Mountain climber, mentor, swimmer and world-renowned scientist, Beverly Torok-Storb, PhD, a pioneering stem cell biologist who worked at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center for 45 years, died Friday, May 5, at her home in Seattle. She was 75.

A professor in Fred Hutch’s Translational Science and Therapeutics Division, Torok-Storb’s contributions to science and to education in science, technology, engineering and math, or STEM, were substantial and far-reaching.

Torok-Storb, who died on May 5, was a longtime Fred Hutch researcher, mentor and champion of STEM education.

Photo credit: Robert Hood / Fred Hutch News Service

“She was quite a force,” said Fred Hutch Executive Vice President Fred Appelbaum, MD, who started working at the Hutch the same year as Torok-Storb. “She was a very good scientist and very committed to collaboration and training. She was also very interested in the training of junior faculty and students including, importantly, individuals from underserved populations or those that are less represented in science.”

Torok-Storb joined Fred Hutch in 1978 and during her tenure, pioneered lifesaving advances in stem cell research and transplantation biology, winning numerous awards and accolades. Her research had a profound impact on the bone marrow transplant field and helped to save the lives of thousands of people.

But she always had a passion for mentoring and creating career paths into science, especially for those who came from marginalized communities. Her legacy of advocating for education and training will continue through the research internship programs she established at Fred Hutch as well as the two training labs she launched.

‘Teachers turned me onto science’

Torok-Storb grew up in a public housing project in Erie, Pennsylvania, never forgetting her humble roots. Or her teachers.

“I got into science because of Sputnik, the Russian satellite that went into space,” she said in a 2016 interview with Life Science Washington. “It beat our satellite and totally freaked out our government.”

That “freakout” resulted in a renewed focus on math and science education.

“I had phenomenal science teachers in my early days, and they turned me on to science,” she said. “The only reason I made it as far as I did is because of special teachers along the way who let me know that I was capable, and I could do it.”

Photo courtesy of Fred Hutch

After finishing high school, Torok-Storb went on to receive Bachelor of Science and Master of Education degrees from PennWest Edinboro (then Edinboro State College), then pursued a PhD in radiation biology and human genetics from the University of Pittsburgh, studying with bone marrow microenvironment pioneer Dane Boggs, MD, and radiation biologist Sallie Boggs, PhD.

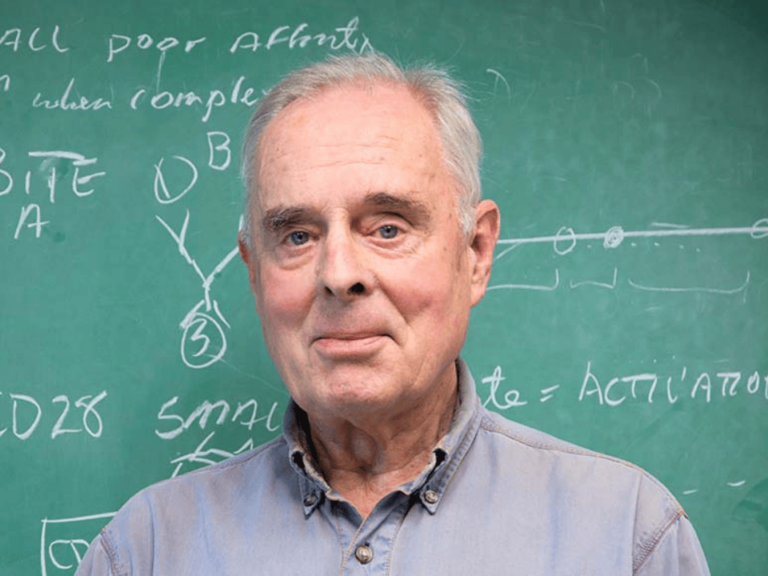

This connection eventually led her to meet Rainer Storb, MD, now a longtime Fred Hutch physician-scientist and Head of the Transplantation Biology Program.

Having been on the receiving end of one of Bev’s calls, I can tell you she was very persuasive. It was easy to get caught up in her enthusiasm. It was clear it came from the heart.

Julie Overbaugh

“Beverly’s mentor, Sallie Boggs, came to see me during a scientific meeting in Seattle in June of 1974,” Storb said via email. “She wanted to discuss experiments and then planned to go water-skiing. Since I’d just bought a condo on the lake in Madison Park, I invited her to come by when she was done. She asked if she could bring several other scientists and her grad student. Beverly happened to be the grad student.”

Storb first laid eyes on his future wife “when she climbed out of the boat and up the ladder to my deck.”

The pair became fast friends. Then Torok-Storb went back to Pittsburgh to finish school and graduate. A year later, she received a National Institutes of Health doctoral fellowship that allowed her to come to Seattle to do research.

“I’d like to say (the move) was motivated entirely by science but it wasn’t,” Torok-Storb said in the Life Science Washington interview. “I wanted to climb mountains. And I wanted to marry Rainer Storb who was in Seattle at the time. So, I came here and that’s what I did.”

Torok-Storb initially worked at the University of Washington in hematology but was intrigued by the work being done by E. Donnall Thomas, MD, and his wife Dottie at Fred Hutch.

“He was working with stem cells—transplanting with stem cells—and I wanted to join his team,” she said. “I was essentially invited to understand why marrow grafts failed when they failed. Why the stem cells weren’t doing their thing.”

Untangling the bone marrow microenvironment

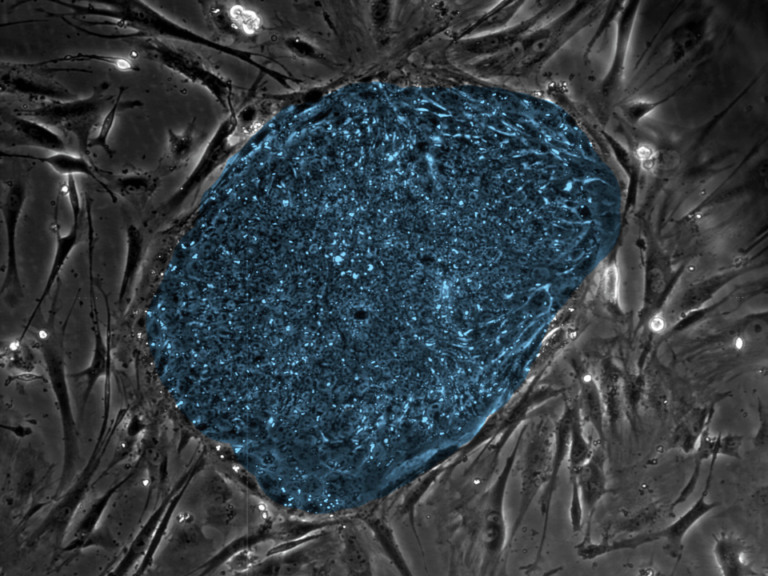

When she joined Fred Hutch in 1978, Torok-Storb continued her studies of bone marrow, and the interactions between blood stem cells — from which oxygen-carrying red blood cells and infection-fighting white blood cells arise — and the supportive cells that make up the bone marrow (or hematopoietic) microenvironment.

“She was really one of the early investigators who understood that there was both a seed — that’s the hematopoietic stem cell — and a soil — that’s the microenvironment — that was necessary for normal hematopoietic function,” said Appelbaum, who holds the Metcalfe Family/Frederick Appelbaum Endowed Chair in Cancer Research.

When Torok-Storb first began studying bone marrow, the “soil,” or supportive cells (also called stromal cells), were dismissed by many researchers as mere scaffolding that physically supported blood stem cells and developing blood cells, said transplantation biologist Marco Mielcarek, MD, who directs Fred Hutch’s Adult Blood and Marrow Transplant Program.

“She had a very different vision of that, and she proved that her vision was actually correct,” he said.

Torok-Storb described this in an interview in 2016.

Photo Credit: Robert Hood / Fred Hutch News Service

“It was an argument I had with lots of big players,” she said. “They believed stem cells had intrinsic control of their fate. I said ‘No, they don’t. They have extrinsic control of their fate. They’re influenced by other cells around them.’ And I was right.”

Mielcarek, who joined Fred Hutch as a postdoctoral fellow in Torok-Storb’s lab in 1994, praised her out-of-the-box thinking.

“Bone marrow is not just some diffuse space where blood-forming stem cells hang out, but actually a highly organized three-dimensional structure that includes many components, including functionally diverse bone marrow stromal cells,” he said. “Beverly and her team did fascinating experiments showing that the normal stroma is not only providing mechanical support, but that these are highly heterogeneous cells that serve different functions.”

‘A rigorous scientist’

Torok-Storb helped to show that stromal cells influence blood stem cells and maturing blood cells through physical support, cell-to-cell contact and secreted molecules. Her work outlined how, rather than being inactive scaffolding, stromal cells are intimately involved in regulating two essential but competing bone marrow needs, Mielcarek said.

Bone marrow must maintain a lifelong pool of stem cells that can produce blood cells — but blood cells also need to mature and take on characteristic functions, a process called differentiation. Torok-Storb demonstrated that stromal cells help maintain the stemness, or self-renewing properties, of stem cells while also helping to orchestrate the development of red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets.

She also was one of the first scientists to show that stromal cells and blood stem cells don’t arise from the same ancestor cell but descend from different cellular lineages.

Photo courtesy of Fred Hutch

Central to her work were stromal cell lines that Torok-Storb created, which allowed her and other scientists studying the bone marrow microenvironment to examine the cells and intercellular interactions in lab dishes.

“She developed systems whereby you could start to take those elements (of seed and soil) apart and put them back together to help us understand how hematopoiesis really worked and why sometimes it didn’t work,” Appelbaum said.

Mielcarek remembers the 27 functionally distinct human marrow stromal cell lines that Torok-Storb and her team developed using human papillomavirus genes to immortalize the cells, and which they shipped nationally or internationally to any scientist who requested them. These cell lines helped Torok-Storb outline different types of stromal cells and the different ways they influence blood stem cells and developing blood cells.

Her work helped reveal how normal bone marrow functions and how interactions between cells can contribute to problems like bone marrow failure, in which a person’s bone marrow does not produce enough red cells, white cells or platelets.

A collaborator and good friend

Her husband, Rainer, who worked in the same realm, said he and his wife collaborated at times, but mainly pursued their own separate research.

“Beverly was always a very independent person and we always tried to keep our research separate from each other,” Storb said in a 2022 interview. “We wouldn’t tell each other how to do experiments, although we did a few pieces of work together and have a number of joint publications.”

Photo courtesy of Dr. Rainer Storb

Storb, who holds the Milton B. Rubin Family Endowed Chair, said they mainly supported each other “through the periods when things don’t work out in the laboratory, talking things through and giving each other encouragement.”

And of course, the pair raised a son, Adrian, who also works at Fred Hutch as a vet tech.

They also co-mentored several postdoctoral fellows, including Mielcarek, who described Torok-Storb as a rigorous scientist, mentor, collaborator and good friend.

“I learned a lot in a short period of time from her,” he said. “I learned how to think critically about scientific questions, how to write succinctly, how to pose scientifically interesting questions and how to discuss them on paper.”

Though laboratory-based, Torok-Storb’s research was always grounded in clinical relevance, said Brenda Sandmaier, MD, deputy director of the recently created Translational Science and Therapeutics Division, or TST. Sandmaier first met Torok-Storb when she joined the Fred Hutch team studying bone marrow transplantation in 1986.

At the time, Torok-Storb was making prominent findings in the areas of bone marrow failure and interactions between stromal cells and bone marrow grafts. Sandmaier remembered that she always made a point of meeting the patients who donated the tissues she worked with.

“She was truly a bench-to-bedside scientist,” Sandmaier said. “There was Dr. Torok-Storb, the scientist, the investigator — but she personalized it.”

‘A soft spot for students and teachers’

In addition to her research contributions, Torok-Storb was the founder and director of Fred Hutch’s Summer High School Internship Program, or SHIP, in which students from diverse backgrounds spend eight weeks on the Fred Hutch campus before the beginning of their senior year, learning research techniques.

She recruited faculty from throughout the Hutch to volunteer as program mentors — one of the reasons the program was so successful.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Rainer Storb

“Having been on the receiving end of one of Bev’s calls, I can tell you she was very persuasive,” said Julie Overbaugh, PhD, a researcher in the Human Biology Division and holder of the Endowed Chair for Graduate Education. “It was easy to get caught up in her enthusiasm. It was clear it came from the heart.”

Torok-Storb started the internship program with four students in 2010. Eight years later, it accommodated 23, thanks to additional funding sources. To date, hundreds of students, many from disadvantaged backgrounds, have participated in the internship program, more than half of them girls. SHIP students have gone on to study at top universities and have been hired by organizations such as NASA, the National Institutes of Health, the Allen Institute for Brain Science, and Fred Hutch.

Torok-Storb also created a SHIP offshoot called the Lead Intern Program, in which five to seven students return for a second summer internship after their senior year. Lead intern duties include assisting with new interns and, in the process, serving as role models and gaining valuable mentorship experience. In 2018, additional funding allowed the program — now known as the Pathways Undergraduate Research Program — to accommodate 22 interns.

Colleagues said Torok-Storb could teach anyone.

“She loved teaching, it didn’t matter who she was teaching,” said Appelbaum, who brought Hutch Award winners and nominees through Torok-Storb’s lab for many years. There, she would “charm the pants off” the baseball players while showing them how to extract strands of DNA from strawberries, he recalled.

Torok-Storb found many ways to connect students to science.

Sandmaier and Mielcarek recalled Torok-Storb organizing lectures in which they shared their work and scientific experiences with high school and college students.

“She made it so we could open up about our story of our academic path, and then listen to the students’ stories, understand what they need, and give them the tools to become successful scientists, or just help them understand research,” Sandmaier said.

Gretchen Johnson, who worked as a technician in Torok-Storb’s lab for nearly 40 years, also praised her mentorship and guidance.

“She was the best mentor anyone could have,” Johnson said. “She had high expectations for teamwork and quality science from her lab and was always there to help you achieve that, word by word, and slide by slide. She had these same passions and expectations for the summer high school interns.”

Even years after their internships, Torok-Storb continues to inspire students.

Jacob Greene, now a medical student at the University of California, San Francisco, was a 2016 SHIP intern and 2017 Lead Intern and Clinical Scholar. He vividly remembers learning about blood cell development from “Dr. Bev.”

“That summer went on to be the singularly most impactful summer of my life,” he said. “Dr. Bev and SHIP allowed me to dream it possible for a kid with cystic fibrosis to pursue a career in medicine … I find the stem cell an appropriate analogy for Dr. Bev’s legacy: Her impact on the development of my life, and that of countless other students, is truly awe inspiring.”

Usman Moazzam, a 2017 SHIP and 2018 Pathway alum, described how Torok-Storb’s guidance extended well past his internship. When Moazzam made the decision to switch majors — from pre-med to computer science — and schools — from the University of Washington to Case Western Reserve University — after his sophomore year, Torok-Storb was there.

“She gave amazing advice that changed my life,” Moazzam said. “Her unyielding support during such a difficult time for me was a blessing and made me even more passionate about the new path I was following.”

Natalie Smith, a 2016 SHIP intern and 2017 Lead Intern and Clinical Scholar, said that Torok-Storb remains a daily inspiration. Smith, who currently works as a clinical research coordinator at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, plans to apply to medical school.

“I am beyond lucky to have gotten to know Dr. Bev and follow in her footsteps as a woman in medicine and science. She has not only had a lasting influence on my career in science but also my life as a survivor of acute myeloid leukemia,” she said.

Dr. Jeanne Chowning, who worked closely with Torok-Storb and counted herself as one of “Dr. Bev’s mentees,” said the researcher had a soft spot not just for her students, but also for teachers.

“She was a natural teacher herself and she recognized it was a great thing to support teachers,” Chowning said. “She was very accomplished professionally, but there was also so much heart in her work. She modelled how those things could coexist.”

Chowning also emphasized how generous Torok-Storb was to her young mentees.

“Her door was always open to students, and she wouldn’t mind them just walking in and chatting,” she said. “She wanted them to feel like they could ask her anything anytime. She was legendary as ‘Dr. Bev.’”

Chowning said that Torok-Storb’s renown extended beyond Fred Hutch and into the Seattle community.

“I heard a story that someone was in an Uber with her once and addressed her as Dr. Bev and the driver had even heard of her,” she said. “He said, ‘You’re Dr. Bev? You’re famous!’”

Torok-Storb, Chowning said, was constantly creating opportunities for people who might not otherwise have them.

“She was just so important to so many—not just to students, but to people across Fred Hutch,” she said. “She’s part of the legacy of our work here. Her scientific achievements were formidable, but her mentorship was unparalleled. She altered the course of my life completely. My career would not be what it is without her and I’m just one of many. I will miss her terribly. Her passing leaves a great void.”

Awards and accolades

The late researcher served as a member of the steering committee for Fred Hutch’s Science Education Partnership for more than 30 years and acted as director for Fred Hutch’s Technology Access Foundation Academy partnership from 2010 to 2017. She was director of the nationally recognized Summer High School Internship Program from 2010 until her death and acted as co-director of the Fred Hutch Clinical Scholars Intern Program from 2017 to 2019.

Her scientific achievements were formidable, but her mentorship was unparalleled. She altered the course of my life completely.

Jeanne Chowning

Torok-Storb published over 150 original papers, served on numerous study sections and scientific advisory committees and brought in many substantial NIH grants during her tenure, including a Pathways to Cancer Research R25; a Frontiers in Cancer Research R25; a Progenitor Cell Biology Consortium UO1 from the National Heart, Blood and Lung Institute; and recently, a $3.2 million Core Center for Stem Cell and Transplantation Biology U54 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, or NIDDK.

She was pivotal in establishing Fred Hutch’s original Co-operative Center of Excellence in Molecular Hematology, funded in 1999 by the NIDDK and still in operation today.

She was selected as a Special Fellow by the Leukemia Society of America for 1979-1981, and received a Young Investigator Award from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute for the same time period.

A longstanding member of the American Society of Hematology, Torok-Storb was the recipient of the Alvin J. Thompson Award for Advancing Science Education and was named Seattle Magazine “Top Doc” for Community Service in 2013.

In 2016, she received the Life Science Innovation Northwest Award and in 2017, she was honored by the Association of Women in Science for Science Outreach.

“She was nominated for the AWIS award by her students,” Chowning said. “So many people have been influenced by her.”

She also received numerous awards for her mentorship including Fred Hutch’s Oliver Press Award for Extraordinary Mentorship in 2019; the UW School of Medicine Award of Excellence for Outstanding Mentorship of Minority Faculty in Medicine and Biomedical Sciences in 2019 and received the Inaugural Humanity in Science Leadership Award from the Fred Hutch Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion in 2021.

‘A force of nature’

Torok-Storb did climb mountains after her move to Seattle, including Mount Rainier. Outdoor interests also included swimming in Lake Washington, and her infectious love of activity carried others along in her wake. Sandmaier and her husband hiked and skied Rainier with Torok-Storb and Rainer Storb, and Torok-Storb’s lab group often enjoyed hiking as a team-building activity.

Mielcarek first met Torok-Storb after she’d just returned, full of energy, from a Swedish Hospital-sponsored aerobics class that met a block away from Fred Hutch’s original First Hill campus.

“A whole group of us from the Hutch would go; sometimes we made up about half the class,” Sandmaier said. “Bev was the ringleader, encouraging us to take that one-hour break in the middle of the day.”

Torok-Storb had energy and enthusiasm for science and for life itself — and was incredibly adept at sharing it with others.

“She was a fantastic writer,” Chowning said. “She was very good at communication. She was just a force. You could not be left unchanged by your experiences with her. As one colleague said, ‘If Bev was in your corner, you felt invincible.’”

Many colleagues, including Clinical Research Division Associate Director Stephanie Lee, MD, MPH, spoke of Torok-Storb’s authenticity and drive. The phrase “force of nature” was used repeatedly.

“She was a huge advocate for people who have not been as lucky in life but have amazing potential,” said Lee, holder of the David and Patricia Giuliani/Oliver Press Endowed Chair in Cancer Research. “And she actually walked the walk. She didn’t just talk about things — she did them. And that was really meaningful. It changed the culture of Fred Hutch.”

Torok-Storb left a great scientific legacy, Lee said, but her legacy also includes what she did for “all the people who were given opportunities they wouldn’t have otherwise had.”

Sandmaier echoed this sentiment. Though Torok-Storb never formally mentored Sandmaier, she served as a role model for the physician-scientist.

“She was an excellent role model for how to navigate being a woman in the late ’80s, early ’90s, in a male-dominated field, but also as a scientist,” Sandmaier said. “She had such an open door: She would mentor even when there was no academic benefit to her.”

Mielcarek and others also appreciated her strong convictions.

“I think it was very important and it was very, very good for an institution to have a voice that questioned certain things and forced discussion,” he said. “By doing that and doing it consistently, by having that type of voice in an institution over decades, it made the institution better and more self-reflecting.”

Appelbaum, too, spoke fondly of her frankness.

“She had strong views and did not hesitate to express them,” he said. “One of the most enjoyable things about it was her frankness and her willingness to sometimes express a contrarian view. But she had the ability to do it in a way that was charming and delightful. I will tell you that being Bev’s boss was like trying to be the boss of a cat. You can’t tell a cat what to do.”

Torok-Storb’s interest in Fred Hutch and its future never waned, Sandmaier said, even as her health declined. She attended every meeting of the fledgling Translational Science and Therapeutics Division in person.

“She always had ideas. She never stopped working toward the future,” Sandmaier said. “She was vibrant and engaged to the end.”

This article was originally published by Fred Hutchingson Cancer Center and is republished with permission.

Diane Mapes is a staff writer at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center. She has written extensively about health issues for NBC News, TODAY, CNN, MSN, Seattle Magazine and other publications. A breast cancer survivor, she blogs at doublewhammied.com and tweets @double_whammied. Email her at dmapes@fredhutch.org.

Sabrina Richards, a staff writer at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, has written about scientific research and the environment for The Scientist and OnEarth Magazine. She has a PhD in immunology from the University of Washington, an MA in journalism and an advanced certificate from the Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program at New York University. Reach her at srichar2@fredhutch.org.