On rare occasion, an innovator makes such a profound impact on the world that people thereafter cannot imagine what life was like before that transformation. Paradoxically, for those not witness to such an achievement, this phenomenon may have, in terms of legacy, a blunting effect.

For example, those of us who work in modern cancer centers, especially those who grew up professionally in such environments, might assume automatically that these organizations always existed in something like their present form. But this is not the case. Indeed, cancer centers as they now are, melding high-quality care with superb clinical and laboratory investigations, owe much of their invention to the vision, energy, and pugnacious perseverance of Paul A. Marks.

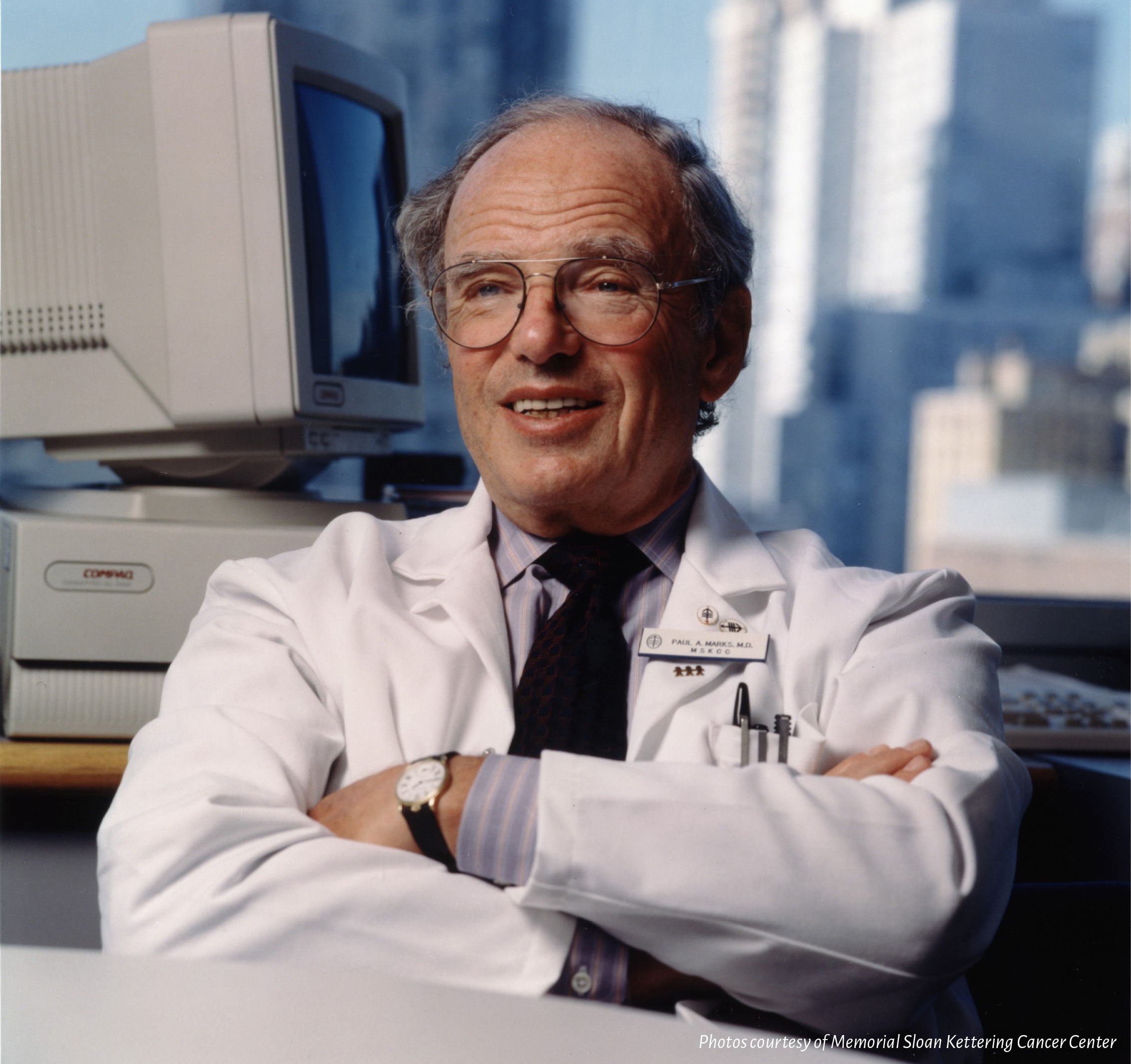

We lost Paul on April 28, at age 93, when he died of pulmonary fibrosis complicated, at the end, by lung cancer. His professional accomplishments and long list of accolades and awards is well known to the entire oncology community.

He was born in rural Pennsylvania, but spent formative years in Brooklyn, where his prodigious intelligence and legendary work ethic earned him a full scholarship to Columbia University. This led to his medical training at Columbia’s College of Physicians and Surgeons.

After productive sojourns at the NIH and the Pasteur Institute he returned to Columbia to assume increasingly responsible roles: professor, dean, VP for medical science and cancer center director.

He joined Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) in 1980, serving as president and CEO for almost twenty years. Along the way, he not only made major scientific contributions—the mutational bases for some hemolytic anemias and thalassemia and the invention, with colleagues, of differentiation therapy of cancer among them—but garnered an impressive array of honors including membership in three national academies and the Presidential National Medal of Freedom (1991).

For most academic physician-scientists, this would be more than achievement enough. But what I assert will stand the true test of history is the revolution he produced at MSK in his two decades of leadership.

My first contact with Paul was well before that, when, as a medical student at Columbia in the late 1960s, he lectured my class in hematopathology. In describing him then, formidable is much too weak a word. Large and powerful in body, brilliant and demanding in intellect, with a piercing visage, he had no tolerance for laziness or imprecision in thought or communication. Frankly, he was terrifying… but a great teacher.

And he was obviously a leader among his peers, commanding and receiving admiration and respect. It was for these reasons that I was surprised as well as gratified when at a ceremony in which he awarded honors to medical students I realized how genuinely happy he was to recognize the talents in that young crew. There was honest joy in every handshake and congratulatory comment.

I suspected then that his (sometimes) irascible demeanor was a means to an end, a ploy to motivate people to strive toward the best of their abilities, for their good as well as for the good of our noble professions.

Fast forward to 1988, the year I joined the faculty at MSK, eight years after the start of his tenure there. By then, he had wrought a miraculous change. To understand the magnitude of this, one needs to appreciate what oncology looked like to organized Medicine in the 1970s, before the impact of the National Cancer Act.

Cancer physicians other than surgeons, usually general surgeons in those days, were widely denigrated and even vilified by those who knew that radiation was strictly palliative and that medicines could never have any real efficacy except in rare circumstances.

Cancer patients with metastases were rapidly transferred out of major general hospitals to special facilities like Delafield Hospital, several blocks away from Presbyterian Hospital, as if they were lepers before the advent of antibiotics. Laboratory-based cancer research was considered second-rate at best and generally unworthy of “real” scientists studying basic, as opposed to applied, biology.

Paul saw something different. He recognized that the dawn of molecular medicine was also the beginning of a new approach to cancer, one in which fundamental discovery could translate into major advances, even cures and prevention strategies. And he realized that this would take two significant changes.

The first would be to attract the very best scientists to the field of cancer research. He was confident (one of his cardinal traits) that we needed people who could create new ideas as competently as the best minds in any other area of science and could conduct research with the same level of rigor and technical sophistication.

The second would be to bring these scientists into close communication with the best clinicians of all disciplines, both to generate relevant questions and to design clinical trials to test new answers in the setting of actual human disease.

To accomplish these tasks, he tackled MSK at a difficult moment in its history. It was just emerging from a major scandal of scientific misconduct. It housed outstanding clinicians, but clinical oncology then was largely removed from the then rapid progress in DNA science and cell biology.

While much has been written about his methods and style during this period, the fact stands out that by his simple act of melding MSK’s hospital with its research arm, the Sloan Kettering Institute, the two being separate at that time, he brought the two worlds together under effective, focused direction.

Moreover, his skill at recruitment of top talent—scientific, clinical, administrative, and board membership—and his ability to gather the financial resources necessary to allow them to do their jobs had already by 1988 made MSK a powerhouse in the field. For Paul, it was all about excellence and the fostering of dynamic, imaginative, fruitful interactions.

It is interesting in that regard that another of Paul’s passions—visual art—is also all about excellence and adventurous creativity. He would sometimes escape in the middle of a particularly stressful day to the comforting European painting sections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. (There, I amusingly ran into him once while I was playing hooky, if the truth be told.)

I remember a meeting in Paris where he and Joan skipped a festive meal, another of his passions, to see an exhibit of Giacometti sculptures. He was also quite adventurous athletically. I remember a particularly harrowing ski run down icy Les Diablerets, where we only discovered we were in forbidden off-trail territory when we found ourselves by the side of an obscure road at the bottom.

It was therefore consistent with his principles and his personality that he championed the building of the Evelyn H. Lauder Breast Center at MSK, the institution’s first off-site facility, which opened in 1992.

Bringing together all disciplines and services in a setting conducive simultaneously to compassionate and comprehensive care and inventive clinical investigation seems in retrospect to be natural. However, it was a novelty at its time, an adventurous experiment, now proven successful—as is the modern cancer center in its entirety and now ubiquity.

So, beyond his own considerable scientific achievements, his leadership of national and international efforts, and his mentorship to many generations of clinicians and scientists, his legacy lives on in the very structure of how academic oncology now operates and thrives.

We owe him much and deeply mourn his passing.

The author is senior vice president, in the Office of the President, medical director of the Evelyn H. Lauder Breast Center, and the Norna S. Sarofim Chair in Clinical Oncology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.