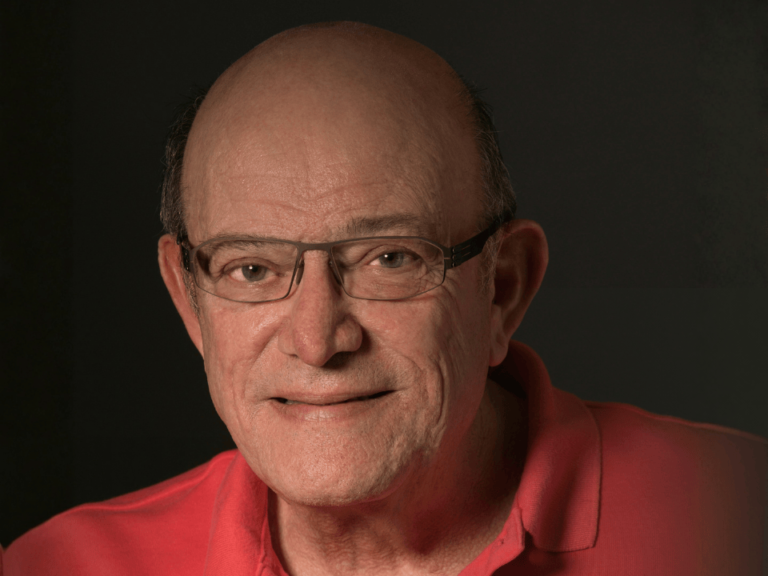

Saul Sharkis, a scientist who studied the biology of blood stem cells and how they could be used to treat cancer through bone marrow transplantation, died Sept. 4. He was 72.

Sharkis was a professor of oncology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and a faculty member in the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center for more than 40 years.

A native of New York, Sharkis earned his B.A. from Hunter College and his master’s and doctoral degrees from New York University. After completing his postdoctoral research at National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, he was recruited to the faculty of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine’s Department of Oncology.

Sharkis was among the first to isolate and study hematopoietic stem cells. His research was important to the progress of bone marrow and stem cell transplants because it helped reveal the mechanisms of engraftment. His work also uncovered the biology of stem cells, isolating and tracking a stem cell population to show that small numbers of stem cells can reconstitute bone marrow following transplant.

He also studied the plasticity of blood stem cells and developed research models to explore their capacity to develop into other cells, particularly epithelial cells in the liver, pancreas, kidney, breast and intestine. These cells line the organs and are often the site where cancers begin. His hope was that one day, stem cells could be use as cellular therapy to treat cancers.

“Saul inspired us with his dedication, invaluable knowledge and experience. He was a brilliant yet humble man, a superb scientist and a Johns Hopkins innovator,” said William Nelson, director of the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer. “He will be sorely missed by countless residents, fellows and colleagues.”

He is survived by brother, Alan, and sister-in-law, Anne, as well as nieces and nephews.