I write a weekly blog for Georgetown University’s Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center community. Here I share an updated version of a blog post I wrote in September 2024, now supplemented by some poems I have written over the years that inspired paintings by my wife Harriet Weiner, who is a much better artist than I am a poet or writer.

The title of the blog was “Summer Vacation 2024.” We continue to work on the project and hope to take it on the road when it’s complete. Others will decide if the work is important, but I have long felt compelled to share this defining aspect of my family’s history.

Harriet and I believe it is more important than ever to fight intolerance and its most awful consequences by telling stories that replace grim statistics with names, faces and memories.

Except where noted, all the events described here are true.

It’s a sign of the times that I have hesitated to share this story with a wider audience because it focuses on the very real suffering of Jews during the Holocaust and might be considered tone deaf to the suffering of other historically or currently marginalized groups. However, I decided to proceed because the story would have the same resonance in our own time if the little girl was an unwanted, hunted immigrant in this or any country, or if she was an innocent Palestinian, Uyghur or Ukrainian child suffering from the atrocities that arise from intolerance and conflict.

I do not have the standing or life experience to tell their stories, which I dearly hope will be told.

Hidden child

Most vacations are wonderful. Some are memorable. Only a few are extraordinary. Extraordinary vacations involve life-changing experiences and create enduring memories that alter people and families, leaving imprints on future generations. What follows is a journal of just one day of our family’s extraordinary trip to Belgium in the summer of 2024.

A different kind of vacation

I am the son of a Belgian Holocaust survivor, a hidden child who somehow avoided capture, as did the rest of her immediate family. We lost her to multiple myeloma in 1992. Harriet and I wanted our kids to really understand her history, so we visited some of her hiding places in 1997, escorted by my dad, who knew where some of them were located.

However, on that trip we could not find her most important hiding place, the Groene Villa in Rijmenam, a rural suburb of Brussels.

Exploring our mother’s Holocaust experience has been one of a handful of life-long magnificent obsessions for my younger brother, Steve. He is an authentically sweet human being in the best of ways—deeply empathic, powerfully engaged, always involved in the lives of people he loves—meaning everyone.

He is a clinical psychologist who makes his living doing organizational training for the financial services industry (that is, he humanizes financial advisors for a living). Building on his enduring fascination with history, his doctoral dissertation was on the adult children of Holocaust survivors—in other words, us.

Finally, he is a remarkably talented musical comedy composer, with many wonderful shows and scores in his portfolio. He is nobody’s dope. Most importantly, he is perhaps the finest man I have ever known. We and our families have been each other’s lifelong wingmen.

Harriet and I believe it is more important than ever to fight intolerance and its most awful consequences by telling stories that replace grim statistics with names, faces and memories.

Steve has written a wonderful, deeply researched and moving history of our mother’s experiences as a hidden child, titled “Dearest Ones.” He has nurtured meaningful connections with our Belgian family members and with many Belgian people with a connection to the Holocaust and its aftermath.

A few years ago, I began to write a series of poems that reflect on many of our mom’s stories that he describes in his book. Finally, Harriet and I have embarked on an ekphrastic collaboration where her paintings are visual reflections on my poetry.

For all these reasons, a trip to Belgium made a lot of sense for us.

For Steve’s birthday in December 2023, I had told him I would take him to the World War II Museum in New Orleans. For him, both time and history stopped in 1945, when World War II and the Jewish Holocaust ended. As the year passed, we realized that he was going to England to reconnect with his buddies from his junior year abroad at the University of Nottingham.

He suggested that we meet in Belgium to retrace some of our mom’s steps and visit our remaining family. I said that I would cover his costs in Belgium instead of New Orleans. It was a no-brainer.

Our first cousin, who is my age, has had a terrible past few years. First, she lost her husband, and then was diagnosed with Stage III colon cancer, which was treated with surgery and then adjuvant chemotherapy with FOLFOX, which knocked her socks off.

Unfortunately, her CEA tumor marker never really dropped, and she was found to have a large, solitary liver metastasis. I had her see a leading colon cancer authority in Brussels. Eventually, she underwent a partial hepatectomy, followed by additional chemotherapy that wore her down, with profound loss of appetite and weight loss.

Steve and I decided to see her because, while she has a chance to be cured, I know all too well that it does not always end well. Ironically, as we were traveling, one of my favorite patients, only 56 years old, fighting metastatic colon cancer for the past five years, was nearing the end of his cancer journey, wracked with pain and mourning the looming end of his life.

It was important to see our cousin now.

The kindness of others

So, we made our arrangements. We decided to take our oldest grandson, Isaac, a whip-smart 13-year-old, as a bar mitzvah gift.

He read my brother’s self-published book about my mom’s experiences during the Holocaust, taught himself nearly fluent conversational French, and was excited to join us not only for the history but for the chance to meet new members of his family.

His mom, Elana, a mathematician and prominent cancer researcher at the University of Maryland, decided to join us. Her husband, Ben and their other two kids stayed behind, as did our other two kids and their families. If our finances and health hold up, we hope to have similar trips to Belgium with all our grandchildren as they become “of age.”

We booked a stay at the Marriott Grand Place in Brussels. We had an uneventful flight, spent a few days in Brussels, and had a wonderful visit with our cousin and her family. Up to that point the first four days of our vacation had been upbeat. Then came the day I will remember for the rest of my life.

Steve—to be known moving forward as “Dr. Holocaust Vacation” arranged the day for us. After breakfast, we took a brief walk and then drove to Rijmenam to meet the 91-year-old niece of the man who hid my mother’s family when they first went into hiding.

Our grandfather, seeing the arrests and deportations of Jews in Brussels nearing the end of 1942, approached his two best non-Jewish customers (he sold leather goods) to see if they could help. One of them promptly denounced them. The other one had a country home in the then-distant Brussels suburb of Rijmenam and offered to rent it to him.

Having been denounced, our mother and her family escaped that same day with only the clothes on their backs. The family departed Brussels one by one on separate trolleys, to avoid a group capture.

My mother went last. While on the trolley, a German officer motioned her over and made the terrified 12-year-old girl sit on his lap. He told her she reminded him of his daughter and then left her alone.

The family hid in that house, going out pretty much only at night, dependent on the kindness of others for food and other necessities. They were living in proximity to the town of Mechelen (Malines in French), which was home to the train station that served as a major deportation center of Jews to Auschwitz.

My grandfather made leather goods in the house that the family’s protector then sold as a way to pay rent.

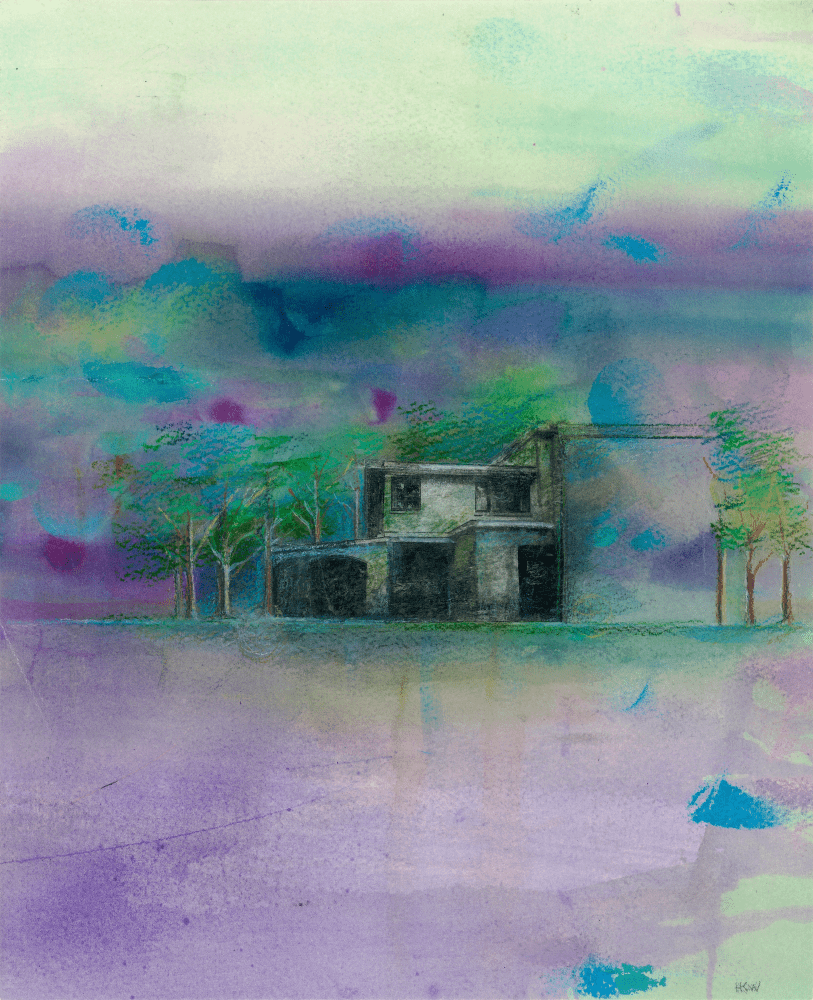

As part of our ekphrastic collaboration I imagined my 12-year old mother in the kitchen of the house, known as the Groene Villa, just after she had arrived. Harriet’s painting reflects on the poem I wrote, and touches on some of the visual and poetic themes that follow.

1942, Belgium

Innumerable stars, each with untold possibilities.

Some support life, sustaining their planetary offspring.

Some glow without apparent purpose, others cool down,

oozing interstellar life, without consequences.

Still others shine, overly bright, expanding to destroy

everything in their paths with indifferent exuberance.

Unseen black holes, galactic quicksand, attract and destroy.

Some stars, mere symbols, mark their targets for death.

On a starry cloudless night, with a slight chill in the air,

she turned on the stove to heat up the soup.

A comforting, familiar faint scent of gas filled the room.

As the soup bubbled in the background, she sat down

To do homework her teacher would never see.

Harriet Weiner

11” x 14”

Oil on canvas

We wondered how she felt as a child about being a target for persecution, in the following ekphrastic collaboration, titled “Six Points.”

Six Points

On that clear cloudless night she saw a billion lights.

Each a message from the distant past, carrying its

story—unique, timeless, important, eternal.

Each one different, perhaps. But so similar.

She squinted, but each night star seemed round.

Her girlfriend’s Christmas tree had a star on top.

Five points, not round. A star devised by man.

She looked at the star on her sleeve. Six points.

She did not understand stars with points.

Real stars are round balls of gas that burn

to create life, sometimes, or to consume it.

But stars with points cut, they cause pain.

She looked back at the night sky, asking each star,

What is your story? Do you still burn bright?

Did you fulfill your destiny? Did you have a future?

My star tells me that my flame will soon be gone.

Harriet Weiner

19” x 12”

Watercolor on 140 lb paper

As reports of denunciations and deportations intensified, my then 13-year-old mother eventually left this house and went into hiding in other safe houses, and even in a convent in and around the environs of Liège, which is in the southeast part of Belgium, north of the Ardennes.

Her parents and sister stayed behind; her sister’s boyfriend and future husband was hiding nearby. But without the kindness of their protector, she would have been nothing more than another grim statistic, and we, our children and grandchildren would have never existed.

Hiding in plain sight

With the help of the Resistance, she went to a convent, where only the Mother Superior knew she was Jewish.

She hid there for about a month before she moved on, because she was the only novice who never had visitors, and the nuns were getting suspicious. She ended up in numerous safe houses thereafter where strangers risked their lives to save her.

In 1944, she was running an errand for her hosts when an Allied bombing raid targeted a nearby bridge that was used to supply German troops with reinforcements and equipment for the Battle of the Bulge.

She ran towards a house, knocked on the door and, as was the custom of the day, was allowed to hide in the cellar. To her horror, three German soldiers who were also seeking shelter clambered down the stairs. The following poem describes what happened.

Holy Deception

Peril remained, so she never saw her family, shuttling from

one safe place to another. As the Resistance grew stronger,

she saw the light, running errands for her hosts. One day

the bombers came at noon to knock out the bridges.

She ran to the nearest house, knocked on the door

and hid in the cellar, awaiting her fate.

A knock on the cellar door. In came three German soldiers.

They too hid from the bombs, waiting, frightened.

They were trained to sniff out people like her,

even innocent children old before their time.

She was 15. She knew what she had to do.

She reached into her purse, and pulled out

the rosary beads she kept for such an occasion.

A trained novice, she led them in prayers.

As it rained bombs, they trembled in fear, together.

The raid ended, and they all went about their days.

So alike, so different.

Harriet Weiner

9” x 12”

Watercolor on 140 lb paper

The Hebrew prayer for peace in the painting translates as “May the One makes peace in the high heavens, make peace for us and for all Israel.”

So, that convent saved my mother’s life twice—once when she hid there, and then because she learned enough Catholic ritual to save herself when she faced capture and near-certain death.

When I accepted the position as director of Georgetown’s Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center at the end of 2007, many of my Jewish friends asked me why I would choose to work at a Catholic University. I had a simple answer.

If that Mother Superior was willing to save a little Jewish girl’s life at great personal peril, then this great university was good enough for me. It was true then, and it has remained so to this day.

The Groene Villa

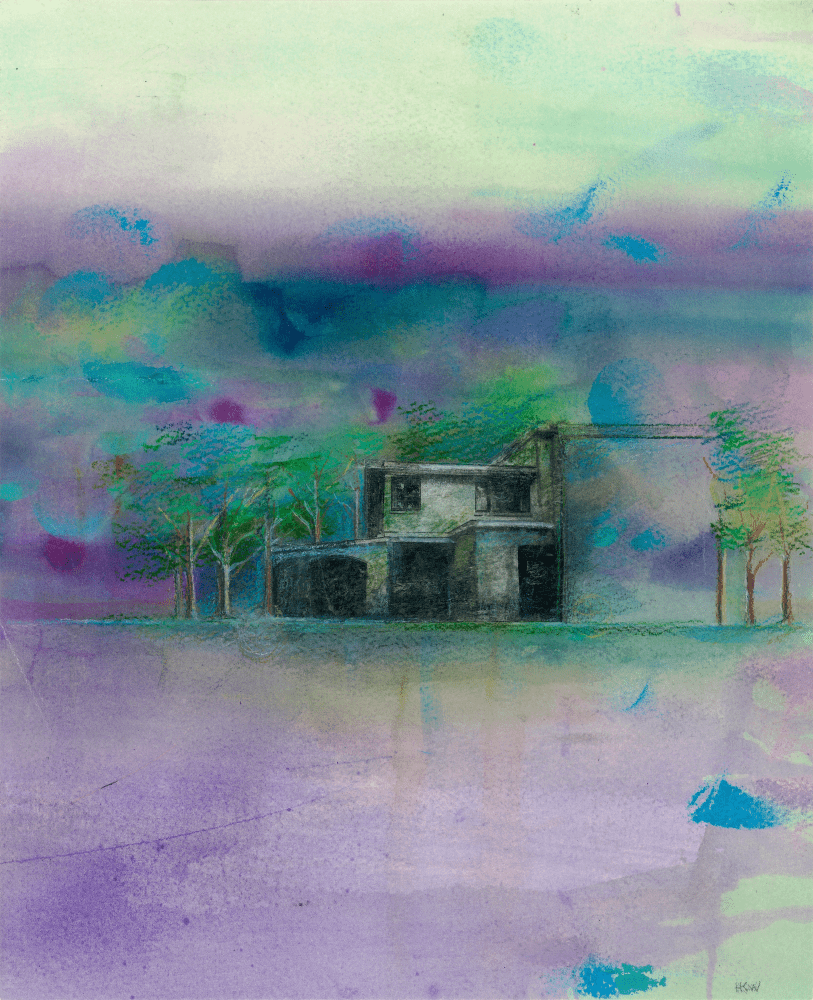

It was time to finally catch the Weiner family’s Great White Whale. It was especially powerful and poignant to go to the house—the Groene Villa (it was covered in moss and painted green at the time of the war)—to walk where she once walked, to try to imagine how she must have felt, and most importantly, to share our gratitude with descendants of a man who literally risked his own life to save an innocent family and make our lives possible.

Similar remarkable acts of grace and courage happened throughout Belgium, enabling nearly half of its Jewish population to survive the Holocaust.

We got to the house at 11 a.m. It continues to be in a remote location and is modest in its dimensions and furnishings. Still very much a country home designed as a weekend getaway by its original builder, it now is painted white, has a more modern addition, and for many years was inhabited by the 91-year old niece of my family’s protector. Her nephew now lives in it, and she lives independently in a small cottage on the property.

We met her—a remarkably active and physically robust woman who prepared a lovely lunch for us. We were joined by her niece, who works as a lawyer, and her two grandnephews, one a classical musician and another in college. The two of them share an apartment in Amsterdam and came in to meet us.

This was a remarkable moment for us, but I think it resonated just as deeply for our hosts. Just as we have our family legends, they have theirs, and I suspect that we were the physical manifestations of their stories. I felt my mother’s presence on the property as we sat and talked and wondered what she, my grandparents, and aunt, would think of our being in this spot. Would it have been too painful for them to contemplate?

Below is another ekphrastic work, entitled “Lunch at the Groene Villa.” We titled the paintings “The Groene Villa” and “Hidden Child.”

Harriet Weiner

11” x 14”

Watercolor on 300 lb Arches Paper

Lunch at the Groene Villa

It took 82 years to prepare the lunch.

We went to Belgium to see the family

And search for clues to her past.

How she made it through Hell

And how we came to be.

We were a motley three generation crew –

Our 13-year-old grandson,

His mother, my brother and my wife,

In search of answers at the Groene Villa,

Our family’s great white whale

A kind man gave shelter to her family

At great risk, and they arrived on the day

They were denounced, one by one—by trolley.

There they stayed, hidden, helped

Until she fled, never to return.

It is no longer green, and there are updates,

but in many ways it is unchanged.

His niece made us lunch, joined by

Some of her family. Our story is their story too.

We celebrated this righteous man, that little girl.

We sat around the modest table, four generations

Chatting with the warmth and familiarity

That comes with adjacent memories and time.

In the corner of my mind’s eye a teary-eyed little girl,

Impossibly old, sat at that table, looking at us—at me.

She smiled, nodded and silently whispered, “Ya, Ya.”

Unsurprisingly, we bonded quickly around our shared histories and our hopes for a better future. I felt an emotional high, the untying of a lifelong, stubborn knot, as we hugged and then departed for a far more sobering experience.

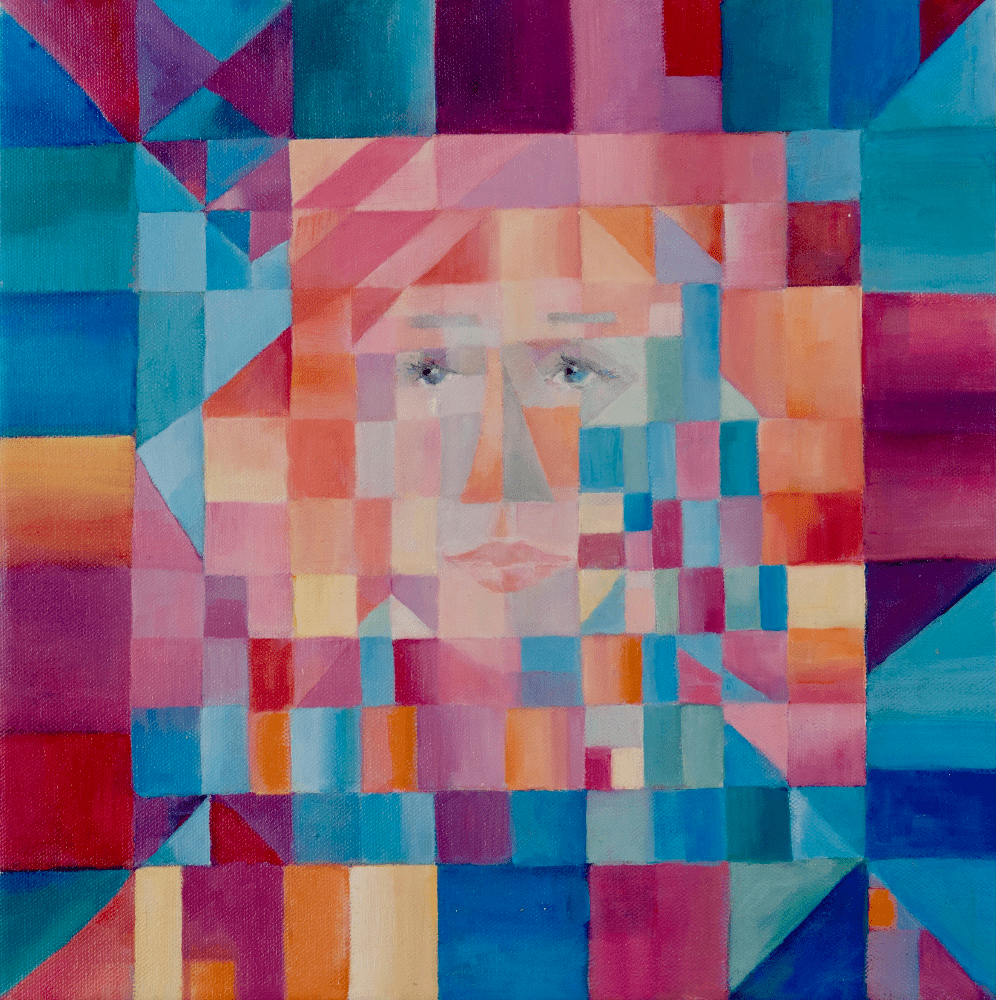

Harriet Weiner

14.5” x 14.5”

Oil on canvas

The gate to hell

We drove from Rijmenam to the Kazerne Dossin, the Jewish Holocaust Memorial in Mechelen. I have been to Holocaust museums that describe what happened, who it happened to and who made it happen, explain how it happened and challenge us to consider what it all means. I have visited Dachau, where it happened. But that bleak killing ground did not put faces to the numbers.

Kazerne Dossin (Barracks Design in Dutch) is where the lives of many thousands of innocents, both ordinary and extraordinary, changed in a flash. It is where they were housed in inhuman conditions for times ranging from a few days to a few months before they were transported by cattle car (one of which is adjacent to the courtyard) to be murdered at Auschwitz and elsewhere.

Kazerne Dossin is now a museum, and Steve had been in contact with its director, who, since we had been delayed by lunch, apologized for not being able to meet us. Instead, we were met by the museum’s archivist, who was waiting for us, as we had a job to do. We took a tour, learned that some of the sadistic jailers had been executed after the war, and that the barracks had been converted for years into apartments before it became a museum.

The walls of the main exhibition space are covered with the digitized photographs, names and ages of the doomed, with other artifacts such as letters, marriage certificates and occasional religious pieces such as menorahs. An interactive video display allows one to search for and find anybody who had passed through there on their ways to their executions.

It was there that I met some members of my family for the first time. We found three of them—a 48-year-old great-uncle, his 31-year-old wife and their 10—yes, 10-year-old—daughter, saw their pictures and mourned their deaths.

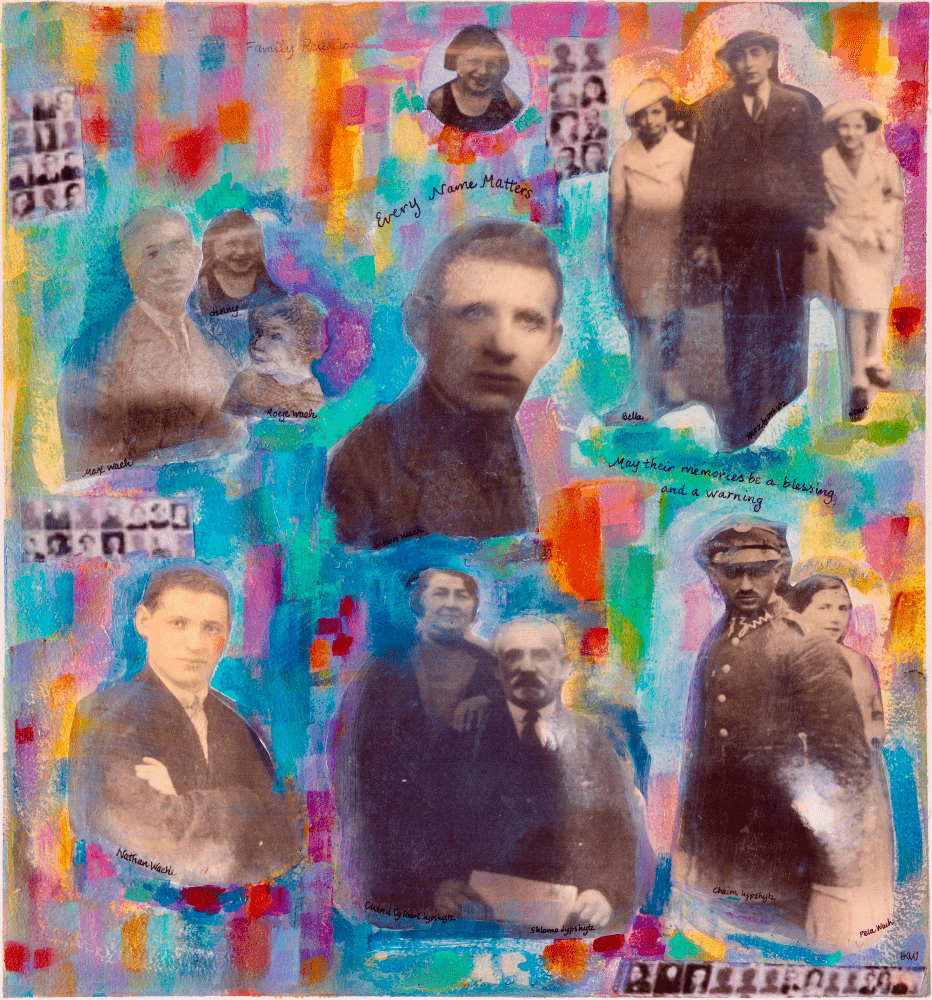

Family Reunion

We drove to Mechelen, an unassuming town with a terrible past,

To visit the Kazerne Dossin, a deportation center in the town

Where lambs were warehoused for a few days or a few months

On their last journeys to the camps and incineration.

Countless thousands, each one was photographed and catalogued

With morbid Nazi precision

The Kazerne Dossin. It was an actual portal to Hell on earth.

Everyone knew what it was, where it was, and what it meant.

It was perhaps ten miles away from where she hid, but

It was never far from her thoughts. Fear burned through her

And scarred her for life.

Its unspeakable atrocities were merely a prelude to the main event.

But after the war the Commandant and several senior sadists

Were tried, sentenced and executed. Few cried for them.

The prison was converted into an apartment block.

Oh, if those haunted walls could talk!

It then became the Belgian Holocaust Museum, replete with a cattle car

On the train tracks with only one destination – Auschwitz.

We toured the museum, its main hall covered with the digitized photos,

Names and ages of every victim, each staring into a camera for the last time.

We searched the database for her family name, and there we found them.

My great uncle, his wife and their 10-year-old daughter. All lost. Until now.

We went down to the recording studio, and there my brother

Read their names aloud, for posterity, his voice and their names,

In a perpetual roll call, so that they will not be forgotten.

May their memories be a blessing – and a warning.

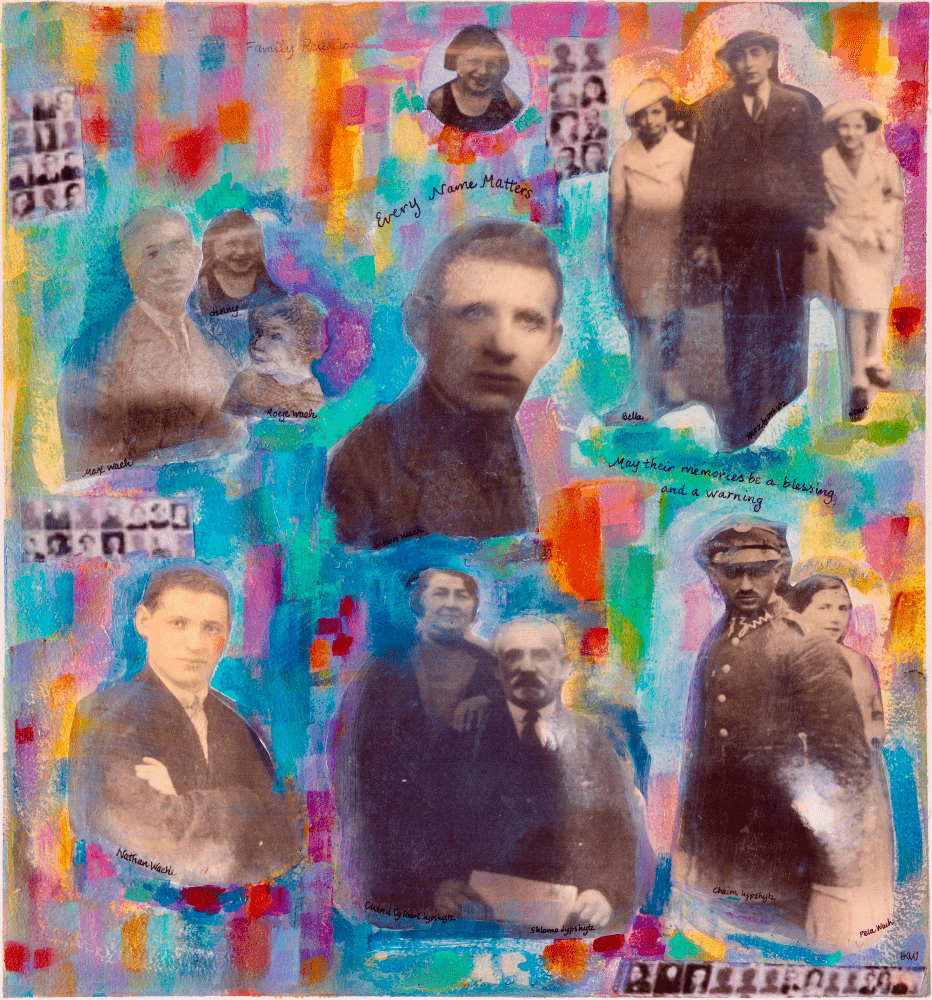

Harriet Weiner

20” x 18”

Watercolor and mixed media on 300 lb Arches paper

Photos of some of Lou’s European family members, nearly all of whom perished in the Holocaust. The little girl (top middle) was his mother’s 10-year-old cousin who, with her parents, hid briefly at the Groene Villa with his mother’s family. They then returned to Brussels, where they were promptly arrested, deported via the Kazerne Dossin and murdered at Auschwitz. Lou’s mother is at the top right of the picture.

We then saw additional exhibits, one of which runs continuous audio loops of the names and ages of the victims, recited by their surviving family members and descendants, so that their memories remain tangible. We were escorted to a recording studio where Steve recited their names and ages for posterity.

The next room was devoted to the children—so many of them, so young, all denied their futures: robbed of the children they would never have, and of the myriad opportunities they might have seized to make the world a better place.

The last room we saw was devoted to a video interview of an elderly Belgian man, one of the very rare Auschwitz survivors, describing the last time he saw his wife and his three little children when their train arrived at the death camp on the way to their murders.

There was nothing more to say, nothing left to feel. We left the museum, surprising our guide, who wanted to show us everything. Steve was anxious to stay, but for the rest of us, all our pieces had been broken and we needed time to reassemble them.

A happier reunion

We drove back to Brussels. The car was quiet as we drove through the rain (the only rain we experienced that week). We had dinner plans that evening with my second cousin, his wife, their son and his girlfriend. He is the son of my mother’s cousin Ginette; during the war my mother somehow learned that Ginette and her younger brother Willy, 9- and 7-year-old children, had been captured and were in a detention and deportation center in Brussels. Their parents could not find them. My mother got word to her father, through a letter that we still have. He alerted the Resistance, who rescued the children. They traveled to the U.S. for my mother’s funeral in 1992 and lived long, productive lives.

My cousin is a musician and photographer, and his wife is an attorney whose clients include the estate of the great Belgian artist René Magritte. Their son and his girlfriend are physicists who study quantum mechanics in Germany (proof that change is possible).

We had a great meal together, highlighted by fascinating conversations, enormous warmth, fine wine and a fabulous homemade lasagna. We celebrated my mother’s courage, resourcefulness and extraordinarily good fortune. We brought a cake that Steve and Isaac had purchased at Le Pain Quotidien near the Grande Place in Brussels (it is a Belgian chain with many shops in the U.S.—I did not have the heart to tell Steve that), and our hosts graciously accepted and served our gift for dessert.

Elana quickly bonded with the two physicists over data science and quantum mechanics. Isaac’s surprisingly deep understanding of history and politics made him a valuable and exuberant contributor to our conversations.

Our cousins described the increasingly precarious situation for Jews in contemporary Belgium, with police protection for all synagogues and religious schools, outright antisemitism in the media and popular culture, and growing violence.

They are sophisticated and fundamentally balanced people and are not at all alarmist, but they have purchased a property in Costa Rica that they use for vacations and as a possible “safe haven” should the unthinkable happen again, albeit in a different form.

We took an Uber back to the hotel, exhausted, haunted, exhilarated and a bit overwhelmed by a day like no other.

Postscript

I may never fully process all that happened on that day. It is a miracle that I exist at all. I remain troubled and deeply saddened by the extraordinary capacity of humans to hate and kill.

I have worn the burden of my mother’s story like a weighted vest throughout my life. Her story, and that of so many others, amplified by a wider recognition of the horrors of the Holocaust, only briefly muffled the shrill sounds of barbarism and intolerance, be it against Jews or any other marginalized group. Hate is a light sleeper.

I worry for the future, yet retain a basic optimism, because my mother and her family survived through the intercession of a series of righteous people, many of them strangers. There will be others who answer the call when asked. If needed, I will be one of them. Thus, I hope. I will not despair.