Two years ago, as next-generation sequencing and checkpoint inhibitors became the standard of care in many cancers, Joan Massagué started hearing questions from philanthropists about the “next big thing” in cancer research.

There wasn’t an immediately obvious answer—the heyday for molecular characterization of cancers was already underway—but Massagué, director of Sloan Kettering Institute, realized that more investment was needed further upstream of the clinic, beyond oncogenes.

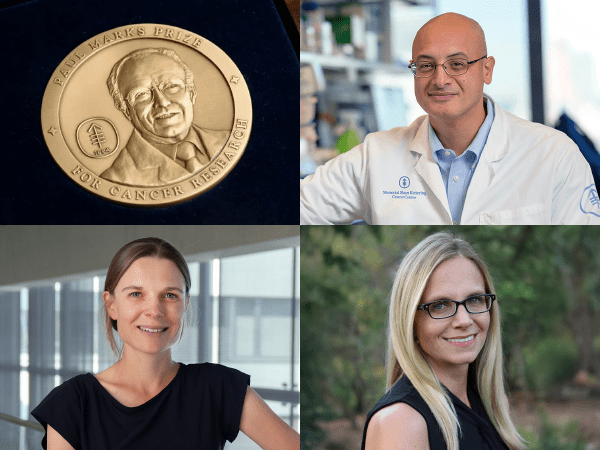

“Now is high time to go get concrete answers beyond what genes rendered cells more aggressive than their companions,” said Massagué, who has led SKI, the basic and translational research arm of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, since 2014.

“It’s a great watershed moment for physicians and scientists to come together and go get it,” he said to The Cancer Letter.

That goal of driving novel cancer science through preclinical research became a guiding principle for The Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Cancer Ecosystems Project, SKI’s flagship initiative within MSK’s latest strategic plan for preclinical research.

The project, which is funded by a $100 million gift from the Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Foundation, seeks to solve the mysteries of tumor metastases and the biological relationships between cancers and their environments.

CAR T-cell therapy and the advent of checkpoint immunotherapy, for example, stemmed from tumor immunobiology and the investigation of several immune cells and a few molecules, said Massagué, who serves as the chief strategist for the Kravis Cancer Ecosystems Project.

“There is much more where this came from to go get,” Massagué said. “That is how we came about, that we need the means and inspiration to mobilize people to go out of their routine high-end project, to come together and attack these questions.”

A guest editorial by Massagué and Marie-Josée Kravis, vice chair of the board of trustees at MSK, appears here.

The Kravis Foundation was established in 1985 by Henry R. Kravis, a business financier and investor who is a co-founder of Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co., an asset manager specializing in private equity, fixed income and capital markets. The foundation primarily provides support for education, arts and culture, and social services.

Why was SKI chosen for a cancer ecosystems program?

“We are not unique in being a cancer center that has great cancer research, translational and basic research on cancer,” Massagué said. “There are others. They are great, and they are all needed.

“But we are more unique in being a center that, in addition to that, has a very robust and very confident investment in basic science that is relevant to cancer, even though it is not yet at cancer.”

Mission: Double the pace of preclinical research

With a budget of $10 million per year over 10 years, the SKI project will be focused on de novo, meritoriousresearch that would be directed from within MSK, with invitations for experts with actionable concepts to collaborate and submit ideas—regardless of institutional affiliation or country of origin.

“We know each other. We know everybody. We know who is good at what,” Massagué said. “It’s going to be very concrete, very ready. For example, taking three groups now by coming together, they just get done in three years what would take otherwise six, with twice as many people and funds.

“But that is going to be not by a request for applications,” Massagué said. “It will be connoisseurs identifying people out there who they know have the goods or the talents needed to make the strongest possible case.”

A primary goal of the Kravis project is to empower current expertise and technologies to focus on a select set of grand challenges related to cancer progression, and to accomplish within 10 years what would otherwise require 20. Researchers would also look at how progressing cancers respond to—or fail to respond—to therapy, and how failure, i.e., metastases, could be prevented.

While the project isn’t designed for conduct of clinical trials, its scope isn’t limited solely to preclinical research, either.

“Biology, immunology, metabolism, a microbiome relationship of stress or age or whatever. It’s a long list. We are going to source from within this list,” Massagué said. “We’ll be very happy to solve, say, three big hits per year. Over 10 years, that’s 30 big hits that were accelerated.”

Other recent philanthropic initiatives in oncology with parallel “grand challenge” missions include:

- Break Through Cancer, a research alliance of five top-tier academic cancer centers that was announced with a challenge pledge of $250 million from William H. Goodwin, Jr., Alice T. Goodwin, and their family, and the estate of William Hunter Goodwin III (The Cancer Letter, Feb. 25, 2021).

- Cancer Research UK’s Grand Challenge, which supports multidisciplinary teams across the globe, has invested £200 million since its launch in 2015. In 2020, NCI and CRUK partnered to create the Cancer Grand Challenges (The Cancer Letter, July 21, 2017; June 17, 2022).

- Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, established in 2016 with $250 million from Sean Parker, brings together immunologists from premier academic institutions with industry and government (The Cancer Letter, April 15, 2016).

“We are excited for our colleagues at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center to be receiving this transformative gift from the Kravis family,” said Tyler Jacks, president of Break Through Cancer, and the David H. Koch Professor of Biology and director of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT.

“The approach of deeply investigating the genetic, epigenetic and environmental regulators of disease initiation and progression is important and timely,” Jacks said to The Cancer Letter. “We at Break Through Cancer look forward to interfacing with the investigators funded through the Kravis Cancer Ecosystems Project in collaborative efforts in the years ahead.”

MSK is a founding member of Break Through Cancer, and is a participant in the Cancer Grand Challenges as well as at Parker Institute. “It is interesting that different parties arrive at the same sense, that is, asking for task forces to self-identify themselves with a clear mission to conquer that hill,” Massagué said.

The SKI project will use a “systems-level approach” to study the tumor environment—separate from the discipline of systems biology—because cancer is a systemic disease that isn’t just about cells with certain constellations of mutations that determine progression and metastasis.

“Our bodies have defenses of all kinds to prevent this from happening almost every minute of the day or every day. This happens in the context of a whole body system,” Massagué said. “So, our term ‘systems’ has to do with the fact that the questions that we’re going to concentrate on are, for example, why do immune cells that are rallying to invasive tumors become exhausted and become subjugated by that tumor?

“What biology in the immune cells is the tumor exploiting to muffle them and how could that be reversed?”

Following that, there is an abundance of hypothesis-generating questions for the SKI project to interrogate. For instance:

How are metabolic conditions of the whole organ impacting a cancer’s ability to evade the immune system and dampen natural regulatory processes?

How is the microbiome directly impacting a tumor resistance mechanism that has been linked to the microbiome? What is the biology?

Based on existing literature on the biology of disseminated disease, what is known or unknown about residual disease after a tumor or a metastasis responds well to therapy?

What aspects of the biology of dormant disseminated cells, prior to a first relapse, is recaptured by a disseminated population after significant, but not fully successful, elimination of a tumor mass by combinations of targeted therapy and immunotherapy?

What are the vulnerabilities of residual disease, knowing the biology of resistance in residual cancer cells?

“These are all cases in which the whole-body system can impact the answer,” Massagué said. “There could be systemic immunity. There could be clonality phenomena, explaining how the answer may differ depending on the age of the individual.

“The imagination is the limit about what it could be.”

Massagué: Let’s invite great partners and solve mighty problems

The SKI-Kravis model for accelerating research and sourcing expert partners is innovative, as well as reminiscent of the Biden administration’s push to create “transformative” progress in cancer research through the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health, or ARPA-H, using unconventional collaborations across a broad spectrum of stakeholders (The Cancer Letter, April 9, June 18, 2021).

Like ARPA-H—which sparked discussion about what the agency can do to complement NCI’s basic and translational science portfolio—the SKI project can be expected to inhabit the gray area between solving engineering problems in oncology and addressing scientific questions that aren’t ready to be solved through engineering (The Cancer Letter, April 23, 2021; May 6, 2022).

“It will not be wide open, curiosity-driven research. We have that, too; we have support for that as well—very generous support,” Massagué said. “But this is going to be very problem-directed. Problems that within three years of activity ought to be solved.

“What shape this will take, time will tell. It’s biology. Biology is very soft around the edges,” Massagué said. “The intention here is just to contribute as an institution through our resources and through these additional wonderful resources to help the field make the biggest possible difference. That’s what we’re all about.”

Massagué anticipates that SKI will be working with other institutions, including the NCI, to eliminate potential redundancies and ensure that the project is funding research that fills a knowledge gap.

“If we become aware that the NCI or other bodies have great activity in that area, we will want to coordinate that, to do it as economically and frugally as possible, in as coordinated a manner as possible,” Massagué said.

MSK and the Kravis Foundation have done this before.

The cancer center’s Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Center for Molecular Oncology—which is now “self-propelled” to expedite and streamline cancer genomics research and guide cancer treatment—was established in 2014 with a similar $100-million-over-10-years gift from the Kravis Foundation.

Another noteworthy investment at MSK is the $50 million Alan and Sandra Gerry Metastasis and Tumor Ecosystems Center, designed to support research initiatives that specifically focus on metastasis.

“All of these have given us a sense of what is possible with philanthropic support,” Massagué said. “We are emerging enriched by the knowledge and insights that cancer genome science has put on the table and all the additional ancillary technologies, single cell analytics, and so forth.

“It is now high time that we address the questions that affect the patient in the clinic—the fear of relapse, the fear of metastasis, the fear that there are behaviors in diet, in exercise, that may affect positively or negatively the course of their disease, or what they perceive to be the possibility of disease, latent disease, dormant disease.

“While we will not be able to provide all these answers quickly, these are the kind of answers that is now the time to go after.”

Peer review for research funded by the SKI initiative will be conducted on an ad hoc basis and tailored to the projects under review. Panels will include teams composed of external reviewers and one or two internal reviewers.

“The leadership of the whole endeavor will be aware of those projects [and] who is coming together,” Massagué said. “But we will not let that impression dominate or bias the awarding.

“We are going to call in experts to say whether this has a good chance of cracking open a problem,” Massagué said. “Those external colleagues would be procured from the worldwide community.”

An argument for robust investment in basic cancer science

SKI has a mission to fund “any and all” science that is relevant to cancer, including projects that, at a singular point in time, may have no direct link to cancer.

“We believe that this will end up impacting cancer in a way that very directly benefits the patient,” Massagué said. “We believe that not just as an act of faith, but, by now, one after another, examples from history where that happened.”

Massagué said his initiative stands on the shoulders of giants at SKI:

- In 1984, physician-scientists Malcolm Moore and Karl Welte isolate granulocyte colony-stimulating factor from human cells that stimulates new blood cell growth and could be used to boost the ailing bone marrow stem cells of patients undergoing cytotoxic therapies. G-CSF forms the basis of filgrastim (Neupogen), one of the most impactful cancer drugs to be developed.

- Physician-scientist John Mendelsohn, who co-led the SKI Molecular Pharmacology Program from 1985 to 1990, developed the concept of using antibodies to block the epidermal growth factor receptor as a way to treat cancer—spurring the development of the EGFR-blocking drug cetuximab (Erbitux) and opening a path for other growth factor receptor-targeting drugs, including trastuzumab (Herceptin).

- In 2002, Michel Sadelain, Renier Brentjens, and Isabelle Rivière developed genetically engineered T cells with a chimeric antigen receptor, which at the time involved assessing the ability of these T cells to recognize cancer cells in a Petri dish. FDA approved the first CAR T therapies, Kymriah and Yescarta, in 2017 (The Cancer Letter, July 14, Oct. 20, 2017).

Not too long ago, basic research was siloed within basic science-directed programs, including structural biology, cell biology, and molecular biology.

“Not anymore,” Massagué said. “We have basic research projects in most labs at SKI, and we have cancer-directed, including translationally-intended projects in most labs, or in many labs at SKI, regardless of whether these labs are in a program that, overall, is more basic-oriented or more translation-oriented.

“There is full amalgamation, as it should be, because this is what cancer demands of us as scientists. We cannot be self-contained in discipline-oriented means,” Massagué said. “But we are called upon to solve problems or acquire the knowledge, basic knowledge, to solve these problems, whatever it takes.”

History has proven that special emphasis on basic science is a “great secret component of the sauce” for patient benefit and progress in cancer medicine, Massagué said.

“That also distinguishes us from other institutions, which are restricting themselves more to cancer research that has a clear, certain path to translation,” Massagué said.

“That’s the vision, and the reality, and how we cultivate SKI going forward.”