The Cancer History Project preserves legacies, stories, and transcripts.

In 2022 the Cancer History Project:

- Published interviews with survivors of cancer to record what it was like to be diagnosed with cancer in the 1960s, 1990s, and the 2010s,

- Collected oral histories, including never-before-published interview transcripts with Donald Pinkel, James and Jimmie Holland, and Lucius Sinks,

- Published foundational texts in oncology, collated educational resources, and

- Hosted a series of panels on oncology’s most pressing issues.

The Cancer History Project is making these stories even more accessible with the Cancer History Project podcast—available anywhere you listen to podcasts—an ongoing panel series, and continuing opportunities for experts to lead as guest editors.

The Cancer History Project Podcast

On Feb. 11, the Cancer History Project published its first podcast episode, a conversation with Harold Freeman—the father of patient navigation.

This episode, now the podcast’s top episode of the year, opens with Freeman’s emotional recollection of his early days as a physician:

I’m ready to cut cancer out of Harlem. I’m ready to do it. I’m skilled. I know how to cut cancer out. I want to cut it out of Harlem.

I can’t do that. I can’t cut it out. It won’t yield. It won’t yield to the surgeon’s knife. Cancer wouldn’t yield. So now I’m frustrated. I said, “I got all this skill. I can cut this thing out.”

But then I get to the reality, I can’t cut it out.

Why? Because the people were coming in too late with cancer for me to be able to cut it out.

Now with 787 minutes of new content on the history of oncology, the Cancer History Project podcast is ranked in the top 25% most followed podcasts and the top 30% most shared globally, according to Spotify wrapped.

Recent episode highlights:

- Craig Jordan on discovering tamoxifen’s role in breast cancer and a lifetime of innovation

- Robin Scheffler on viral oncology’s complicated path

- Dwight Tosh, the 17th patient at St. Jude, on surviving lymphoma in 1962

- Susan Love: Breast cancer activism in the 1990s

17

Episodes

787

Minutes

15

Countries

Contributors

The Cancer History Project, with its 56 institutional contributors who are dedicated to preserving oncology’s history, continues to be a valuable resource.

The most prolific contributors of 2022 have published oral histories, profiles, videos, podcasts, and obituaries as part of this continued project.

The contributors who published the most in 2022 are:

If you would like your institution to become a contributor of the Cancer History Project, contact admin@cancerhistoryproject.com.

Interested in learning more and following this project?

Sign up here to hear from us about the latest articles and events, as well as editorial, advertising, and sponsorship opportunities.

Top 25 most-read articles in 2022:

1

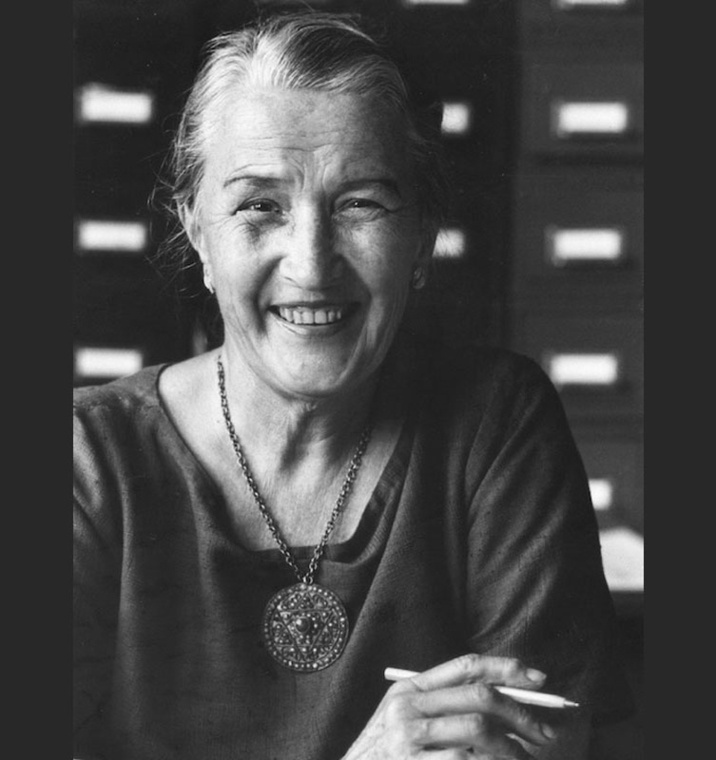

Remembering Jane Cooke Wright, a Black woman, who was among seven founders of ASCO

By Edith P. Mitchell, MD | Feb. 19, 2021

Edith Mitchell: It is a great privilege and honor to have the opportunity to represent the National Medical Association in this tribute to Dr. Jane Cooke Wright. I first met Dr. Wright during an ASCO meeting and maintained subsequent contact.

She is affectionately known in the cancer research community as the Mother of Chemotherapy. She is not only known as the Mother of Chemotherapy, but Dr. Wright is listed in the Women Pioneers of Medical Research and among the top Medical Researchers.

As a researcher, physician, administrator, teacher, mentor, educator, her many discoveries have brought continued health into the lives of millions of people. Across the board, doctors and research scientists dedicated themselves to find cures and treatment for some of the most severe and significant diseases that have challenged mankind for many ages.

Related:

- Jane Cooke Wright: Personal photographs, Feb. 19, 2021

2

Book: Simone’s Maxims: Understanding Today’s Academic Medical Centers

By Joseph V. Simone, made available through his estate | Jan. 29, 2021

Joseph V. Simone, a visionary physician-scientist and writer of guidelines and maxims, died on Jan. 21. He was 85.

To celebrate Joe’s life, his family is allowing The Cancer Letter and the Cancer History Project to make Simone’s Maxims available in electronic form. The book continues to be available in paperback from Editorial Rx Press.

“Simone’s Maxims” is a book so fundamental to academic oncology that we don’t know when we are stealing Joe’s lines.

3

Video: Padmanee Sharma on coming to America and falling in love with science

By Jim Allison: Breakthrough | April 1, 2021

Dr. Padmanee Sharma discusses her childhood, immigration to the United States, and how she found her path into science.

Archival footage from filming Jim Allison: Breakthrough.

4

Panel: Black History Month panel: “We need to talk about justice”

By Cancer History Project | Feb. 25, 2022

A panel convened by the Cancer History Project for Black History Month started with a discussion of mentorship, and concluded with a big underlying concept—justice.

The panel, which met Feb. 23 at 7 p.m., included:

- Robert A. Winn, MD

Guest editor, Cancer History Project;

Director and Lipman Chair in Oncology, VCU Massey Cancer Center;

Senior associate dean for cancer innovation and professor of pulmonary disease and critical care medicine, VCU School of Medicine - Otis W. Brawley, MD

Co-editor, Cancer History Project;

Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Oncology and Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins University - Edith P. Mitchell, MD

Member, President’s Cancer Panel;

Clinical professor of medicine and medical oncology,

Department of Medical Oncology;

Director, Center to Eliminate Cancer Disparities;

Associate director, diversity affairs;

Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Jefferson, Thomas Jefferson University - John H. Stewart, MD, MBA

Professor of surgery, Section of Surgical Oncology;

Founding director, LSU Health/LCMC Health Cancer Center

5

Lucius Sinks: 2013-2015 interview transcripts

By Tim Wendel | June 10, 2022

The following interview notes were created by Tim Wendel, lecturer at Johns Hopkins University, in the process of writing his book, “Cancer Crossings: A Brother, His Doctors, and the Quest for a Cure to Childhood Leukemia.” Wendel is a member of the Cancer History Project editorial board.

Wendel’s brother sought treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Sinks was his doctor.

Wendel conducted several interviews with members of the ALGB, or Acute Leukemia Group B, including Donald Pinkel, James and Jimmie Holland, Jerry Yates, James Holland, Emil “Tom” Frei, and Emil J. Freireich. Considered “cancer cowboys” of the time, this group of doctors sought to treat and cure childhood leukemia, which Wendel’s brother died of in 1973, at a time when the survival rate was about 10%.

6

Remembering the “Murderers’ Row” at Fox Chase’s Institute for Cancer Research

By Jonathan Chernoff, MD, PhD | May 20, 2022

The Institute for Cancer Research (ICR) was and is a hotbed for basic and translational discovery. Initially a standalone institute, the ICR is currently the main science engine for the Fox Chase Cancer Center.

Despite its modest size and budget, ICR, which thrives on small-scale, old-school science in the best sense of those terms, has historically punched well above its weight. This is due largely to its ability to attract top talent. Starting in the late 1960s, Tim Talbot, the longtime scientific director, had the wit and the means to assemble a veritable “Murderers’ Row” of cutting-edge cancer researchers that set the tone for the ICR for decades to come.

What he offered these scientists wasn’t so much better money, more modern equipment, or roomier space, though he did offer some of that. No, the real draw was the chance for these advanced thinkers to realize their dreams, unfettered by other institutional responsibilities, and to work alongside an absolutely stellar group of creative people who, over time, have had an outsized impact on our understanding of the genetic and cellular bases of tumorigenesis.

Related:

- Photo archive: Fox Chase Cancer Center’s “Murderers’ Row”, by Fox Chase Cancer Center, May 20, 2022

7

Podcast: Edith Mitchell on her path from Tennessee farm to becoming a cancer doctor and brigadier general

By Cancer History Project | Feb. 18, 2022

Edith Mitchell came a long way from growing up on a Tennessee farm, to becoming a brigadier general and serving on the President’s Cancer Panel.

“It was making a plan, having a plan, and all of us had similar type plans that we needed to leave the farm—yes I grew up on a farm—and get out of town,” Mitchell, member of the President’s Cancer Panel, clinical professor of medicine and medical oncology, director of the Center to Eliminate Cancer Disparities, and associate director of diversity affairs at Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Jefferson, Thomas Jefferson University. “Yes, you have success, but look back and pull somebody behind you, pull them up.”

Mitchell spoke with Robert Winn, director of VCU Massey Cancer Center, and John Stewart, founding director of LSU Health/LCMC Health Cancer Center.

8

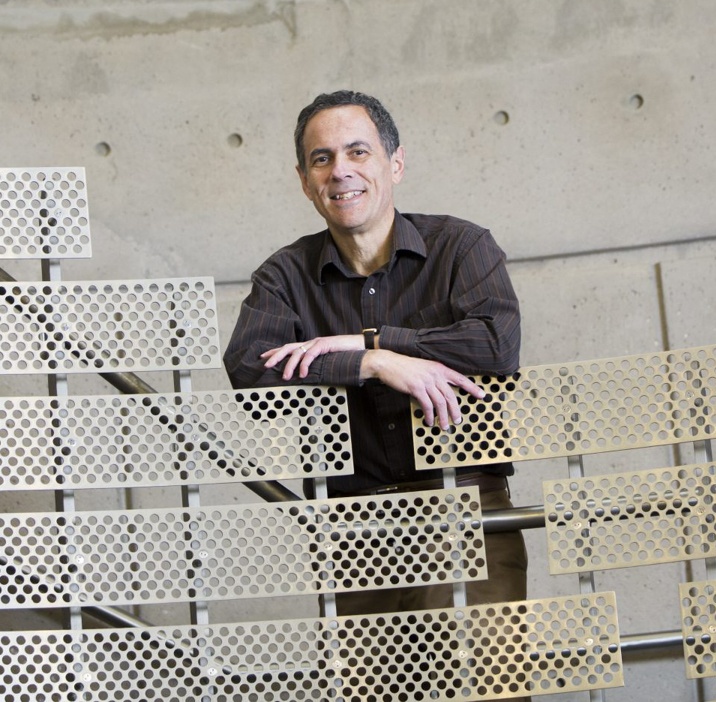

Coal Miner’s Son: Dr. Dennis Slamon

By UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center | Feb. 17, 2021

It is roughly 2,500 miles from New Castle, Pennsylvania, to Los Angeles, California, but distance alone doesn’t define how far the two communities are apart. New Castle is a mill town that was known as the tinplate capital of the world in the early 1900s. L.A. is … L.A. Yet, UCLA’s Dennis J. Slamon, MD (FEL ’82), PhD, the 2019 recipient of the Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award—widely regarded as America’s top biomedical research honor—really hasn’t strayed far from his roots. His father, uncle, and grandfather all were coal miners in West Virginia before Dr. Slamon’s parents moved to New Castle, where Dr. Slamon was born. Dr. Slamon choose to mine a different vein: data.

It is his belief in data and a dogged perseverance that led Dr. Slamon, professor and chief of hematology/oncology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, to the groundbreaking development of the breast cancer drug Herceptin, a lifesaving monoclonal antibody for women with HER2-positive breast cancer, a particularly aggressive form of the disease. Monoclonal antibodies are proteins created in a lab that, when injected into humans, bind to and destroy specific invader organisms like cancer cells. He shares the award with H. Michael Shepard, PhD, an American cancer researcher then working at the biotechnology company Genentech, and Axel Ullrich, PhD, a German cancer researcher also formerly of Genentech and now at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry outside of Munich, Germany.

9

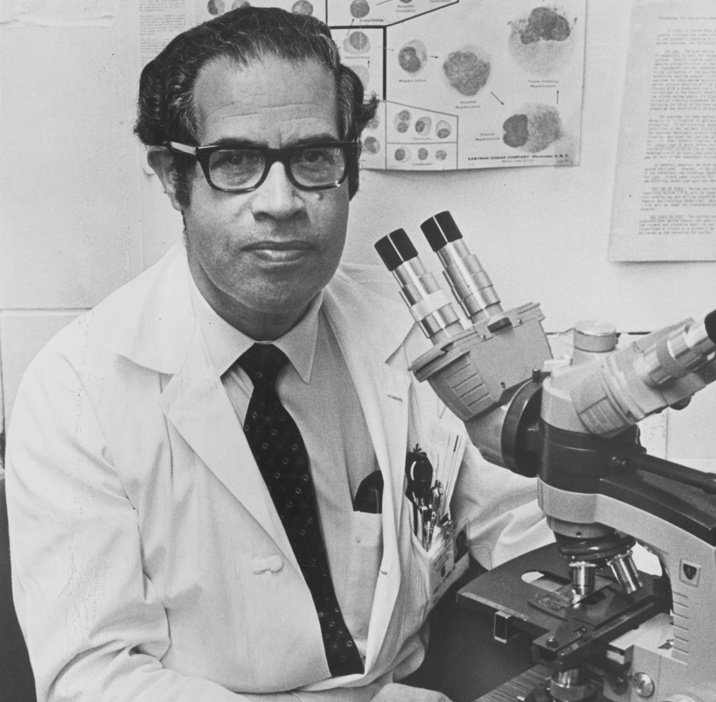

Podcast: Harold Freeman, father of patient navigation, on cutting the cancer out of Harlem

By Cancer History Project | Feb. 11, 2022

Harold Freeman had big plans after he finished his residency at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in 1968. He planned to cut cancer out of Harlem.

“I’m ready to do it. I’m skilled. I know how to cut cancer out. I want to cut it out of Harlem. I can’t do that. I can’t cut it out. It won’t yield. It won’t yield to the surgeon’s knife. It won’t yield to what we call the Bard-Parker, which was the name of the surgeon’s knife. Cancer wouldn’t yield,” Freeman said to The Cancer Letter in an interview with Robert A. Winn, director of VCU Massey Cancer Center, and John Stewart, founding director of LSU Health/LCMC Health Cancer Center. “Then I get to the reality, I can’t cut it out. Why? Because the people were coming in too late with cancer for me to be able to cut it out.”

Freeman made his career out of asking why it was that his patients, who were poor and Black, sought treatment too late. As president of the American Cancer Society in 1988-89, he published a study, “Cancer in the socioeconomically disadvantaged,” and made an unprecedented conclusion—“that the principal reason that Black people were dying from cancer was because they were poor.”

10

Panel: Odunsi, Pisters, Platanias, and Ulrich: How immigrating to the U.S. shaped their perspectives on oncology

By Cancer History Project | April 22, 2022

In a panel discussion this week, four cancer centers directors described how their experiences as immigrants have shaped their approach to oncology and the U.S. healthcare system.

The “International perspectives in U.S. cancer center leadership” panel, hosted by the Cancer History Project April 20, included:

- Narjust Duma, MD, moderator

Associate director, The Cancer Care Equity Program,

Thoracic oncologist, Lowe Center For Thoracic Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute,

Assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, - Kunle Odunsi, MD, PhD,

Director, University of Chicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center,

Dean for oncology, University of Chicago Biological Sciences Division,

AbbVie Foundation Distinguished Service Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology, - Peter WT Pisters, MD,

President, MD Anderson Cancer Center, - Leonidas Platanias, MD, PhD,

Director, Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University

Jesse, Sara, Andrew, Abigail, Benjamin and Elizabeth Lurie Professor of Oncology, Departments of Medicine and Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, - Cornelia Ulrich, PhD, MS,

Executive director, Comprehensive Cancer Center at Huntsman Cancer Institute,

Jon M. and Karen Huntsman Presidential Professor in Cancer Research,

Professor, Department of Population Health Sciences, University of Utah.

11

Sarah Cannon: The Name & The Story

By Sarah Cannon Research Institute | April 28, 2022

Sarah Cannon was the real name of the television and radio personality, Minnie Pearl. Sarah Cannon received treatment for breast cancer at the founding center in Nashville. Afterwards, she offered the use of her name to promote cancer research and patient education with a vision of offering patients convenient access to early detection, clinical trials, and a team approach to cancer care.

Since its inception in 1993, Sarah Cannon has taken many first steps in the fight against cancer, beginning with clinical research. With the focus of offering patients greater access to clinical trials at the earliest phases, Sarah Cannon’s founders established the first community-based cancer research program and, four years later, formed the first drug development program outside of an academic setting.

12

Podcast: Wayne Frederick on the legacy of LaSalle Leffall, Jr.

By Cancer History Project | Feb. 4, 2022

The Cancer History Project Guest Editor Robert Winn focused on the legacy of LaSalle Leffall, a Howard University surgical oncologist.

Winn is the director of VCU Massey Cancer Center. He and John H. Stewart, director of Louisiana State University-Louisiana Children’s Medical Center Health Cancer Center spoke with Wayne A.I. Frederick, president of Howard University.

Stewart and Frederick were mentored by Leffall.

Related:

- LaSalle D. Leffall, Jr., a pioneering surgeon, dies at 89, by Edith P. Mitchell, MD (The Cancer Letter, May 31, 2019)

13

Podcast: Dave Boule confronted polycythemia vera with an accountant’s consistency

By Cancer History Project | June 17, 2022

Soon after Dave Boule was diagnosed with polycythemia vera in 2006, he had a hunch that there were better treatment options out there.

“Not too long into my course of treatment with phlebotomy only, my platelets started to rise along with my red count, which is not unusual with the disease, and the doctor wanted to treat me with the anagrelide,” he said to Doroshow.

Boule did his research.

He had found studies by Richard T. Silver, professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, who is now director emeritus of the Richard T. Silver MD Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Center, and Jerry Le Pow Spivak, professor emeritus of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and director of the Center for the Chronic Myeloproliferative Disorders.

14

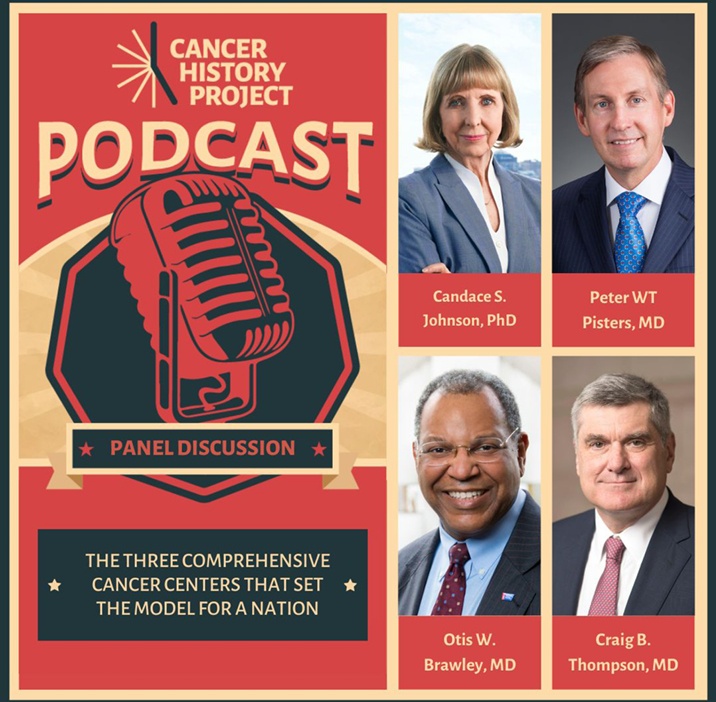

Panel: The three comprehensive cancer centers that set the model for a nation

By Cancer History Project | Aug. 6, 2021

Directors of the first three NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers are learning from the past, starting with the National Cancer Act, and mapping an equitable future for oncology.

On July 29, 2021, the Cancer History Project convened panelists Candace S. Johnson, president and CEO of Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Craig B. Thompson, president and CEO of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and Peter WT Pisters, president of MD Anderson Cancer Center, for a two hour Zoom session moderated by co-editor Otis W. Brawley.

Related:

- The history—and future—of oncology, according to directors of the first three NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers (The Cancer Letter, Aug. 6, 2021)

15

Podcast: In 1998, a CML patient was out of options. Then she chanced into a treatment–Gleevec

By Cancer History Project | June 3, 2022

When Judy Orem learned of her chronic myeloid leukemia diagnosis in 1995, she chose interferon over a treatment that seemed more risky—a bone marrow transplant.

“I don’t think I had any decision to make. I was simply told I was going to do that… It was that or nothing,” Orem said to Deborah Doroshow, assistant professor of medicine, hematology, and medical oncology at the Tisch Cancer Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who is guest editor of the Cancer History Project during the month of June.

Orem ruled out bone marrow transplantation from the outset. Doctors at Stanford told her that she would have a 50% chance of survival during her first year of that treatment. With interferon, she could get three to five years, she was told.

What did it take—and what did it mean—to survive with the disease and treatment at that time?

“We walked out of there, talked about it, and said, ‘You know? I’d rather spend the year feeling OK than to go through all that and 50% chance of dying from the treatment,’” she said. “And so I chose not to do anything other than the interferon.”

16

Panel: Knudsen, Hudis, Hughes-Halbert, Leader, Willman propose action plan on health equity

By Cancer History Project | May 13, 2022

In a panel discussion this week, five leaders in oncology proposed an action plan for tackling cancer health disparities and enhancing health equity.

The panel, “Health Equity: Advocacy and access,” hosted by the Cancer History Project May 9, 2022, included:

- Karen Knudsen, MBA, PhD,

CEO, American Cancer Society and the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, who moderated the event - Clifford A. Hudis, MD,

CEO, American Society of Clinical Oncology;

Executive vice chair, Conquer Cancer Foundation;

Chair, CancerLinQ - Chanita Hughes Halbert, PhD,

Vice chair for research, professor, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences;

Associate director for cancer equity, Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Southern California - Amy E. Leader, DrPH, MPH,

Associate professor of population science and medical oncology, associate director of community integration, Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center;

Public health teaching faculty, College of Population Health, Thomas Jefferson University - Cheryl Willman, MD,

Executive director, Mayo Clinic Cancer Programs (nationally and globally);

Director, Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center

17

Helen Coley Nauts: The Woman Who Resurrected Cancer Immunotherapy

By Cancer Research Institute | April 1, 2021

Helen Coley Nauts, the founder of the Cancer Research Institute (CRI), was a high school-educated housewife and mother who, from the time of her father’s death in 1936 until her own passing in 2001, would go on to fundamentally change the fields of cancer research and immunology.

Her determination and perseverance in the face of constant resistance from the medical establishment of her day laid the foundation for cancer immunotherapy as it is known today. For her contributions, Helen was named Commandeur de l’Ordre National du Merite by French president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing in 1981, and received the Gold Medal for “distinguished service to humanity” from The National Institute of Social Sciences in 1997—the first woman in the medical field to do so since the honor was bestowed upon Marie Curie in 1921.

18

The Story of City of Hope

By City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center | Feb. 23, 2021

In 1913, tuberculosis would kill nearly 150,000 people, more than twice the toll taken by cancer. A group of committed volunteers refused to accept this tragedy and established the Jewish Consumptive Relief Association (JCRA), a free, nonsectarian tuberculosis sanatorium.

After hosting several fundraisers, the JCRA placed a down payment on 10 acres of sun-soaked land in Duarte, California, where they would establish the Los Angeles Sanatorium a year later. The original sanatorium consisted of two canvas cottages and ultimately launched a century-long journey that would place City of Hope at the forefront of the nation’s leading medical and research institutions.

Their visionary efforts were rewarded when, by the mid-1940s, the discovery of antibiotics pushed tuberculosis into a decline across the United States. But there was no time for celebration. The pioneering thinkers at City of Hope had already trained their focus on humanity’s next great medical challenge: tackling the catastrophic disease of cancer. Later, they mounted a fight against diabetes and HIV/AIDS. In accepting each new medical challenge, however daunting, City of Hope continually reaffirms its humanitarian vision that “health is a human right.”

19

Paul Calabresi: A Founder and Giant in the Field of Medical Oncology

By Fred Schiffman, MD and Wafik El-Deiry, MD, PhD | May 12, 2021

The story of modern cancer therapy would not be complete without the inclusion of the work of Paul Calabresi and some insights about the challenges he faced, along with his accomplishments.

For this chapter in the “Cancer History Project”, I revised and extended a Memorial I wrote for Paul in 2006. I also had the pleasure of interviewing many who knew him well including his children: Steven Calabresi, Janice Calabresi Maggs, and Peter A. Calabresi, MD. Others gave generously of their time to speak with me and share stories and experiences which I hope will add some richness to Paul’s contributions as an oncologist.

They included Dr. Roy Herbst, Ensign Professor of Medicine (Medical Oncology), Professor of Pharmacology, Chief of Medical Oncology, Yale Cancer Center and Smilow Cancer Hospital and Associate Cancer Center Director, Translational Science, Dr. Edward Chu, Director of the National Cancer Institute-designated Albert Einstein Cancer Center, Vice President for Cancer Medicine at Montefiore Medicine, Professor of Medicine and of Molecular Pharmacology and Roger Einiger Professorship of Cancer Medicine at Einstein, Dr. Vincent DeVita, Amy and Joseph Perella Professor of Medicine at the Yale Cancer Center, Professor of Epidemiology and Public Health at Yale and Former Director of the Yale Cancer Center and Dr. Thomas DeNucci, Medical Director, Rhode Island Hospital Endoscopy, Gastroenterologist at Lifespan Physician Group and a Clinical Associate Professor of Medicine at The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

Paul Calabresi was born in Milan, Italy on April 5, 1930. He was the son of Dr. Massimo Calabresi and Bianca Maria Finzi-Contini Calabresi. In Europe, his family was active in the anti-fascist resistance but in 1939 fled to the United States.

Paul’s parents told the story of Paul’s arrival to America. He was literally the first one off the boat and ran down the gangway. He spread his arms wide and shouted, “I am an American boy now!” The family moved to New Haven where his father joined the faculty of Yale University School of Medicine as a cardiologist at the Veterans’ Administration Hospital. Paul’s mother was a scholar of European literature, earned a Ph.D. in French at Yale and was Professor of French and Italian at Connecticut College and for many years Professor and Chair of the Italian Department at Albertus Magnus College.

20

Dr. John Ultmann (1925-2000), a pioneer in the treatment of lymphoma

By University of Chicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center | July 14, 2022

John E. Ultmann, MD, (1925-2000) was an internationally recognized expert on the diagnosis, staging and treatment of Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma as well as on the development of cancer chemotherapy. He was a professor in the department of medicine and the founding director of the University of Chicago Cancer Research Center (now known as the University of Chicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center).

Ultmann was a pioneer in efforts to distinguish between the many different types of lymphomas. He was particularly well known for his work on precise staging of Hodgkin’s disease and the uses of staging as a guide for treatment.

“John Ultmann was an early proponent of the multi-disciplinary approach to treatment of lymphoma, which is associated with a tremendous improvement in the curability of the disease,” said Samuel Hellman, MD, the A.N. Pritzker Distinguished Service Professor in the department of radiation and cellular oncology and former dean of the biological sciences at the University. “He was known within the University as an outstanding teacher who trained many of the current leaders in the field, as a key player in assembling the world-renowned medical oncology group here, and as a compassionate physician who took excellent care of his patients until just a few weeks before his own death.”

21

Duke Celebrates 50 Years of Cancer Care — and Looks Toward the Next 50

By Duke Cancer Institute | July 7, 2022

When Joseph O. Moore, MD, came to Duke as a fellow in 1975, he and his mentors treated chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) with a chemotherapy regimen that was like a “wet blanket.” It suppressed the cancer for a few years. “But it didn’t change the trajectory of the disease,” Moore said. Patients developed acute leukemia, which was almost always fatal.

By the early 1990s, younger patients could achieve a cure with a bone marrow transplant, though complications were common. By 1999, Moore was the Duke investigator for a national study of a targeted drug, imatinib, which stops leukemia cells from growing by shutting down a key protein. When imatinib was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2001, it transformed CML into a disease easily treated by taking a pill.

When Moore retired from clinical practice in 2019, he was involved in a study following people with CML who had been taking imatinib long term, which showed they could safely stop therapy.

22

Gone Too Soon: Dr. Neil Spector Passes Away (1956-2020)

By Duke Cancer Institute | April 15, 2022

Flags were lowered to half-staff today (June 17, 2020) across Duke for Neil Spector, MD, a nationally recognized physician-scientist, translational research leader, and oncology mentor, who passed away on Sunday, June 14, 2020. He was 63.

Dr. Spector was the Sandra Coates Associate Professor in the Department of Medicine, an associate Professor of Pharmacology and Cancer Biology, and a member of the Duke Cancer Institute.

He joined Duke Cancer Institute and the faculty at Duke University School of Medicine in September 2006 after serving for eight years as director of Exploratory Medical Sciences-Oncology at GlaxoSmithKline and as adjunct associate professor of Medicine, Division of Hematology/Oncology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dr. Spector’s appointments at DCI include having served as associate director for Translational Research, director of the Developmental Therapeutics Program, and associate co-director of Clinical Research with the Breast Cancer disease group.

His laboratory research focused on elucidating molecular mechanisms of therapeutic resistance to targeted therapies and strategies to prevent and overcome resistance. He is credited with leading two molecularly targeted therapies to FDA approval, one for the treatment of pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (nelarabine) and another for the treatment of HER2 overexpressing breast cancers (lapatinib).

A medical oncologist, Dr. Spector most recently served as an attending physician and supervised medical oncology fellows at the Durham VA Healthcare System.

23

Carol Fabian on breast cancer prevention and tissue sampling using fine needle aspiration

By Cancer History Project | March 25, 2022

Carol Fabian recalls the emotional hardship that came with treating women for breast cancer in the 1970s and eighties.

“This was prior to adjuvant trastuzumab, and despite aggressive cytotoxic adjuvant treatment, too many of these young women relapsed and died,” said Carol Fabian, director of the Breast Cancer Prevention and Survivorship Research Center, holder of the Medical Oncology Mark and Bette Morris Family Professorship in Cancer Prevention, Mark and Bette Morris Foundation, and University Distinguished Professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

“These women often had young children and/or were at the height of their careers,” Fabian said to The Cancer Letter. “This was a tragedy over, and over, and over again. It was becoming emotionally very difficult to handle.”

Fabian’s husband recognized the toll this took on her, and suggested another field of medicine.

“I did not want to give up oncology, but for balance wanted to switch to a research focus, with a little more light at the end of the tunnel. That research focus was cancer prevention,” Fabian said.

While Fabian still treated breast cancer patients, she pivoted to prevention work and developed a minimally invasive technique to collect healthy breast tissue in women called fine needle aspiration.

24

How Utah’s Unique Resources Spearheaded Cancer Genetic Discoveries at Huntsman Cancer Institute

By Huntsman Cancer Institute | Feb. 17, 2022

Utah is a veritable wellspring of genetic discoveries. Researchers at the University of Utah (U of U) can claim the discovery of 50 genes involved in inherited disease risk.

The foundation of that wellspring was a singular resource: an abundance of detailed family trees. But it took the foresight of several Utah researchers to understand the potential of this data and determine how to harness its power for genetic discovery.

This focus on a genetic approach to understanding disease came to the attention of Jon M. and Karen Huntsman. Jon Huntsman lost his mother to cancer. After his own experience with the disease, he and Karen became committed to the cancer cause. When they learned of the genetics work occurring at the U of U—in their own backyard—they felt their financial support would have the greatest impact there.

In 1995, the Huntsman family made a major gift that enabled the establishment of a state-of-the-art research, education, and cancer care facility on the U of U campus, becoming critical investors in the cancer genetics work that has had a significant impact across the world. Today, Huntsman Cancer Institute has grown into more than one million square feet of research and clinical space.

25

Podcast: Tim Wendel on the “Cancer Cowboys” and getting to know the ALGB

By Cancer History Project | March 18, 2022

A band of “Cancer Cowboys” once known as the ALGB—Acute Leukemia Group B—are, in large part, responsible for flipping the mortality rate of childhood leukemia from 90% to 10%, where it stands today.

“The Cancer Cowboys arguably better utilized many of the newer meds becoming available—6-MP, methotrexate, daunomycin, Cytoxan,” Tim Wendel, member of the Cancer History Project editorial board, lecturer at Johns Hopkins University, and author of “Cancer Crossings: A Brother, His Doctors, and the Quest for a Cure to Childhood Leukemia,” said to The Cancer Letter. “Most of the old guard…were giving them to the patients one at a time. What the ALGB group did was, ‘Screw this. We don’t have time. We’re going to do it in combination two, three, even four at a time.’”

While researching his book from 2013 to 2017, Wendel spoke with the doctors of ALGB, among them longtime St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital CEO Donald Pinkel, who died March 9, Jerry Yates, Lucius Sinks, James and Jimmie Holland, Emil “Tom” Frei, and Emil J Freireich. Wendel’s brother Eric was treated at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center beginning when he was diagnosed in 1966, until he died in 1973.

Related:

- The Donald Pinkel Archive

- Donald Pinkel, St. Jude founding medical director who brought the word “cure” to cancer, dies at 95, by Tim Wendel, March 18, 2022

- Reflecting on Donald Pinkel’s legacy as a physician, scientist, and humanitarian, by Mary Pinkel, March 18, 2022

- Children First: Dr. Donald Pinkel and the Quest to Cure Childhood Leukemia, by Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, March 16, 2022

- St. Jude’s founding medical director Donald Pinkel set the scientific trajectory for curing childhood cancer, by St. Jude, March 17, 2022