This story is part of The Cancer Letter’s ongoing coverage of COVID-19’s impact on oncology. A full list of our coverage, as well as the latest meeting cancellations, is available here.

Radiation visits—much like preventative screenings, surgery, chemotherapy and screening—were delayed or canceled at the peak of COVID-19 in the United States.

Now, the patients are returning, in some cases creating small upticks in demand for treatments that were delayed in March, April and May. In a few institutions, the return of the patients is creating wich-welcomed backlogs.

In a survey conducted by the American Society for Radiation Oncology April 16-30, 85% of oncology practices said radiation oncology appointments at their practices had decreased by about a third, even though their doors remained open through the pandemic. ASTRO received responses from 222 physician leaders of radiation oncology practices.

In the survey, 82% of respondents cited delayed/deferred treatment and 81% cited decreases in the number of patients being referred for radiation therapy.

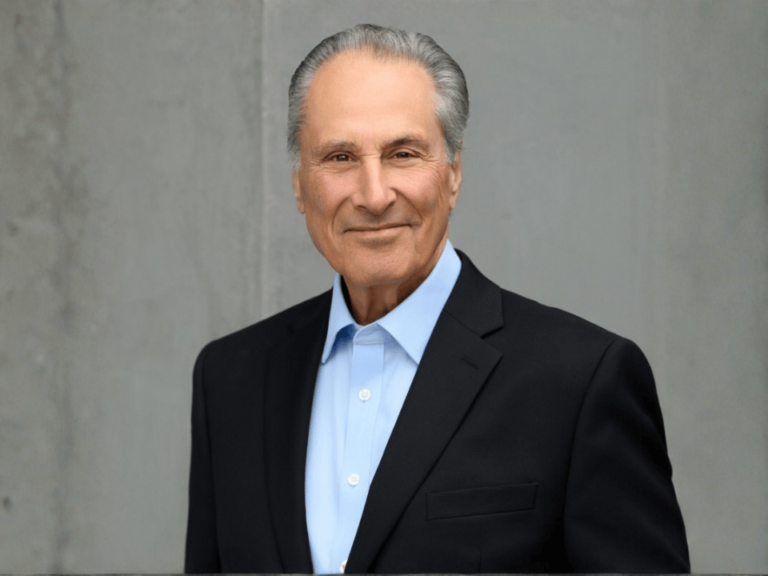

“What we’re trying to do with the survey data is to dive deeper into that. We don’t have the answers yet, because we simply are still collecting the data. But one of the questions we do want to ask is—if there is a differential impact of COVID specific to cancer care, and to radiation delivery, that may or may not require some kind of policy-level intervention, or practice-level intervention,” David Schwartz, co-author of the ASTRO study, said to The Cancer Letter.

“This is where it’s now a global, community-wide freakout. What impacts some of these things is not just the physicians, nor even the disease—it’s also the patient and community’s response to an overwhelming threat. You’re seeing people not showing up for surveillance,” said Schwartz, professor and chair of the Department of Radiation Oncology at University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

Data from another survey, conducted by the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, showed that 79% of patients in active cancer treatment reported a delay to their health care (up from 27% in a previous survey). Seventeen percent of patients in active treatment reported delays to their cancer therapy—chemotherapy, radiation, or hormone therapy. The survey polled more than 1,200 cancer patients and survivors.

“There are certain feeder cancers that keep the radiation oncology units busy. Those need to be diagnosed as a process. That process was broken—is broken,” Len Lichtenfeld, deputy chief medical officer at ACS, said to The Cancer Letter. “A breast cancer patient needs radiation following a lumpectomy, a prostatectomy that needs radiation, lung cancer patients that may benefit from radiation.”

In the ACS CAN survey, 17% reported that the threat of COVID-19 prevented them from seeing a doctor for an illness or injury for which they would have otherwise sought treatment. Among those who delayed or canceled care, 59% said the decision was made by their health care provider.

Nearly half (46%) of cancer patients and survivors reported a deterioration to their financial situation that affected their ability to pay for care, an increase from 38% in the ACS CAN survey released in April.

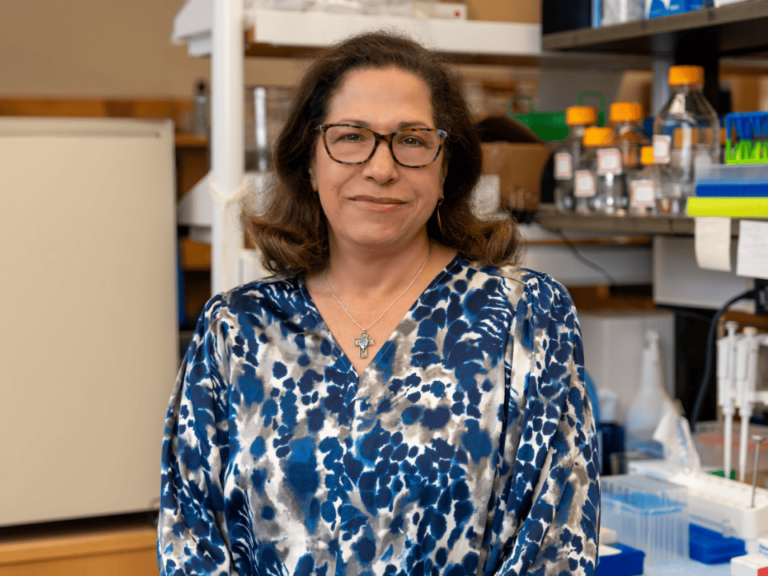

“What we’re going to see is a backlog of more advanced presentations in the future, with patients whose care has been affected and delayed by the pandemic,” Sue S. Yom, professor in the Departments of Radiation Oncology and Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery at University of California, San Francisco, said to The Cancer Letter.

“Radiation oncology is unique in that it requires such a specific commitment of time and resources over a very intensive period. I don’t think that that is something that all patients have the ability to do right now,” Yom said.

The uptick in demand for services is especially dramatic at New York’s Mount Sinai Health System. Mount Sinai deferred appointments at the beginning of the crisis, and made room in its hospitals for an expected overflow of COVID-19 cases in the city. That overflow never came.

“We have some outpatient facilities that patients were able to go to. Once we realized we were on the other side of the peak, and there wasn’t really going to be a need to use our clinical areas, we started opening them up again and ramping up,” Kenneth Rosenzweig, professor and system chair of radiation oncology at Mount Sinai Health System, said to The Cancer Letter.

“As of today, the end of May, we’re actually at a higher volume of patients on treatment than our typical average,” Rosenzweig said. “I think part of that, another reason is that some of the patients who had been delayed are now on treatment. So, there was a bit of a backlog—and now that’s opened up.”

Radiation appointments at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center plummeted during the peak of COVID-19. Now, MSK is seeing increases in radiation oncology appointments.

“It was certainly expected that during that time where you would see, particularly in April—when the incidence [of COVID-19] was so high here, and we were seeing the ER flooded with patients—that we would see a reduction in radiation oncology visits,” Daniel Gomez, director of thoracic radiation oncology, and chief of radiation oncology, Manhattan Service, at MSK, said to The Cancer Letter.

“Now that that’s subsided, you’re seeing the opposite effect, and with regard to patients wanting to come in and get their cancers treated.”

“Patchwork quilt”

On a policy level in the U.S., it is up to the states and counties to institute COVID-19 guidelines.

“As the country learns how to deal with this—in policies, we’re downstream with those things. What might be going up in Tennessee might not be going up in New York or Chicago,” Daniel V. Wakefield, co-author of the ASTRO survey, said to The Cancer Letter.

“What we’ll see as a patchwork quilt of changes based on local government ordinances across the country, on not just a state level, but really, on city-to-city level,” said Wakefield, chief resident in the Department of Radiation Oncology at University of Tennessee Health Science Center and MPH ’20 candidate at Harvard University.

Cancer hospitals are a part of this patchwork quilt.

“What you are seeing is different phases of a pandemic. Everyone’s been in different acute and recovery phases,” UCSF’s Yom said. “And I will say that now that San Francisco is sort of officially in reopening and recovery, we definitely are seeing a very dramatic uptick in our consultations. But, remember, the time from consultation to initiation of treatment can be a week to several weeks.”

“What we’re seeing now isn’t reflected yet, but our numbers have been trending up for about the past week or two.”

Many cancer experts have pointed out that COVID-19 has exacerbated health disparities, making the underserved more underserved (The Cancer Letter, May 22).

“The maps that we see of COVID infection rate positivity can actually be overlayed onto cancer incidence and cancer mortality,” said Schwartz, who is also in charge of COVID-19 testing and data collection in Memphis. “It comes down to one overriding issue: social determinants of health.”

“This can be manifested as cancer, but also as chronic disease. And that’s another issue that we see here in Memphis—is that cancer incidences also overlap very tightly with the incidence of hypertension, especially uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, stroke, heart attack, obesity, food insecurity—all of those things,” Schwartz said.

Rural vs. urban

David Beyer, medical director of radiation oncology at the Cancer Centers of Northern Arizona Healthcare, has delayed radiation treatments and pivoted to telehealth whenever possible out of concern for the health of his staff and patients.

Beyer is the only physician at his clinic.

“We don’t know what’s going to happen. We don’t know who in our department is going to get sick. We are a small rural clinic,” Beyer said. “If I get sick or have to quarantine myself for two weeks, we have a serious problem. We have two radiation therapy technologists, and they actually deliver the treatments on a day-to-day basis to each patient. We have two of them. If one of them gets sick, or God forbid both of them get sick or have to self-quarantine, we have a problem.”

Beyer’s clinic used to treat 25-30 patients per day—now he sees about 15-20.

“There is one place where you can get screening mammograms. They are not doing screening mammograms right now,” Beyer said. “They made the same choice to shut down routine screening mammography. So, we’re not seeing breast cancer patients that otherwise might’ve been diagnosed right now with an asymptomatic breast cancer.”

Still, Beyer’s location in Sedona has been relatively spared from the coronavirus. As of May 25, his local hospital had one confirmed case of the disease. His staff members have been asking, “When are we going to start seeing our new patients in person, instead of over the computer?”

“My answer is, ‘Not yet,’” Beyer said. “We’re still sticking with the telehealth options as much as possible, so that we reduce the risk of exposing us and exposing them.”

“The next county over is the Navajo Nation. It exploded there. They have one of the highest rates of COVID anywhere in the country right now. It’s not that it’s not close—it’s not right here. What we’re doing works right now, for us,” Beyer said.

In Memphis, where ASTRO study architects Schwartz and Wakefield treat cancer patients, the spread of COVID-19 has been moderate. Nonetheless, the number of radiation oncology appointments at their clinic has declined.

“Ours is a center where we don’t have high concentrations of people living on top of each other like New York, or San Francisco, or Washington or Los Angeles—and we experienced a much different pandemic,” Wakefield said. “Ours was more of a slow burn. And to be frank, now I think it’s starting to have more effect than what we were seeing in New York six weeks ago.”

The population in Memphis tends to be poor and rural, Wakefield said. People drive their cars to the clinic rather than walk or take public transportation. High poverty rates and accompanying social risks leave its population and rural practices vulnerable.

In Memphis, there is a rural-urban divide, Schwartz said.

“Memphis is in an agricultural area, but it represents the largest metropolitan area in this region of the mid-South. We do get rural populations, and do refer back patients to referral to rural practices,” Schwartz said. “My impression is that rural practices probably have been struggling, simply because they do depend very much on a steady stream of referrals to maintain the nuts and bolts of their practices.”

What comes next?

Now, Schwartz and Wakefield are conducting a follow-up survey for ASTRO. That study is likely to show that demand for radiation oncology is continuing to rise.

“Now, as the general relaxing of social distancing and restrictive measures have kind of been released at least to some degree, and the nation slowly returns to business, we’re starting to see a larger influx of patient numbers,” Schwartz said. “I also think, probably, the patients are more comfortable to come in.

“Whatever loss of volume and losses of referrals that we got, I have to believe that the patients, too, are part of that issue. They simply did not feel comfortable coming in anywhere, let alone to a healthcare facility that was seeing patients with COVID,” Schwartz said.

If patients are beginning to receive treatment for cancer that requires radiation after the fact, it may take weeks from there to show up in the data.

“The number of cases of cancer—the screening test, the diagnoses, the visits starting with a primary care doctor, maybe a urologist—all of those visits are way down,” ACS’s Lichtenfeld said. “The normal progress of activity starts with diagnosis, and the treatment. And consequently, if the diagnoses are decreased because people aren’t going to see the doctor, then I wouldn’t be surprised to see that radiation therapy is decreased.

“One of the major messages that’s been so hard to deliver during this pandemic has been, if you have to a or symptom of cancer, you need to see somebody and you need to—notwithstanding concerns about the risk of going to see a doctor—you have to break through that concern and get yourself taken care of.”