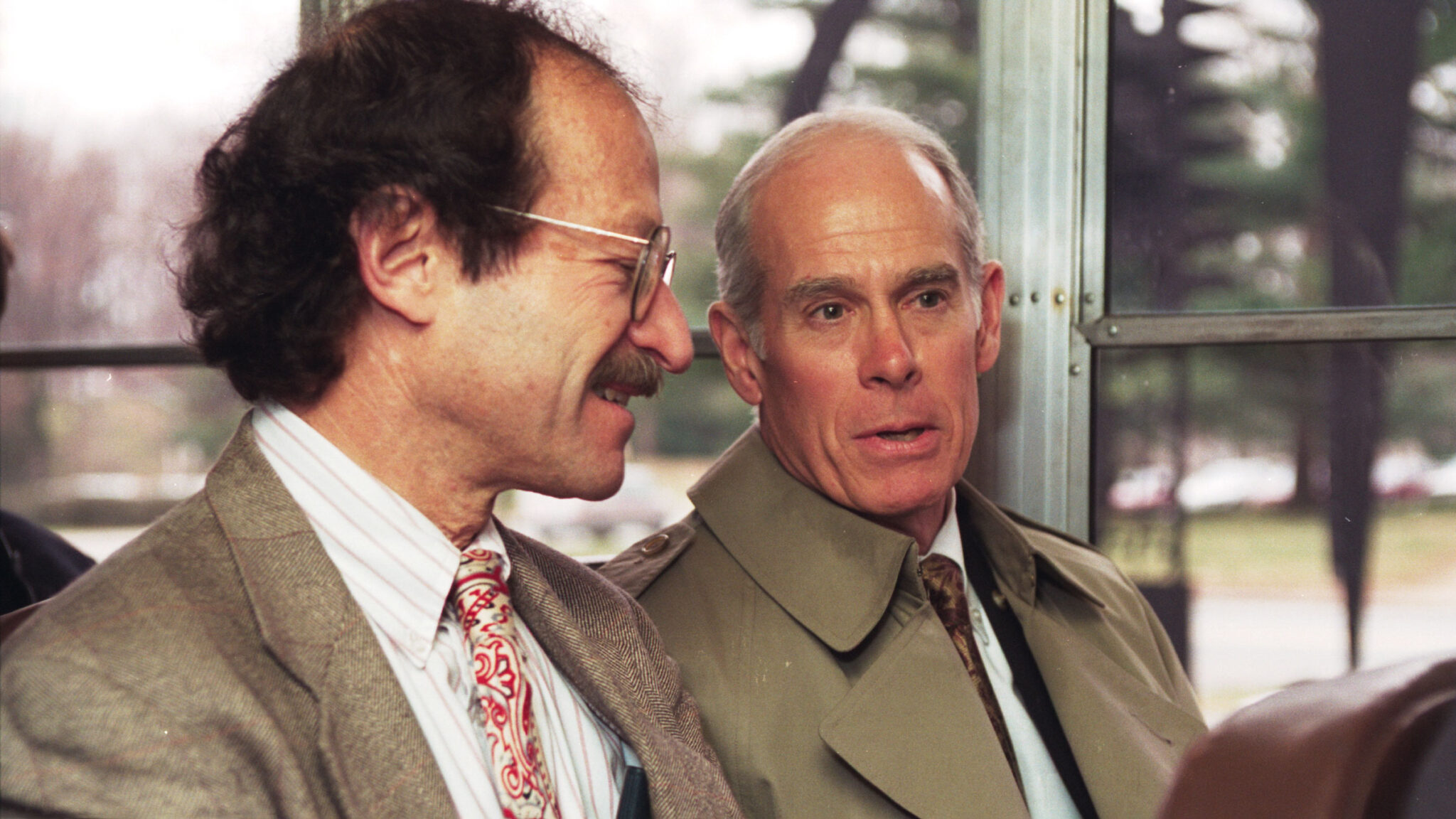

Cover: Rep. John Porter (R-IL) and then NIH Director Harold Varmus on an NIH shuttle in an undated photo taken during a day of briefings. Source: Office of the NIH History and Stetten Museum

On June 3, two days after his 87th birthday, John Edward Porter, who represented the 10th Congressional District of Illinois as a Republican for over twenty years, died of pneumonia in a hospital in Northern Virginia.

For most of the time that I was the director of the NIH during the Clinton Administration, John Porter was our “Cardinal,” the chair of the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health, and Education (“Labor-H”), a position he acquired following the Republican Party’s recapture of the House of Representatives in the election of 1994.

Despite the broad reach of his subcommittee and his own wide interests (human rights, environmental protection, international affairs, and other things), John Porter was an extraordinary proponent of federal funding of medical research. He was also my advisor and my friend.

John graduated from his hometown university, Northwestern, and then studied law at the University of Michigan—but please note that he started his college career at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, with interests in statistics and metallurgy. I believe that his ability to understand the scientific process and to think with numerical precision enhanced his performance as an appropriator, especially after he assumed the chair, giving him command of the microphone and the NIH budget.

Although the Congress was dramatically changed by the election of 1994, Labor-H was much less so. During many years of Democratic dominance in the House, the subcommittee had been chaired by William Natcher of Kentucky, a famously fierce and long-standing defender of the NIH, who built a tradition of strong bipartisan support for the agency, a founding principle that John embraced.

One notable feature of those days was the annual marathon of hearings on the NIH budget. Virtually every one of NIH’s twenty-some institute and center directors, and a few others, had a substantial share of the limelight—generally forty-five minutes on the stand—to make their case and respond to questions. This required a substantial commitment of time: two two-hour sessions a day, for three days each week, for three weeks. John was always there, sometimes flanked by his colleagues, sometimes alone—impeccably attired, politely earnest in manner, and gratifyingly attentive, inquisitive, and insightful.

Because I, too, attended all the sessions—sitting beside each of all those NIH officials, both as a show of support and as a warning not to ask for more funds than the administration had agreed to request—John and I spent a lot of time together, facing each other, reading reactions, sometimes rolling eyes, nodding approvals, or exchanging sly smiles.

Throughout the years of those lengthy hearings, John wasn’t simply doing what he was expected to do. He was entrusted with the job of carving up billions of dollars among many worthy federal agencies. But when the NIH was under discussion, it was evident that he cared very deeply about it all, and it was a remarkably varied menu.

He had to deal, of course, with the splashy stuff from the news feed—cloning Dolly the sheep, growing human embryonic stem cells, attempting gene therapy—and he asked the questions that revealed benefits, while also exploring anxieties. But he was equally curious about whatever progress the NIH had made each year against major diseases, including cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and AIDS. During his tenure, this meant hearing about new treatments (anti-retroviral therapies for AIDS, targeted drugs for breast cancer and adult leukemia), new imaging methods for heart disease, and an NIH-wide effort to understand the basis and complications of diabetes.

Large expenses always require special attention from appropriators. John’s chairmanship allowed us to make the case successfully for important expansions of our science and our facilities. In particular, he led his subcommittee to pay for the accelerated sequencing of the human genome and for the replacement of the Clinical Center and the construction of a new vaccine center on the NIH campus in Bethesda.

Beyond funding such tangible items, he was willing and able to think about less glamorous plans to change how we work—improving peer review or making scientific results more accessible.

Source: Research!America

On all these disparate fronts, his questions were consistently probing, yet knowledgeable, to the point, yet friendly. They reflected genuine interest in what we were doing. He remembered that we couldn’t do our job as scientists and administrators of science, unless he did his as an appropriator, by legislating an appropriately generous allocation of funds for NIH.

John’s commitment to a fiscally sound NIH was most evident in his role in the doubling of the NIH budget from 1998 to 2003. Several features stand out. He knew that the plan would fail if it were perceived to have a single proponent, so he engaged his fellow congressional supporters of the NIH, from both chambers and both sides of the aisle (Arlen Specter, Tom Harkin, David Obey, and several others) to become early proponents.

He also knew how to include a similarly inclined White House in the plan. The idea of increasing NIH’s budget was highlighted, for example, in Bill Clinton’s State of the Union address in January 1998. John’s modesty was a winning strategy, and inherent in his character.

A sometimes-overlooked aspect of the doubling was the pledge by appropriators to make a long-term (five year) budget commitment. Multi-year plans are, of course, more sensible approaches to the funding of science than single-year allocations, but appropriators understandably relish annual control of large sums. It was precedent-breaking for so many leaders to sign up for five years of approximately 15% increases for the NIH.

Moreover, this was a “clean” plan, with no special projects (earmarks) and no promises to individual Institutes or disease advocacy groups.

We may never know who was specifically responsible for which element of the plan, but John’s fingerprints were all over it.

John Porter the Appropriator

Last week, on June 15, a commemoration of John’s life was held at his golf club in Northern Virginia, near the place he had lived since retiring from Congress in 2001. (He left Congress at a relatively early age, he once told me, because he had reached his party’s imposed three-term limit as chair of the Labor-H committee. But he took up several roles as an advocate for medical science, while also holding a position with a prominent Washington law firm.)

That day, the club lounges were filled with John’s many loyalists—his widespread family and friends, advocates for research and health, and people who had served on his political, personal, and congressional staffs during the past forty-plus years.

Many of John’s attributes were remembered fondly—his humility, grace, clarity of thought, and firmness of purpose, even his fondness for golf. It was reassuring to hear about the many awards that had been given to him as marks of public appreciation during his lifetime.

His achievements had not been neglected, but he didn’t boast about them. They include the highest honors that can be conferred by the National Academy of Sciences, the Lasker Foundation, Research!America, and others. And a major new building for neuroscience research on the NIH campus was named for him in 2014.

John’s wife, Amy, reminded me about a private commencement ceremony that was staged for him to receive an honorary degree at Tufts University in 1997. The University President, John DiBiaggio, had asked me to talk about John on that occasion.

Source: Research!America

Source: Research!America

I recalled for Amy the rough comparison I had drawn between John Porter the Appropriator and Prince Henry the Navigator, who was not himself a navigator but served as the patron for adventurous Portuguese explorers in the early 15th century. (Recent history has shown that the comparison is not entirely apt—aspects of Portuguese exploration were deplorable—but the royal historical analogy gave John pleasure at the time.)

In his role as NIH’s Cardinal, John also served as our advisor and defender. At last week’s memorial, Francis Collins (who led the Human Genome Project during John’s chairmanship) described going to speak with him privately about threats from competitors in the private sector to place the sequence of human DNA behind access barriers and getting a positive response to the request for him to champion the public effort.

I have similar memories of John’s willingness to provide help under difficult circumstances. On one occasion, I was being squeezed politically. On one side were my colleagues who wanted to proceed with legislation to prevent ergonomic injuries in the workplace after the issuance of a thorough report by the Centers for Disease Control.

On the other was a group of Republican lawmakers who wanted to delay legislation by requiring NIH to commission another lengthy report on ergonomics from the NAS. Somewhat sheepishly, John asked me to meet with his party-mates to work out a compromise—one that may not have made anyone happy, but preserved the NIH budget.

I was reassured by John’s quiet resolve to make decisions about the NIH based on evidence and reason, not on political pressure and personal threats.

Harold E. Varmus

On another occasion, John asked me to provide a private explanation of why my proposals to make the scientific literature more accessible were not going to destroy the US publishing industry, as claimed by a former member of Congress who had become a lobbyist for the Association of American Publishers.

By allowing me to tell him about this complex business, at a length not possible in a hearing room, we avoided the political collisions that might have impeded efforts to create PubMed Central, NIH’s public, digital, full-text library.

Sometimes, our relationship was more social than political. I remember with special clarity one evening when John joined me and my spouse for dinner at a restaurant in our Woodley Park neighborhood. We learned a lot that evening about each other and how we were brought together in our improbable relationship.

But the tale that stuck with me was his account of a disease advocacy group that had been picketing his house in Illinois, demanding more funding, despite John’s advocacy for medical research and despite the struggle that a member of his family was having with that very disease.

On this occasion and others, both private conversations and public events, I was reassured by John’s quiet resolve to make decisions about the NIH based on evidence and reason, not on political pressure and personal threats. When I think about the best of my times in public service, those days in the Rayburn hearing room loom large. And John Porter is presiding over Labor-H, with humor, humility, and an informed affection for the NIH.

Harold Varmus, MD, who shared the 1989 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine, served as the NIH director from 1993 to 1999 and NCI director from 2010 to 2015. He is the Lewis Thomas University Professor at Weill Cornell Medicine and a senior associate member of the New York Genome Center.