Can one be too smart? In some disciplines such as physics and mathematics the answer is clearly no. In medicine, the answer is not so clear.

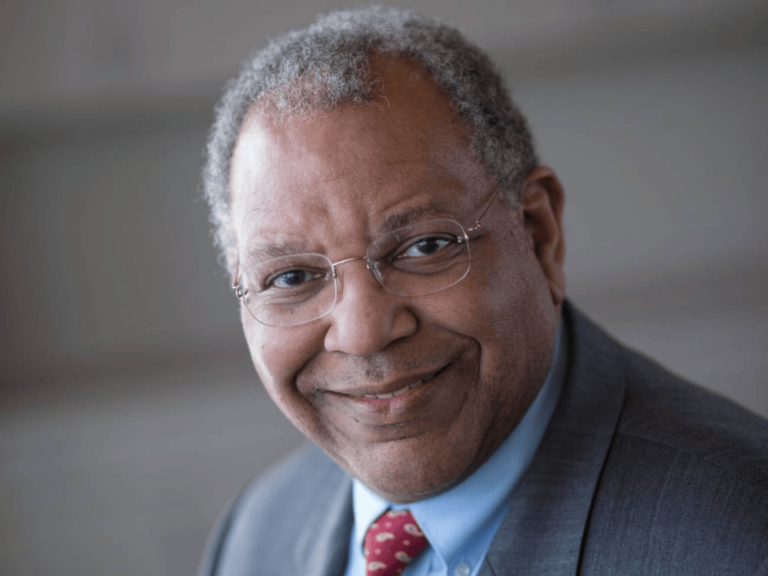

Emil J Freireich was a genius, a descriptor too often casually given (for example, to everyone’s child). Genius comes from the Latin word for guardian, deity, or spirit, which watches over each person from birth. The Oxford English Dictionary defines genius as an exceptional intellectual or creative power or other natural ability. By this standard there is no doubt J had genius and was a genius.

But, back to the question whether someone can be too smart. I have always regarded Prof. Freireich as a modern version of Baruch (de) Spinoza, the 17th century Dutch Enlightenment philosopher of Portuguese, Sephardic ancestry.

J, born in the United States in a humble Jewish background from Hungarian immigrants, rose to the highest echelons of medicine. (J, not Jay or J. was his actual name; just the letter) (The Cancer Letter, Feb. 5, 2021). Spinoza, who was deeply educated in Judaism, began to question the authenticity of the Bible.

Naturally, he was considered a heretic and blasphemer and exiled from the Jewish community of Amsterdam in 1655. The irony of Spinoza’s life was that despite this, he was also rejected by Christians.

Spinoza’s books, especially “Ethics,” were later added to the Catholic Church’s Index of Forbidden Books. Spinoza was frequently called an atheist Jew by contemporaries, although nowhere in his work did he argue against the existence of God. If this seems an oxymoron consider the Aesop fable of the Wolf and the Lamb.

You may be wondering what any of this has to do with Prof. Freireich.

First, like Spinoza, Freireich was never comfortable with his Jewishness, preferring to be branded a Texan with his ten gallon hat and cowboy boots. He once brought Texas wines to a leukemia meeting I organized in the Texas Hill country. The French were aghast.

J’s genius, along with Profs. Emil Frei and James Holland (my teacher) at NCI, was to develop the concept of multiple drug therapy of childhood leukemia. This concept was against thinking of the medical establishment and he was, in some sense, excommunicated.

Photo courtesy of G. Terry Sharrer, PhD, National Museum Of American History.

However, like Spinoza, he forged ahead and was proved correct. Had he been at a university rather than the NCI, it’s unlikely Freireich would ever have received tenure.

Back again to the question of whether one can be too smart.

J often thought he knew the truth before there were supporting data, or that he could deduce the truth from a large dataset without needing a randomized controlled clinical trial.

For example, although everyone saw the problem of low platelets in persons receiving bone marrow suppressing drugs, only, J saw the obvious and rather simple solution: give platelet transfusions.

No randomized controlled trials data needed, although we are still uncertain what blood platelet concentration requires transfusions.

Another contribution was his observation that in persons with acute myeloid leukemia, only those achieving < 5% bone marrow myeloblasts lived long, and that the duration of their survival correlated with the duration of this interval.

We used this as the definition of complete remission for nearly 50 years.

Also, he and Prof. Gerald Bodey identified that infection risk increases markedly when blood granulocytes are < 0.5 x 10E+9/L. Again, we use this landmark today for starting antibiotics.

However, Prof. Freireich said randomized controlled trials were often not needed to answer important clinical questions.

This heterodoxy, rejecting randomized controlled trials because you knew the answer was, and is, to most academicians, equivalent to Spinoza’s questioning the Bible’s authenticity.

Not that his thinking was wrong. It’s simply that non-geniuses like most of us need a scientifically valid way to determine the truth when absent of the input of geniuses like J.

For example, he was a strong proponent of granulocyte transfusions for persons with AML and infection, and questioned why Clara Bloomfield, several colleagues, and I would subject one-half of subjects to a placebo in a randomized controlled trial (The Cancer Letter, March 6, 2020).

The trials showed granulocyte transfusions were not only ineffective, but also increased deaths, especially in subjects receiving concurrent amphotericin. Years later, he told me I lacked any intellectual creativity and made my reputation and career disproving his brilliant ideas. Probably correct.

Spinoza lived an outwardly simple life as a lens grinder collaborating on microscope and telescope lens designs with the Huygens and turning down rewards and honours throughout his life. This was clearly not J.

Once he and I dined at Le Cirque, which along with the Four Seasons, was one of the most elegant New York restaurants, courtesy of Farmitalia, makers of daunorubicin. J was dressed in his usual cowboy hat and boots. At over six feet tall, he was an imposing figure in a restaurant filled with tuxedoed diners.

When the waitress approached to take our order he said: “Got any of those little black eggs?”

She looked puzzled for a moment and then replied: “Sir, do you mean caviar?”

“That’s it, he said, bring us a bunch!”

I was mortified, but it did not stop me from joining him. Now you know why daunorubicin was so expensive.

I believe Dr. Pasquale Cetera, our host that evening, was held hostage until his American Express charge was authorized.

Spinoza died at the age of 44, in 1677, from a lung disease, probably silicosis from inhaling glass dust whilst grinding lenses. He is buried in the Christian churchyard of Nieuwe Kerk in Den Hague, The Netherlands. (Protestant naturally).

Fortunately, Prof. J Freireich lived to 93, remained professionally active, and continued contributing many ideas to the advancement of medicine, especially oncology. His death is a great loss to his colleagues and friends and the thousands of young lives he saved with his heterodox ideas.

He was a giant in many ways, not unlike Spinoza.

Hegel said of Spinoza: “The fact is that Spinoza made a testing-point in modern philosophy, so that it may really be said: You are either a Spinozist or not a philosopher at all.”

Might we say: You are either a Freireich or not an oncologist at all?

Because of his accomplishments and moral character Spinoza is sometimes called the prince of philosophers.

Such is the reputation of Prof. Emil J Freireich.

In closing, it’s worth noting that “Baruch” means a blessing in Hebrew whilst “Emil” means to strive or excel in German.

We have both with Prof. Emil J Freireich.