In the 1970s, when E. Donnall Thomas was researching bone marrow transplantation, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center started a database of transplant recipients.

Now, this database has led to new findings.

“We are fortunate at Fred Hutch to have a very robust long-term follow-up program for transplant recipients,” said Masumi Ueda Oshima, associate professor in Fred Hutch’s Clinical Research Division.

“So, we have contact information for people who were transplanted at Fred Hutch as far back as the 1970s. We reached out to survivors from this list about participating in the study and asked if it would also be OK to contact their donors.”

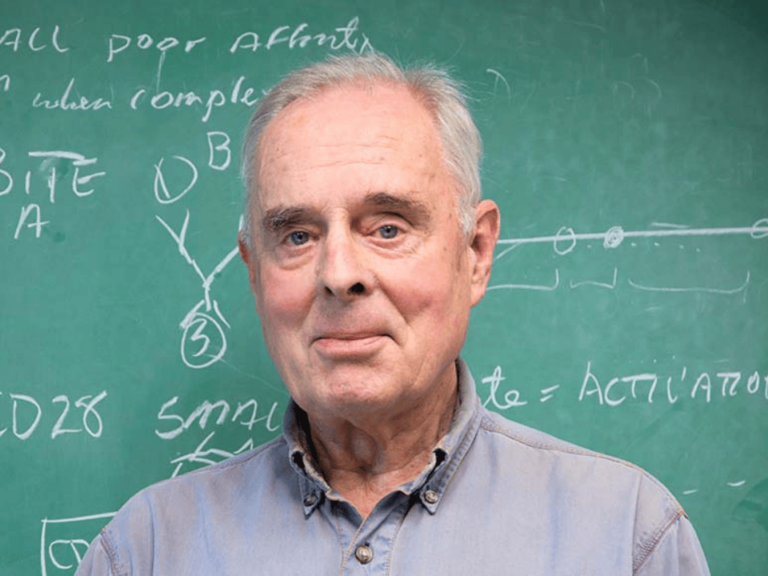

Thomas won a Nobel Prize for his work in 1990. He died Oct. 20, 2012, at age 92.

How a database stretching back to the 1970s leads to new findings about blood cell mutations

By Fred Hutch, April 11, 2025

After an allogeneic stem cell transplant, a recipient’s body faces a daunting task: rebuilding the person’s blood-forming and immune systems from the ground up from a relatively small number of “seed” cells obtained from their donor.

To achieve this, the donated cells must replicate again and again — and again.

In this Q&A, lead author Masumi Ueda Oshima, MD, MA, explains the study and its implications.

Video: Retired oncology nurses reflect on a career as Don Thomas’s “secret weapons”

By Fred Hutch, April 10, 2025

They call themselves the “Regals and Reguys” — a group of retired Fred Hutch nurses who dedicated decades of their lives to patient care, advancing clinical research and refining cancer treatments that have saved thousands of lives. Through years of triumphs, challenges and shared experiences, they formed lasting friendships that have withstood the test of time.

In a video from a recent reunion, Dorothy Ghaly, an RN retired from Fred Hutch, explained their work in clinical medicine.

Early leaders and innovators at Fred Hutch

By Fred Hutch, April 10, 2025

In 1975 Fred Hutch opened its doors as one of the first of eight new comprehensive centers authorized by the 1971 National Cancer Act. Founded by Seattle oncologist and surgeon Dr. Bill Hutchinson, he named it in honor of his younger brother, Fred Hutchinson. Fred was a Major League Baseball pitcher and manager who died of cancer in 1964 at the age of 45.

Without a massive endowment or a hospital to call his own, Dr. Hutchinson assembled a team of doctors and scientists to accomplish three missions:

- Investigate the fundamental biology of cancer,

- Study the spread, control and prevention of disease, and

- Achieve a cure for leukemia and other blood diseases through bone marrow transplantation.

Despite setbacks along the way, the small but mighty team that started Fred Hutch persisted, establishing a cure for blood diseases that continues to save the lives of thousands of patients around the world and launching a new era of medicine that seeks to harness the power of the human immune system.

More articles about bone marrow transplantation

Chris Lundy had one week to live; 52 years later, he is the longest living BMT recipient at the Hutch

By Cancer History Project, Sept. 15, 2023

At 75, Chris Lundy is one of the longest living recipients of a bone marrow transplant.

He was among the patients included in the 1975 paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine titled “Bone-Marrow Transplantation.”

“It was a paper everyone interested in bone marrow transplantation read word for word,” Frederick Appelbaum, executive vice president, professor in the Clinical Research Division, and Metcalfe Family/Frederick Appelbaum Endowed Chair in Cancer Research at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, wrote in his book “Living Medicine.” “It was the article that introduced marrow transplantation to the general medical community.”

Lundy’s path to diagnosis and treatment was not simple. At age 18, during basic training in Fort Polk, LA, Lundy slipped and broke his wrist.

At the hospital, the doctors set his wrist and ran some blood tests. What Lundy thought would be a simple visit turned into an eight-month stay.

“What they found was that I had an extremely low hematocrit,” Lundy said to Deborah Doroshow, assistant professor of medicine, hematology, and medical oncology at the Tisch Cancer Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “I was jaundiced, I had double walking pneumonia, and I was a pretty sick puppy. And if I hadn’t broken my wrist and gone to the hospital, I probably wouldn’t have been around too much longer—because I think my hematocrit was about four and a half or five, and normal was supposed to be up around 15.”

In 1970, in the journal Blood, a second-year medical student named Frederick Appelbaum read a paper describing a 46-year-old man with blastic crisis of chronic myelogenous leukemia who was given 950 rads whole-body irradiation followed immediately by 17.6 x 109 marrow cells.

To rescue this patient from this lethal dose, the study’s senior author—E. Donnall Thomas—injected marrow cells from the patient’s sister into the patient, and the cells successfully grafted.

The concept, blood marrow transplantation, was considered new, strange, and imperfect. Appelbaum, then a student at Tufts, felt the unmistakable recognition of his own path in the world.

“Why does somebody love classical music or someone love poetry? There are things that just appeal to us,” said Appelbaum, executive vice president, professor in the Clinical Research Division, and Metcalfe Family/Frederick Appelbaum Endowed Chair in Cancer Research at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center. “[Bone marrow transplantation] hadn’t been worked out in humans yet. But the idea that you could get rid of someone’s entire hematopoietic system and transplant a normal one in place of it just seemed extraordinary.

“From then on, don’t ask me why, it was like having my brain tattooed. I just couldn’t get it out of my mind,” he said.

Delving deep into Thomas’s role in discovering bone marrow transplantation and its role in curing hematologic cancers, Appelbaum, who became Thomas’s mentee and collaborator, wrote “Living Medicine: Don Thomas, Marrow Transplantation, and the Cell Therapy Revolution.”

Dorothy “Dottie” Thomas, 92, “Mother of Bone Marrow Transplantation”

Dorothy “Dottie” Thomas, wife and research partner to 1990 Nobel laureate E. Donnall Thomas, died Jan. 9, at her home near Seattle. She was 92.

Don Thomas, pioneer of the bone marrow transplant and former director of the Clinical Research Division at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, preceded her in death on Oct. 20, 2012, also at age 92.

The Thomases formed the core of a team that proved bone marrow transplantation could cure leukemias and other blood cancers, work that spanned several decades.

“Dottie’s life had a profound impact, not just on those who knew her personally, but also countless patients,” said Fred Hutch President and Director Gary Gilliland, who became friends with the Thomases when he and Don served on the advisory board of the José Carreras Leukaemia Foundation.

Dottie Thomas, known as “the mother of bone marrow transplantation,” may have gotten the name from the late George Santos, a bone marrow transplantation expert at Johns Hopkins University and a professional colleague. “If Dr. Thomas is the father of bone-marrow transplantation, then Dottie Thomas is the mother,” he once said

How George Santos and Al Owens’s early Cytoxan studies led to standard-of-care therapy in BMT

By Cancer History Project, Nov. 10, 2023

George Santos, founder of Johns Hopkins University Bone Marrow Transplantation Program, pioneered many of the innovations used in bone marrow transplantation that are relevant today—but he didn’t get nearly as much credit as others working in the field.

E. Donnall Thomas, another early pioneer of bone marrow transplantation who conducted research out of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, shared the 1990 Nobel Prize in Medicine with Joseph E. Murray “for their discoveries concerning organ and cell transplantation in the treatment of human disease.”

“Much of what we’re currently doing in bone marrow transplant internationally was developed by George,” Richard J. Jones, professor of oncology and medicine, director of the Bone Marrow Transplantation Program, and co-director, Hematologic Malignancies Program, at The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, said on the Cancer History Project podcast.

Letter to the editor: Hopkins’s George Santos is a pioneer of bone marrow transplantation

After reading last week’s coverage of Fred Appelbaum’s “Living Medicine: Don Thomas, Marrow Transplantation, and the Cell Therapy Revolution,” Jerome Yates, emeritus professor of oncology at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer, wrote a letter to the editor addressing the contributions of another leader in the field of bone marrow transplantation—George Santos.

Yates: As I read the recent issue of The Cancer Letter, I could not help but reflect on the environment around bone marrow transplantation in the early 1970s.

Don Thomas got much of the credit, but the other major leader in the field was George Santos—who was at Johns Hopkins. Don Thomas introduced the use of the radiation to ablate the leukemic bone marrow as the preparative regimen, but it was George Santos who introduced the use of high dose cyclophosphamide as a preparative regimen that did not require the two headed cobalt unit that Thomas had at the Mary Imogene Bassett hospital in Cooperstown.

I had them both to Roswell in about 1970 to critique our program—and both were pioneers. Thomas got the Nobel prize because of the volume and innovation, but in many ways, Santos did as much for the advancement of the therapeutic technique.

Dr. George Santos on Bone Marrow Transplantation for Cancer Today, 1989

By Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, May 19. 2021

Dr. George Santos on Bone Marrow Transplantation for Cancer Today. Originally published in 1989.

“We have been using family members for donors of bone marrow; unfortunately, however, donors are not available for most patients. We are now trying another approach, that of using the patient’s own bone marrow, first purging it of any tumor cells. With this approach in acute myelogenous leukemia, we have done relatively well in patients in second and third remissions, achieving a 30% disease-free survival in over 60 patients.”

This column features the latest posts to the Cancer History Project by our growing list of contributors.

The Cancer History Project is a free, web-based, collaborative resource intended to mark the 50th anniversary of the National Cancer Act and designed to continue in perpetuity. The objective is to assemble a robust collection of historical documents and make them freely available.

Access to the Cancer History Project is open to the public at CancerHistoryProject.com. You can also follow us on Twitter at @CancerHistProj, or follow our podcast.

Is your institution a contributor to the Cancer History Project? Eligible institutions include cancer centers, advocacy groups, professional societies, pharmaceutical companies, and key organizations in oncology.

To apply to become a contributor, please contact admin@cancerhistoryproject.com.