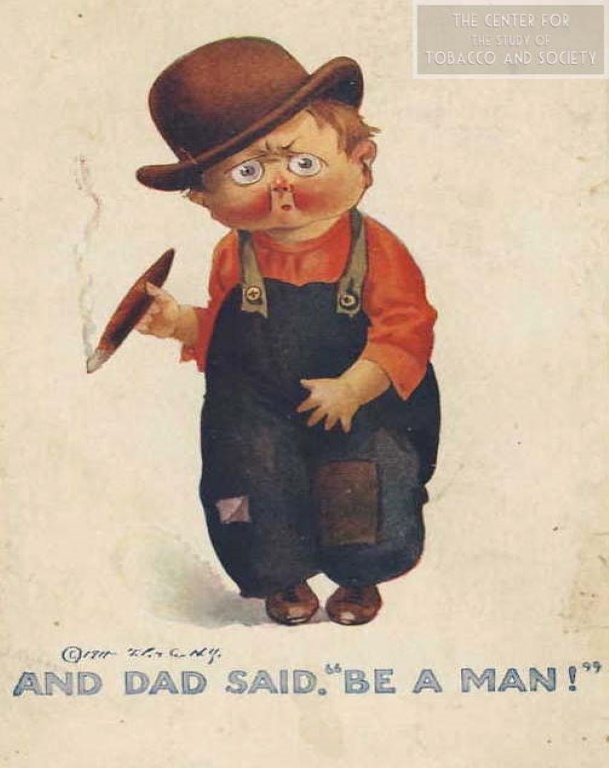

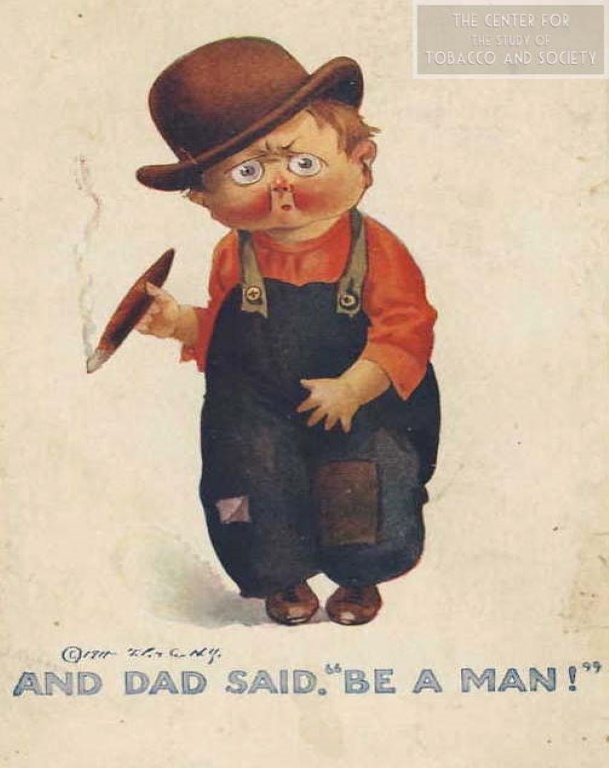

Alan Blum, director of The Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society, documents advertisements from tobacco companies during “an era not very long ago when a son giving his dad a gift of a carton of cigarettes was as American as apple pie.”

Blum’s center has put together an online exhibit featuring tobacco advertisements from those days.

- Life father, like son: How tobacco companies targeted families in the 20th century

By The Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society | June 8, 2023

Excerpted from the The Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society’s online exhibition, “Like father, like son: Smoking as family tradition.”

Writes Blum:

I could well have been that freckle-faced little boy on the sign handing a carton of Chesterfield cigarettes to his dad. My father, who had been a high school track and field athlete, started smoking Chesterfield cigarettes as a medical student.

By the time he served in the Army in World War II, he was smoking up to two packs a day. This was a decade before epidemiologists and pathologists confirmed in the 1950s that smoking caused heart disease (see the center’s exhibition “‘Tobacco Heart!’ Smoking and Cardiovascular Health.”) As a result of his ever-present cigarette, he suffered a heart attack in 1953 at age 44 (when I was just 5) and died at age 60.

On the whole, the pharmaceutical industry not only looked the other way when it came to smoking, but at least one company, Merck Sharp and Dohme, encouraged it by sending personally embossed matchbooks to physicians with ads for its new antihypertensive medications, DIURIL (chlorothizaide) and HYDRODIURIL (hydrochlorothiazide). Other companies depicted smoking patients in their ads, recommending medications for the conditions caused by smoking, rather than trying to aid physicians in prevent these diseases by educating the public not to smoke (see the center’s exhibition “Depictions of Smoking in Pharmaceutical Advertising“).

One of my father’s passions was rooting for the Brooklyn Dodgers, and in 1956 as we were watching a game on WOR-TV, he suggested that I use our new Webcor audio tape recorder to save examples of the endless commercials for Lucky Strike cigarettes, one of the team’s sponsors. “One day, no one will believe that sports was used to promote smoking,” he predicted. This was the origin of the Center of the Study of Tobacco and Society.

You can view the Lucky Strike billboard in right field at the Dodgers’ stadium, Ebbets Field, in a video clip from the pregame TV show, “Happy Felton’s Knothole Gang,” in which Jackie Robinson tosses grounders to a little leaguer. And you can listen to the play-by-play of the final inning of a Dodger game in 1956 in which pitcher Sal Maglie is throwing a no-hitter and Dodger announcer Vin Scully is pitching Lucky Strikes.

Throughout the 20th century and to the present day, millions of fathers have died from heart disease, emphysema, and lung cancer due to smoking, even as the tobacco industry denied that their products could even cause a cough. Meanwhile, cigarettes were advertised on billboards in sports stadiums, on displays in stores, on TV and radio until banned from the airwaves in 1971, and then increasingly in newspapers and magazines and at entertainment venues.

View the full online exhibit on the Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society website.

Listen to the latest podcast commemorating the 50th anniversary of Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center

- Podcast: 50th Anniversary of the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center Podcast Series – Drug Development

By Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center | June 7, 2023

The next podcast looking back at the history of the cancer center at Johns Hopkins features Dr. Bill Nelson and Dr. Ross Donehower discussing the origins of the drug development program and its first director, Dr. O. Michael Colvin.

This column features the latest posts to the Cancer History Project by our growing list of contributors.

The Cancer History Project is a free, web-based, collaborative resource intended to mark the 50th anniversary of the National Cancer Act and designed to continue in perpetuity. The objective is to assemble a robust collection of historical documents and make them freely available.

Access to the Cancer History Project is open to the public at CancerHistoryProject.com. You can also follow us on Twitter at @CancerHistProj, or follow our podcast.

Is your institution a contributor to the Cancer History Project? Eligible institutions include cancer centers, advocacy groups, professional societies, pharmaceutical companies, and key organizations in oncology.

To apply to become a contributor, please contact admin@cancerhistoryproject.com.