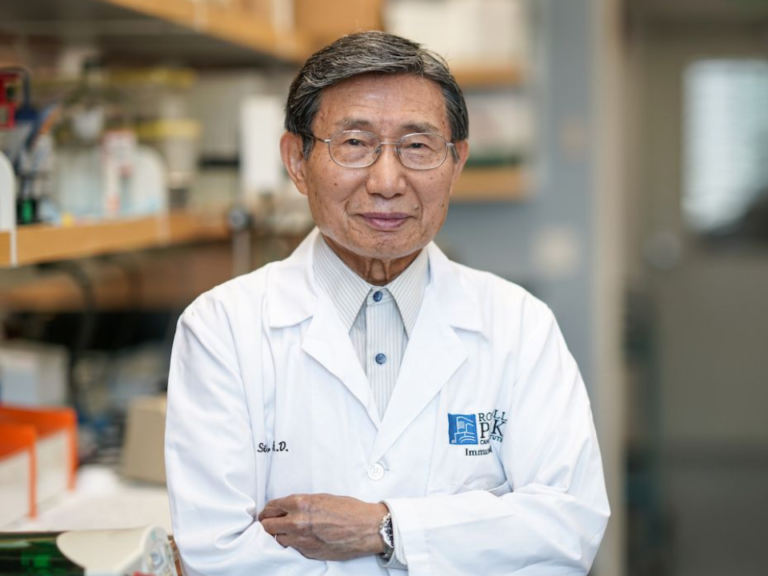

John A. Zaia, director of the Center for Gene Therapy at City of Hope, died on Feb. 11 following a battle with pancreatic cancer. He was 82.

Dr. Zaia, also the Aaron D. Miller and Edith Miller Chair for Gene Therapy and founding director emeritus of the City of Hope Alpha Stem Cell Clinic, earned renown as a premier virologist and gene therapy pioneer. He is recognized worldwide for his breakthrough efforts to eradicate HIV as well as for his work in pediatric diseases.

“Dr. Zaia was a gentleman and a scholar, a voice of reason during times of chaos, and a source of wisdom for so many of us trying to navigate this world. He loved our department of pediatrics and was so proud to be a part of our family,” said Saro Armenian, professor in City of Hope Children’s Cancer Center and the Barron Hilton Chair in Pediatrics. “I will miss our visits together and will hold on to the memory of the twinkle in his eyes each time we talked about a new project or initiative for our patients.”

Asked in a 2020 interview why he chose to study viruses early in his career, Dr. Zaia morphed from medical man to wide-eyed wonder, explaining his affinity for microscopic parasites in much the way Monet might have considered the flowers in his Giverny garden.

“The first time I looked at one of those tissue cultures under a microscope,” he recalled, “I could see their beauty. It was remarkable.”

To the average person, “beauty” is probably not the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about the viruses that cause AIDS, Ebola, or the common cold.

But then, “average” is the last thing anyone would say about the physician-scientist who marked 44 years at City of Hope.

“He was a truly wonderful human being, an excellent physician and a great scientist,” said hematologist-oncologist Stephen J. Forman, a longtime colleague and friend. “He never lost his sense of scientific wonder and always displayed insight and wisdom. When people would on occasion be upset and lose their cool, he was always the calm one in the room.”

In those four-plus decades, Dr. Zaia leveraged his wisdom and wonder into a keen understanding not only of how viruses work, but also how best to control their destructive properties as well as how to harness their hardiness and mobility to deliver a new generation of precision medicine and gene therapy.

Tackling infectious diseases in children

A native of Onieda, New York, and son of a physician (“I always knew I was going to be a doctor. I didn’t see anything else”), Dr. Zaia took his dual Dartmouth and Harvard Medical School degree and initially focused on infectious diseases in children.

It started with chickenpox.

Working with outdated blood from the Massachusetts blood bank, Dr. Zaia helped advance the research that eventually made a widespread vaccine feasible. He also became known as the go-to person for treating kids with leukemia who contract chickenpox, a life-threatening situation when chemotherapy weakens the immune system.

Dr. Zaia also studied cytomegalovirus (CMV), a common bug that’s usually harmless but can be lethal in newborn infants, with their still-incomplete immune systems.

CMV remained a major area of research for Dr. Zaia and his lab because of its potentially deadly effects on other vulnerable populations, such as people undergoing stem cell transplants and those with HIV.

When it comes to battling HIV and AIDS, few can match Dr. Zaia’s achievements.

Arriving at City of Hope in 1980 just as the epidemic was exploding, Dr. Zaia recognized the potential “home run” before him: AIDS was the curse, the challenge and the opportunity of a lifetime.

“People with HIV can now live a normal lifespan, thanks to antiviral drugs,” he said in 2020. “But that’s not the same as a normal life. They still have to take meds every day.”

Dr. Zaia remained doggedly determined to fix that, with his goal being to create a “functional cure” in which HIV, though it remains in the body, is incapable of doing harm. He approached this outcome several different ways, including using gene editing to modify blood cells to resist HIV and then using those cells for transplants.

Another strategy employed a lentivirus—in effect, using a virus to stop a virus. Even CMV—his old nemesis—is capable of being weaponized to stimulate dormant HIV so it can be recognized and attacked by chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells.

Dr. Zaia was especially excited about CAR T’s potential to fight HIV. City of Hope scientists developed CAR T cells that can target and kill HIV-infected cells and control HIV in preclinical research. They are currently conducting further clinical trials using CAR T cell therapy, which has the potential to provide HIV patients with lifelong viral suppression without having to take medication.

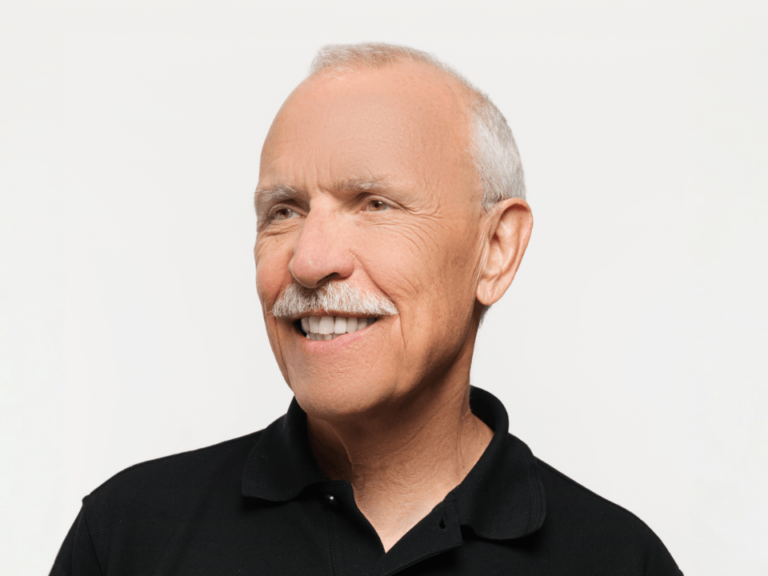

The “City of Hope patient” beats HIV

A penultimate moment of Dr. Zaia’s career was when a City of Hope patient, Paul Edmonds, became only the fifth person in the world, and the oldest and longest infected, to be cured of both HIV and leukemia following a stem cell transplant from a donor with an HIV-resistant genetic mutation in 2022.

Edmonds’s medical team needed to tailor his treatment to address his age and the decades-long duration of his HIV infection.

City of Hope’s expertise in treating older adults with cancer and HIV—efforts led by Dr. Zaia—proved to be invaluable in treating Edmonds and helping him go into remission for both diseases.

Asked in a 2020 interview why he chose to study viruses early in his career, Dr. Zaia morphed from medical man to wide-eyed wonder, explaining his affinity for microscopic parasites in much the way Monet might have considered the flowers in his Giverny garden.

“The City of Hope patient is another major advancement. It demonstrates that research and clinical care developed and led at City of Hope are changing the meaning of an HIV diagnosis for patients across the United States and the world,” Dr. Zaia said at the time.

Beyond AIDS, Dr. Zaia was heartened by the growing number of gene therapy drugs and predicted major progress in the coming years for gene therapies to treat lymphoma and sickle cell disease, among others.

Dr. Zaia was also a key member of the team that developed City of Hope’s unique COVID-19 vaccine in 2020, formulated to be effective for immunocompromised patients, such as those with cancer and HIV.

Studies of the vaccine, COH04S1, showed it to be safe and effective. The vaccine was licensed by GeoVax in 2021 and will soon enter a phase IIb clinical trial testing its effectiveness compared to a Food and Drug Administration-approved mRNA COVID-19 vaccine.

And as program director of City of Hope’s California Institute for Regenerative Medicine-funded Alpha Stem Cell Clinic, Dr. Zaia conducted stem cell-based research, including a study to administer blood plasma from recovered COVID-19 patients to treat those with the virus.

Dr. Zaia was honored in 2023 by Dartmouth School of Medicine with a Lifetime Achievement Award, recognizing his many contributions to medicine and science.

Passion for sports, the outdoors

Known to his friends and family as the ultimate Renaissance man, Dr. Zaia was a passionate fly fisherman and photographer who loved to hike in Eaton Canyon and the West Fork of the San Gabriel Mountains. He was an avid sports fan of all kinds and was an eager participant in the annual NCAA tournament bracket the Virus Pool.

Dr. Zaia loved spending time with his family, whether laughing and sharing stories around the dinner table, playing bocce ball in the backyard or cheering on his grandchildren at their sporting events.

Longtime collaborator and friend Don J. Diamond, professor in the Department of Hematology & Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation, who worked with Dr. Zaia on a cytomegalovirus vaccine (Triplex) and other projects, fondly recalls their discussions that spanned science and basketball while watching Laker games at Crypto.com Arena. “We had great times that were heightened by the suds we both drank to watch the game when the Lakers were good as well the opposite,” Dr. Diamond said.

Having worked at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and taught at Harvard Medical School, Dr. Zaia says he “fell in love” with City of Hope right from the start.

“City of Hope is the ideal place to do my work,” he said in 2020. “I enjoy every single day.”

“He felt more passion about his work than anyone else I have ever met,” said his daughter Brita “Brie” Zaia, who was inspired by her father to follow in his footsteps and become a physician.

Dr. Zaia is survived by his wife Connie, daughters Sarah Rome and husband Jason Rome, Kate Sinclair and husband Peter Sinclair, and Dr. Brita Zaia and partner Monica Rosa, and five grandchildren: Mary, John, Jack, Madeline and Kate.

According to a statement from Dr. Zaia’s family, he was “a lifelong learner with endless curiosity. He was a dedicated and brilliant clinician and scientist. His contributions to the worlds of science and medicine are nothing short of extraordinary and will undoubtedly have a lasting impact. As remarkable as he was in his field, he was equally devoted as a husband, father, ‘Grampy,’ friend and colleague. His legacy, along with his love for life and all those around him, will continue to inspire us all for our lifetimes.”

Samantha Bonar is a content development senior manager at City of Hope.

Abe Rosenberg is a freelance writer.