This story is part of The Cancer Letter’s ongoing coverage of COVID-19’s impact on oncology. A full list of our coverage, as well as the latest meeting cancellations, is available here.

As U.S. health systems switch to telehealth to connect with patients—via phone calls and online video conferencing—during the COVID-19 pandemic, providers are quickly learning that the lack of a national infrastructure for telehealth is making it difficult to reach patients.

Because of arcane licensure rules, many physicians are unable to practice medicine across state lines. Also, reimbursement for telemedicine is neither standardized nor assured, leaving hospitals to grapple with myriad public programs and individual private payers.

With rapidly vanishing basic supplies, hospitals in COVID-19 hotspots do not have the luxury of time to think about expanding access while their beds fill with dying patients.

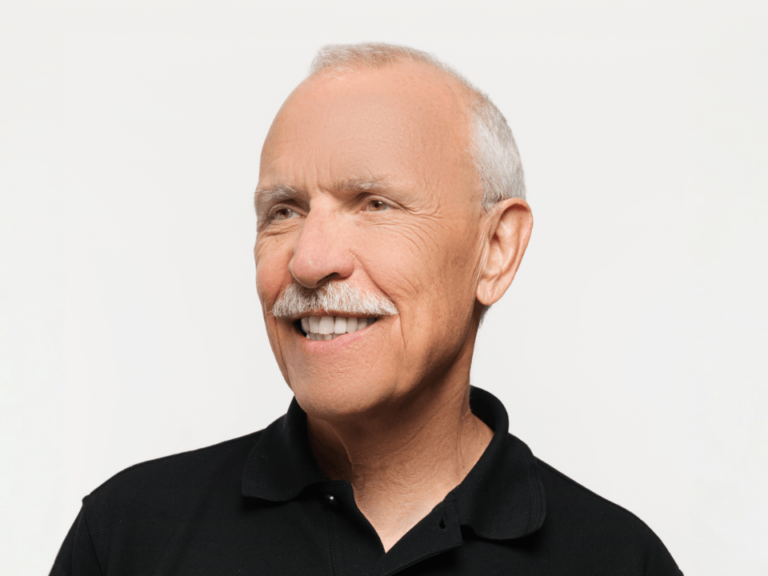

Judd Hollander, senior vice president for health care delivery innovation and associate dean for strategic health initiatives at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University, says the COVID-19 crisis is making it plainly obvious how unprepared the U.S. health infrastructure is for a pandemic.

“This is a bigger problem than just state laws. It deals with federal, state and payer contracting processes,” Hollander, who is also vice chair of finance and health care enterprises in the Department of Emergency Medicine, said to The Cancer Letter. “It is impossible to stand up a disaster response system if you have nothing before there’s a disaster.”

The Cancer Letter asked one large health system, Jefferson, how it uses telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic, how and why these capabilities were developed, and what obstacles need to be overcome.

A related story, a conversation with top executives at Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Jefferson, appears here.

Access to telehealth is particularly important for vulnerable populations, including patients with cancer, who require uninterrupted access to oncologists, for diagnoses, ongoing treatment, and follow-up.

Alas, the slew of systemic barriers inherent to a decentralized, private health care ecosystem means that many provider institutions are scrambling to set up telehealth programs, as states and cities shutter nonessential businesses and issue movement restriction orders and advisories.

Given the dearth of reimbursement and economic incentives, most institutions and oncology practices—even major academic centers—lack robust telehealth programs.

“No one is going to grow a program that costs them a boatload of money—and telemedicine costs a boatload of money—and then not be able to use it to care for their patients,” Hollander said.

“I think from what I know in our local cancer centers, other than ours, very few have telemedicine programs for the reasons I stated,” Hollander said “So, now they’re left with cancer patients—who are most prone to having an adverse outcome from COVID-19—not being able to get their care.

“It’s many, many health systems, regardless. A health system’s incentive is to take care of the patient, but by law, an insurance company’s incentive is shareholder return. So, if an insurance company has a choice to pay or not pay, and they believe the patient’s going to get the care anyway, by law they’re encouraged to not pay.”

Oncologists at Jefferson, for example, through mandates in its telehealth program, are licensed in three states—Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware. This allows patients in the center’s catchment area to receive telehealth visits.

Nevertheless, physicians shouldn’t be required to jump through hoops to reach their patients, Hollander said.

“This is economics for the state. I have 19 state licenses. I pay for each one of them,” Hollander said. “I’ve had to get 11 sets of fingerprints to go to the FBI to verify that I’m not a criminal or a child molester to get those 19 licenses. Now, that’s insane. Can’t they talk to each other?

“The administrative hassles become just brutal for any physician or any administrator to do. And when I’m doing that in the middle of COVID-19, physicians just don’t have time to mess with this stuff. We can’t expand licensing. It has to be easier.”

On March 17, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services expanded telehealth benefits for Medicare beneficiaries—a move that will temporarily allow clinicians to get paid for providing telehealth services.

“Clinicians can bill immediately for dates of service starting March 6, 2020,” CMS said in a statement. “Telehealth services are paid under the Physician Fee Schedule at the same amount as in-person services. Medicare coinsurance and deductible still apply for these services.”

A $2 trillion emergency relief bill passed March 27 by the House of Representatives—which, at this writing, is expected to be immediately signed by President Donald Trump—contains several provisions aimed at improving telehealth: recertification of eligibility for hospice care, reauthorization and expansion of grant programs, deductible waivers for some health plans, as well as enhancing Medicare telehealth services and increasing flexibility.

While laudable, many of these measures are temporary fixes that don’t apply to reimbursement programs and insurers that fall outside of the federal government’s jurisdiction, Hollander said.

“That means Medicare will reimburse, but I have no idea if Blue Cross and Aetna will reimburse me if I’m practicing in a state where they are the payer, but I’m not licensed,” Hollander said. “Or Medicaid as well. Again, a lack of clarity about the meaning of these federal waivers.

“The one message that hasn’t really gotten out there is the fact that these short-term fixes expire, and then they’re not going to leave us in a position to be prepared for the next crisis. We need long-term fixes that solve these problems.”

Hollander spoke with Matthew Ong, associate editor of The Cancer Letter.

Matthew Ong: It seems difficult to believe, in the middle of a pandemic right now, that state laws are making it difficult for your hospital and others to practice telehealth and talk to patients across state lines. What’s happening?

Judd Hollander: This is a bigger problem than just state laws. It deals with federal, state, and payer contracting processes. It is impossible to stand up a disaster response system if you have nothing before there’s a disaster.

Jefferson, actually, despite state requirements and despite poor payer reimbursement stood up a telemedicine program, making us a bit more fleet of foot during these horrible, difficult times. And we did that at a financial loss because we believed that this was going to be medicine in the future, and we would just build the medicine of the future before the future came.

It turns out, although we weren’t smart enough to foresee COVID-19, it was fortuitous that we’re able to scale up in response to COVID-19. That being said, the major state with which we work, outside of Pennsylvania, is New Jersey.

New Jersey, I believe last Thursday night, passed into law that, for the short term patients can see their established provider. So, on Wednesday, if you were a cancer patient in New Jersey, you were not able to see your oncologist in Pennsylvania, which, frankly, made these patients have to travel to get their medical care, when it was the precise thing we were trying to avoid. Right now, that problem is obviated.

On the other hand, technically speaking, if a person is being seen at a Jefferson facility in New Jersey and is diagnosed with a new cancer, my understanding, based on the regulations that were signed into law, they could not see an oncologist in Pennsylvania. This is certainly far from ideal.

They can go to an oncologist in New Jersey, but it might be a generalist, or it might not be somebody with the specific oncologic specialty that they need. So, the law is not perfect, but it’s a heck of a lot better than it was last week.

So, the New Jersey measure still prevents patients from seeking out new providers out of state?

JH: Right. It may fix specialty care with established providers, but it doesn’t allow referrals to oncologic specialists that cater to your type of tumor. So, it decreases the likelihood that people with new cancer diagnoses can get personalized cancer care.

You’ve got a telehealth program, you’ve got relaxed restrictions in New Jersey, but what are some of the other limitations that Jefferson is running into? And how are patients with cancer affected?

JH: The other main limitation is payer reimbursement. And in all fairness to all the payers who weren’t paying for cancer care before COVID-19, they are all transiently paying for cancer care, many of them for 90 days.

There are several problems with that approach. First, this pandemic is probably going to last longer than 90 days. Second, it is likely that something like this is going to happen again. If the payers continue to say that they will stop paying in 90 days, that will also discourage other cancer providers from adopting telehealth plans.

No one is going to grow a program that costs them a boatload of money—and telemedicine costs a boatload of money—and then not be able to use it to care for their patients. People are going to go where the economic incentives are aligned. Right now, the payers are not aligning the incentives such that health systems will establish telemedicine programs.

So, what we’re going to learn in the next three months is that insurance companies are going to make a mint, because they’re not going to be paying for surgery and they’re not going to be paying for in-person care, but they are still going to be collecting premiums. True, they may pay something for some small amount of patients who will be getting telemedicine care, but right now it looks like a lot of premiums collected may remain in their pockets.

In 90 days, according to current policy, many payers are going to stop paying for telemedicine. And if we’re lucky, we’ll be past COVID-19. At that point in time we will have learned that a lot of in-person care can be handled perfectly well via telemedicine.

The unwillingness, at least at the present time, to pay for chronic care, both within and outside of cancer after this 90-day window will mean that, God forbid, COVID-20 happens, we will be no better prepared than we were from COVID-19.

Have all private payers adopted the 90-day timeframe?

JH: It’s just some payers’ individual policies. They all have slightly different policies, but many of the ones that we’re working with expire sometime in June.

That’s my concern. And now the insurance companies will say, “We don’t want to subsidize your telemedicine program,” but you honestly can’t get innovation if it’s not reimbursed. Economic incentives being what they are, people aren’t going to sink a couple million dollars into a program when A, the upfront costs are expensive; and B, the downstream costs aren’t going to be reimbursed.

Is this a problem that is playing out nationwide for any health system that operates across state lines, or deals with any of these issues?

JH: It’s not even across state lines. It’s many, many health systems, regardless. A health system’s incentive is to take care of the patient, but by law, an insurance company’s incentive is shareholder return. So, if an insurance company has a choice to pay or not pay, and they believe the patient’s going to get the care anyway, by law they’re encouraged to not pay.

In my mind, it’s a jigsaw puzzle that just doesn’t come together. There are issues with licensing and problems with all the reimbursement scenarios, exacerbated by different public and private payers and state laws. Where does one start to make amends?

Insurance companies are going to make a mint, because they’re not going to be paying for surgery and they’re not going to be paying for in-person care, but they are still going to be collecting premiums.

JH: Well, you know what? I think that we’ve watched a lot of statements by the administration trying to do the right thing, waiving federal requirements for multiple things. But the things that they’ve waived federal requirements for are often not in the federal domain.

State licensing is a state issue. I’m not a lawyer, but it’s my understanding that the federal government can’t waive that. The individual states need to waive that. Now, it may mean that the OIG is not going to come after you for things during that period, but it might also mean that other state payers are not going to pay you when you practice unlicensed across state lines.

It may also mean that the state can come after providers who practice unlicensed, because licenses are at the state level.

No one knows what it means until the states waive it, because the federal government can waive it, but the states can still enforce it. They could enforce it a year and a half from now. It has created confusion in the middle of a crisis.

So, we’re in a multifaceted quandary and it takes superhuman coordination to make telehealth work in a pandemic?

JH: Yes. If a council of governors agreed to relax the rules—provided you’re licensed in good standing in one state and have never had your license revoked in any other state—to just let you federalize your license and practice across state lines, that would be impactful.

But this is economics for the state. I have 19 state licenses. I pay for each one of them. I’ve had to get 11 sets of fingerprints to go to the FBI to verify that I’m not a criminal or a child molester to get those 19 licenses. Now, that’s insane. Can’t they talk to each other?

And then, actually, if I get licensed in State A on Thursday and State B is going to approve my license on Friday, I now need to get a letter from state A, who just gave me a license 24 hours ago, saying I’m in good standing—before I get a license in state B, and on and on.

And so, the administrative hassles become just brutal for any physician or any administrator to do. And when I’m doing that in the middle of COVID-19, physicians just don’t have time to mess with this stuff. We can’t expand licensing. It has to be easier.

I would ask the question, is there a human being who’s had a license to practice in 10 states, that when they apply for the 11th they get turned down for some reason? I think that’s got to be a trivial fraction of a percent. This process just does not seem efficient.

If I’m not mistaken, CMS expanded telehealth benefits for Medicare. But that only solves one part of the problem, right? Because Medicaid is managed by the states.

JH: Right. So, that means Medicare will reimburse, but I have no idea if Blue Cross and Aetna will reimburse me if I’m practicing in a state where they are the payer, but I’m not licensed. Or Medicaid as well. Again, a lack of clarity about the meaning of these federal waivers.

What about HIPAA compliance? How does that affect, say, the teleconferencing services that you’re able to use?

JH: I think the feds relaxing that is good. I’m very happy they did. What it really does is open up telemedicine capabilities for people that don’t have HIPAA-compliant telemedicine programs.

But what it really can do is it could wreak havoc in a program like Jefferson’s, because we do have HIPAA-compliant telemedicine platforms, and we want to make sure that our providers use HIPAA-compliant telemedicine platforms that meet all state regulatory requirements, and because we don’t want to use something now that won’t be durable for the long-term benefit of our patients.

On the other hand, if the platforms we use now fail, then we have to do what we have to do. And having those requirements relaxed is useful. So, I think relaxing those requirements will improve care for programs and people that haven’t had telemedicine programs. It lets them get up on some things right away. That’s a great, great step.

But it’s not again going to solve a long-term problem. It’s going to just be a short term solution.

How are other providers handling this?

JH: I think from what I know in our local cancer centers, other than ours, very few have telemedicine programs for the reasons I stated. So, now they’re left with cancer patients—who are most prone to having an adverse outcome from COVID-19—not being able to get their care.

Did we miss anything?

JH: I don’t think so. The one message that hasn’t really gotten out there is the fact that these short-term fixes expire, and then they’re not going to leave us in a position to be prepared for the next crisis. We need long-term fixes that solve these problems.