Source: NCI

In 1984, Peter Greenwald brought a concern about food labeling to FDA. He felt that the “standards of identity”—the standards a food product must meet in order to be marketed under a certain name—went against the best available public health evidence.

“Some of the foods, for example margarine, that might have been healthier than butter, but the FDA was forcing the labels to say ‘artificial’ or some word that had a negative connotation,” Greenwald said in an oral history interview conducted by FDA in 2009. “It seemed that the butter and other industries wanted that, and I didn’t think it was evidence based.”

Greenwald asked then-director of the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Sanford A. Miller, to change the standards of identity to “give them a public health message.” FDA was not receptive.

“The FDA staff were very gracious and very nice. But Miller said, ‘You know, we’ve been working this way since… 1938, for a long time, ‘and we’re not going to change, but we wish you the best doing your work.’ You know NCI. ‘We’re happy that you’re going to work on nutrition education, but we can’t really partner in a formal way.’”

So, when Greenwald was approached by the Kellogg Company with a request to develop language stating that dietary fiber can help prevent colon cancer, he said “Yes.”

“Our response was a conditional yes. Yes, only if you put the entire message—eat more vegetables and fruits, cut down on fat, and eat more fiber—and they agreed to that. And literally, that’s what they did. If you go and find the pictures of the old cereal boxes, you’ll see that they have the entire message.”

The data supporting the claim was part of a holistic spread of evidence that was publicized as part of NCI’s 1984 Cancer Prevention Awareness Program.

“We put together a balanced message, and in general, we followed the USDA-HHS guidelines. Our message was: eat a balanced diet with more vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, cut down on fat,” Greenwald said. “They blanketed TV networks with simultaneous ads on all major networks. Every TV station had the same message at the same time. They did a lot of marketing.”

For Greenwald and NCI, this was great news. Their message was being widely disseminated to the public.

The NCI Budget Fact Book for Fiscal Year 1985 contains a synopsis of the Cancer Prevention Awareness Program and its aims:

Today we know that nearly 80 percent of cancers are related to environmental causes, many associated with personal behavior such as cigarette smoking and eating habits. However, a survey conducted by the NCI in June 1983 revealed that the public’s view of cancer is confused; people are pessimistic about cancer risks and the potential for personal control over those risks.

In March 1984, NCI introduced the Cancer Prevention Awareness Program-a major NCI effort to increase public awareness of the possibilities for cancer prevention, presenting a challenge to the American people to learn what they can do every day to control their own risks.

The program theme, “Cancer Prevention: The News is Getting Better all the Time”, encourages optimism. Messages emphasize personal control, explaining that every day individuals can take steps to control their own cancer risks.

For example, don’t smoke or use tobacco in any form; eat foods high in fiber and low in fat; and include fresh fruits, vegetables, and whole grain cereals in your daily diet.

The program is being implemented in two phases. Phase I relies primarily on mass-media efforts to create awareness of prevention messages and to encourage people to learn about cancer prevention from a free NCI booklet available by calling 1-800-4-CANCER.

With Phase II of the program, which began in 1985, the emphasis shifted from the general public toward populations at greater than average risks, and in May, NCI launched a program for Black Americans. Efforts are also underway to reach Hispanics, Asian Americans, children and youth, and women.

The program also initiated a diet and nutrition education program in 1985. A free booklet “Diet, Nutrition and Cancer Prevention: A Guide to Food Choices”, which provides many suggestions for more healthful eating habits, was published and distributed.

Greenwald did not anticipate the torrent of consequences that followed NCI’s collaboration with the Kellogg Company.

“The problem was, as you can probably figure out from that, my guess—and I cannot verify this—is that they held some focus groups, and they knew the message people would receive was fiber is All-Bran; eat more All-Bran and you’ll get less cancer,” Greenwald said.

The All-Bran labels came under scrutiny by FDA, which had a policy prohibiting health claims on food labels.

Source: FDA Consumer, November 1987, page 23

“Many of the nutrition scientists at the FDA and elsewhere were quite upset with us, saying, ‘Look, you set this off. It’s shaken up our whole policy of not allowing health claims on foods, which we think is a solid, reasonable policy that keeps us out of trouble,’ and changed the picture.”

The Kellogg incident marked the first time a manufacturer claimed that a food could help prevent a specific disease. FDA, in the end, did not order Kellogg to change its All-Bran messaging.

“I think I was a little naïve in this… this was used as a wedge, I would say, by the Reagan administration, not by us, and by industry to put implied health claims on foods or this sort of thing on foods,” Greenwald said. “That’s still going on. For example, misleading statements implying orange juice prevents cancer. That went on.”

Said Greenwald:

Whether intended or not, it did lead to a huge change. A lot of the change was not the intent, but it had a big impact.

I think there was a good impact on eating of fiber. It stimulated research on fiber. The NCI coding systems were insufficient at that time. The codes didn’t say fiber; there was little study of fiber.

And also the fat issues. There were scientific groups that said maybe we’d better study that, some for good academic reasons, some saying we think you’re full of it.

But there were studies, and from our point of view, they helped to focus peer-reviewed grants. A lot of research was stimulated. It focused more research on nutritional science—not as much as we needed, but it helped in that sense.

On the downside, probably it would have been better if we’d gotten together with the FDA on this specific issue beforehand.

But Sanford Miller had said we should do it our way. The FDA didn’t want to work with us on this. The FDA was friendly, but I think they probably just would have tried to squelch any dietary guidance related to food products.

This oral history, along with 301 others conducted by FDA, have been hidden following the Trump administration’s order to purge government websites containing anything related to DEI or gender. The PDFs with transcriptions of the interviews are still online, but the central FDA landing page which formerly directed users to the agency’s collection of oral histories has been removed.

A partial list of scientists and officials who participated in FDA’s oral history project can be found in this issue.

Greenwald also participated in the NCI Division of Cancer Prevention Oral History Project, completing a set of three interviews in 2008, and a fourth in 2023.

The interview synopses reads:

In interview one, Dr. Greenwald traced education and employment activities that prepared him for his work at NCI. He noted a summer fellowship in Iran during medical school that permitted him to learn about many conditions rarely seen in the United States, particularly cutaneous anthrax.

He emphasized his training and experiences as an Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) officer at what is now called the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which advocated assessing a public health problem and addressing it with action.

This contrasted with his postgraduate public health training at Harvard University, which emphasized rigorous, evidence-based methods for statistical research on chronic diseases, especially cancer.

He described his decision to unite the two training philosophies by accepting in 1968 a position as Director of the Cancer Control Bureau, New York State Department of Health and gave examples of his work before coming to NCI in 1981.

Interview two described how he created a new Division of Cancer Prevention and Control (DCPC) at NCI and on the programs DCPC sponsored.

Dr. Greenwald outlined the philosophical concepts of cancer “prevention,” cancer “control,” and cancer “etiology” and how he implemented evidence-based research on cancer prevention and control.

Specific programs that he discussed during this interview include the Smoking and Tobacco Control, Diet and Cancer, Chemoprevention, and the Community Clinical Oncology Program, with subgroups emphasizing the needs of minority populations to address health disparities.

Two particular clinical trials discussed in detail were the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project and the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial.

Interview three continued the discussion of major clinical trials supported by Dr. Greenwald’s division and also detailed internal NCI administrative processes by which resources were allocated to different divisions.

The difficulties of nutritional research for cancer prevention and of defining valid biomarkers for indicating stages in the process of carcinogenesis were also detailed.

Dr. Greenwald commented on the priorities of different NCI directors and the effect they had on his efforts to identify risk reduction for specific cancers through clinical trials.

Greenwald retired from NCI in March 2011. His full oral history, recorded Aug. 26, 2009, is available in the Cancer History Project, along with oral histories recorded by NCI in 2008 and 2023.

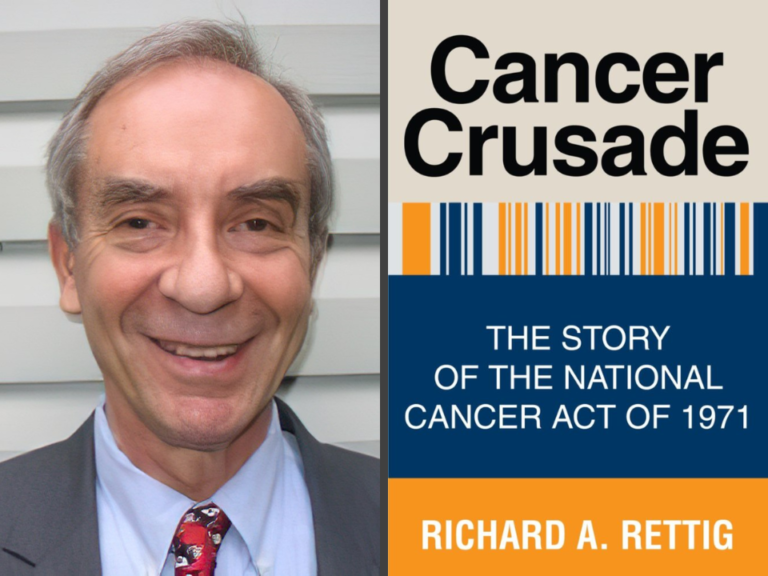

This column features the latest posts to the Cancer History Project by our growing list of contributors.

The Cancer History Project is a free, web-based, collaborative resource intended to mark the 50th anniversary of the National Cancer Act and designed to continue in perpetuity. The objective is to assemble a robust collection of historical documents and make them freely available.

Access to the Cancer History Project is open to the public at CancerHistoryProject.com. You can also follow us on Twitter at @CancerHistProj, or follow our podcast.

Is your institution a contributor to the Cancer History Project? Eligible institutions include cancer centers, advocacy groups, professional societies, pharmaceutical companies, and key organizations in oncology.

To apply to become a contributor, please contact admin@cancerhistoryproject.com.