We asked six experts in disease prevention, nutrition, and guidelinemaking to discuss the just-published recommendations that disagree with the dietary guidelines promulgated by mainstream health organizations.

The paper, published in Annals of Internal Medicine said there is little evidence of increased risk of cancer, heart disease, and other harm from eating red meat and processed meat.

The Cancer Letter‘s coverage of the paper is available here.

The Cancer Letter reporters Matthew Ong and Alex Carolan asked all six experts the same 10 questions.

So, doctor, may I have a smoked kielbasa tonight? How about a hamburger?

Reedy, NCI: Let’s talk more about you and your overall eating pattern, as well as what makes up a healthy eating pattern. Then, you can consider how those foods may or may not work for you. Leading global cancer experts continue to recommend the guidance that existed before, regarding limiting red meat intake and eating little, if any, processed meat for cancer prevention.

Nicastro, NHLBI: I won’t physically try to stop you from eating your smoked kielbasa or hamburger. I’ll just remind you that current Dietary Guidelines for Americans encourage a healthy diet that is high in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, low and nonfat dairy, seafood, legumes and nuts, and limits red and processed meats, sugar-sweetened foods and drinks, and refined grains.

Redberg, UCSF/JAMA: These studies don’t change my advice. In general, smoked foods have some carcinogens and other things. So, you should limit your intake. If you want to have it tonight, I think once a week, once every two weeks, once every few weeks is fine. But I wouldn’t have it every night.

Daniel, MD Anderson: Well, maybe you can have one tonight, but then I would suggest not having some again for a while. I feel that we are not ready to change dietary recommendations based on a single report. That’s not how things work. Whether their report is right or wrong, it’s still one report from one group and that’s not how we make changes and decide what’s important for public health.

McCullough, ACS: Kielbasa is OK if you eat it only occasionally. One suggestion is to use small amounts to flavor a dish, instead of considering it the center of your meal. A hamburger is a fine alternative, but you should limit your total red meat consumption to a few times per week or less. Be sure to choose lean cuts, and avoid charring or burning your meat. And be sure to load up on veggies.

Harris, UNC: If you are thinking about whether these things will affect your health, we really don’t know the answer to that very good question. If you have it once, the likely answer is that it will neither help nor hurt. If you eat it regularly, we really don’t know.

If you want to know whether regular eating of these meats will cause environmental damage compared with eating vegetable protein, the answer is yes, these meats are worse for the environment than eating vegetable protein.

Is this the first time that a comprehensive meta-analysis of health outcomes of this kind—stemming from consumption of red meat and processed meat—has been conducted?

Reedy, NCI: A review by the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization was released in 2015. Most recently, in 2018, the Third Expert Report came out from the American Institute for Cancer Research and the World Cancer Research Fund. These dietary guidelines review specific questions related to dietary patterns and the role of red and processed meat. So, yes, there are other reviews of this kind.

Redberg, UCSF/JAMA: No, not at all. There have been multiple meta-analyses. We published several, and when I say “we,” I mean JAMA Internal Medicine in the last few years. I think our most recent one was from the French group NutriNet-Santé, looking at processed foods, organic food and meat consumption. That was a study, not a meta-analysis, but there have been multiple meta-analyses published, and all of them find that diets that are low in red and processed meats are associated with longer life.

Daniel, MD Anderson: It’s not the first time by any stretch of the imagination. They just did it differently. And when you use different methods, you’re going to get slightly different answers.

What’s really different about this review versus prior reviews is this group is really looking at the perspective of individual decision making, and they’re looking at broader cancer outcomes, where they’ve melded different cancers together. The way that they weigh evidence is different, and so, they’re getting slightly different answers. I’m not saying that one is a better way or one is not a better way, but they’re just incredibly different. And for cancer, I don’t find this review as convincing as others that I have seen.

McCullough, ACS: Meta-analyses similar to these have been conducted before. And I think these meta-analyses are consistent with relative risks of these various outcomes that have been shown previously. In that regard, the findings are very consistent with previously conducted meta-analyses and systematic literature reviews.

Harris, UNC: I’m not an expert in this area, though I have looked at it in some cases before, but from all I know and from all I can read, they really surveyed the literature really well. They got all the studies, they put them all together, and they are correct, I think, that the certainty of evidence of association is either low or very low.

Although the other side of the coin, as I was saying, I think what Dr. Hu at Harvard and others would say is that “Yes, the evidence is not great, but what evidence there is—and there are a lot of studies, all of which are flawed—all of them seem to show basically the same thing, with some exceptions, that there is an association.”

It’s just that we’re not real sure about it, because there could be other things that might explain that association. But consistency is one of the things that is important here.

What are your takeaways from these systematic reviews?

Reedy, NCI: The key takeaway is that we know that leading global cancer experts don’t agree with these authors’ interpretation of the scientific evidence. These are so-called guidelines.

In nutrition science, as in all areas of research, scientists examine and evaluate the literature, and produce reports where there is concurrence and where research gaps remain. In the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, nutrition experts come together every five years to review the scientific evidence and write scientific reports. Those guidelines are in process right now and being updated. But the existing guidelines haven’t changed in light of these so-called guidelines that have been released.

Nutrition experts have also reviewed the literature specifically for cancer, through the efforts led by the American Institute for Cancer Research and the World Cancer Research Fund—they published their Third Expert Report in 2018. We also have the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer’s monograph on red meat and processed meat. These reports align—the Dietary Guidelines, the AICR/WCRF Report, and IARC’s monograph.

Nicastro, NHLBI: Our takeaways are that the current United States Dietary Guidelines for Americans still stand—the overall recommendations about a healthy dietary plan of a variety of fruits and vegetables, and protein foods, etc. The guidelines are based on a high quality of evidence, and that is what we should be putting forth to the public.

Redberg, UCSF/JAMA: We already knew we don’t have a lot of randomized controlled studies when it comes to nutrition, but I don’t think that we should expect to have randomized controlled studies. It’s not reasonable when you’re talking about food, which is certainly a lifestyle, and not a drug, where you could easily randomize and give half the people the drug and half the people control.

We all eat different things, and we’re very complex. I think of food research like smoking research. To me, this reminds me of when the tobacco industry said, “No, smoking hasn’t been proven to cause cancer, because there were no randomized studies.” I mean, you just don’t need randomized studies when you’re talking about big lifestyle issues like smoking or like food.

There have been so many very large observational studies that show, convincingly and consistently, that people who eat more of a plant-based diet live longer and have better quality of life. To take that same data and then say, because “there are no randomized studies,” that we think it’s fine to eat meat every day, I think does a disservice to the public.

Daniel, MD Anderson: So, I actually would refer you to the American Institute of Cancer Research and the World Health Organization, particularly for your readers, if you want to know a group that for several decades has been putting together expert panels to go over the literature. I’m talking human evidence, observational and trial and experimental evidence; for example, how does this work in a mouse? How does this work in different types of model systems? What is the impact on the microbiome?

The AICR and WHO have two different panels that get together. One is composed of people who have expertise in human nutrition with expertise in nutritional epidemiology or clinical trials. Then they have another group that gets together who is more basic science, and together they review all the experimental evidence on each of the topics.

The other thing that’s critical to note is that these groups (the AICR and WHO) look at individual cancers and even subtypes within those cancers. So, for example, we know that esophageal cancer has two very distinct subtypes and diet is only related to one of those subtypes. And they look at that level of detail at the literature and at the evidence before they make their statements and conclusions.

McCullough, ACS: As I mentioned, these authors actually confirm what’s been reported before in terms of the relative risk. They also present the evidence based on the risk difference. The risk difference for cutting back on or limiting red or processed meat may appear small for some of these outcomes. For others, it’s really how you interpret it.

But while they might seem small for some of these outcomes, for individuals who eat a lot of meat or might have a family history of a particular outcome, it might have more of an impact.

What they’re saying is that on an individual basis, if an individual is to look at this and say, “How much can I lower my risk of different outcomes, would this make a big difference for me?” For some, the risk difference on an individual level is small.

In the example I cited before, the authors estimated that the lifetime risk of dying from cancer was 105 per 1,000 people, that number goes down to eight fewer with lowering processed meat intake. So, instead of 105, it would be 97.

Regarding Table 2 in their paper on cancer mortality, an individual could look at this and say, “Well, my lifetime risk is already 105, but if I cut back by three servings of processed meat per week, then that would be 97.” For an absolute risk difference, that’s how it translates for an individual. Individuals could weigh this information to decide whether it’s really worth it for them to limit their intake.

But in addition, these authors also published a narrative review on a summary of studies that have looked at people’s meat preferences, and whether they would be willing to cut back on their meat intake. And they concluded that omnivores would be unlikely to want to cut back on meat intake. In their recommendations, they considered that people are unlikely to change their habits.

Harris, UNC: There are a couple of things that are important in writing about this. Make sure that you keep two things separate. One is the certainty of the evidence, and here, it’s the certainty of evidence of association. Whether or not that association is causal or not is a separate question, but the certainty of evidence of association is the first issue.

The second issue is the magnitude of effect. And that magnitude of effect may be looked at in absolute terms or relative terms. Usually, people look at it in relative terms if they want to make it look big, but absolute terms, I think, would be more informative.

What these folks have done is five systematic reviews, and these are very good people, let me just say. These are not rookies or amateurs. These guys know what they’re doing. So, they have done an exhaustive search of the literature with thousands of papers. I mean, we do these systematic reviews ourselves here at UNC for the [US Preventative Services] Task Force, and it takes us 18 months. It looks like it took them several years to do this. And I’m not surprised. And so, they’ve done an exhaustive search of literature, and they have looked at, first, certainty, they say, for almost every category, except for people’s opinions.

The other systematic reviews find either low or very low certainty. That’s not uncommon in systematic reviews. We often see that. So, we, methodologists, look at evidence fairly critically these days. And so, it doesn’t look like the evidence is very certain about whether there’s an association or not. If anything, it falls on the side of association. It’s just that the evidence is not real good about that association.

But, in all fairness, I think the people like Frank Hu at Harvard, they would point out that it’s pretty consistent that it is a positive association. It’s just that the evidence is not real strong about that.

And that has to do with all kinds of methodologic problems with nutritional epidemiology, which we can go into, if you want. But other people have talked about that before—unmeasured confounders and whether measurement itself is good, and whether the time is adequate to look at these things.

Are the conclusions presented in these systematic reviews consistent with what you know about evidence on the association between consumption of red and processed meats with cardiometabolic and cancer mortality outcomes?

Reedy, NCI: The authors have really created a big splash, and unfortunately, it’s leading to a lot of confusion. We see that these new so-called guidelines aren’t justified, but keep in mind, these so-called guidelines are also contradicting the evidence that was generated from these authors’ own meta-analyses.

They have five published systematic reviews, and in three of these meta-analyses, they’re reporting similar findings as other reviews on red and processed meat and increased risk for specific health outcomes. These studies are all finding that a lower consumption of red meat and processed meat is associated with the reduced risk for all cause mortality, for cardiovascular mortality, for cancer mortality, and for Type 2 diabetes.

Nicastro, NHLBI: The authors’ recommendations from the meta-analysis were considered weak recommendations in citing low certainty of evidence. So, this suggests the authors are equivocal in their recommendations. The recommendations also were not unanimous in the paper.

Current Dietary Guidelines in the United States draw from the same body of evidence that these researchers of the meta-analysis had available to them. The difference is that the guidelines look at dietary patterns or eating patterns as a whole and conclude that a reduction in red and processed meat would be beneficial. The authors of this analysis looked at red and processed meat in isolation.

Redberg, UCSF/JAMA: The evidence here, to me, says the same as all the evidence I’ve read in the past, that there is good epidemiologic data to suggest that there is better survival with less meat-based diets. I think what they’re saying is that the quality of the evidence is low. But as I said, I don’t think that you can expect to have randomized trials when you’re talking about nutrition.

Besides, there have even been nutritional trials like the Lyon Heart study and the PREDIMED study that looked at a Mediterranean diet versus a low-fat diet. I think that, in those cases, they were low-fat diets, and found health benefits. There have been some randomized studies for eating habits. Those are definitely fewer, as I said, but I think that’s because it’s very hard to randomize people. You can’t put people in a lab and expect they’re going to eat a prescribed diet for any period of time. It’s not reasonable.

Daniel, MD Anderson: This is not more compelling than other evidence I’ve seen. I mean, like any academic, I’m very interested in how people are looking at something in a different way. I think this should definitely be an academic debate.

I think we as scientists look at each other’s work and say, “Oh, what method are you using? What are you doing? How’d you come to this conclusion?” But this should not directly change how we advise the public. I’m interested in it as a scientist. I read it, I found things I like about it and things I don’t like about it, including things I think are missing, and things I think are thought-provoking.

But it doesn’t change several decades of research that I have personally done, and that my colleagues have done, and that we have discussed, and we have viewed. We have understood the mechanisms behind how meat promotes cancer.

This study does not change the way I feel about what I would tell the public, about what they should do to reduce their risk of cancer. It does not change that.

McCullough, ACS: The relative risks that they show are actually quite compelling and supportive of current guidelines. The difference is that they present the risk difference over the lifetime of an individual of cutting back or of limiting red meat or processed meat. These risk differences for their likelihood of getting these diseases over their lifetime may seem small.

For some of them, and myself, if I were to look at those overall cancer mortality numbers, I would actually say, “Huh, well that doesn’t seem that small to me.” For rarer outcomes, absolute risk differences appear quite small. If your lifetime risk of getting gastric cancer is 14 per 1,000 people, and it would go down to 12 per 1,000 people with lowering processed meat intake. If I were presented with these statistics, I would say, “Well that’s a way to cut back on my risk.”

But the authors’ argument is that these associations are really too small to be of benefit to individuals. And they also graded the evidence using a grading system that is typically used for pharmaceutical trials. In reviewing the evidence for diet and lifestyle, we tend to use different review criteria, because it’s really difficult to do long-term trials of diet and cancer.

It’s almost impossible, for example, to study the impact of increasing red and processed meat in cancer outcomes, because of practical and ethical reasons. There has been some question as to whether these review criteria were appropriate in this setting to study meat and long-term outcomes like this, which are typically not amenable to randomized controlled trials.

As a result, they rated the quality observational studies as weak or very weak. Maybe this is getting into the weeds, but they would downgrade the evidence if there weren’t repeated measures of diet during the course of a prospective analysis. And they would downgrade if, for example, family history was not included in the model.

Some have argued that the criteria are inappropriate for studies of diet and long-term health outcomes. They graded the evidence as weak, which is why, combined with some small risk difference and combined with their examination of meat preferences, they came to the conclusion that people should continue to do what they do now.

I find their relative risk compelling. It’s informative to have the risk difference calculated. I don’t find their argument and conclusions compelling, because of the reasons I just cited, because of the criteria that they graded the prospective studies on.

I don’t agree with their recommendation. The title of their paper is, “Unprocessed Red Meat and Processed Meat Consumption, Dietary Guideline Recommendations…” It wasn’t clear to me whether they were actually posting guidelines, or if they were saying “we recommend that guidelines do this.”

Harris, UNC: When discussing the magnitude of association between red and processed meat consumption and all-cause mortality and adverse cardiovascular outcomes, the magnitude of association would not be small, it would be certain.

If you’re talking about evidence, you need to talk about certainty. If you’re talking about magnitude of effect you need to talk about how small the size. So, don’t talk about small when you’re talking about the evidence. You’re talking about certainty when you’re talking about the evidence, and you talk about small when you’re talking about magnitude. Just be sure you got that straight.

You’re trying to inform and help people understand, not only this time, but also future times, because, remember, the issue you brought up here is a pretty common issue. This comes up with physical activity, prevention of lower back pain, seat belts, screening for diabetes, screening for glaucoma, screening for hepatitis C.

Those are all issues in which we’re talking about, “Is the evidence enough to make a recommendation?” And that’s really where we are with this. Is there enough evidence here to say anything other than, “I don’t know”? The third issue here has to do with what you should make a recommendation on.

The second part is the magnitude of effect. And I think, again, they’re correct in that the absolute magnitude of effect, if there is a magnitude—so, remember that if we have really lousy, lousy evidence, we can’t say what the magnitude of the effect is, because we don’t have the evidence to say anything, or provide any recommendations or guidelines.

Assuming that all of that evidence that we have—even though it’s low or very low certainty—assuming that that’s correct, then the magnitude of effect is, in absolute terms, small. Or even very small, or in a few cases, non-existent. And so, I think that’s real clear, too, from the evidence.

Are these guidelines coming from researchers and scientists that the public can trust?

Reedy, NCI: This was a self-appointed panel, and I know that we’ve heard from other reports that there is some disagreement among the authors. Not all the authors agreed with the language and the final papers.

Redberg, UCSF/JAMA: I don’t know the team, but I assume this manuscript underwent peer review just like any other manuscript would in a high-quality medical journal like Annals.

Daniel, MD Anderson: I don’t know them personally. They’re not the same cohort of nutritional scientists that that serve on the AICR. I don’t know enough about them to make that kind of assessment.

McCullough, ACS: Different experts can look at the same data and come up with different conclusions or recommendations.

Harris, UNC: All of us have inherent biases built into us. And so, it’s never true that we’re not influenced by our own prior ideas about these topics. And these people, like all of us, have prior ideas about them. And so, clearly, they’re influenced by those, but there’s no financial gain, as far as I can tell.

The best way to deal with that problem with prior thoughts and prior opinions is to be explicit and transparent. And I think they have done that. They’re explicit about what they did and they’re transparent about their methods. And so, I think that’s all good. I don’t think there’s a lot of debate about the certainty part.

Is this the right context for a conversation about thresholds for evidence-based guidelines? If the evidence is of low certainty or very low certainty, and the effect is small or nonexistent, should the investigators be saying, “We really don’t know,” instead of recommending, “Maintain your intake”?

Reedy, NCI: It’s really important to look at the total diet in order to provide the best dietary guidance. This concept of a healthy eating pattern, the total dietary pattern, is a guiding principle that we see in the work of the nutrition experts who are part of the dietary guidelines committee, the AICR/WCRF reports, and also among other leading global researchers. It’s clear that there can’t be guidelines for one aspect of the diet without considering what that means for the rest of the diet. We know these pieces are all intertwined and interconnected.

Nicastro, NHLBI: I think the Dietary Guidelines are still appropriate. Remember, this is one study making one conclusion. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans consider a very broad body of evidence and draw conclusions based on that data using rigorous methodology.

Redberg, UCSF/JAMA: I think it has been clearly established from multiple large-scale epidemiologic studies that there is a health benefit, a cancer benefit, cardiovascular benefit, and survival benefit associated with plant-based diet.

Daniel, MD Anderson: I want to make a couple points. One point is that the effect of diet on cancer and cardiovascular disease is cumulative. So, you asked me your first question about whether to eat a kielbasa tonight. Well, you’re not going to impact your cancer risk that day, with that decision. However, again, looking back at mechanisms like DNA damage and inflammation and the impact on the microbiome, we can see that within a day, or a month. We can’t see whether or not you’re starting to grow cancer for some time.

Flawed or not flawed, the reality is, large epidemiologic studies are the best way to look at those long-term effects. And we take into account research from those long-term observational studies, experimental studies, and trials with the intermediate outcomes. We take that all together, and we make a general conclusion.

The other thing would be that, again, they use a different method. The way that they weighted each piece of evidence is going to result in slightly different answers than the way someone else weighted the evidence. The results are not new, just the magnitude of what they’re focusing on is slightly different than what you get when you look at the whole picture. But it’s not that they did something wrong, it’s just they did it the way that they chose to do it.

They were focusing on the perspective of individual decision-making, not on public health recommendations. That’s incredibly important to make that distinction. So, they had a different purpose going in, and so, they took a different approach. Again, in my mind, taking that approach doesn’t mean that we should change the dietary recommendations for health. You know, people may not want to give up smoking. Does that mean that we should stop telling everyone to stop smoking? No.

That’s an interesting thing to think about when we think about policy decisions or what challenges we’re going to have in our approach to enacting those public health recommendations, but they don’t change whether the evidence is there, and whether that recommendation should be made.

I’ve worked on studies where we’ve actually found fairly large effect sizes from eating red and processed meat with large prospective studies. It’s individual to the cancer. In colorectal cancer, we’ve seen very large effect sizes. In breast and prostate cancer, we see lower effect sizes, because they’re totally different cancers that develop from totally different mechanisms.

So, if you mash it all together, the low ones and the high ones, you’re going to get something modest. But that doesn’t mean that red and processed meat does not cause colorectal cancer. From a mechanistic standpoint, it does.

McCullough, ACS: I think we have to have a conversation about which methods they used to evaluate the evidence for lifestyle behaviors. As I mentioned, the methods they employ here really downgrade the evidence of any observational studies, and in this case, prospective cohort studies.

Currently, other major organizations that review the literature, for example, the World Cancer Research Fund and the American Institute of Cancer Research, use different sets of guidelines.

Oftentimes, the best data that we have for evaluating lifestyle and cancer outcomes, for example, is using large prospective cohort studies.

Harris, UNC: My answer to that is that’s the issue of what we call the thresholds. There are several thresholds in evidence. One threshold has to do with how much evidence you need, how sure you have to be, how certain you have to be before you make any statement, before you make any recommendation.

Let me point out that’s the reason the US Preventive Services Task force has what they call an “I.” They’re one of the only guideline groups that have something called an “I”—insufficient evidence—that means we looked at the evidence as hard as we could. And guess what? This doesn’t answer the question that we wanted to ask.

We are not ready to change dietary recommendations based on a single report. That’s not how things work. Whether their report is right or wrong, it’s still one report from one group and that’s not how we make changes and decide what’s important for public health.

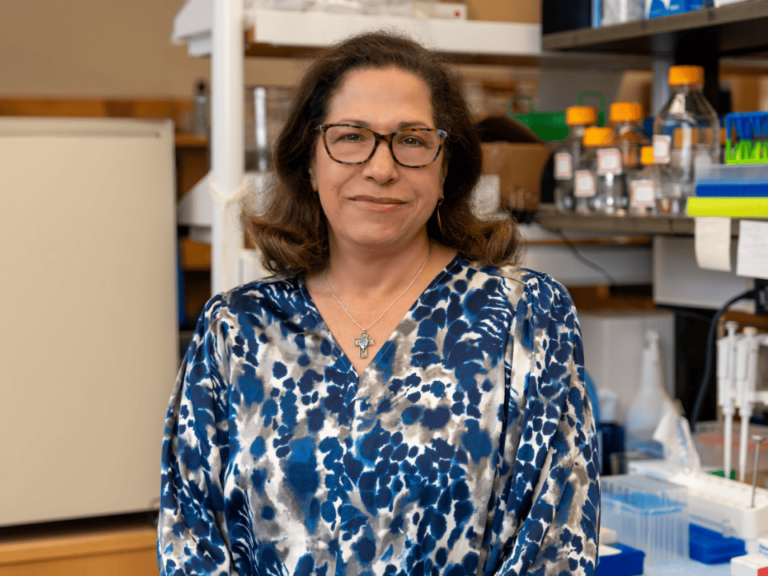

Carrie Daniel-MacDougall

And so, therefore, what we’re going to say is, “We don’t know the answer.” If you look at most other professional groups, the American Cancer Society and a whole bunch of others, they all say, “Well, you know, the evidence is really lousy here, but we’re going to give you, basically, our opinion, our thoughts about it anyway.”

In the end, you’re not sure where this recommendation came from. Did it come from somebody’s prior beliefs, like we talked about before? Or is this really something the evidence is real clear about? And so, I would say that, especially looking at it here, that the prior recommendations have been way too certain.

They have told us that we should not eat much red meat, processed or unprocessed, and that that’s bad for our health. And they came on way too strong given the evidence. That’s basically what these folks are doing. They’re calling the bluff of the previous recommendation statements, and they’re right to do that.

Those statements were based on, at best low-certainty or very-low-certainty evidence. The problem is that then, the authors go right ahead. They make the wrong recommendation. They make the same mistake, to me, that others made before. And so their statement, I’m reading this verbatim, “the panel suggests that adults continue current, unprocessed red meat consumption.” They have a weak recommendation, based on low-certainty evidence. Similarly, their panel suggested adults continue current processed meat consumption. Well, that’s different from saying, “We don’t know the answer.”

What they could have said is, “The evidence is insufficient.” They could say, “This evidence is so lousy that we can’t tell you whether eating meat is bad. Certainly, there’s no signal here that it’s good for you, by the way. But we can’t tell you whether it’s bad for you or not. So, you’re going to have to decide this based on other things.”

Are the studies methodologically sound?

Reedy, NCI: There are a lot of concerns with different things that are going on. A key point here is that we see the authors reviewing existing literature. There’s nothing new here that they’re looking at, and they’re observing similar results as other reviews have. They’re applying a different metric to those results, and they’re inferring something different from that.

Nicastro, NHLBI: They ask the question of comparing high to low intakes of red meat, and they put higher weight on randomized controlled trials. Of the 12 randomized controlled trials they have, one contributed most of the participants. About 80% of the participants came from the Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial, and that trial did not advise participants to decrease or increase red and processed meat intake. They instead asked people to lower dietary fat intake in the intervention group, compared to the control group.

And that’s true of most of the 12 intervention or clinical trials included in the analyses, as they weren’t clinical trials specifically designed to address differences in meat intake. And, in fact, they state very clearly, out of the 12 studies, none of them achieved a gradient of more than a serving per week difference in red or processed meat.

So, elevating this evidence doesn’t necessarily make sense in this context.

Daniel, MD Anderson: I do not want to comment on whether these individuals had made all the right decisions or not, because this is science, and we all take approaches, and we need to break paradigms, and that’s part of our job.

However, the problem is, when we are acting as scientists, the public perception is that we can’t come to a consensus, or we don’t know anything, or we change our mind every day. And that’s not the truth. The professional consensus, as you probably have noticed, has not changed.

I think everyone has the right to look at things with a different method. It doesn’t mean that one is better than the other, but we shouldn’t change our professional consensus on one group’s attempts or one group’s approach.

McCullough, ACS: The authors grade the certainty of evidence as low or very low in part because of the potential for residual confounding in observational studies. They did not consider dose-response relationships, and in their abstract consider recall bias a limitation; however, for prospective studies, recall bias is limited, because diet is assessed before diagnosis.

It’s impossible to conduct randomized trials for every diet question. Smoking, diet, physical activity, alcohol and body weight, all of these known risk factors for cancer and other outcomes are very difficult to test in a randomized controlled trial setting for reasons of cost and practicality, and in some cases ethical issues.

There are other modified grading systems that have been applied for observational studies that have been employed by both the USDA and the World Cancer Research Fund, where they consider the consistent findings across multiple cohorts, large numbers of participants, long duration of follow-up, low dropout rates and dose response relationships.

Of course, most guidelines also consider supportive biological mechanisms, and also randomized trials, when available. A lot of times in randomized trials—though it’s not always practical to study cancer outcomes using a randomized trial—randomized trials of potential mediators of cancer, such as inflammation, or mediators of cardiovascular disease, such as blood lipids or blood pressure, can also be considered in making recommendations.

The authors found 12 eligible trials to look at meat intake and cancer, and cardiometabolic outcomes. The authors’ own conclusions were that there were a few trials where they were able to really look at differences in red meat consumption, but the trials, for the most part, were of other dietary questions. The authors note these limitations.

For example, the only trial of cancer outcomes was the Women’s Health Initiative. That was a low-fat trial. They didn’t specifically have people cut back on meat. That wasn’t the main objective.

Because they weren’t directly looking at changes in meat in the trials, they actually did downgrade the level of the evidence. They weighted the trial data poorly as well. They said that the evidence from randomized trials was that diets lower in red meat may have little or no effect on all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease and total cancer mortality, but they had limited evidence with which to make these conclusions.

There is an inverse association for total cancer mortality in the one trial, but it’s not statistically significant. Essentially they say, ‘We did not see that the trial data shows an association of red and processed meats with lower risk of outcomes either.’ They also acknowledged that the evidence is low to very low certainty.

It’s also not clear from their summary of the trials what the original study outcomes were.

Basically, for mortality outcomes, they based it all on the Women’s Health Initiative. For cancer, the evidence was rated down to very low certainty, owing to risk of bias, imprecision or serious indirectness, meaning that the study wasn’t designed to study the effect of lowering meat intake.

Harris, UNC: I think they did the best they could. I mean, remember that these things are hard to measure. There’s not a blood test you can do that will tell you “Is this processed or unprocessed meat?” And by the way, that’s going to change from the time you’re 25, until the time you’re 35, until the time you’re 55. And then the outcomes start happening when you’re older and you’ve been changing and back and forth for many years.

And so, this is a really hard thing to study, and I think they did the best they could. I wouldn’t fault the reviewers for the deficiencies in the literature. It is true that there are these deficiencies in nutritional epidemiology, but that’s not their fault. They’re simply trying to put together all these studies that have been done, faulty as they are, and say, can we make any sense of this?

Validation has to do with replication, but that’s what systematic reviews are about. See, these folks didn’t actually follow a cohort of people. Their subjects are the studies themselves. So, they are sampling from the universe of studies, not from the universe of people. The studies have sampled from the universe of people.

The question you should be asking then, for replication is, “Did they sample fairly from the universe of studies?” The issue of replication would be, if they had found that one study found one thing and another study found something wildly different, and the third study found something even different again, then you would say it’s not replicable. Either they’re not studying the same thing or whatever the first study got is not being replicated in the other study.

What these guys are doing is looking at that issue of replication. Did all these studies agree or disagree? I’m sort of making a generalization here, but they’re finding that there’s a lot of agreement among these studies. It’s just that all of them are flawed in certain ways and so, that’s why the certainty is low.

The evidence is flawed, because of all the problems with nutritional epidemiology that we just talked about. It has to be over time, it has to measure processed versus unprocessed meat, what people are eating now versus what they were eating 30 years ago, and then, we don’t know what they replaced the meats with if they stopped eating meat. There are all these problems with this kind of study.

When evaluating food and dietary patterns, does it make sense for the investigators to assign more weight to results from randomized trials over observational studies?

Nicastro, NHLBI: While randomized controlled trials are the gold standard, these weren’t randomized controlled trials designed to answer the questions that the authors are asking.

They included 23 cohort studies, which do not involve randomization. In general, we do place more weight on randomized controlled trials, but again, the randomized controlled trials identified for this analysis did not all seek to answer the question about lowering intake of red or processed meat.

Daniel, MD Anderson: It’s true that randomized clinical trials are the gold standard. However, the kind of trial that people want is impossible. We cannot get individuals to leave everything in their diets the same and just change meat intake and follow them for 10 years to see who gets cancer.

The other problem I have whenever this stuff comes out is this reductionist approach and focusing on one food. We do not make dietary recommendations based on one food. If you read the dietary recommendations, there is substitution, there are multiple components. It’s an entire dietary pattern.

Redberg, UCSF/JAMA: I’m very much a believer in evidence-based medicine and in high quality science. But I don’t think that we should be applying those same standards when we’re talking about what people eat and food research. For that reason, I don’t think that we need to weigh randomized trials more highly when we are talking about food research.

I think perhaps that’s why this group of authors had a different interpretation, because for some reason, they decided that nutrition research and food recommendation should be held to the same standard that we would hold drug or device studies. I just don’t think that is a reasonable presumption. I don’t subscribe to it.

McCullough, ACS: It would be very difficult to conduct randomized trials of red and processed meat because of the long duration, for practical reasons, and for ethical reasons. In this case, observational studies were given a weak rating, or low certainty of evidence because of the fact that they’re observational.

We have other criteria for examining the observational evidence, including consistency of findings across studies and evidence of dose response relationships. The other organizations that typically review this type of data have been considering these criteria.

I mean, it would be great if we could do randomized controlled trials on all things that we believe influence health outcomes, but that’s not feasible and trials have their own sets of limitations.

I don’t think that these studies necessarily change the way we interpret the data. The absolute risk difference is small. We’ve known that for some outcomes and some exposures, but for some individuals it will have more of an impact.

When you look at the population-wide associations, they can have significant impact.

As far as physicians are concerned, it’s important to inform patients of existing guidelines. I don’t think that this latest set of findings should change what the guidelines are.

I don’t think it changes our recommendations, and also I think physicians can have that discussion with patients that these are the recommendations. The absolute risk for some outcomes is small, but it’s important to consider a patient’s current diet and clinical risk profile.

Harris, UNC: Now remember, what all the studies are looking at—the one randomized trial that they looked at with Women’s Health Initiative, all the observational data would say that what they’re looking at are people’s reports or, in some cases, better measurements, like health diaries and such about what they’ve eaten over time.

But people’s diets, (a) don’t stay the same all the time, (b) they don’t report them exactly correctly as we would like them to and (c) if they don’t eat meat, we’re not really clear about what they do eat in place of the meat. And so, there are time problems and replacement problems and measurement problems and all those. And so, that’s the evidence that they’re looking at. Flawed as it is with all these problems attached to it, that’s just the nature of the beast with nutritional epidemiology, as others have pointed out. So, it’s a problem.

But at any rate, if we think that what they’re looking at is important and really gets at the question we have—which I’m not sure it does—and the absolute effect is smaller, very small, or occasionally nonexistent, those are the first two parts of this.

The one randomized trial, the Women’s Health Initiative, that they talk about—they looked for all other randomized trials, and it’s pretty hard to do a randomized trial, as you might imagine, you’d have to randomize people to those who eat a whole lot of meat and those who don’t eat much meat. And people are not very good at following what they were told to do anyway. Then, you have to do it over a long time. And this study really only had people changing their habits for six months to a year, or something like that.

So, you might imagine all the problems with observational studies, but there are also problems with randomized trials, because one, people don’t adhere to what you asked them to do. Number two, you have to do it for a long time, which this study did not. You have to have a whole lot of people, and you have to follow them for a long time.

With nutritional epidemiology, not only are observational studies a problem, randomized trials are a problem, too. The fact that the Women’s Health Initiative didn’t find much after just having people change their diet for a year or so, it wouldn’t be very surprising to many of us.

I mean, it’s not a very strong intervention, which would be quite different from certain groups of people who eat very little meat for their entire lives. That would be a very different kind of intervention. But of course, they’re not randomly assigned.

While no one is suggesting increasing consumption, should these new recommendations supersede or inform previous guidelines, which suggest limiting or reducing consumption?

Reedy, NCI: These so-called guidelines that they report shouldn’t change our current recommendations on diet and disease risk. The recommendations that we have in the literature that underpin guidelines that currently exist are based on clear evidence looking at including things like randomized clinical trials with cardiovascular disease and risk factors related to cardiovascular disease.

We also have longer-term observational studies looking at cardiovascular disease and cancer, Type 2 diabetes and mortality. Our guidelines here remain the same regarding dietary patterns that are high in plant-based foods like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean protein foods, and low in added sugars, saturated fats, sodium, sugar-sweetened beverages, and red and processed meats.

Nicastro, NHLBI: The Dietary Guidelines for Americans still stand.

Redberg, UCSF/JAMA: Oh, absolutely not. No, I would not change the guidelines based on these studies. Obviously, this wasn’t any new data. It’s a different way of looking at the data and saying that food recommendations should be based on randomized studies. I don’t subscribe to that premise.

I have read many, many large epidemiologic studies and meta-analyses over the last 25 years that also are consistent in finding that people that eat less red meat and less processed meat live longer and have less cancer and heart disease. It would be hard to see how this different interpretation of the quality of evidence required for future research could be used to change the guidelines.

I don’t think there is any kind of widespread consensus that we should be doing randomized trials for food research. There’s widespread consensus that epidemiologic studies work for food, and to some extent for physical activity as well, which is another lifestyle. For smoking, I think we’ve all accepted cigarettes are a cause for cancer, and we didn’t have randomized studies to prove that.

Daniel, MD Anderson: I don’t think the evidence about red and processed meat and cancer is insufficient. I think that there is a long history of research in this area that even is outside of what we discussed.

Meat is just one line of the dietary recommendations, but it gets a lot of attention. So, you can’t completely change your risk profile by just moving meat up and down without changing other components of your diet. And I think something in the paper that was sort of buried was the dietary patterns that are traditionally lower in red and processed meats, like the Mediterranean diet. The Mediterranean diet has been associated—in several studies and trials—with lower risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease.

We need to focus on what the dietary recommendations actually intend to do. They want you to eat less red and processed meats and instead, they want you to choose fish, lean protein sources and vegetable protein sources like beans and legumes. If you do all that in its entirety, you will lower your cancer risk. If you fixate on whether you can have a steak tonight or not, you’re not going to get very far.

Those recommendations have been fairly stable for the past 40 years, and there’s a reason why. The evidence does not fluctuate that much. Like I said, we have to take this as one set of publications dropping into a giant bucket of other publications. And when you drop it into the whole mass of evidence that’s there, usually that is not as dramatic as you think it is.

Our job is to do our best to cure and prevent cancer. And that’s not the purpose of this review.

McCullough, ACS: No, I don’t think these findings should supersede existing recommendations that have been vetted by panels of experts in nutrition and cancer.

As far as what physicians should say, physicians should say that public health recommendations are to limit intake of red meat and processed meat. You don’t have to eliminate it. We don’t have to eliminate red meat, but cut back on intake levels.

The American Cancer Society doesn’t have a specific cut point for red meat or unprocessed red meat, because the evidence shows a linear positive association with more meat intake. So, it’s really saying that the more you cut back, the better. Red meat has some redeeming value. It has B12, zinc, iron and high quality protein.

We recommend that people who do eat red meat choose lean cuts and limit their consumption. The World Cancer Research Fund and the American Institute for Cancer Research recommend unprocessed red meat no more than three times per week. And that’s in the context of the whole day, including breakfast, lunch, or dinner. And then limiting processed meat to eat it only occasionally, if at all, because processed meat was classified as carcinogenic to humans according to the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization.

This wasn’t any new data. It’s a different way of looking at the data and saying that food recommendations should be based on randomized studies. I don’t subscribe to that premise.

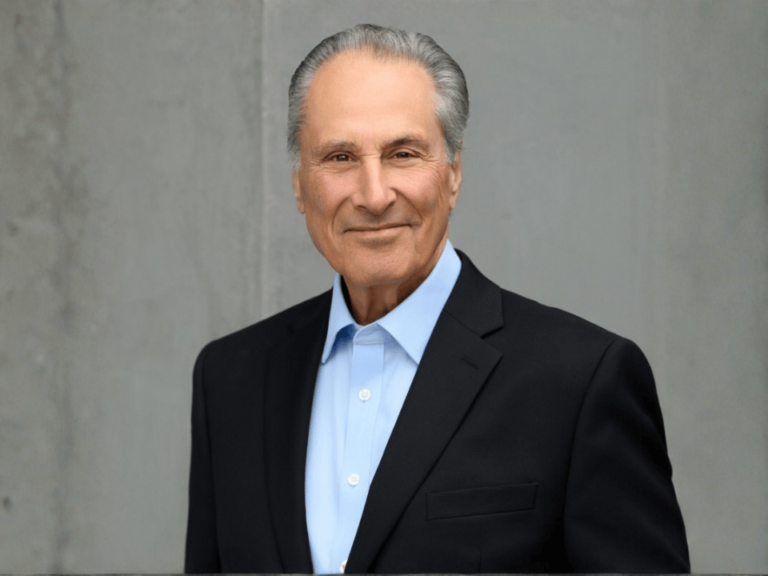

Rita Redberg

And the panel of 22 international experts considered the evidence from observational studies as well as mechanistic data from in vitro, animal and human studies. They also classified red meat as “probably carcinogenic to humans.” Both classifications were based on evidence for colorectal cancer.

For that reason and the totality of the evidence, largely from prospective cohort studies, we recommend people limit red meat and processed meat intake. My opinion is that if the physician is talking with the patient, they could let them know that these are public health recommendations based on evidence from large studies and mechanisms that have been reviewed by international panels and large health organizations.

I think the authors are to be commended for their very thorough systematic literature review and their contribution of summarizing the individual risk differences. I think that’s informative. However, what it really comes down to is the grading system applied to lifestyle factors. If we consider that all observational studies will be ranked as insufficient, or most would be, then we would not be telling people to do anything different.

That’s may be a bit of a broad statement, but I think that would be irresponsible, because we know a lot from observational studies and from these very careful comprehensive reviews of the literature that have arrived at these guidelines. We could really do a disservice to the public if we ignore all of this evidence.

Harris, UNC: To me, they made the same mistake that they’re calling others out for having made. That’s an error. When I was on the USPSTF, the way I would have voted if this had come up for us, I would have said, “This is insufficient evidence. It’s a good question, but I don’t know the answer. You should make your decision based on other things.”

I think it might’ve been controversial either way. This is just a tough issue. They’re calling out some people for past recommendations.

The recent study is of concern, because the public could interpret this as an actual new guideline. In reading these papers, it’s important to look across that totality of evidence and understand how current evidencebased guidelines are developed.

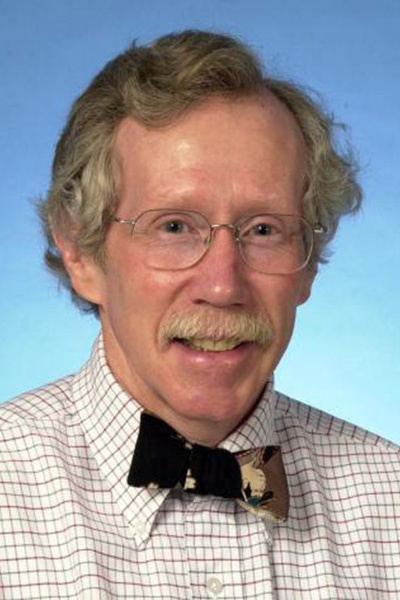

Jill Reedy

They’re really not saying this directly, but in a way they’re saying, “You guys are way too certain about what you told the public.” By the way, that’s the kind of thing that makes the public deeply skeptical about whatever scientists say, when scientists come on to seem to know more than they really know.

In this current situation, even if the recommendation had been something like a Task Force “I,” if they said, “We can’t tell you, you should make your decision based on other factors,” I think even then, they would’ve gotten blow-back.

It might not have been quite as bad, but I still think that people who had previously made strong recommendations on cutting back on meat would still have been incensed. I don’t know that there’s any way around that, just because they’re deeply committed to what they have already said in the past. But, according to the evidence, it’s just not there.

What would you tell your patients? What is your message to the public?

Reedy, NCI: It’s really challenging to identify all the different strategies that are needed to combat these kinds of sensational headlines and so-called guidelines like this that aren’t based on scientific evidence.

In a clinical setting, there are many different things to consider for a patient, and what their particular context and issues are. Similarly, for the public and for population health, guidance is grounded in the broader food environment, and how we can best support people to make healthy choices.

The recent study is of concern, because the public could interpret this as an actual new guideline. In reading these papers, it’s important to look across that totality of evidence and understand how current evidence-based guidelines are developed.

Nicastro, NHLBI: The Dietary Guidelines for Americans don’t limit any one protein source, but they do recommend a healthier eating pattern with more lean meats and limited red and processed meats. And that is still the recommendation that we should be putting out to the public.

Redberg, UCSF/JAMA: I will continue to recommend a Mediterranean-style diet. I like what Michael Pollan said, “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” And get regular exercise.

The other thing, and I think the authors said, “Well, it’s not our problem,” but besides the benefit directly from eating a diet with less meat—and it doesn’t have to be no meat, but certainly a lot less meat—there’s the effect on the environment.

There is a huge component of cows and methane production, and the inefficient protein that you get from eating meat that contributes to climate change. I think what I read, they also said climate change isn’t their problem, but climate change is all of our problems. I don’t agree with saying that that is not another reason that we should all be eating less meat. We have a very serious crisis of global warming, and meat consumption is contributing to it significantly.

We have to be careful to be as clear and consistent as we can, and I think, with diet, we certainly have a lot of good reasons to be very clear and very consistent that limiting the consumption of red and processed meat is really good for your health.

Daniel, MD Anderson: Continue to follow the dietary recommendations in their entirety. Take a look at them in their entirety, which is to eat more plant based foods, fiber rich plant foods, fruits, vegetables, legumes. If you’re going to consume grains, consume whole grains. If you’re going to consume meat, consume fish, consume lean proteins and consume vegetable-based proteins, and limit added sugars.

Overall, eat a variety of foods, but not too much. That has not changed just because a paper has come out on this. And, like I said, the evidence is actually strongest for processed meat that is red. There are different levels; a hamburger may not be the same as a piece of bacon in terms of how it impacts cancer mechanisms.

But we don’t get into that level of detail with public health recommendations. To make an analogy, we know that when we’re treating cancer, we usually start with the standard-of-care therapy. They don’t work for everyone; does that mean that we just throw them out the door and do something else?

No, we have to have a process to get to that and this paper has not changed that process. It becomes a part of that process, but that process is not being thrown out the window.

McCullough, ACS: This is a comprehensive systematic review of the evidence on meat consumption, whether reducing meat intake will influence cancer outcomes and other causes of mortality, and the authors actually find very similar associations that have been reported by others. So, in that sense, it’s confirmatory. The difference is in the interpretation of the data for individuals versus population benefits.

The American Cancer Society continues to recommend that people limit their consumption of unprocessed red meat, and especially processed meat, based on the totality of the existing evidence and conclusions by the World Health Organization that processed meats are carcinogenic and unprocessed red meat is considered a probable carcinogen.

The preponderance of the evidence is also reviewed using systematic literature reviews by the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. The current set of papers, again, really reinforce the risks that we’ve seen. The study uses different criteria for weighting the evidence, and they come to different conclusions based on their weighting of the evidence, and based on their consideration of people’s preferences for meat.

We used the authors’ estimates to calculate that by lowering processed meat intake by three servings per week, the number of lives saved from cancer death would be 8,000 per one million people.

Harris, UNC: I would say that a group of investigators—by the way, it’s not the journal that made the recommendations—has done a superb job of bringing together the literature on meat consumption and health. And what they have found is that the evidence of association between meat consumption and health has low or very low certainty. Even if we take whatever evidence we have as being sufficient, the magnitude of any effect in absolute terms is small or even very small.

Because of the literature being as difficult as it is, we cannot answer the question as to whether reducing meat consumption would improve health. People should make their decision on meat consumption on other grounds.

We used the authors’ estimates to calculate that by lowering processed meat intake by three servings per week, the number of lives saved from cancer death would be 8,000 per one million people.

Marji McCullough

There are really clear ethical and environmental reasons for cutting back on red meat. As environmental studies have shown recently we should be planting more trees and eating less red meat if we want to protect the planet.

Let me just say that we talked about this one threshold—when you’re doing reviews of evidence, that one threshold is, “How sure do you have to be? How certain do you have to be before you can make a recommendation?”

I’m suggesting that the threshold is higher than these folks did. So, these folks said, “This threshold is high enough for us to go ahead and say, ‘Keep doing what you’re doing.’ I’m suggesting that the best threshold would be higher than that, and we should say, in all honesty, to the public that this evidence is insufficient, so we can’t make a recommendation.

Let’s say we had enormous randomized trials, and they were really well conducted over many, many years. It’s impossible, but let’s say that we had those. The second threshold would be, “How big does the magnitude of benefit need to be before we make a positive recommendation?” And that comes up a lot also in evidence reviews.

The question about how big the effect is, is kind of a separate issue. Everything here has to do with the magnitude, with the certainty issue, the threshold, and how good is the evidence. The evidence here is really lousy.

We’ve written seven or eight different articles about evidence like this at the USPSTF, and we try to keep those two thresholds separate so that people can understand better. But here, the big issue is the threshold of certainty, and I don’t think the evidence has met it. And the authors seem to think that it did meet it.