Since March 2018, P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now), an organization founded in 2017 by photographer Nan Goldin, has held demonstrations at art museums in New York, Washington, DC, Boston, London and Paris to protest their acceptance of money from the Sackler family, owners of Purdue Pharma, a company that been accused of fomenting the prescription opioid addiction crisis.

More than 200,000 deaths attributed to prescription opioid overdoses have been reported since the company’s introduction of the narcotic medication OxyContin in 1995. More than 47,000 prescription opioid deaths are predicted to occur in the U.S. in 2019.

Yet this horrific toll represents less than a tenth of the number of deaths from cancer, heart disease, and emphysema in the U.S. each year due to cigarette smoking. And in contrast to the caustic criticism directed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Guggenheim, the Freer-Sackler Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution, and others for cozying up to the Sackler family, the arts community has remained silent for more than 50 years when it comes to the solicitation by these very same bastions of culture of tens of millions of dollars from the nation’s largest cigarette manufacturer, Philip Morris, maker of the world’s top-selling brand, Marlboro.

The New York Times reported on May 15 that the Sackler family trust has donated more than $80 million to arts and sciences since 2010. Mother Jones reported on March 23 that the Guggenheim accepted at least $6.4 million from the Sackler family between 2001 and 2017.

On P.A.I.N.’s webpage, the group declares, “We’re committed to holding the manufacturers of the opioid crisis and speaking for the hundreds of thousands of voices that have been silenced by the epidemic.” P.A.I.N.’s manifesto includes the following:

“The Sacklers have ignited the largest public health crisis in American history. They must be held accountable for the harm they’ve done and are now attempting to unleash on a global scale.

“We demand that all museums, universities and institutions worldwide publicly refuse future funding from the Sackler family.

“We demand that all museums, universities and institutions worldwide remove their Sackler signage.

“We demand an immediate response from the museums and institutions that bear the Sackler name. To remain silent is to be complicit.

“We thank the museums and institutions that have cut ties with Sackler funding and urge all cultural institutions to follow their example and to divest from dirty money.”

Wrongly tarred with the same brush?

Goldin’s and P.A.I.N.’s crusade to end the acceptance of ill-gotten gains from the sale of prescription opioids seems well-intentioned. The toll taken by these drugs is tragic.

Ironically, on P.A.I.N.’s webpage, a photograph of Nan Goldin smoking a cigarette accompanies her account of having undergone treatment for addiction to OxyContin.

Moreover, as Wall Street Journal arts critic Terry Teachout observed in a Feb. 27 column “Museums and Shaming,” P.A.I.N.’s take-no-prisoners targeting of the Sackler family includes the philanthropy of the late Arthur Sackler, MD, who was not connected to OxyContin, which was introduced nearly a decade after his death in 1987.

Thus, the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of the Smithsonian and the Sackler Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, sites of P.A.I.N. protests, were not funded by prescription opioid money.

Goldin would argue that Sackler’s development of marketing strategies aimed at prescribers of the tranquilizers Valium and Librium beginning in the 1950s, as described by reporter Patrick Raddon Keefe in the New Yorker in 2017 (“The Family that Built an Empire of Pain”), set the stage for the aggressive promotion of OxyContin.

But the picture is further complicated, in my opinion, by the fact that Arthur Sackler was an arch-enemy of the tobacco industry, and from the 1960s to the 1980s he wrote numerous no-holds-barred editorials in his biweekly national newspaper for doctors, Medical Tribune (circulation 600,000), calling for tough action on the part of leaders in government, the mass media, the American Cancer Society, and hospitals against cigarette smoking and its promotion.

In a Sept. 11, 1978, editorial, “An American Tragedy,” Sackler railed against the “governmental schizophrenia in respect to cigarette smoking.” He noted the irony of the U.S. government spending “$600 million to subsidize tobacco crops and promote cigarette sales” while “the beneficiaries of this largesse, the cigarette companies, are trying to prevent HEW [the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare] from spending a mere $20 million to try to cut down the tragedy of lung cancer and heart disease associated with cigarette smoking.” Sackler condemned the “weasling of the U.S. delegation to the World Health Assembly,” headed by HEW Secretary Joseph A. Califano, Jr., for refusing to support a ban on cigarette advertising.

Sackler also accused President Carter of hypocrisy. “The spokesman for this administration, which claims to herald a new day in our political life, one free of rhetoric and double talk, of less bureaucracy and amenability to big business lobbies, was quick to proclaim the Constitutional right of newspapers to accept cigarette advertising and suggested, in the face of increasing governmental limitations on advertising of medical and therapeutic procedures, that when it comes to cigarette advertising restriction, ‘this touches on freedom of the press.’”

“What an obscenity to call upon the American Constitution to try to support those who are seeking to addict young people to a dangerous addicting substance which has brought the tragedies of cancer and heart disease to so many American families. What hypocrisy to ask at the very same time for more restrictive regulations on the actions of physicians and the use of their medicines as they fight against these and other deadly diseases.”

The irony that Arthur Sackler’s family would itself similarly be accused of addicting Americans is obvious. For that matter, it’s possible that the motive behind Sackler’s editorial was self-interest, i.e. aimed at fending off attacks on pharmaceutical advertising. But the parallels between the stated goals of litigation brought by the state attorneys general against the tobacco industry in the 1990s (i.e., allegedly to recover the costs of caring for victims of smoking) and the goals of today’s lawsuits against prescription opioid manufacturers are also worth considering.

The lawsuits by the states, counties, cities, and tribes against Purdue and the Sacklers do not demand that OxyContin be withdrawn from the market.

To the contrary, as The New York Times points out (Oct. 12, “Bankruptcy Judge Pauses State Suits Against Purdue and Sacklers”), they want prescriptions of the drug to continue so that all profits would go to pay the plaintiffs for the costs of the opioid epidemic.

Shades of the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) between the state attorneys general and the tobacco industry in 1998! For far from wanting to kill the goose that laid the golden eggs, the attorneys general effectively wanted the states to get a piece of the action…in perpetuity. As a result, instead of using a significant portion of the ongoing annual MSA payments to the states to fight smoking—less than 2% of it has been used for this purpose, state legislatures have become dependent on cigarette money in order to reduce budget deficits.

The Times also points out that although Purdue and the Sacklers have been “labeled as progenitors of the crisis,” the company claims that during the peak of the opioid epidemic between 2013 and 2016, it manufactured only 4% of prescription painkillers in the US. And it points out that its products were approved by the FDA and monitored by the Drug Enforcement Administration.

The plaintiffs and P.A.I.N. have also not directed their wrath or held demonstrations at the giant retail drugstore chains such as CVS, several of whose outlets were forced to close because of poor narcotic dispensing oversight, or Walgreens, which still sells cigarettes in its 8,000 stores.

Nor have they included medical societies whose journals accepted millions of dollars in advertising revenue to promote OxyContin and other prescription opioids.

A pusher becomes a patron

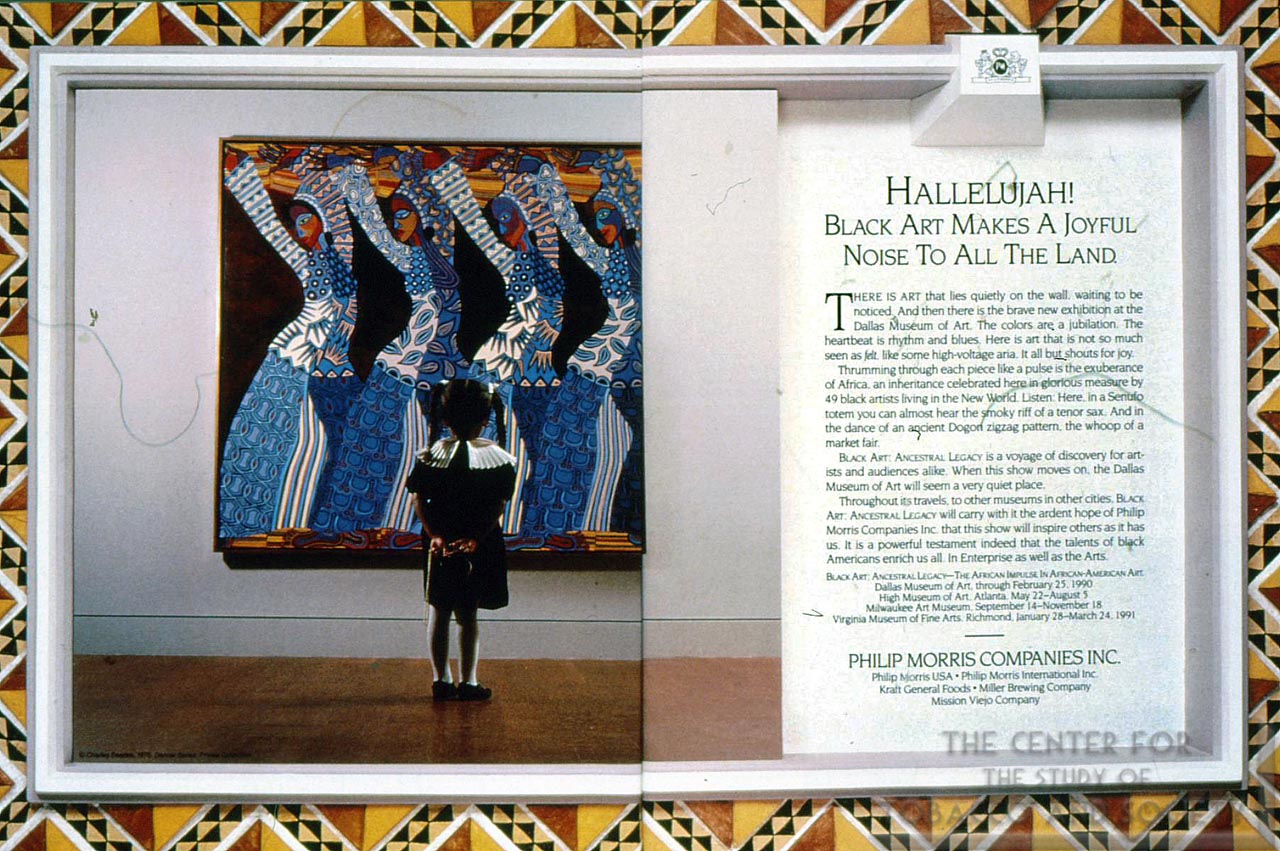

Although Philip Morris (which changed its name to altruistically-sounding Altria in 2003) began contributing to arts groups in Richmond, VA, home of its largest cigarette manufacturing plant, in the late-1950s, the payments that the cigarette maker has since made to nearly 200 art museums throughout the nation (plus countless dance troupes, opera companies, repertory theaters, libraries, and ethnic arts organizations)—the most cultural funding by any corporation—dramatically increased following publication of the landmark Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health in 1964.

For the past half-century, then, the money doled out by this super-patron of the arts has helped burnish the company’s nicotine-stained image and deflected attention away from the enormous body of peer-reviewed scientific evidence implicating cigarettes as the nation’s leading preventable cause of death and disease.

Lucre from the maker of Marlboro cigarettes has paid off by buying the complacency of opinion leaders. To put this funding into perspective, the $12.8 million that Philip Morris handed out to art museums and cultural groups in the U.S. at a high point of corporate charitable giving in 2002 represented just .001% (or one one-thousandth of one percent) of the nearly $12 billion in profits from the company’s cigarette sales that year. The Guardian reported on March 29 that, in 2018, Altria donated $3.8 million to the arts, while paying $5.4 billion in dividends to shareholders.

Moreover, donations to art museums are tax deductible, so it doesn’t cost shareholders a cent.

To be sure, the company has never hid its main intention. In an address to a conference on business and arts in 1979, Philip Morris chairman of the board George Weissman said, “For our company—perhaps for American business in general—this is only the beginning. The future will see an ever-closer partnership between business and the arts. The passing of the giant private patron, the emergence of the corporation as the controller of an enormous new medium of world-wide communications, the growing awareness of the corporation’s potential and responsibility for enlightenment, the ever-widening scope of the corporation’s horizons—these are factors that will cement lasting relationships with the arts.”

For the past half-century, then, the money doled out by this super-patron of the arts has helped burnish the company’s nicotine-stained image and def lected attention away from the enormous body of peer-reviewed scientific evidence implicating cigarettes as the nation’s leading preventable cause of death and disease.

In his foreword to Philip Morris and the Arts: A 30-Year Celebration, a coffee table book published by the cigarette maker in 1989, Tom Armstrong, the director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, a longstanding recipient of Philip Morris largesse for its Whitney Biennial and other exhibitions, gushed:

“Philip Morris became not just an art patron but one that stood at the cutting edge of contemporary sensibility…

“By becoming a patron of the arts, therefore, Philip Morris became a contributing member to many communities, many constituencies, and many good causes, a fact that was soon signaled by the shower of awards and tributes that began to descend upon the company…

“It is personally gratifying and encouraging because it gives great credibility to the hope that the people who ultimately support the arts will assist not for private gain or corporate profit but with a realization that life in the United States will be enriched and expanded through an appreciation and understanding of our cultural resource.”

The Smithsonian Institution has been one of the longest continuous solicitors and recipients of cigarette sponsorship money.

I first began raising concerns about the ethics of tobacco industry sponsorship of museums as at the annual meeting of the Chicago Historical Society in 1980 on the eve of the opening of a traveling exhibition at the museum, “Champions of American Sport,” which was curated by the Smithsonian and principally underwritten by Philip Morris.

In my remarks, I provided a brief overview of the insidious involvement of tobacco companies in sports. I cited the decades of aggressive marketing by Philip Morris aimed at associating its cigarette brands with athletic prowess, notably through Marlboro ads featuring National Football League stars Frank Gifford, Sam Huff, and others. I pointed out that 14 of the 24 Major League Baseball stadiums in 1980 had huge Marlboro billboards—all placed at key camera angles in order to be picked up on TV screens as a way of circumventing Congress’ 1971 ban on tobacco advertising on TV (RJ Reynolds’ Winston brand was on 8 billboards; only two stadiums lacked cigarette ads).

Drug abuse among professional athletes was receiving considerable attention in the mass media, I noted, and Major League Baseball was trying to have it both ways: trumpeting its anti-drug addiction programs on the one hand while helping push America’s leading lethal addiction, cigarette smoking, on the other.

The response to my objections by the Chicago Historical Society’s board of trustees was total silence, but the museum director pulled me aside afterwards to thank me for speaking out against the veritable takeover of his museum by Philip Morris—complete with ashtrays and give-away packs of Marlboro in the galleries.

Sponsorship of both sports and the arts were crucial parallel marketing strategies for Philip Morris in the decades following Congress’s 1971 ban of cigarette advertising on television.

The first major women’s professional tennis circuit, established in 1971 during the rise of the women’s rights movement, was sponsored by Philip Morris’ Virginia Slims cigarettes. Proceeds from the Jan. 14, 1977 Virginia Slims tournament were gratefully received by the Broward County chapter of the American Cancer Society.

![DOC housecall at the Metropolitan Museum of Art [Taking a Stand]](https://cdn.cancerletter.com/media/2019/10/DOC-housecall-at-the-Metropolitan-Museum-of-Art-Taking-a-Stand.jpg)

![DOC housecall at the Metropolitan Museum of Art [Taking a Stand]](https://cdn.cancerletter.com/media/2019/10/DOC-housecall-at-the-Metropolitan-Museum-of-Art-Taking-a-Stand.jpg)

By the 1980s, George Washington University and Boston University, among other educational institutions with medical schools and cancer centers, were hosting Virginia Slims tournaments.

In 1990, Mervyn Silverman, MD, the medical director of the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR) posed for photographs at the Virginia Slims of Houston holding an oversized check from Philip Morris. In 1994, MD Anderson president Mickey LeMaistre, MD, permitted his name to be listed as a member of the “Virginia Slims Legends Medical Advisory Committee,” along with six other physicians, including Michael DeBakey and Denton Cooley.

Buying respectability…and complacency

The epitome of chutzpah by the cigarette maker was its sponsorship of “The Vatican Collections: The Papacy and Art” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1983. In protest, I led 35 other physicians and students in a “house call” at the museum.

An article in The New York Times about our action quoted a spokesperson for the archdiocese of New York as saying, “’the sponsor is not Philip Morris as a cigarette company, but Philip Morris Inc.’ Since the corporation’s $3 million grant is to the museum, he said, ‘the Vatican does not have any necessity to answer’ such objections.”

In 1987, Philip Morris opened a branch of the Whitney Museum of American Art in the lobby of the company’s headquarters across from Grand Central Station. I once asked a class of sixth-graders visiting an exhibition there, “Kids, what does Philip Morris make?”

One little girl eagerly raised her hand and said, “I know: Paintings!”

By 1988, the company was so widely recognized as the leading benefactor of the arts that its CEO, Hamish Maxwell, was emboldened to write the following in the sponsor’s introduction to the exhibition “Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism,” at the Museum of Modern Art:

“Philip Morris is pleased to help present this tribute to the enduring value of creativity, experimentation, and innovation, qualities that we think are as important to business as they are to the arts. For whether the year is 1908 or 1989, in a rapidly changing world, not to take risks is the greatest risk of all.”

The company even coined the slogan, “It takes art to make a company great,” which it included in full-page color advertisements it purchased in major magazines and newspapers. In response, Berkeley artist Doug Minkler and I created a counter-advertisement, “Artists As Ashtrays,” with the suggestion for a more accurate Philip Morris motto, “It takes art to make complacency great.”

In 1994, when the New York City Council was debating a bill to ban smoking in restaurants and most other public places, Philip Morris not only threatened to move its headquarters and its 2000 employees back to Richmond, but also leaned on the arts organizations it funded to lobby and testify against the bill. Some did, as reported by The New York Times in a front-page story on Oct. 5, 1994 entitled, “Philip Morris Calls in IOUs in the Arts.”

According to Chin-tao Wu in her 2002 book, “Privatizing Culture: Corporate Art Intervention since the 1980s,” “By dispensing money as widely as Philip Morris had been doing, the tobacco companies were buying the critical silence of arts bureaucrats and their institutions…

“This is the moment, I would argue, at which the ‘cultural capital’ accumulated by the corporation is transferred, in the most naked manner, to political power, at the service of corporate economic interests.”

In 2007, while on a gallery tour at the Whitney, along with 30 other visitors, of an exhibition by artist Kara Walker, I asked a question of the docent as she praised the artist’s biting depictions of the exploitation of African Americans during the centuries of slavery and to the present.

“But why would the museum and the artist permit Philip Morris, a cigarette company, to sponsor this exhibition, considering that the smoking-related death rate from lung cancer and heart disease is so much higher among African Americans?”

The docent remained silent for several seconds, then resumed the tour.

With the implementation by the administration of Mayor Michael Bloomberg of further restrictions on cigarette smoking and the sale and promotion of tobacco products in New York City, Philip Morris finally made good on its threat to move its headquarters back to Richmond in 2007—thus taking nearly all of its arts funding dollars with it.

The New York Times, which had published hundreds of advertisements for Philip Morris-sponsored arts events over the preceding 25 years, conceded in an editorial, “End of An Era in Arts Funding:”

“We’ve always hated the basic product that Philip Morris sells, which has harmed millions of smokers and nonsmokers at immense cost. We’ve also admired its diverse and relatively unfearful support of the arts. There is no disputing its generosity, even though we shuddered at how easily large amounts of cash can buy neutrality and, eventually, respectability in a very influential part of the community…

By selling more Marlboros, it will be able to sponsor more art and buy more complacency. And, by buying more complacency, Philip Morris will be able to sell more Marlboros.

“The loss of Altria gives the art world a chance to shake its addiction to what has, in fact, always been tobacco money. Yes, that money was spent in the public interest, supporting institutions and programs and exhibitions that have greatly enriched us all culturally. But it’s also worth wondering about the real costs of that funding—the fact that for so many institutions Philip Morris ceased to mean tobacco and came to mean mainly a reliable check.”

The taxpayer-supported Smithsonian Institution has continued to solicit and accept funds from Altria, which remains one of its $25,000-a-year corporate sponsors. In recent years, the company has sponsored exhibitions at the U.S. National Portrait Gallery and the Renwick Gallery.

Altria also gave the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture one of the largest initial donations—“$1 million plus”—and, according to The Guardian, it gave $500,000 to the museum for its exhibition, “Double Victory: The African American Military Experience.” The irony of African Americans having been disproportionately afflicted with lung cancer and the main targets of the company’s menthol brands has apparently been lost on the museum’s officials and curators.

A current exhibit at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, “More Doctors Smoke Camels,” consisting of several nostalgic cigarette advertisements from the 1940s and 1950s with images of physicians lighting up, does not acknowledge the Smithsonian’s ongoing solicitation of money from Philip Morris or the cigarette company’s ongoing aggressive marketing of Marlboro around the world.

There’s no question that tobacco money has been an even stronger addiction for art museums than that from the maker of prescription opioids. Why else would already wealthy museums have needed more and more of it?

Singling out the Sackler family for condemnation is problematic. The arts philanthropy that the late Arthur Sackler initiated in the 1970s–two decades before OxyContin was introduced—had nothing whatsoever to do with burnishing any of Purdue Pharma’s brand names. It was about the family name—the thing called immortality.

In stark contrast, Philip Morris, which still uses the arts to reach opinion-leaders and help stave off efforts to prevent it from hooking a new generation on Marlboro and JUUL (the cigarette-maker bought a third of JUUL Labs Inc. last year), continues to crank out Marlboros. By selling more Marlboros, it will be able to sponsor more art and buy more complacency. And, by buying more complacency, Philip Morris will be able to sell more Marlboros.

I can understand why Nan Goldin is directing her ire at the aggressive marketers of prescription opioids. I only wish she would put out her cigarette, and, diversifying her efforts, lead a protest against its maker.

Museum Malignancy: Tobacco Industry Sponsorship of the Arts, an online exhibition curated by Blum, explores the collaboration between art museums and the maker of the world’s top-selling cigarette, Marlboro.