Scientists at City of Hope, working in collaboration with researchers at Translational Genomics Research Institute and other colleagues have found that the actions of circulating immune cells at the start of immunotherapy treatment for cancer can inform how a patient will respond to the therapy.

The team’s findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

“We used an ecological population model to understand the interactions between circulating white blood cell abundance and tumor response to immunotherapy,” senior author Andrea Bild, professor in the Division of Molecular Pharmacology within the Department of Medical Oncology and Therapeutics Research at City of Hope, said in a statement.

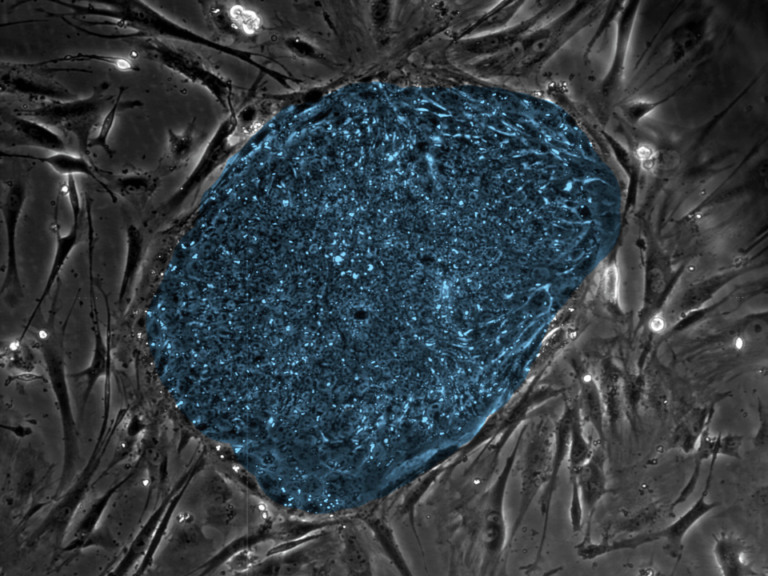

In an effort to find ways of identifying who is more likely to respond to immunotherapy at the start of treatment, or possibly even before it starts, researchers used a mathematical model developed by Bild and colleagues.

The team used the model to analyze data from the results of patients with advanced colorectal or other gastrointestinal cancers who were enrolled in a clinical trial led by Sunil Sharma, deputy director of Clinical Services at TGen, an affiliate of City of Hope. The trial involved a chemotherapy regimen followed by a combination of chemotherapy and immunotherapy. It measured the strength of patients’ tumor-immune cell interactions, which was then related to different immune cells categorized by their behavior.

The findings highlight, for the first time, an important predator-prey relationship between circulating immune cell dynamics and a tumor’s response to immunotherapy. In particular, predator T cells showed increased differentiation and activity of interferon, a protein that exerts anti-tumor effects, during immunotherapy treatment in patients that respond to treatment, said Bild. This relationship was not found in patients during chemotherapy, nor was it seen in those who were non-responsive to immunotherapy.

“The study shows that subsets of immune cells in the blood indicate how each cancer patient responded to this combination of chemotherapy and immunotherapy,” Sharma, who also is director of TGen’s Applied Cancer Research and Drug Discovery Division and one of the study’s senior authors, said in a statement. “We found, using this combination drug approach, that the body’s own immune response and its activation correlated with a higher response to the therapy among cancer patients,” said Sharma.

Next steps include further testing the ability of circulating immune cells to reflect tumor response to therapy in a clinical trial at City of Hope in collaboration with TGen.

The study, titled “Circulating immune cell phenotype dynamics reflect the strength of tumor-immune cell 2 interactions in patients during immunotherapy,” features additional City of Hope authors and researchers from University of Utah, University of Minnesota, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and University of California Los Angeles.

Portions of the work were supported by a research grant from Merck Pharmaceuticals, NCI (P30CA042014, U54CA2099780), and the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas Core Facility Support Award (RP170668).