This point is easily overlooked: Monica Bertagnolli has two jobs, not one. She is the director of the National Cancer Institute and head of the National Cancer Program.

This is because the National Cancer Act of 1971, in addition to establishing the structures for funding research, is a visionary public health legislation that bestows the NCI director with these twain missions.

“That’s my job. I have to say, I’m feeling very fortunate,” Bertagnolli said.

Though many of Bertagnolli’s predecessors in the eleventh-floor suite in NIH Building 31 focused exclusively on cancer research, she has focused also on the public health component of her job—that of the architect of the National Cancer Program—in an unprecedented way.

During her first six months, Bertagnolli has been sorting out the fine points of her authority even as she was undergoing treatment for breast cancer. In a conversation with The Cancer Letter, she parsed through the history and law that underpin her strategy for NCI.

The National Cancer Act states that the NCI director’s mission is not limited to NCI, NIH, HHS, or even the U.S. government. It’s about creating a plan for the National Cancer Program. “So, I’ve been thinking about that a lot, particularly because our president, President Biden, also takes that very seriously,” Bertagnolli said.

The law states:

In carrying out the National Cancer Program, the Director of the National Cancer Institute shall: (1) With the advice of the National Cancer Advisory Board, plan and develop an expanded, intensified, and coordinated cancer research program encompassing the programs of the National Cancer Institute, related programs of the other research institutes, and other Federal and non-Federal programs.

Bertagnolli’s position is unique because her mandate comes from Biden, who is active on cancer and is pushing for a reauthorization of the National Cancer Act—a law that is now more than five decades old—to reflect the science and scientific institutions that didn’t exist at the time President Richard M. Nixon signed the NCA at a pre-Christmas ceremony at the White House.

“The reauthorization will update the nation’s cancer research and care systems to put modern American innovation fully to work to end cancer as we know it,” the White House said in a Feb. 7 fact sheet. “This includes standing up clinical trial networks, creating new data systems that break down silos, and ensuring that knowledge gained through research is available to as many experts as possible, so we can find answers faster and make a difference for patients.”

Also, Biden’s fiscal year 2024 budget request seeks to reauthorize the Cancer Moonshot through 2026 and provide $2.9 billion in mandatory funding in 2025 and 2026, $1.45 billion each year (The Cancer Letter, March 10, 2023).

“In the State of the Union this year, he reiterated that he expected the Cancer Moonshot to also be an all-of-government, all-of-society approach,” Bertagnolli said. “So, we had to do some deep thinking about what it would take to make that happen.”

The NCI Cancer Plan, published April 3, is organized around eight goals that span the spectrum of cancer prevention, treatment, and survivorship—aimed at achieving the Moonshot’s objective of cutting the cancer mortality rate by half within 25 years (The Cancer Letter, April 7, 2023).

“The Moonshot is the call to action and the charge at the level of the president that says, ‘Hey, we need to end cancer as we know it, and we all need to work together,’” Bertagnolli said. “The Cancer Plan is in service of that, overall. So, there’s no daylight between the two.”

Bertagnolli’s plan has three distinct phases for engagement:

- Read the plan and define your role in relation to its goals,

- Build infrastructure to support research and data-sharing, and

- Create a learning environment that seamlessly combines clinical and research activities.

“When people read it, we want them to think about, well, what could their role be? What do people want to do?” Bertagnolli said. “We don’t want to tell people what to do. We want to find out who’s already engaged, who’s already interested, who this speaks to.”

The cancer centers are a part of the NCA, but clinical trials cooperative groups, which were already in existence in 1971, are not included.

Bertagnolli, a former group chair, has given the group chairs and leaders of other clinical trials networks, as well as FDA and the industry, a prominent role in her Cancer Plan—and as collaborators in NCI’s Clinical Trials Innovation Unit (The Cancer Letter, Feb. 10, 2023).

This is not the first effort to reimagine the National Cancer Act.

Circa 2000, the American Cancer Society, then at the apex of its fundraising prowess, hired PR firms to launch a process called the National Dialogue on Cancer, which sought to rewrite the NCA and appoint a “cancer czar.” In that schema, NCI and research would have been reduced to just one constituency represented around the table.

Richard Klausner, the NCI director at the time, was strongly opposed to this schema, seeing it as usurpation of NCI’s role as the lead agency of the National Cancer Program.

The Cancer Letter’s coverage of the dialogue—which later was renamed C-Change—is available here.

The scope of the NCI director’s job has to evolve to keep pace with sociopolitical currents, Bertagnolli said.

“If you think about it, so many things in our society demand the attention of an NCI director as never before, which is a good thing—health equity, trust, engaging trust throughout our community, making sure that we reach every corner of society,” Bertagnolli said.

“The role of NCI director is really very gratifying, because at this time, people are really excited and ready to do this. The main part of the job is just figuring out the infrastructure, the structures, the ability to make it happen. And that’s really what it’s all about.

“It really is a time like no other.”

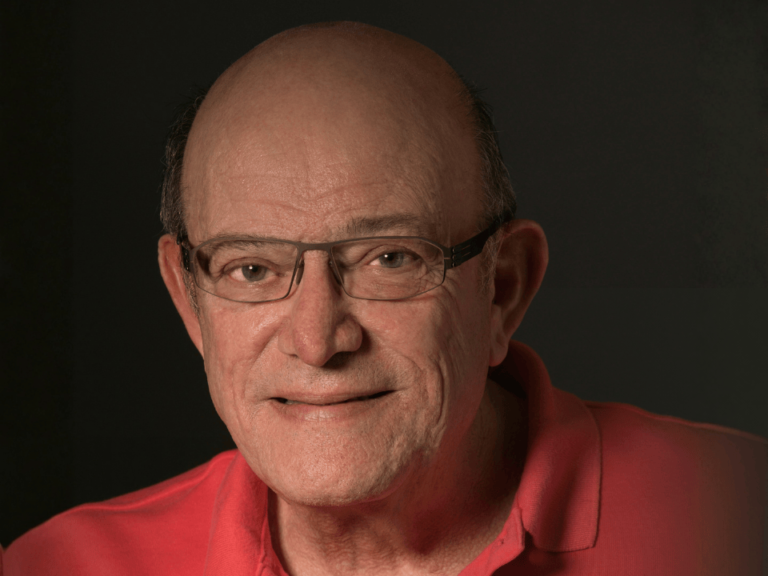

Bertagnolli spoke with Paul Goldberg, editor and publisher of The Cancer Letter, and Matthew Ong, associate editor of The Cancer Letter.

Paul Goldberg: Monica, thank you very much for finding the time to talk with us. You’ve been the NCI director for six months. It’s been eventful, and it sounds like you haven’t missed a beat.

Monica Bertagnolli: It’s been exciting. I’m having a really wonderful and inspiring time. It’s really been great.

Matthew Ong: You’ve been making the rounds to talk about the National Cancer Plan. And as director of NCI, you are the head of the institute and head of the National Cancer Program.

This has been important to some of your predecessors, and, arguably, puzzling to others—that Paul and I have seen; Paul has seen more than I have—but you seem to care about both of these jobs.

Could you define what these jobs are to you?

MB: Absolutely.

So, the National Cancer Act of 1971 says that the director of the NCI needs to put together, obviously, plans for the agency itself, the institute itself, and what the institute will do in terms of cancer research, but also is responsible for thinking a little more broadly than that, and really helping coordinate a nationwide plan for how we are going to eliminate suffering from cancer.

And the act itself says not just NCI, not just NIH, not even just government, but other federal and non-federal sources. So, I’ve been thinking about that a lot, particularly because our president, President Biden, also views that very seriously.

In the State of the Union this year, he reiterated that he expected the Cancer Moonshot to also be an all-of-government, all-of-society approach. So, we had to do some deep thinking about what it would take to make that happen.

And an all-of-government, all-of-society approach doesn’t happen without an intentional strategy, an intentional plan for how you can bring that about.

Just saying it doesn’t make it so.

So, we really thought of the National Cancer Plan as a tool, something we could use to bring this about, and what is the “this”?

The “this” is we need to end cancer as we know it.

First thing we did was decide, what does that mean?

And so, that means that any person with cancer lives a full and active life free from harmful side effects, either from the cancer or from the treatment. And that, better yet, cancer is prevented, so that people don’t have to ever face that diagnosis.

So, that’s what it means to end cancer as we know it. If you have cancer, you can live well just in spite of it and overcome it. And, hopefully, more people will never have cancer.

That’s what we have to do. So, how are we going to do that?

PG: Can we just go back a little bit to the documents? Because as for the National Cancer Plan, let’s nerd out on history a little bit.

Back in 1971, the word “plan” showed up a few times in the National Cancer Act. The director—not you, you were way too young to be the NCI director—has to come up with a plan for the program.

So, here you are 50 years later, and you decide that you need the plan. Now, is the plan going to become a new National Cancer Act? Or is the plan going to include the Moonshot and then be turned into legislation?

MB: The plan was designed to help us all work together to eliminate suffering from cancer.

So, what we did is we got a very broad team of people—scientists, researchers, patient advocates, people from within government and without—together.

And we said, okay, what do we need to see the world look like?

What do we need to achieve in order to eliminate suffering from cancer? First, what do we need to do? These are the goals. There are eight goals of the National Cancer Plan, and the goals are really about, what does success look like?

They were framed that way. What would success look like? That’s basically the core of the plan. What does success look like? And then a call for how we can bring about this state that will help us end cancer as we know it.

So, underneath each of these goals is a description of where we are today, how we’re not achieving this yet today, but also some very hopeful comments about how we are making great progress. And then, there’s also a list of particular areas under each goal where NCI is really playing a role in helping to achieve those goals.

That’s the plan. But the most important part of the plan is to say, it’s not just NCI, it’s not just NIH, it’s not just the government. Everybody has to help us achieve these goals.

And if you read the goals, you can see that there is no way can NCI achieve these goals alone.

PG: But you’re still the general running the operation, right?

MB: Well, I would refer to the NCI director more as a coordinator than a general.

This is a collaborative effort, but yes, I guess the buck stops here when it comes to, let’s make sure this plan gets out there, let’s make sure this plan is achieving what it intends to achieve, and it intends to achieve three things.

Number one, help us implement what we know already works. Number two, help us supercharge discovery and innovation so that we can achieve these goals, because we’re not there yet. We haven’t achieved any of these goals yet, and we need to. So supercharge innovation and discovery, and that means working together, bridging gaps to do that.

And then, the third thing the plan needs to do is to be a living document, or a durable framework, so that it works for today, it’s a big call for action to today, but as we go along, as we make progress, it can be modified.

So, it can’t just be, here’s a nice document we put out in 2023, and now no one’s going to think about it or be working with it in the future. It’s got to be a living document.

So, those are the three critical parts.

Right now, we’re in step one. And step one is, here’s the goals that have been developed by this broad community. We want to get them out there as widely as we possibly can. And what we’re asking is we’re asking everyone to read the plan and to tell us what you can contribute.

It’s not a to-do list in any way. It’s here’s where we need to go, here’s what we need to achieve now, who can help us? Please let us know who is willing and able to help. That’s step one. We’ll be working on that for the next six months or so, really, really diligently.

And soon—and even immediately for some things—we will then be into, okay, what are the gaps we need to bridge? Who do we need to bring together? Who has these goals in common that maybe haven’t been collaborating, or haven’t been working together in the past?

I think the first phase of the plan, the most important thing it’s going to do is to help us identify which people, organizations, agencies have shared goals that aren’t working together for those shared goals yet.

See what I mean? And there’s a lot of this. We all know it’s pretty amazing when you start asking the question, how many of the different parts of government and parts of society really share these goals, but they’re not working together?

So, that’s the first part. Find out who’s sharing these goals, find out what parts of these plans really mean something to individuals or organizations, and then do the best we can to bring those together to see how progress can be accelerated by working together. That’s phase one.

Phase two will be convening meetings. Phase two will be what can we do as the National Cancer Institute, to bring collaborators together to foster those collaborations, to help them thrive through both funding and provision of infrastructure.

There’s a lot to be said for, we need better infrastructure to help us collaborate. And that will be phase two.

Then, we’ll just keep doing this over and over again until we succeed. And that’s the other final thing, and I think the Moonshot is all about this.

The Moonshot is the call to action. The Moonshot is the call for persistence and commitment, not just a one-time plan, and it goes away, but persistence and commitment and dedication until we achieve these goals.

PG: Is there a National Cancer Act of 2024 at the end of that, or no?

MB: Well, I think you noticed in the State of the Union speech, President Biden called for perhaps a reauthorization of the National Cancer Act of 1971.

So, I do believe that the White House is thinking about that and maybe working toward that.

I don’t have any specifics for you. I just know what we all know from the State of the Union speech. And we will look forward to that, because there are lots of ways that our work can be facilitated, certainly. There are ways that policy or authorities can help us move faster and better.

Updating the governmental structures that allow us to do our work is something that we should visit constantly. And I believe the president has identified that since there hasn’t been an update since 1971. It might be time to give it a fresh look.

PG: There was an NIH Revitalization Act of 1993; right? So, NCI didn’t get a reauthorization. There was an effort made by the American Cancer Society, but I will not bug you with that. I’m sure you were reading it. I was covering it. It was really how not to do it.

MB: Well, if the president decides fully to go forward with this, which I believe he probably will, our approach will be to work across NIH and HHS, because again, we view our work through a collaborative lens.

So, NCI is going to be enormously more effective if it can work across the other agencies of HHS. And we can make that work. We can facilitate that by any means necessary.

That’s one of the discussions that I know we will be having very soon. If the reauthorization goes forward, it’s going to be about, how can we work together better?

PG: Also, one big issue is the number of hats you get to wear. You really need two; right? The NCI director and the head of the National Cancer Program.

MB: Yes. I’m so honored to be the director of the NCI, and I’m so pleased to find in this position that there are so many who share these common goals.

What a wonderful job it is to have a job where everyone really shares these goals.

And really, the main part of the job is just figuring out the infrastructure, the structures, the ability to make it happen.

And that’s really what it’s all about. And that’s why the role of NCI director is really very gratifying, because at this time, people are really excited and ready to do this.

MO: And speaking of structure, the Pragmatica-Lung trial is opening for enrollment.

MB: Yes, it’s open in 126 sites.

MO: That’s fast!

MB: I know. And the study was just a thought last July, August. And already, it’s open.

MO: And this also fits perfectly into the National Cancer Plan; right? Because it includes cancer centers and the clinical trials network. You have a prominent role for the group chairs.

MB: For Pragmatica, yes, and here’s how it fits into the plan. It’s a collaboration between FDA, NCI and the many national clinical trials, network partners, and all the sites through the National Clinical Trials Network.

So, it’s a terrific collaboration between those three main teams to bring this about in record speed.

Finally, there’s two other collaborative partners, Merck and Lily. Without their partnership and engagement, we wouldn’t have been able to achieve the nice start that we have with Pragmatica. So, it really is four-way: industry, two government agencies, and our extramural research community.

PG: That’s an example of what you were talking about that’s very specific.

To me, that’s the guts of what’s on the table now, this panel that you’ve created, because—let me nerd out on history a little bit more—cooperative groups are not in the National Cancer Act of 1971.

The cancer centers are as a network of cancer centers, as part of the plan that the director has to make in 1971.

MB: So, two things.

Number one, the National Clinical Trials Network and the NCORP are national treasures as far as I’m concerned.

These really allow us to bring cancer research, cancer clinical research to almost every corner of the United States. They are located in and serving small rural communities, serving inner-city disadvantaged populations, as well as the cancer centers and all the community centers.

Those are the vehicle that’s allowing us to bring research across the entire United States and with even some international population. That’s an absolute treasure.

The NCTN and NCORP can clearly do more and should do more. These structures that are in the form of the NCTN have been around since the 1950s and have delivered so much.

You all know, I think it’s very public that I’m being treated for breast cancer.

Well, the data that is guiding my care came out in the NCTN, or it’s precursors—all of my care.

So, I’m incredibly grateful to this national treasure personally, because it’s the data that’s informing the care that I’m receiving today.

I can say, as a patient, just how critical those structures are. And I can say, as a former leader of one of the networks and now NCI director, that that network can do so much more.

I’m really excited to see that get supercharged.

You’ve also illustrated one important thing about the plan, and this is how the goals—if you look at the goals, the prevent cancer, detect cancer early, better treatment—eliminate inequities. There’s not a goal to do clinical research.

Every single one of those goals requires great clinical research, very broad, very equitable, very robust clinical research infrastructure. Every single one of those goals requires data and data sharing and innovation with data sharing.

The other thing I will bring about in order to achieve the plan—we also require real attention to our clinical trials networks, the ability to do trials, our design of trials, our handling and understanding and technology associated with data.

Those are two related core infrastructure elements that serve the entire plan from top to bottom. And that’s another really key focus, frankly, as NCI director, is advocating for those two important structures.

And then, finally, definitely not last, the entire basic fundamental science infrastructure that fuels everything we can’t ignore. That’s part of our foundation. So, those main areas, maintaining and growing those infrastructures, are critical to the success of the plan.

PG: With the Clinical Trials Innovation Unit, there are other agencies involved, as well as the group chairs?

MB: The Clinical Trials Innovation Unit, this was something that was started since I came to NCI, and it recognizes that when it comes to clinical trials, we need to do more.

We need to do better, and we need to change and innovate—always. And clinical trials are enormously complex. And the National Clinical Trials Network is doing really important work right now with our existing structures.

So, in order to really innovate and break the mold and frankly take some risks, we decided the best way to do it was to provide a dedicated team at NCI in collaboration with FDA and the leaders of the clinical trials groups to innovate. The Clinical Trials Innovation Unit is about really new, different, break-the-mold ideas.

The most important part of the plan is to say, it’s not just NCI, it’s not just NIH, it’s not just the government. Everybody has to help us achieve these goals. And if you read the goals, you can see that there is no way can NCI achieve these goals alone.

The regular operations of the NCTN and the NCORP need to keep going. They’re doing amazing work. We’re not disrupting any of that. That work needs to go on the way it has, but the unit itself is to really start breaking the mold.

And the Pragmatica trial is a great example of something that unit is intended to do much more of. It was, get everyone together and really supercharge the process of getting an important innovative trial out to the community.

We could do that within the unit without disrupting the really important ongoing activities of the NCTN and NCORP. And we expect to see more. We expect to see more innovations, and they can be in anything. They can be in data management, they can be in integration with the basic science community.

They could be in biomarker development work. They could be in understanding new endpoints, they could be in finding new collaborators. Anything is on the table for that innovation unit.

Finally, with the FDA there as a partner, we’re making sure that the innovation unit is not only serving the needs of the cancer community to deliver new, better, quicker science.

It’s also serving the needs that we have for regulatory approval of important new devices and treatments.

Keeping those two close is really key to the success of the innovation strategy.

PG: I’m looking at the political innovation strategy point of view, and what I’m seeing is that you are wearing the hat of both the NCI director and the hat of the head of the National Cancer Program, which is key.

MB: I hope so. That’s my job.

I have to say, I’m feeling very fortunate. I have to give a big thanks to the amazing team at NCI, because as you can see, I stepped into a job trying to wear two hats from the very beginning as a new leader.

And the team has been incredibly supportive and responsive and has allowed me to do this so well.

PG: A lot of your predecessors, as Matt pointed out, didn’t know about the other hat, or didn’t care about the other hat, which comes with the job—the head of the National Cancer Program.

They knew about the NCI director’s job, of course.

We can go through the list of those who cared and those who didn’t care.

We won’t, but we can.

MB: It’s a different time—2023 is a time like no other in the history of the National Cancer Institute.

Really, if you think about it, so many things in our society demand the attention of an NCI director as never before, which is a good thing—health equity, trust, engaging trust throughout our community, making sure that we reach every corner of society.

How do we interact properly and to the greatest effectiveness with partners like industry or with partners like FDA?

And how do we finish up the last mile to improving people’s lives? Which means we have to be able to conduct cancer care delivery research and implementation science.

That’s a very new thing for the National Cancer Institute within the last decade or so.

It really is a time like no other.

MO: And speaking of a time like no other, is the Cancer Plan also reflective of the science that is going on now?

Because, I mean, the National Cancer Act was written long before we were able to describe tumors at the molecular level.

MB: Right. Yes, and I hope that everyone interested in conquering cancer can read the plan and see some of what they care about within the plan somewhere—really fundamental basic science is throughout really every single one of the goals has some.

I suppose maybe healthcare delivery or deliver optimal care doesn’t have any fundamental molecular biology there, but it could, if there are new innovative strategies to have some kind of a device or a delivery, a system that really radically changes our ability to deliver care, well, it belongs there too.

So, fundamental research is in every single goal. But every single goal also includes the last mile, which means something that is meaningful to a person or a patient. That’s also really key.

I’m a clinician. Other NCI directors have been clinicians. I think I can tell you that it gives a particular emphasis on making sure we impact people’s lives to what I care about as NCI director.

PG: Well, not to derail this, but to derail this, these couple of weeks have been very scary in terms of what’s been coming down in the judiciary—the federal judges in Texas.

One gutted the USPSTF, and with it evidence-based medicine, or is trying to do so.

And the other, of course, now is going after validity of drug approval in the United States.

How is this going to affect the goal—I didn’t mean to be snide—of cutting cancer mortality by half in the next 25 years?

MB: Certainly, we have a lot of challenges in our nation right now with clashing viewpoints on how our society should look, for example, or what are the limits of our laws?

What are our authorities?

I have to say, another challenge may be one of the most important reasons for putting forward a National Cancer Plan. Because we can all agree on those goals. We can argue about how we get there. We can debate that. We can come up with different strategies.

But those eight goals of the National Cancer Program, we can all agree on them and use them, as a starting point to make progress, including things like the issues that can be really contentious.

And I think the other thing that is helpful is that you need a framework to get to real specifics and understand if we’re going to come together, if opposing viewpoints are going to come together, then you have to rally around a common goal, and then you have to get into specifics so that we make sure we’re really communicating properly.

That’s another thing that I think has really been unfortunate about what’s happened recently in our society: there’s a lot of communication that stays in individual silos.

And we definitely need to find much more effective common ground for better communication.

I think that’s going to help a lot.

MO: What does the all-of-government approach really look like with the National Cancer Plan? You’ve talked about what FDA can do; could you also talk about concrete details of, say, what CDC or ARPA-H can do to contribute to these goals of the National Cancer Plan?

MB: It’s all-of-government, so you’ve brought up some of the agencies of Health and Human Services, which obviously have a big role in executing the National Cancer Plan.

NCI, long before me, had really fruitful collaborations with CDC and CMS, the Office of the National Coordinator, etc.

NCI also has great collaborations with the Department of Defense and the VA and the Environmental Protection Agency—all those things in our environment that can introduce risk of cancer.

So, these collaborations have been there for a long time.

Some of them, though, are even newly emerging, newly recognized. Housing and Urban Development and the role that can play in helping us to eliminate inequity that leads to health disparities, that’s another agency that maybe we didn’t think about, a government arm that we didn’t think about before that are being drawn in because of the goals of the National Cancer Plan.

Finally, I had an opportunity to present the plan to the deputies of the Cabinet recently, which was convened as part of the Cancer Moonshot.

Danielle Carnival [White House coordinator for the Moonshot] and I were both there presenting the plan, and it was really wonderful to see how engaged the deputies were in the plan itself, and how seriously they were considering what each of those governmental bodies would be able to contribute.

So, they’re fully engaged in phase one. We’ll see where we go from there. And that’s the highest cabinet level of the United States. Pretty exciting.

PG: It’s actually unprecedented, even including the National Cancer Act, when you think about it, because that was kind of a very different process.

But what is your ask of the cancer centers and the academic community and community docs as well?

Well, of course, advocacy.

But what can people do to take part in the cancer plan, and what are the prompts that they should be watching out for?

MB: The first part of this is we just want everybody to read it, to see what the goals are. And when people read it, we want them to think about, well, what could their role be? What do people want to do?

Like I said, we don’t want to tell people what to do. We want to find out who’s already engaged, who’s already interested, who this speaks to. So, that’s number one.

Number two, our ask is also that we need infrastructure to support the level of collaboration that we need to see to really supercharge this cancer enterprise. We need infrastructure that can allow us to collaborate.

That infrastructure is in the form of three areas. Continued support for fundamental science, for basic science, new additional, really significant support for data infrastructures, data infrastructures that allow us to collaborate right down to the individual, patient, or individual person level. The data structures to allow us to do that we do not currently have, and they need to be funded and built.

And then, last of all, we need to learn from every patient, and we need to learn from the clinical care environment. We really need to help develop an infrastructure that will allow our clinical care environment to be a research environment as well.

Nothing illustrated this more concretely than the COVID epidemic where we didn’t have the immediate data from the clinical environment like this to respond to a pandemic.

Let me tell you something else. The data that we use today to be able to analyze cancer mortality and cancer survival is already three years old before we can use it. SEER data, we’re using SEER data from 2019 because it takes that long to gather the data, curate the data, process the data, get it into the systems. That doesn’t make any sense in 2023.

MO: And it used to take even longer before that.

MB: It used to take even longer. Can we change it? Yes, absolutely.

Is it going to take significant new investment? Yes, absolutely.

So, I think COVID taught us that we need to make that investment. It’s really crucial.

I’d like to see that investment also be extended to the world of oncology, world of cancer. It’s not an either/or. It’s a one-can-help-the-other.

This is why it has to be an all-of-government approach. If we’re building a system for pandemic preparedness, we want to make sure that very same system can be very nimble, and we can leverage that to also get better data and better research for our cancer patients.

MO: And the field is primed to do that because oncology pioneered a lot of the real-world evidence framework that allowed epidemiologists and clinicians to do what was needed during COVID as well. It’s a feedback loop, isn’t it?

MB: And this is why it’s an all-of-government approach.

So, we want to be able to sit down with the CDC, which we are doing and say, wow, look, here’s what you are doing, let’s do it together. Let’s not build separate silos. Let’s make sure it’s together.

Together means things like common ways of obtaining patient consent, of making sure that patients are involved in this. It’s not being done without their knowledge and consent.

Because the other thing we’re acutely aware of is the need to really maintain trust with people. That is really key in our society right now. Trust has to be earned. And that’s continual hard work to earn that trust.

I do think in the cancer community, we are really fortunate to have a very engaged and passionate and thriving advocacy community. That’s done so much for us to be able to achieve and maintain public trust, all of our advocates.

It takes a lot to be a cancer patient. It takes a lot to take care of people with cancer. It takes a lot to devote your life to cancer research. And so, we’re also very concerned with making sure that people are supported if they choose to take that on as a life’s mission.

But we still need to do more.

And certainly, when it comes to data structures, data systems, and doing research in the clinical environment and using data from the clinical environment, having the infrastructure always be one that maintains trust is really key.

And then finally, the last bit of infrastructure that we need more of, it speaks to the clinical care environment too. We need more ability to do clinical trials. We need everybody who’s eligible to be on a clinical trial. And we need a lot more clinical trials that are available for people.

And I want to say I participated in a clinical trial as a patient. I did. I’m walking the walk. And I’m very proud to be able to do it as a patient and very grateful to all those patients who did it before me who were able to produce the data that guided my own care.

So, I just think it’s something that every patient owes all those other wonderful people who participated before us, but not every patient has an opportunity because we don’t have enough trials. And we certainly have enough ideas for everybody to be in a trial.

We just don’t have the ability to make that happen yet at a system-wide level. But we certainly could.

PG: Is there anything we missed? Anything we didn’t ask?

MB: I don’t think so. This has been great. The only other thing I always want to remember is that certainly NCI is very, very dedicated to the next generation, not only in terms of our brilliant scientists and clinicians and researchers, but all the huge number of individuals we need to support to be able to deliver care and do research.

And another thing we’ve also been challenged with recently due to COVID is an understanding that it takes a lot to be a cancer patient. It takes a lot to take care of people with cancer. It takes a lot to devote your life to cancer research. And so, we’re also very concerned with making sure that people are supported if they choose to take that on as a life’s mission.

So, that’s another ongoing, constantly evolving concern. And if you read the National Cancer Act, which it’s obvious you have, you will also see that one of the important obligations of the NCI director is to train and educate the next generation, and support the next generation to take this on.

It’s one thing we didn’t touch on. It’s definitely one of the eight goals, and it’s really important, and especially right now, because I think our healthcare and research community, like every community, has been under a lot of stress due to the recent pandemic.

PG: Well, thank you so much for walking us through this. It’s an incredibly complicated story. And I think, actually, I’m much clearer on it, and it’s nice to know how you’re thinking about this, and how you developed these ideas.

MB: I’ll throw one more at you. There’s no daylight whatsoever between the National Cancer Plan and the Moonshot. The Moonshot is the call to action and the charge at the level of the president that says, “Hey, we need to end cancer as we know it, and we all need to work together.”

The Cancer Plan is in service of that, overall. So, again, there’s no daylight between the two. The plan is how we’re going to do the things we need. It’s a tool to help us do what we need to do.