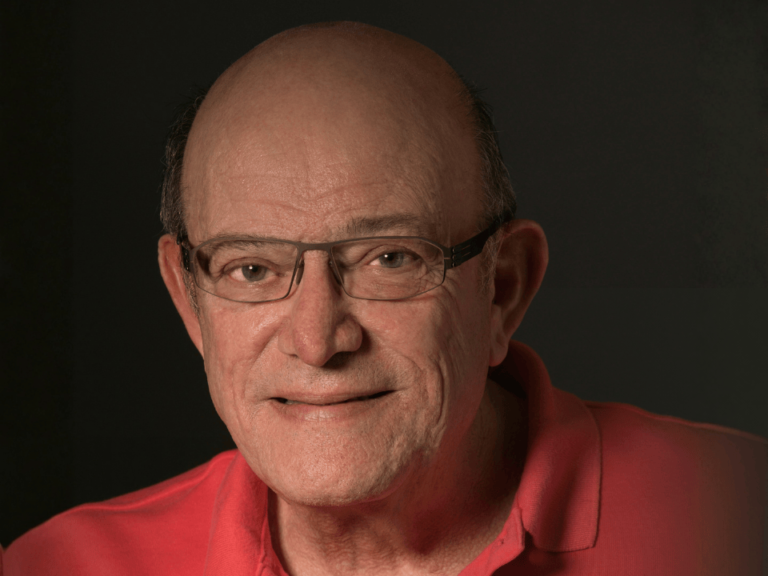

This month on the Cancer History Project Podcast, Melvin J. Silverstein, Medical Director of Hoag Breast Center and the Gross Family Foundation Endowed Chair in Oncoplastic Breast Surgery at USC, sat down with Stacy Wentworth, radiation oncologist and medical historian, to reflect on his career—and founding the first free-standing breast center.

Silverstein founded the Van Nuys Breast Center in 1979. As he saw more and more and more patients with what was only recently coming to be known as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), he wrote the first major textbook on the disease and developed the Van Nuys Classification for Ductal Carcinoma in Situ of the Breast as well as the USC Van Nuys Prognostic Index.

“I became wildly passionate about DCIS. I thought about it all the time,” Silverstein said on the podcast. “I thought about it when I went to sleep.”

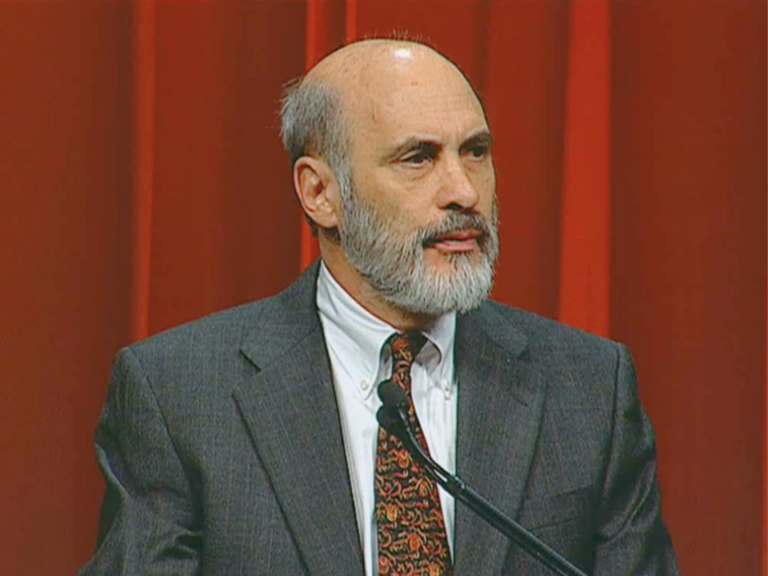

Wentworth, a radiation oncologist at Duke, asked Silverstein about a time when his science was challenged by the medical establishment:

I can tell you as a radiation oncologist, we would have a pro and a con of whether women who underwent breast conservation for DCIS needed radiation. And you have a group of people in the audience, 99% of which are radiation oncologists who at that time are very motivated financially and otherwise to give radiation. And then there would be you or one of your colleagues on stage giving the con that said, “Hey, based on our hundreds of patients over a decade, these women might not need radiation.” Can you sort of talk about that experience? Because I think you were invited to these conferences to fulfill a very specific role.

“Somewhere in the mid-nineties, we came up with the Van Nuys classification, then we came up with the Van Nuys Prognostic Index,” Silverstein said. “And in the end we figured out if you got a low score, it didn’t make any difference whether you got radiation therapy or not. So essentially, small, low grade, well excised tumors didn’t do any better if they got radiotherapy. Maybe they had a teeny bit lower local recurrence rate. There certainly was never any difference in survival. And in fact, nobody’s ever shown any difference in survival, no matter how you treat the disease.”

Silverstein debated against radiation oncologists at conferences for years, and his arguments stirred up visceral responses, he recalls.

“Pro-radiation therapy were all the radiation oncologists from academic centers. That was Jay Harris, who was I guess my arch rival in this. He once, after one of these talks, came up to me, smiled at me and said, ‘You’re killing patients.’ Which broke my heart,” Silverstein said. “It was a terrible thing. He said to me after not giving radiation therapy, but it turns out in the long run, everybody’s come on board. And clearly now it’s 25, 30 years later, some people have finally agreed that they all don’t need it.”

Recent trial results have confirmed Silverstein’s analysis that not all patients with DCIS need radiation.

Today, Silverstein runs the USC breast fellowship program, which has an emphasis on oncoplastic surgery—the first of its kind.

Reflecting on his career, Silverstein offers words of wisdom for early-career clinicians:

It was kind of more important to me, sadly, than children or soccer games or anything else. So I don’t advise that. And I don’t think modern young doctors are like I was. Modern young doctors take time off for the birth of a child. I kind of resented the birth of a child because it made me skip a day of work. So I just came from another time and I’m not happy about it, but I think about this often. If you change any part of your life, you might change where you are now. So if you like what you have now, you’ve got to accept all the terrible things that went on in the past.

Read more on the Cancer History Project. This oral history interview is available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and YouTube.

The Cancer History Project is a free, collaborative archive of oncology history that aims to engage the scientific community and the general public in a dialogue on progress in cancer research and discovery.

This project is made possible with the support of our sponsors: the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, ACT for NIH, UK Markey Cancer Center, Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey/RWJBarnabas Health, The University of Kansas Cancer Center, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

The Cancer History Project is an initiative of The Cancer Letter, and is backed by 60 partners, spanning academic cancer centers, government agencies, advocacy groups, professional societies, and more.

Interested in learning more about the history of oncology? Subscribe to our monthly podcast on Spotify or Apple Podcasts.