good to have LeeAnn Bailey weigh in as well, because part of this is a workforce issue. We want to develop a scientific workforce that reflects the American public.

Wallace: Sure. I mean, I don’t know if I have an answer because it is a complicated question. But I do agree that we need to think bigger. We can’t think about addressing disparities in the same way that perhaps we’ve thought about previously.

We need to think multidisciplinary approaches. We need to think beyond traditional thoughts, look at more upstream precursors that maybe we haven’t focused on enough in the past.

Structural racism has always been recognized, but whether or not it’s been prioritized previously is something we’re looking at now. You mentioned partnerships, I think that that’s going to be key in trying to address this huge issue.

So, I also don’t think I have a solution, but I think we were recognizing the problem and we see what’s ahead. And this is what our working groups are strategizing on to figure out more. So we’ll think about it more. And if we do come up with some more substantial answers for you, Cheryl, certainly we’ll reach out.

Bailey: What I can speak to is the fact that, in order for us to address cancer health disparities, and increase workforce diversity, specifically from underrepresented groups, we really have to take action now to train the next generation of competitive researchers in cancer and cancer health disparities research. But they go hand in hand.

And so, given the fact that science is very much multidisciplinary and requires a variety of contributions from different sources and people, we really want to try to coalesce and work together to be able to address these items now. There’s been a lot of historical challenges, structural racism, impediments over time.

It’s deplorable the fact that 1% of R01 funding for African Americans over 10 years is acceptable; right? And so, I think working together, it will require the engagement of variety of different groups, not just academic, but also community-based participatory research and clinical care.

I think we just really need to be realistic and tackle it and try to understand the disparities to figure out how to address it.

Otis Brawley [Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Oncology and Epidemiology, The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins University]: I just want to remind everybody that the biggest reason for the disparities really goes back to something that was mentioned earlier, and that is, a substantial number of people don’t get the prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment in high quality that all Americans should get.

The other thing that we developed when I was at the American Cancer Society is, ironically, the largest disparate population in terms of people, because folks don’t get adequate care, are white Americans. It’s not really a race issue as much as it is a socioeconomic issue.

And the NCI, I think, has been very good at doing work to say what I just said is true. I don’t know if that work has been publicized as much as it could be. And there have been times when it probably was not a good idea to publicize it, to be honest with you.

Sharpless: I want to make a point that the NCI has been working on this area for a long time, and we have a very substantial portfolio in cancer disparities that I’m really proud of.

It is probably worth mentioning that this may be one of Dr. Croyle’s last joint board meetings and Bob Croyle has been a real innovator and thinker about this for a long time. And given that we might not have an opportunity to recognize Bob, which in the future, we should point it out that it’s really thoughtful things that he’s been recommending to NCI for a long time.

But that doesn’t mean it’s not a fair question to say, what could we do differently or better or in addition, and certainly, these broad problems still persist. And so I think that it’s tough.

Electra Paskett [director, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, The Ohio State University]: I really want to thank all the presenters. Those were really stellar presentations and really exciting initiatives. And thank you, Dr. Sharpless for directing this so well.

I just want to make a comment Dr. Wallace, I hope that you’re aware that the NCAB subcommittee, the Ad Hoc Subcommittee on Population Science, Epidemiology, and Disparities is going to convene an ad hoc working group that is going to advise on strategic approaches and opportunities for research on cancer among racial and ethnic minorities and underserved populations across the continuum.

And I believe that this ad hoc working group can work very closely with your group to identify the areas where there are holes for research in various minority and underserved populations.

Wallace: Thank you, Dr. Paskett. Yes, we are aware we are staying connected and actually Dr. [Phil] Castle, who will be a great liaison between the two efforts is a member of our working group, as well as leading the NCI’s efforts there. So, thank you for pointing that out and they are aware and we definitely will be staying informed.

Kevin Shannon [Auerback Distinguished Professor of Molecular Oncology, professor, Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco]: I just had a comment on Dr. Bailey’s excellent presentation. And that is, I think many of us who have thought about these issues and have been trying to work on them in different extramural locations have noticed that the attrition from the pipeline—which I’ve talked about before with respect to women and MD PhDs and physician scientists—but this is even worse for diverse young investigators.

And so I would really encourage your office to go back, back, back, back to medical school to MSTPs (Medical Scientist Training Programs), to T32s. Trying to get early stage investigators to write R01s is great, but you need to get them to the place where they can write an R01.

And there just aren’t very many people in the K0A pool or in a similar pools, the K99, R00 pool. And I would for sure, really try to look at the K0A, R00, K99, the T32s, the MSTPs, the NCI one-year program for undergrads. We just got to get more people into the pipeline or earlier and then try to keep them there.

It’s important that NCI is doing this because NCI has, in my mind, always been progressive in this area and has always been a leader—and has the opportunity to lead, not only in oncology, but also in medicine right now.

Otis Brawley

I just think that if we limit this to people who are in that transition where they’re ready to write an R01, we’ve lost the war already, we just don’t have enough people who are getting to that place.

Bailey: Thank you so much for that insightful comment. And actually the Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities has the CURE (Continuing Umbrella of Research Experiences) program, which is the continuing umbrella of research experiences.

And we actually offer support for students, believe it or not, as early as middle school now, with our Youth Enjoy Science [Research Education] Program all the way up until their first faculty appointment. So, these are all competitive independent opportunities.

It really supports a continuous career development, as well as focusing in on some of the areas that’s touched upon. I would really encourage everyone to have a look to see how it is. The center is supporting diversity with that regard, but we also have institutional opportunities as well.

So, we appreciate that, and we are understanding that it’s critical to reach these students in the early part of the pipeline.

Shannon: I mean, one thing you might consider is sending some notifications out to the cancer centers, to the SPORE directors, that we really are interested in funding graduate-level students, early-stage investigators, clinicians, medical students, and we’re ready to get money out the door to help African Americans and Hispanic and other underrepresented people in the pipeline. I think it’s going to be a good investment.

Just as an anecdote quickly in our SPORE, we really should spend some of this money on people in training. And of course the SPORE program, we can’t use developmental funds for somebody who doesn’t have a faculty appointment. So, our hands are tied. We want to do something, we can’t do it because of the rules.

Peter Adamson [global head, Oncology Development and Pediatric Innovation, Sanofi]: I think the data that was presented are both shocking and totally unsurprising. And I want to build a little bit on what Cheryl said. At this year’s ASCO, Lori Pierce and her presidential address—I think one most impactful presidential addresses I’ve heard in many years—it focused on institutional racism, her own journey, as well as the founding member of ASCO Jane Wright. And if you haven’t seen it, I would encourage everyone to listen to it.

My question is this, are these efforts moved forward? You heard from Cheryl and AACR, their efforts at ASCO, there a lot of people appropriately beginning to devote major energy for this.

As you move forward, I think efforts to reach out to the other organizations—to see really who’s going to be in the best position to take on what is going to be a multi-dimensional problem—would be helpful. I know it’s not easy.

We’re still very much at the beginning of this, but I certainly applaud the efforts you’re taking within NCI and encourage additional outreach, because the problem is obviously quite widespread.

Sharpless: I think the point is well taken that partnership will be key. There are certain restrictions on what the NCI can do. Dr. Croyle has some in the chat box, along those lines pointing out that there’s been some challenges in the past.

But what I think has been very encouraging is that we have all these digital partners coming to us saying, “We want to do something.” I mean, there’s this real sense with many of the large advocacy organizations, not the research organizations that we work with, that the time is now to do something. We appreciate the comment.

Victoria Seewaldt [Ruth Ziegler Professor, chair, Department of Population Sciences, Beckman Research Institute, City of Hope]: I want to go and echo LeeAnn’s comments about the success of the CURE program. I’ve been a mentor for many successful CURE investigators. One thing I want to point out as a practical thing is that we have a huge disparity in the ability to write, and undergraduate education and graduate education does not remedy this, neither does medical school.

And so, the problem is that investigators, underserved investigators are having to go write grants without the necessary tools. I think one effort should be invested in developing more creative writing strategies to teach new investigators, particularly underserved investigators, how to write.

We’ve done this. And I’ve been very successful in getting our new investigators R01 funding, but you have to use non-traditional approaches. And I think that there should be investment in this.

Francis Ali-Osman [Margaret Harris and David Silverman Distinguished Professor of Neuro-Oncology, professor emeritus of neurosurgery, Duke University Medical Center]: I just want to echo what Kevin said, for many, many years, trying to deal with this problem. I think the pipeline is really, really critical and my time at MD Anderson in Houston and now at Duke, there are several, outstanding minority institutions, but there is really no mechanism or incentive actually to engage—Ned’s time in Chapel Hill, I’m sure, Ned, you have your own experiences.

But I think one way to improve the pipeline is really to incentivize, either by mandate or by resources, to make sure that these two groups really crosstalk and actually have a pipeline that allows some talented students who are interested in cancer or in science in general, to gain from experience of these other major institutions.

I think we’ve been talking about this in our SPORE, in our cancer center when I was associate director. But really coming out with concrete plans that allows these two to crosstalk and establish that pipeline, I think has been something that’s been lacking. It would be great.

The CURE program is great, but I think locally there’s a lot that can be done that really is not being done.

This story is part of a reporting fellowship on health care performance sponsored by the Association of Health Care Journalists and supported by The Commonwealth Fund.