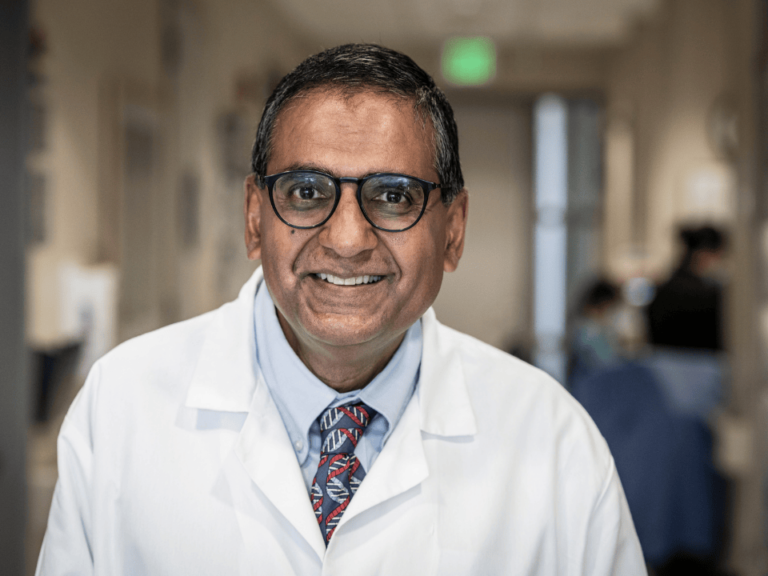

Something felt wrong during one of Morhaf Al Achkar’s regular runs on the treadmill in late 2016. He started gasping for breath.

“It became really hard to run,” he said. “That sudden development of shortness of breath alarmed me.”

Al Achkar had recently begun to work out with a trainer, as he had been feeling weaker than usual and wanted to rebuild his strength.

Being a family physician in Indiana at the time, he asked a resident at the clinic where he worked to listen to his lungs. “There’s no air moving on the left side of your chest—that doesn’t seem right,” Al Achkar recalled hearing from the resident.

An X-ray taken immediately after hinted at why. The entire left side of his chest glowed white, indicating a massive amount of fluid built up there.

A few weeks later, Al Achkar received devastating news: he had stage 4 ALK-positive lung cancer. He estimated that he would live for just another six to 10 months.

He began a treatment regimen with crizotinib and continued working at the clinic, a choice that many colleagues questioned. He remembers one resident saying, “You’re seeing patients…and you’re almost as sick as they are—what are you doing here?”

And today—nearly eight years after his devastating diagnosis—Al Achkar is still working, now primarily as a researcher and educator.

“[When] cancer became part of the picture, it struck me that my life project was going to be cut short,” Al Achkar said to Deborah Doroshow, assistant professor of medicine, hematology, and medical oncology at the Tisch Cancer Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Doroshow, who is also a historian of medicine, is a member of the editorial board of the Cancer History Project. Their conversation is available on the Cancer History Project podcast.

The cancer news came amid a time of big career changes for Al Achkar, who was 33 at the time. He had finished his residency training a few years earlier and was pursuing a PhD in education. And he had just agreed to move halfway across the country by signing a contract for a position at the University of Washington.

“I was excited for things to come in my life,” Al Achkar said. “A cancer diagnosis meant potentially abortion, or an end, for some—if not all—of those projects.”

Despite his waxing and waning energy levels from the treatment, Al Achkar continued to seek out activities he enjoyed and live life to the fullest. He even searched for love and went on dates, knowing that any potential relationship could come with a short time limit.

“Generally, we take for granted that we’re alive, and that we’ll be alive tomorrow,” Al Achkar said. “It’s not easy to plan in life when you don’t know how long you’re going to live.”

When you are aware enough to recognize that others are not [alive] because of injustices in our system…you feel like this is wrong and that something needs to be done about it.

Morhaf Al Achkar

Soon, though, he began to realize that death wasn’t imminent.

Al Achkar’s health remained steady, so he stopped questioning each night whether he would wake up in the morning. His treatment seemed to be working, too. Much of the fluid in his chest was gone, and it didn’t reaccumulate.

Over time, his follow-up CT scans began to be spaced farther apart. He realized at an appointment that he had another few months to live. Six months later, it happened again. And again.

Eventually, Al Achkar stopped living with short-term, less-than-year-long goals in mind. His mindset started to shift.

“I survived cancer, so this is in my past,” he said.

In early 2023—nearly seven years after the diagnosis—Al Achkar applied for his current faculty position, associate professor at Wayne State University School of Medicine. He began to apply for multi-year research grants, and even accepted a leadership position that he now holds as associate center director for education at the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute.

“I would not have taken this position, were I not a survivor of cancer,” he said. His shorter projected lifespan motivated him to take on a leadership role so that he can make a bigger impact with the time he has, Al Achkar said.

But he has also been transparent throughout his cancer journey. Al Achkar publicized his diagnosis early on through social media, and viewed it as a way to document his life for others to see and learn from.

Nowadays, he said, many people know about his cancer story before he even meets them.

Al Achkar wants to use his privilege as a physician living with cancer to help others. During the early days of his treatment, he could look up the latest research himself and received support from his eight siblings, who are all physicians or researchers.

But he recognizes that many people from marginalized communities don’t have such resources, which can hinder treatment. “Equity and access to information that can help the person make a decision still is a challenge today,” Al Achkar said.

In the years since his diagnosis, Al Achkar has interviewed people living with lung cancer for both qualitative research and his book “Roads to Meaning and Resilience with Cancer”. He can connect with those individuals on a deeper level, as a survivor himself.

Although qualitative researchers are often thoughtful and considerate, he said, “when you don’t have the language—when you don’t have the lived experience—you’re still treating the other as an ‘other.’”

And one of his projects has focused on the experiences of Black people living with lung cancer in the U.S. The goal is to examine the health disparities they face. Al Achkar recognizes that social injustices brought on by racism, poverty, and lack of education play a role in cancer outcomes.

“When it comes to the disparity, living, surviving while others don’t comes with a moral burden,” Al Achkar said.

“When you are aware enough to recognize that others are not [alive] because of injustices in our system…you feel like this is wrong and that something needs to be done about it,” he said.